The Case for the Personhood of the Gorillas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Koko

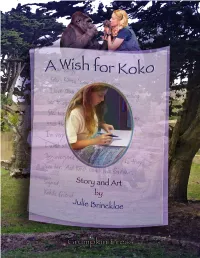

1 A Wish for Koko by Julie Brinckloe 2 This book was created as a gift to the Gorilla Foundation. 100% of the proceeds will go directly to the Foundation to help all the Kokos of the World. Copyright © by Julie Brinckloe 2019 Grumpkin Press All rights reserved. Photographs and likenesses of Koko, Penny and Michael © by Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation Koko’s Kitten © by Penny Patterson, Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation No part of this book may be used or reproduced in whole or in part without prior written consent of Julie Brinckloe and the Gorilla Foundation. Library of Congress U.S. Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 2-131-759 ISBN 978-0-578-51838-1 Printed in the U.S.A. 0 Thank You This story needed inspired players to give it authenticity. I found them at La Honda Elementary School, a stone’s throw from where Koko lived her extraordinary life. And I found it in the spirited souls of Stella Machado and her family. Principal Liz Morgan and teacher Brett Miller embraced Koko with open hearts, and the generous consent of parents paved the way for students to participate in the story. Ms. Miller’s classroom was the creative, warm place I had envisioned. And her fourth and fifth grade students were the kids I’d crossed my fingers for. They lit up the story with exuberance, inspired by true affection for Koko and her friends. I thank them all. And following the story they shall all be named. I thank the San Francisco Zoo for permission to use my photographs taken at the Gorilla Preserve in this book. -

Chimpanzees Use of Sign Language

Chimpanzees’ Use of Sign Language* ROGER S. FOUTS & DEBORAH H. FOUTS Washoe was cross-fostered by humans.1 She was raised as if she were a deaf human child and so acquired the signs of American Sign Language. Her surrogate human family had been the only people she had really known. She had met other humans who occasionally visited and often seen unfamiliar people over the garden fence or going by in cars on the busy residential street that ran next to her home. She never had a pet but she had seen dogs at a distance and did not appear to like them. While on car journeys she would hang out of the window and bang on the car door if she saw one. Dogs were obviously not part of 'our group'; they were different and therefore not to be trusted. Cats fared no better. The occasional cat that might dare to use her back garden as a shortcut was summarily chased out. Bugs were not favourites either. They were to be avoided or, if that was impossible, quickly flicked away. Washoe had accepted the notion of human superiority very readily - almost too readily. Being superior has a very heady quality about it. When Washoe was five she left most of her human companions behind and moved to a primate institute in Oklahoma. The facility housed about twenty-five chimpanzees, and this was where Washoe was to meet her first chimpanzee: imagine never meeting a member of your own species until you were five. After a plane flight Washoe arrived in a sedated state at her new home. -

When Koko the Gorilla Needs a Checkup, Stanford Docs Swing Into Action by Mitzi Baker N August 8Th, Dr

When Koko the Gorilla Needs a Checkup, Stanford Docs Swing into Action By Mitzi Baker n August 8th, Dr. Fred Mihm and a team of Stanford Ocolleagues reported to the nearby Woodside abode of Koko, the 33-year-old lowland gorilla famous for her ability to communicate through American Sign Language. The medical team’s visit was prompt- ed by an aching tooth. Using the gesture for pain and pointing to her Anesthesiologists Fred Mihm (right) and Ethan mouth, Koko recently told her han- Jackson (center), working with veterinarian John Ochsenreifer (left), attend to Koko the dlers that her level of pain was an gorilla after she has been sedated for a recent eight or nine on a scale of 10. The medical workup that took five hours. With the Gorilla Foundation contacted Mihm, exception of dental problems, Koko was found who has consulted with the San to be in good health. Photo: Courtesy of Ron Cohn, Francisco Zoo for years and has anes- The Gorilla Foundation thetized lions, tigers, giraffes and elephants in addition to gorillas, about join- ing a team of veterinarians and dentists to treat Koko’s painful tooth. The use of anesthesia can be a risky proposition for animals, so it is used only when deemed essential, Mihm said. Because the dental surgery required anesthesia, doctors felt it would give them the perfect opportunity to take an in-depth look at Koko’s overall health. Gorillas suffer from many of the same maladies as humans, Mihm said, so it makes sense for veterinarians and medical doctors to collaborate. -

