Liquid Conservation in Orangutans (Pongo Pygmaeus) and Humans (Homo Sapiens): Individual Differences and Perceptual Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Koko

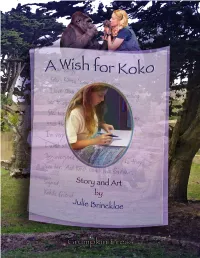

1 A Wish for Koko by Julie Brinckloe 2 This book was created as a gift to the Gorilla Foundation. 100% of the proceeds will go directly to the Foundation to help all the Kokos of the World. Copyright © by Julie Brinckloe 2019 Grumpkin Press All rights reserved. Photographs and likenesses of Koko, Penny and Michael © by Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation Koko’s Kitten © by Penny Patterson, Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation No part of this book may be used or reproduced in whole or in part without prior written consent of Julie Brinckloe and the Gorilla Foundation. Library of Congress U.S. Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 2-131-759 ISBN 978-0-578-51838-1 Printed in the U.S.A. 0 Thank You This story needed inspired players to give it authenticity. I found them at La Honda Elementary School, a stone’s throw from where Koko lived her extraordinary life. And I found it in the spirited souls of Stella Machado and her family. Principal Liz Morgan and teacher Brett Miller embraced Koko with open hearts, and the generous consent of parents paved the way for students to participate in the story. Ms. Miller’s classroom was the creative, warm place I had envisioned. And her fourth and fifth grade students were the kids I’d crossed my fingers for. They lit up the story with exuberance, inspired by true affection for Koko and her friends. I thank them all. And following the story they shall all be named. I thank the San Francisco Zoo for permission to use my photographs taken at the Gorilla Preserve in this book. -

Chimpanzees Use of Sign Language

Chimpanzees’ Use of Sign Language* ROGER S. FOUTS & DEBORAH H. FOUTS Washoe was cross-fostered by humans.1 She was raised as if she were a deaf human child and so acquired the signs of American Sign Language. Her surrogate human family had been the only people she had really known. She had met other humans who occasionally visited and often seen unfamiliar people over the garden fence or going by in cars on the busy residential street that ran next to her home. She never had a pet but she had seen dogs at a distance and did not appear to like them. While on car journeys she would hang out of the window and bang on the car door if she saw one. Dogs were obviously not part of 'our group'; they were different and therefore not to be trusted. Cats fared no better. The occasional cat that might dare to use her back garden as a shortcut was summarily chased out. Bugs were not favourites either. They were to be avoided or, if that was impossible, quickly flicked away. Washoe had accepted the notion of human superiority very readily - almost too readily. Being superior has a very heady quality about it. When Washoe was five she left most of her human companions behind and moved to a primate institute in Oklahoma. The facility housed about twenty-five chimpanzees, and this was where Washoe was to meet her first chimpanzee: imagine never meeting a member of your own species until you were five. After a plane flight Washoe arrived in a sedated state at her new home. -

Menagerie to Me / My Neighbor Be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900

“MENAGERIE TO ME / MY NEIGHBOR BE”: EXOTIC ANIMALS AND AMERICAN CONSCIENCE, 1840-1900 Leslie Jane McAbee A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Eliza Richards Timothy Marr Matthew Taylor Ruth Salvaggio Jane Thrailkill © 2018 Leslie Jane McAbee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Leslie McAbee: “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900 (Under the direction of Eliza Richards) Throughout the nineteenth century, large numbers of living “exotic” animals—elephants, lions, and tigers—circulated throughout the U.S. in traveling menageries, circuses, and later zoos as staples of popular entertainment and natural history education. In “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be,” I study literary representations of these displaced and sensationalized animals, offering a new contribution to Americanist animal studies in literary scholarship, which has largely attended to the cultural impact of domesticated and native creatures. The field has not yet adequately addressed the influence that representations of foreign animals had on socio-cultural discourses, such as domesticity, social reform, and white supremacy. I examine how writers enlist exoticized animals to variously advance and disrupt the human-centered foundations of hierarchical thinking that underpinned nineteenth-century tenets of civilization, particularly the belief that Western culture acts as a progressive force in a comparatively barbaric world. Both well studied and lesser-known authors, however, find “exotic” animal figures to be wily for two seemingly contradictory reasons. -

