Animal Thoughts on Factory Farms: Michael Leahy, Language and Awareness of Death

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Koko

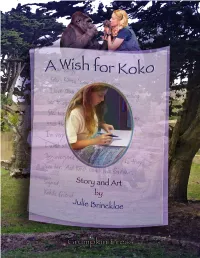

1 A Wish for Koko by Julie Brinckloe 2 This book was created as a gift to the Gorilla Foundation. 100% of the proceeds will go directly to the Foundation to help all the Kokos of the World. Copyright © by Julie Brinckloe 2019 Grumpkin Press All rights reserved. Photographs and likenesses of Koko, Penny and Michael © by Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation Koko’s Kitten © by Penny Patterson, Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation No part of this book may be used or reproduced in whole or in part without prior written consent of Julie Brinckloe and the Gorilla Foundation. Library of Congress U.S. Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 2-131-759 ISBN 978-0-578-51838-1 Printed in the U.S.A. 0 Thank You This story needed inspired players to give it authenticity. I found them at La Honda Elementary School, a stone’s throw from where Koko lived her extraordinary life. And I found it in the spirited souls of Stella Machado and her family. Principal Liz Morgan and teacher Brett Miller embraced Koko with open hearts, and the generous consent of parents paved the way for students to participate in the story. Ms. Miller’s classroom was the creative, warm place I had envisioned. And her fourth and fifth grade students were the kids I’d crossed my fingers for. They lit up the story with exuberance, inspired by true affection for Koko and her friends. I thank them all. And following the story they shall all be named. I thank the San Francisco Zoo for permission to use my photographs taken at the Gorilla Preserve in this book. -

Hypatia of Alexandria A. W. Richeson National Mathematics Magazine

Hypatia of Alexandria A. W. Richeson National Mathematics Magazine, Vol. 15, No. 2. (Nov., 1940), pp. 74-82. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=1539-5588%28194011%2915%3A2%3C74%3AHOA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-I National Mathematics Magazine is currently published by Mathematical Association of America. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/maa.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sun Nov 18 09:31:52 2007 Hgmdnism &,d History of Mdtbenzdtics Edited by G. -

Reason and Necessity: the Descent of the Philosopher Kings

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Philosophy Faculty Research Philosophy Department 2011 Reason and Necessity: The Descent of the Philosopher Kings Damian Caluori Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/phil_faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Repository Citation Caluori, D. (2011). Reason and necessity: The descent of the philosopher kings. Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, 40, 7-27. This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Damian Caluori, Reason and Necessity: the Descent of the Philosopher-Kings Reason and Necessity: the Descent of the Philosopher-Kings One of the reasons why one might find it worthwhile to study philosophers of late antiquity is the fact that they often have illuminating things to say about Plato and Aristotle. Plotinus, in particular, was a diligent and insightful reader of those great masters. Michael Frede was certainly of that view, and when he wrote that ”[o]ne can learn much more from Plotinus about Aristotle than from most modern accounts of the Stagirite”, he would not have objected, I presume, to the claim that Plotinus is also extremely helpful for the study of Plato.1 In this spirit I wish to discuss a problem that has occupied modern Plato scholars for a long time and I will present a Plotinian answer to that problem. The problem concerns the descent of the philosopher kings in Plato’s Republic. -

Chimpanzees Use of Sign Language

Chimpanzees’ Use of Sign Language* ROGER S. FOUTS & DEBORAH H. FOUTS Washoe was cross-fostered by humans.1 She was raised as if she were a deaf human child and so acquired the signs of American Sign Language. Her surrogate human family had been the only people she had really known. She had met other humans who occasionally visited and often seen unfamiliar people over the garden fence or going by in cars on the busy residential street that ran next to her home. She never had a pet but she had seen dogs at a distance and did not appear to like them. While on car journeys she would hang out of the window and bang on the car door if she saw one. Dogs were obviously not part of 'our group'; they were different and therefore not to be trusted. Cats fared no better. The occasional cat that might dare to use her back garden as a shortcut was summarily chased out. Bugs were not favourites either. They were to be avoided or, if that was impossible, quickly flicked away. Washoe had accepted the notion of human superiority very readily - almost too readily. Being superior has a very heady quality about it. When Washoe was five she left most of her human companions behind and moved to a primate institute in Oklahoma. The facility housed about twenty-five chimpanzees, and this was where Washoe was to meet her first chimpanzee: imagine never meeting a member of your own species until you were five. After a plane flight Washoe arrived in a sedated state at her new home. -