Menagerie to Me / My Neighbor Be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900

“MENAGERIE TO ME / MY NEIGHBOR BE”: EXOTIC ANIMALS AND AMERICAN CONSCIENCE, 1840-1900 Leslie Jane McAbee A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Eliza Richards Timothy Marr Matthew Taylor Ruth Salvaggio Jane Thrailkill © 2018 Leslie Jane McAbee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Leslie McAbee: “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be”: Exotic Animals and American Conscience, 1840-1900 (Under the direction of Eliza Richards) Throughout the nineteenth century, large numbers of living “exotic” animals—elephants, lions, and tigers—circulated throughout the U.S. in traveling menageries, circuses, and later zoos as staples of popular entertainment and natural history education. In “Menagerie to me / My Neighbor be,” I study literary representations of these displaced and sensationalized animals, offering a new contribution to Americanist animal studies in literary scholarship, which has largely attended to the cultural impact of domesticated and native creatures. The field has not yet adequately addressed the influence that representations of foreign animals had on socio-cultural discourses, such as domesticity, social reform, and white supremacy. I examine how writers enlist exoticized animals to variously advance and disrupt the human-centered foundations of hierarchical thinking that underpinned nineteenth-century tenets of civilization, particularly the belief that Western culture acts as a progressive force in a comparatively barbaric world. Both well studied and lesser-known authors, however, find “exotic” animal figures to be wily for two seemingly contradictory reasons. -

Vadonban, Is, Akiket Különösebben Nem Is Érdekel a De Már Jó Ideje Nyoma Veszett

HÍREK HÓPEHELYRŐL- MEG HÍRES GORILLÁKRÓL ÁLTALÁBAN... Hópehely 40 éves! Ma ő talán emeli meg, hogy alattuk rovarokat keresgél Világhírű gorillák jen. Eddig 21 ivadékot nemzett, de sajnos a leghíresebb „ állatszemélyiség” ezekből csak hat érte meg a felnőttkort. Hópelyhen kívül még jó néhány világhírű gorillát is az egész világon. Nem hiszem, Egyikük sem hasonlított apjára: mindegyik merünk. Ezek egyike Colo, aki 1956 december 22- „szabványos” fekete lett. Kivételt képezett hogy valaha többet mondtak vagy az az ikerpár, melyet 1999-ben láttunk a én született az ohioi Columbus város állatkertjében. írtak volna egy gorilláról, mert még barcelonai állatkertben: ezek egyikének Nevezetes állatnak számít, mert ő volt az első állat kertben született gorilla. 46 életévével ma egyike az Internet Google keresője is vagy középső két ujján fehér, pigmenthiányos folt volt, jelezve az atyai örökséget. a legöregebb gorillahölgyeknek. Í 3 5 0 helyen tartja nyilván angol A baseli születésű Jambo volt az első állatkertben nevén, Snowflake-ként született gorilla, melyet anyja önállóan nevelt fel. Ez már önmagában is híressé tette a kis Jambót, de igazi világhírre akkor tett szert, amikor a nyolcvanas Hírnevét elsősorban annak köszönheti, években „elsősegélyben részesített" egy kifutójába hogy ő az egyetlen ismert fehér gorilla.1 Az esett kisfiút. afrikai Guineában, 1966-ban került fogság ba, feltehetően négyéves korában. Egy ép pen arra járó természetbúvár száz dollárért Koko kisbabára vágyik megvette, és egy hátizsákban Barcelonába szállította. Az ottani állatkertben talált vég Hópehely kétségtelenül a legismertebb, de Koko, leges otthonra. Kapott is spanyol nevet ízi- a „beszélő gorilla" talán még több figyelmet érde ben: Capito de Nieve, de az ottani köztudat melne. -