Ndume, and Hayes, J.J

Publications Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Hayes, J.J. (2003) Castration as a Viable Alternative to Zeta Male Propagation. J. Primate Behavior [in press]. Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Hayes, J.J. (2003) Identification of POZM-A Novel Protease That is Essential for Degradation of Zeta-Male Protein. Nature [in press]. Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Gorilla, T.T. (2001) A Critical Review of the Color Pink and Anger Management. J. Primate Behavior, 46: 8012-8021. Ndume, and Gorilla, T.T. (2001) Escalation of Dominance and Aberrant Behavior of Alpha-Males in the Presence of Alpha-Females. J. Primate Behavior, 45: 7384-7390. Ndume, Koko, Gorilla, T.T. (2001) The ëPound Head with Fistí is the Preferred Method of Establishment of Dominance by Alpha- males in Gorilla Society. J. Primate. Behavior, 33: 3753-3762. Graueri, G., Ndume, and Gorilla, E.P. (1996) Rate of Loss of Banana Peel Pigmentation after Banana Consumption. Anal. Chem., 42: 1570-85. Education Ph.D. in Behavioral Biology, Gorilla Foundation 2000 Cincinnati, OH. M.S. in Behavioral Etiquette 1998 Sponge Bob University for Primate Temperament Training. *Discharged from program for non-compliance. Ph.D. in Chemistry 1997 Silverback University, Zaire B.S. in Survival and Chemical Synthesis ? - 1995 The Jungle, Zaire Research Experience Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 2001 - Present Postdoctoral Fellow Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey J. Hayes Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 2000 - 2001 Postdoctoral Fellow Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey J. Hayes Department of Behavioral Biology, Gorilla Foundation, Cincinnati OH 1997 - 2000 Ph.D. -

Pre-Sleep and Sleeping Platform Construction Behavior in Captive Orangutans (Pongo Spp

Original Article Folia Primatol 2015;86:187–202 Received: July 28, 2014 DOI: 10.1159/000381056 Accepted after revision: February 18, 2015 Published online: May 13, 2015 Pre-Sleep and Sleeping Platform Construction Behavior in Captive Orangutans (Pongo spp. ): Implications for Ape Health and Welfare a b–d David R. Samson Rob Shumaker a b Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, N.C., Indianapolis c Zoo, VP of Conservation and Life Sciences, Indianapolis, Ind. , Indiana University, d Bloomington, Ind. , and Krasnow Institute at George Mason University, Fairfax, Va. , USA Key Words Orangutan · Sleep · Sleeping platform · Nest · Animal welfare · Ethology Abstract The nightly construction of a ‘nest’ or sleeping platform is a behavior that has been observed in every wild great ape population studied, yet in captivity, few analyses have been performed on sleep related behavior. Here, we report on such behavior in three female and two male captive orangutans (Pongo spp.), in a natural light setting, at the Indianapolis Zoo. Behavioral samples were generated, using infrared cameras for a total of 47 nights (136.25 h), in summer (n = 25) and winter (n = 22) periods. To characterize sleep behaviors, we used all-occurrence sampling to generate platform construction episodes (n = 217). Orangutans used a total of 2.4 (SD = 1.2) techniques and 7.5 (SD = 6.3) actions to construct a sleeping platform; they spent 10.1 min (SD – 9.9 min) making the platform and showed a 77% preference for ground (vs. elevated) sleep sites. Com- parisons between summer and winter platform construction showed winter start times (17:12 h) to be significantly earlier and longer in duration than summer start times (17:56 h). -

Animal Thoughts on Factory Farms: Michael Leahy, Language and Awareness of Death

BETWEEN THE SPECIES Issue VIII August 2008 www.cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ Animal Thoughts on Factory Farms: Michael Leahy, Language and Awareness of Death Rebekah Humphreys Email: [email protected] Cardiff University of Wales, Cardiff, United Kingdom Abstract The idea that language is necessary for thought and emotion is a dominant one in philosophy. Animals have taken the brunt of this idea, since it is widely held that language is exclusively human. Michael Leahy (1991) makes a case against the moral standing of factory-farmed animals based on such ideas. His approach is Wittgensteinian: understanding is a thought process that requires language, which animals do not possess. But he goes further than this and argues that certain factory farming methods do not cause certain sufferings to the animals used, since animals lack full awareness of their circumstances. In particular he argues that animals do not experience certain sufferings at the slaughterhouse since, lacking language, they are unaware of their fate (1991). Through an analysis of Leahy’s claims this paper aims to explore and challenge both the idea that thought and emotion require language and that only humans possess language. Between the Species, VIII, August 2008, cla.calpoly.edu/bts/ 1 Awareness of Death While the evidence of animal suffering in factory farming is extensive and it is generally held that animals are sentient, some philosophers, such as Michael Leahy (1991), claim that animals either do not suffer through certain factory farming methods and conditions or that the practice poses no moral issues, or both. In light of the evidence of animal suffering and sentience, on what basis are such claims made? Leahy argues that animals do not experience certain sufferings on the way to the slaughterhouse, and also do not experience certain sufferings when, at the slaughterhouse, animals are killed in full view of other animals. -