Menagerie to Me / My Neighbor Be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900

“MENAGERIE TO ME / MY NEIGHBOR BE”: EXOTIC ANIMALS AND AMERICAN CONSCIENCE, 1840-1900 Leslie Jane McAbee A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Eliza Richards Timothy Marr Matthew Taylor Ruth Salvaggio Jane Thrailkill © 2018 Leslie Jane McAbee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Leslie McAbee: “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900 (Under the direction of Eliza Richards) Throughout the nineteenth century, large numbers of living “exotic” animals—elephants, lions, and tigers—circulated throughout the U.S. in traveling menageries, circuses, and later zoos as staples of popular entertainment and natural history education. In “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be,” I study literary representations of these displaced and sensationalized animals, offering a new contribution to Americanist animal studies in literary scholarship, which has largely attended to the cultural impact of domesticated and native creatures. The field has not yet adequately addressed the influence that representations of foreign animals had on socio-cultural discourses, such as domesticity, social reform, and white supremacy. I examine how writers enlist exoticized animals to variously advance and disrupt the human-centered foundations of hierarchical thinking that underpinned nineteenth-century tenets of civilization, particularly the belief that Western culture acts as a progressive force in a comparatively barbaric world. Both well studied and lesser-known authors, however, find “exotic” animal figures to be wily for two seemingly contradictory reasons. -

Ndume, and Hayes, J.J

Publications Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Hayes, J.J. (2003) Castration as a Viable Alternative to Zeta Male Propagation. J. Primate Behavior [in press]. Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Hayes, J.J. (2003) Identification of POZM-A Novel Protease That is Essential for Degradation of Zeta-Male Protein. Nature [in press]. Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Gorilla, T.T. (2001) A Critical Review of the Color Pink and Anger Management. J. Primate Behavior, 46: 8012-8021. Ndume, and Gorilla, T.T. (2001) Escalation of Dominance and Aberrant Behavior of Alpha-Males in the Presence of Alpha-Females. J. Primate Behavior, 45: 7384-7390. Ndume, Koko, Gorilla, T.T. (2001) The ëPound Head with Fistí is the Preferred Method of Establishment of Dominance by Alpha- males in Gorilla Society. J. Primate. Behavior, 33: 3753-3762. Graueri, G., Ndume, and Gorilla, E.P. (1996) Rate of Loss of Banana Peel Pigmentation after Banana Consumption. Anal. Chem., 42: 1570-85. Education Ph.D. in Behavioral Biology, Gorilla Foundation 2000 Cincinnati, OH. M.S. in Behavioral Etiquette 1998 Sponge Bob University for Primate Temperament Training. *Discharged from program for non-compliance. Ph.D. in Chemistry 1997 Silverback University, Zaire B.S. in Survival and Chemical Synthesis ? - 1995 The Jungle, Zaire Research Experience Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 2001 - Present Postdoctoral Fellow Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey J. Hayes Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 2000 - 2001 Postdoctoral Fellow Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey J. Hayes Department of Behavioral Biology, Gorilla Foundation, Cincinnati OH 1997 - 2000 Ph.D. -

Pre-Sleep and Sleeping Platform Construction Behavior in Captive Orangutans (Pongo Spp