Ndume, and Hayes, J.J

Publications Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Hayes, J.J. (2003) Castration as a Viable Alternative to Zeta Male Propagation. J. Primate Behavior [in press]. Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Hayes, J.J. (2003) Identification of POZM-A Novel Protease That is Essential for Degradation of Zeta-Male Protein. Nature [in press]. Vitolo, J.M., Ndume, and Gorilla, T.T. (2001) A Critical Review of the Color Pink and Anger Management. J. Primate Behavior, 46: 8012-8021. Ndume, and Gorilla, T.T. (2001) Escalation of Dominance and Aberrant Behavior of Alpha-Males in the Presence of Alpha-Females. J. Primate Behavior, 45: 7384-7390. Ndume, Koko, Gorilla, T.T. (2001) The ëPound Head with Fistí is the Preferred Method of Establishment of Dominance by Alpha- males in Gorilla Society. J. Primate. Behavior, 33: 3753-3762. Graueri, G., Ndume, and Gorilla, E.P. (1996) Rate of Loss of Banana Peel Pigmentation after Banana Consumption. Anal. Chem., 42: 1570-85. Education Ph.D. in Behavioral Biology, Gorilla Foundation 2000 Cincinnati, OH. M.S. in Behavioral Etiquette 1998 Sponge Bob University for Primate Temperament Training. *Discharged from program for non-compliance. Ph.D. in Chemistry 1997 Silverback University, Zaire B.S. in Survival and Chemical Synthesis ? - 1995 The Jungle, Zaire Research Experience Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 2001 - Present Postdoctoral Fellow Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey J. Hayes Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY 2000 - 2001 Postdoctoral Fellow Advisor: Dr. Jeffrey J. Hayes Department of Behavioral Biology, Gorilla Foundation, Cincinnati OH 1997 - 2000 Ph.D. -

Pre-Sleep and Sleeping Platform Construction Behavior in Captive Orangutans (Pongo Spp

Original Article Folia Primatol 2015;86:187–202 Received: July 28, 2014 DOI: 10.1159/000381056 Accepted after revision: February 18, 2015 Published online: May 13, 2015 Pre-Sleep and Sleeping Platform Construction Behavior in Captive Orangutans (Pongo spp. ): Implications for Ape Health and Welfare a b–d David R. Samson Rob Shumaker a b Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, Duke University, Durham, N.C., Indianapolis c Zoo, VP of Conservation and Life Sciences, Indianapolis, Ind. , Indiana University, d Bloomington, Ind. , and Krasnow Institute at George Mason University, Fairfax, Va. , USA Key Words Orangutan · Sleep · Sleeping platform · Nest · Animal welfare · Ethology Abstract The nightly construction of a ‘nest’ or sleeping platform is a behavior that has been observed in every wild great ape population studied, yet in captivity, few analyses have been performed on sleep related behavior. Here, we report on such behavior in three female and two male captive orangutans (Pongo spp.), in a natural light setting, at the Indianapolis Zoo. Behavioral samples were generated, using infrared cameras for a total of 47 nights (136.25 h), in summer (n = 25) and winter (n = 22) periods. To characterize sleep behaviors, we used all-occurrence sampling to generate platform construction episodes (n = 217). Orangutans used a total of 2.4 (SD = 1.2) techniques and 7.5 (SD = 6.3) actions to construct a sleeping platform; they spent 10.1 min (SD – 9.9 min) making the platform and showed a 77% preference for ground (vs. elevated) sleep sites. Com- parisons between summer and winter platform construction showed winter start times (17:12 h) to be significantly earlier and longer in duration than summer start times (17:56 h). -