The Case for the Personhood of the Gorillas

The Case for the Personhood of Gorillas* FRANCINE PATTERSON & WENDY GORDON We present this individual for your consideration: She communicates in sign language, using a vocabulary of over 1,000 words. She also understands spoken English, and often carries on 'bilingual' conversations, responding in sign to questions asked in English. She is learning the letters of the alphabet, and can read some printed words, including her own name. She has achieved scores between 85 and 95 on the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test. She demonstrates a clear self-awareness by engaging in self-directed behaviours in front of a mirror, such as making faces or examining her teeth, and by her appropriate use of self- descriptive language. She lies to avoid the consequences of her own misbehaviour, and anticipates others' responses to her actions. She engages in imaginary play, both alone and with others. She has produced paintings and drawings which are representational. She remembers and can talk about past events in her life. She understands and has used appropriately time- related words like 'before', 'after', 'later', and 'yesterday'. She laughs at her own jokes and those of others. She cries when hurt or left alone, screams when frightened or angered. She talks about her feelings, using words like 'happy', 'sad', 'afraid', 'enjoy', 'eager', 'frustrate', 'mad' and, quite frequently, 'love'. She grieves for those she has lost- a favourite cat who has died, a friend who has gone away. She can talk about what happens when one dies, but she becomes fidgety and uncomfortable when asked to discuss her own death or the death of her companions. -

4 a Complex-Adaptive-Systems Approach to the Evolution of Language and the Brain

- 4 A Complex-Adaptive-Systems Approach to the Evolution of Language and the Brain P Thomas Schoenemann 1 Introduction Language has arguably been as important to our species' evolutionary success as has any other behavior. Understanding how language evolved is therefore one of the most interesting questions in evolutionary biology. Part of this story involves understanding the evolutionary changes in our biology, particularly our brain. However, these changes cannot themselves be understood indepen dent of the behavioral effectsthey made possible. The complexity of our inner mental world - what will here be referred to as conceptual complexity- is one critical result of the evolution of our brain, and it will be argued that this has in turn led to the evolution oflanguage structure via cultural mechanisms (many of which remain opaque and hidden fromour conscious awareness). From this per spective, the complexity oflanguage is the result of the evolution ofcomplexity in brain circuits underlying our conceptual awareness. However, because indi vidual brains mature in the context of an intensely interactive social existence - one that is typical of primates generally but is taken to an unprecedented level among modern humans - cultural evolution of language has itself contributed to a richer conceptual world. This in turn has produced evolutionary pressures to enhance brain circuits primed to learn such complexity. The dynamics oflan guage evolution, involving brain/behavior co-evolution in this way, make it a prime example of what have been called "complex adaptive systems" (Beckner et al. 2009). Complex adaptive systems are phenomena that result fromthe interaction of many individual components as they adapt and learn fromeach other (Holland 2006). -

Language and the Orang-Utan: the Old 'Person' of the Forest*

Language and the Orang-utan: The Old 'Person' of the Forest* H. LYN WHITE MILES I still maintain, that his [the orang-utan] being possessed of the capacity of acquiring it [language], by having both the human intelligence and the organs of pronunciation, joined to the dispositions and affections of his mind, mild, gentle, and humane, is sufficient to denominate him a man. Lord J. B. Monboddo, Of the Origin and Progress of Language, 17731 If we base personhood on linguistic and mental ability, we should now ask, 'Are orang-utans or other creatures persons?' The issues this question raises are complex, but certainly arrogance and ignorance have played a role in our reluctance to recognise the intellectual capacity of our closest biological relatives - the nonhuman great apes. We have set ourselves apart from other animals, because of the scope of our mental abilities and cultural achievements. Although there were religious perspectives that did not emphasise our estrangement from nature, such as the doctrine of St. Francis and forms of nature religions, the dominant Judeo-Christian tradition held that white 'man' was separate and was given dominion over the earth, including other races, women, children and animals. Western philosophy continued this imperious attitude with the views of Descartes, who proposed that animals were just like machines with no significant language, feelings or thoughts. Personhood was denied even to some human groups enslaved by Euro-American colonial institutions. Only a century or so ago, scholarly opinion held that the speech of savages was inferior to the languages of complex societies. While nineteenth-century anthropologists arrogantly concerned themselves with measurements of human skulls to determine racial superiority, there was not much sympathy for the notion that animals might also be persons. -