Original Article Folia Primatol 2015;86:187–202 Received: July 28, 2014 DOI: 10.1159/000381056 Accepted after revision: February 18, 2015 Published online: May 13, 2015 Pre-Sleep and Sleeping Platform Construction Behavior in Captive Orangutans (Pongo spp. ): Implications for Ape Health and Welfare a b–d David R. Samson Rob Shumaker a b Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, N.C., Indianapolis c Zoo, VP of Conservation and Life Sciences, Indianapolis, Ind. , Indiana University, d Bloomington, Ind. , and Krasnow Institute at George Mason University, Fairfax, Va. , USA Key Words Orangutan · Sleep · Sleeping platform · Nest · Animal welfare · Ethology Abstract The nightly construction of a ‘nest’ or sleeping platform is a behavior that has been observed in every wild great ape population studied, yet in captivity, few analyses have been performed on sleep related behavior. Here, we report on such behavior in three female and two male captive orangutans (Pongo spp.), in a natural light setting, at the Indianapolis Zoo. Behavioral samples were generated, using infrared cameras for a total of 47 nights (136.25 h), in summer (n = 25) and winter (n = 22) periods. To characterize sleep behaviors, we used all-occurrence sampling to generate platform construction episodes (n = 217). Orangutans used a total of 2.4 (SD = 1.2) techniques and 7.5 (SD = 6.3) actions to construct a sleeping platform; they spent 10.1 min (SD – 9.9 min) making the platform and showed a 77% preference for ground (vs. elevated) sleep sites. Com- parisons between summer and winter platform construction showed winter start times (17:12 h) to be significantly earlier and longer in duration than summer start times (17:56 h). -

Early Modern Women Philosophers and the History of Philosophy

Early Modern Women Philosophers and the History of Philosophy EILEEN O’NEILL It has now been more than a dozen years since the Eastern Division of the APA invited me to give an address on what was then a rather innovative topic: the published contributions of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century women to philosophy.1 In that address, I highlighted the work of some sixty early modern women. I then said to the audience, “Why have I presented this somewhat interesting, but nonetheless exhausting . overview of seventeenth- and eigh- teenth-century women philosophers? Quite simply, to overwhelm you with the presence of women in early modern philosophy. It is only in this way that the problem of women’s virtually complete absence in contemporary histories of philosophy becomes pressing, mind-boggling, possibly scandalous.” My presen- tation had attempted to indicate the quantity and scope of women’s published philosophical writing. It had also suggested that an acknowledgment of their contributions was evidenced by the representation of their work in the scholarly journals of the period and by the numerous editions and translations of their texts that continued to appear into the nineteenth century. But what about the status of these women in the histories of philosophy? Had they ever been well represented within the histories written before the twentieth century? In the second part of my address, I noted that in the seventeenth century Gilles Menages, Jean de La Forge, and Marguerite Buffet produced doxogra- phies of women philosophers, and that one of the most widely read histories of philosophy, that by Thomas Stanley, contained a discussion of twenty-four women philosophers of the ancient world. -

The Philosopher-Prophet in Avicenna's Political Philosophy

The philosopher-prophet in Avicenna's political philosophy Author: James Winston Morris Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/4029 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Published in Political aspects of Islamic philosophy, pp. 152-198 Use of this resource is governed by the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons "Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States" (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/) The P~~losopher-Prophet in. AVic~nna's Political Philosophy. Chapter 4 of The PolItICal Aspects of IslamIc PhIlosophy, ed. C. Butterworth, Cambridge Harvard University Press, 1992, pp. 142-188. ' -FOUR- The Philosopher-Prophet in Avicenna~s Political Philosophy James W. Morris With time, human beings tend to take miracles for granted. Perhaps the most lasting and public of all miracles, those to which Islamic philosophers devoted so much of their reflections, were the political achievements of the prophets: how otherwise obscure figures like Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad came to shape the thoughts and actions of so much of civilized humanity. Within the high culture of Islamic civilization, the thought and writings of an itinerant Persian doctor and court administrator we know as Avicenna (370/980~28/1037) came to play a similarly central role: for almost a millenium, each of the tra ditions of Islamic thought claiming a wider, universal human validity has appealed either directly to his works or to logical and metaphysical disciplines whose Islamic forms were directly grounded in them. This study considers some of the central philosophic under pinnings of that achievement. -