Learned Vocal and Breathing Behavior in an Enculturated Gorilla

Anim Cogn (2015) 18:1165–1179 DOI 10.1007/s10071-015-0889-6 ORIGINAL PAPER Learned vocal and breathing behavior in an enculturated gorilla 1 2 Marcus Perlman • Nathaniel Clark Received: 15 December 2014 / Revised: 5 June 2015 / Accepted: 16 June 2015 / Published online: 3 July 2015 Ó Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Abstract We describe the repertoire of learned vocal and relatively early into the evolution of language, with some breathing-related behaviors (VBBs) performed by the rudimentary capacity in place at the time of our last enculturated gorilla Koko. We examined a large video common ancestor with great apes. corpus of Koko and observed 439 VBBs spread across 161 bouts. Our analysis shows that Koko exercises voluntary Keywords Breath control Á Gorilla Á Koko Á Multimodal control over the performance of nine distinctive VBBs, communication Á Primate vocalization Á Vocal learning which involve variable coordination of her breathing, lar- ynx, and supralaryngeal articulators like the tongue and lips. Each of these behaviors is performed in the context of Introduction particular manual action routines and gestures. Based on these and other findings, we suggest that vocal learning and Examining the vocal abilities of great apes is crucial to the ability to exercise volitional control over vocalization, understanding the evolution of human language and speech particularly in a multimodal context, might have figured since we diverged from our last common ancestor. Many theories on the origins of language begin with two basic premises concerning the vocal behavior of nonhuman pri- mates, especially the great apes. They assume that (1) apes (and other primates) can exercise only negligible volitional control over the production of sound with their vocal tract, and (2) they are unable to learn novel vocal behaviors beyond their species-typical repertoire (e.g., Arbib et al. -

Picture This! Compiled by WSRA’S Children’S Literature Committee for the 2017 Convention from Titles Published Between September 2015-December 2016

Picture This! Compiled by WSRA’s Children’s Literature Committee for the 2017 Convention from titles published between September 2015-December 2016 Committee members dedicate themselves to reading widely to evaluate the newest books published each year, in order to recommend the most interesting and valuable books for educators and children to read. Submitted and nominated titles are evaluated based on appeal for students and value for classroom use; while representing high-quality literature with a focus on diversity, authenticity, real-world awareness, thought-provoking response, engaging storytelling, artistry of writing craft, and exemplary illustrations. A Beetle is Shy by Dianna Hutts Aston, illustrated by Sylvia Long (Chronicle Books, 2016). The award-winning duo of Dianna Hutts Aston and Sylvia Long team up again, this time creating a gorgeous look at the fascinating world of beetles. From flea beetles to bombardier beetles, an incredible variety of these beloved bugs are showcased here in all their splendor. Poetic in voice and elegant in design, this carefully researched and visually striking book is perfect for sparking children's imaginations in both classroom reading circles and home libraries. A Big Surprise for Little Card by Charise Mericle Harper, illustrated by Anna Raff (Candlewick Press, 2016). In the world of cards, each one has a special job to do. But is any card as lucky as Little Card? He's going to school to become a birthday card — in other words, to sing, play games, eat cake, and be happy all day long. Offbeat and utterly endearing, this tale of a little guy who gives it all he's got is complete with a sweet twist and a surprise ending. -

A Theology for Koko Continued from Page 1 and Transgender People in the Sacramental Life of the Church While Resisting Further Discrimination