And Chimpanzees (P

eScholarship International Journal of Comparative Psychology Title Monitoring Spatial Transpositions by Bonobos (Pan paniscus) and Chimpanzees (P. troglodytes) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5099j6v4 Journal International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 13(1) ISSN 0889-3675 Authors Beran, Michael J. Minahan, Mary F. Publication Date 2000 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California - 1 - International Journal of Comparative Psychology, 2000, 13, 1-15. Copyright 2000 by the International Society for Comparative Psychology Monitoring Spatial Transpositions by Bonobos (Pan paniscus) and Chimpanzees (P. troglodytes) Michael J. Beran and Mary F. Minahan Georgia State University, U.S.A. Two bonobos (Pan paniscus) and three chimpanzees (P. troglodytes) monitored spatial transpositions, or the simultaneous movement of multiple items in an array, so as to select a specific item from the array. In the initial condition of Experiment 1, food reward was hidden beneath one of four cups, and the apes were required to select the cup containing the reward in order to receive it. In the second condition, the test board on which the cups were located was rotated 180 degrees after placement of the food reward. In the third condition, two of the three cups switched locations with one another after placement of the food reward. All five apes performed at very high levels for these conditions. Ex- periment 2 was a computerized simulation of the tasks with the cups in which the apes had to track one of four simultaneously moving stimuli on a computer monitor. -

Koko Communicates

LESSON 11 TEACHER’S GUIDE Koko Communicates by Justin Marciniak Fountas-Pinnell Level O Narrative Nonfiction Selection Summary Koko the gorilla was taught to “speak” an astonishing 1,000-plus words in sign language by Penny, her human caregiver. Koko signs her thoughts, feelings, and even made-up insults. She has two gorilla friends who also sign, and a kitten she named “Smoke.” Number of Words: 822 Characteristics of the Text Genre • Narrative nonfi ction Text Structure • Third-person narrative in fi ve chronological sections Content • Koko and gorilla behavior; teaching Koko sign language • American Sign Language • Koko’s life and her human and animal companions Themes and Ideas • Animals and people can learn from each other. • Animals can think, feel, communicate, invent, and learn. • Animals and their human caregivers develop close bonds. Language and • Informal narrative between gorillas Literary Features • Narrative presents most information in chronological fashion Sentence Complexity • Mix of complex sentences and simple sentences • Items in a series • Words in quotation marks, dashes, italics, parentheses Vocabulary • Words and phrases associated with zoos and biologists: western lowland gorilla, biological, assistants, researchers Words • Multisyllable words, such as communicates, university, disciplined, biological • Hyphenated words, such as one-year-old, three-year-old, hide-and-seek, reddish-orange Illustrations • Photographs with captions, charts, sidebars Book and Print Features • Twelve pages of text, most with illustrations -

Animal Communication & Language

9781446295649_C.indd 6 14/06/2017 17:18 00_CARPENDALE ET AL_FM.indd 3 11/14/2017 4:45:07 PM Animal Communication and Human 7 Language LEARNING OUTCOMES By the end of this chapter you should: • Understand how the study of animal communication informs us about the nature and sophistication of human communication. • Be able to discuss the details of the communication patterns of vervet monkeys and honeybees. • Know that attempts to teach apes to speak have been conducted for a hundred years and why those based on behavioural training were inconclusive. • Be able to define what a LAD and a LASS are (and know their theoretical differences). • Be able to discuss the differences between human and animal communication and therefore the complexity of the latter. • Be aware of how more recent training programmes based on social interaction have changed our understanding of how apes may learn to communicate with humans as well as how they have informed our understanding of children’s early language development. Do animals use languages? Can dogs learn words? Rico, a 9-year-old border collie, was able to learn 200 words (Kaminski, Call, & Fischer, 2004). But are these really words in the same sense that humans use them? What Rico had learned was to fetch 200 different 07_CARPENDALE ET AL_CH_07.indd 121 11/14/2017 10:48:26 AM 122 THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHILDREN’S THINKING objects (Bloom, 2004). This is an incredibly impressive feat, but what does it tell us about human languages? When a child learns a word, more is expected than the ability to fetch the object that it identifies.