The Philosopher-Priest and the Mythology of Reason

College of the Holy Cross CrossWorks Philosophy Faculty Scholarship Philosophy Department 2012 The hiP losopher-Priest and the Mythology of Reason John Panteleimon Manoussakis College of the Holy Cross, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://crossworks.holycross.edu/phil_fac_scholarship Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Manoussakis, John Panteleimon. The hiP losopher-Priest and the Mythology of Reason. Analecta Hermeneutica, [S.l.], n. 4, May 2012. ISSN 1918-7351. Available at: http://journals.library.mun.ca/ojs/index.php/analecta/article/view/707/607 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of CrossWorks. ISSN 1918-7351 Volume 4 (2012) The Philosopher-Priest and the Mythology of Reason John Panteleimon Manoussakis Though much of ideology’s dangers for religion have been the subject of recent scholarly discussion, ranging from religion’s ontological commitments to its self- captivity in the land of conceptual idolatry, far less noticed has remained, to the scholarly eye in any case, the counter risk of philosophy’s aspirations to usurp the salvific role of religion. Lofty aspirations which, although never quite admitted as such, are kept hidden under what philosophy has always, or almost always, considered as its principal duty: namely, the supersession (read, incorporation or substitution1) of religion by one or the other speculative systems. This, in fact, was an accusation brought against philosophy (and philosophers) by none other than Nietzsche who, in his work appropriately named Twilight of the Idols, writes: All that philosophers have handled for thousands of years have been concept-mummies [Begriffs-Mumien]; nothing real escaped their grasp alive. -

The Case for the Personhood of the Gorillas

The Case for the Personhood of Gorillas* FRANCINE PATTERSON & WENDY GORDON We present this individual for your consideration: She communicates in sign language, using a vocabulary of over 1,000 words. She also understands spoken English, and often carries on 'bilingual' conversations, responding in sign to questions asked in English. She is learning the letters of the alphabet, and can read some printed words, including her own name. She has achieved scores between 85 and 95 on the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test. She demonstrates a clear self-awareness by engaging in self-directed behaviours in front of a mirror, such as making faces or examining her teeth, and by her appropriate use of self- descriptive language. She lies to avoid the consequences of her own misbehaviour, and anticipates others' responses to her actions. She engages in imaginary play, both alone and with others. She has produced paintings and drawings which are representational. She remembers and can talk about past events in her life. She understands and has used appropriately time- related words like 'before', 'after', 'later', and 'yesterday'. She laughs at her own jokes and those of others. She cries when hurt or left alone, screams when frightened or angered. She talks about her feelings, using words like 'happy', 'sad', 'afraid', 'enjoy', 'eager', 'frustrate', 'mad' and, quite frequently, 'love'. She grieves for those she has lost- a favourite cat who has died, a friend who has gone away. She can talk about what happens when one dies, but she becomes fidgety and uncomfortable when asked to discuss her own death or the death of her companions. -

4 a Complex-Adaptive-Systems Approach to the Evolution of Language and the Brain

- 4 A Complex-Adaptive-Systems Approach to the Evolution of Language and the Brain P Thomas Schoenemann 1 Introduction Language has arguably been as important to our species' evolutionary success as has any other behavior. Understanding how language evolved is therefore one of the most interesting questions in evolutionary biology. Part of this story involves understanding the evolutionary changes in our biology, particularly our brain. However, these changes cannot themselves be understood indepen dent of the behavioral effectsthey made possible. The complexity of our inner mental world - what will here be referred to as conceptual complexity- is one critical result of the evolution of our brain, and it will be argued that this has in turn led to the evolution oflanguage structure via cultural mechanisms (many of which remain opaque and hidden fromour conscious awareness). From this per spective, the complexity oflanguage is the result of the evolution ofcomplexity in brain circuits underlying our conceptual awareness. However, because indi vidual brains mature in the context of an intensely interactive social existence - one that is typical of primates generally but is taken to an unprecedented level among modern humans - cultural evolution of language has itself contributed to a richer conceptual world. This in turn has produced evolutionary pressures to enhance brain circuits primed to learn such complexity. The dynamics oflan guage evolution, involving brain/behavior co-evolution in this way, make it a prime example of what have been called "complex adaptive systems" (Beckner et al. 2009). Complex adaptive systems are phenomena that result fromthe interaction of many individual components as they adapt and learn fromeach other (Holland 2006).