GTU Where religion meets the world news of the Graduate Theological Union Spring 2011 Building a world where many voices A Theology are heard: 2 Daniel Groody/ for Koko Immigration 4 Ruth Myers/ Same-Gender Blessings 6 Doug Herst/Creating …and all a Diverse Community 7 GTU News creatures 9 GTU great and ANNUAL small REPORT 2009 – 2010 Koko signs “Love” Copyright © 2011 The Gorilla Foundation / Koko.org Photo by Ronald Cohn ast summer, Ph.D. Candidate Marilyn chimpanzee, Washoe, focuses her current work Matevia returned to the Gorilla on the ethics side of conservation. “Western- L Foundation to visit Koko, the 40-year- ers in general think of justice in terms of a old lowland gorilla who learned to speak social contract, and non-human animal inter- American Sign Language and to understand ests are largely excluded because animals don’t English when she was a baby. Koko, known fit our beliefs about the kinds of beings who A mass extinction best for her communication skills with a get to participate in the contract,” she says. “ vocabulary of more than 1000 signs and a “I want to encourage humans to give more event caused by good understanding of spoken English, is the weight to the interests of other animals when human activities chief ambassador for her critically endangered those interests conflict and collide with our is a crisis of species. Matevia hadn’t seen Koko since own. My thesis, Casting the Net: Prospects working with her as a research associate from Toward a Theory of Social Justice for All, poses morality, spirituality, 1997 to 2000. -

A Genome-Wide Survey of Genetic Variation in Gorillas Using Reduced Representation Sequencing

1 A genome-wide survey of genetic variation in gorillas using reduced representation sequencing Aylwyn Scally1,2*, Bryndis Yngvadottir1,3*, Yali Xue1, Qasim Ayub1, Richard Durbin1, Chris Tyler- Smith1 *Equal contribution 1The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambs. CB10 1SA, UK. 2Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 3EH, UK 3Division of Biological Anthropology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 1QH, UK Keywords: Gorilla; western lowland; eastern lowland; beringei; graueri; genome; sequencing; genetic variation; genetic diversity; heterozygosity; inbreeding; allele sharing; population differentiation; population substructure; demography; centromere; telomere; major histocompatibility locus; MHC; HLA; selective sweep; conservation 2 Abstract All non-human great apes are endangered in the wild, and it is therefore important to gain an understanding of their demography and genetic diversity. To date, however, genetic studies within these species have largely been confined to mitochondrial DNA and a small number of other loci. Here, we present a genome-wide survey of genetic variation in gorillas using a reduced representation sequencing approach, focusing on the two lowland subspecies. We identify 3,274,491 polymorphic sites in 14 individuals: 12 western lowland gorillas (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) and 2 eastern lowland gorillas (Gorilla beringei graueri). We find that the two species are genetically distinct, based on levels of heterozygosity and patterns of allele sharing. Focusing on the western lowland population, we observe evidence for population substructure, and a deficit of rare genetic variants suggesting a recent episode of population contraction. In western lowland gorillas, there is an elevation of variation towards telomeres and centromeres on the chromosomal scale. -

Non-Human Primates and Language: Paper

Non-human primates and language: paper http://www.angelfire.com/sc2/nhplanguage/ftpaper.html Language competence in NHPs An assessment of the field in the light of a 'universal grammar' "The Berlin wall is down, and so is the wall that separates man from chimpanzee." (Elizabeth Bates) "There is no debate, so I have no opinion." (Noam Chomsky) 0 Introduction The language competence of non-human primates is one of the most controversial issues in present-day linguistics, with disbelief ranging from bored indifference to vitriolic accusations of fraud. The present paper aims to assess the current state of debate from an open-minded, critical and detached perspective. In a first part, a brief outline of earlier research in the language abilities of non-human primates - more precisely of apes (bonobos, urang-utangs, chimpanzees and gorillas) - is sketched. The second part focusses on the landmark studies published by Dr. Emily Sue Savage-Rumbaugh and her colleagues. A third section looks into the views of the Chomskyan field, leading up to the concluding section on the innateness debate. 1 Early research on non-human primates' capability for language 1.1 Attempts to teach NHPs to speak The language capability of non-human primates has been a subject of research since the beginning of this century. In 1909 already did Witmer attempt to teach a chimpanzee to talk. He claims that the chimpanzee was capable of articulating the word ‘mama’. In 1916 Furness taught an orang-utan to say the words ‘papa’ and ‘cup’. After the unexpected death of this orang-utan, Kellogg and Kellogg wanted to follow up this work.