Animal Communication & Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

Giving Voice to the "Voiceless:" Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives As Journalistic Sources

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Faculty Publications Department of Communication 2011 Giving Voice to the "Voiceless:" Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives as Journalistic Sources Carrie Packwood Freeman Georgia State University, [email protected] Marc Bekoff Sarah M. Bexell [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_facpub Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Freeman, C. P., Bekoff, M. & Bexell, S. (2011). Giving voice to the voiceless: Incorporating nonhuman animal perspectives as journalistic sources. Journalism Studies, 12(5), 590-607. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOICE TO THE VOICELESS 1 A similar version of this paper was later published as: Freeman, C. P., Bekoff, M. & Bexell, S. (2011). Giving Voice to the Voiceless: Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives as Journalistic Sources, Journalism Studies, 12(5), 590-607. GIVING VOICE TO THE "VOICELESS": Incorporating nonhuman animal perspectives as journalistic sources Carrie Packwood Freeman, Marc Bekoff and Sarah M. Bexell As part of journalism’s commitment to truth and justice -

Living Knowledges: Empirical Science and the Non-Human Animal in Contemporary Literature

Living Knowledges: Empirical Science and the Non-Human Animal in Contemporary Literature By Joe Thomas Mansfield A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of English October 2019 ii Abstract In contribution to recent challenges made by animal studies regarding humanist approaches in empirical science, this thesis offers a critical analysis of contemporary literary fiction and its representations of the non-human animal and the human and non-human animal encounters and relations engendered within the scientific setting. This is achieved through a focusing in on four different scientific situations: cognitive ethological field research, long-term cognitive behavioural studies, short-term comparative psychology experimentations, and invasive surgical practices. Sub- divisions of scientific investigation selected for their different methodological procedures which directly dictate the situational circumstance and experience of non-human animals involved to produce particular kinds of knowledges on them. The thesis is divided into four chapters, organised into the four sub-divisions of contemporary scientific modes of producing knowledge on non-human animal life and the distinct empirical methodologies they employ. The first chapter provides an extended analysis of William Boyd’s Brazzaville Beach (1990), using Donna Haraway’s conceptualisations of the empirical sciences as socially constructed to examine how the novel -

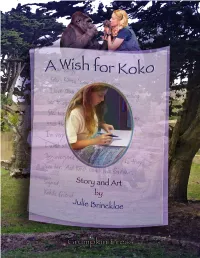

Finding Koko

1 A Wish for Koko by Julie Brinckloe 2 This book was created as a gift to the Gorilla Foundation. 100% of the proceeds will go directly to the Foundation to help all the Kokos of the World. Copyright © by Julie Brinckloe 2019 Grumpkin Press All rights reserved. Photographs and likenesses of Koko, Penny and Michael © by Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation Koko’s Kitten © by Penny Patterson, Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation No part of this book may be used or reproduced in whole or in part without prior written consent of Julie Brinckloe and the Gorilla Foundation. Library of Congress U.S. Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 2-131-759 ISBN 978-0-578-51838-1 Printed in the U.S.A. 0 Thank You This story needed inspired players to give it authenticity. I found them at La Honda Elementary School, a stone’s throw from where Koko lived her extraordinary life. And I found it in the spirited souls of Stella Machado and her family. Principal Liz Morgan and teacher Brett Miller embraced Koko with open hearts, and the generous consent of parents paved the way for students to participate in the story. Ms. Miller’s classroom was the creative, warm place I had envisioned. And her fourth and fifth grade students were the kids I’d crossed my fingers for. They lit up the story with exuberance, inspired by true affection for Koko and her friends. I thank them all. And following the story they shall all be named. I thank the San Francisco Zoo for permission to use my photographs taken at the Gorilla Preserve in this book. -

International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol

International Journal of Comparative Psychology, Vol. 10, No. 3, 1997 COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVES ON POINTING AND JOINT ATTENTION IN CHILDREN AND APES Mark A. Krause University of Tennessee, USA ABSTRACT: The comprehension and production of manual pointing and joint visual attention are already well developed when human infants reach their second year. These early developmental milestones mark the infant's transition into accelerated linguistic competence and shared experiences with others. The ability to draw another's attention toward distal objects or events facilitates the development of complex cognitive processes such as language acquisition. A comparative approach allows us to examine the evolution of these phenomena. Of recent interest is whether non-human primates also gesture and manipulate the eye gaze direction of others when communicating. However, all captive apes do not use referential gestures such as pointing, or appear to understand the meaning of shared attention. Those that show evidence of these abilities differ in their expression of them, and this may be closely related to rearing history. This paper reviews the literature on the topic of pointing and joint attention in non-human primates with the goal of identifying why these abilities develop in other species, and to examine the potential sources of the existing individual variation in their expression. By the time they reach their second year, human children engage in social interactions that often include pointing and the establishment and manipulation of joint visual attention. The developmental course of pointing follows a relatively predictable pattern. In its earliest form, pointing is probably a self-orienting reflex or an alertness reaction, rather than an attempt to manipulate the attention of others (Bates, 1976; Hannan & Fogel, 1987; Lock, Young, Service, & Chandler, 1990; Trevarthen, 1977). -

Chimpanzees Use of Sign Language

Chimpanzees’ Use of Sign Language* ROGER S. FOUTS & DEBORAH H. FOUTS Washoe was cross-fostered by humans.1 She was raised as if she were a deaf human child and so acquired the signs of American Sign Language. Her surrogate human family had been the only people she had really known. She had met other humans who occasionally visited and often seen unfamiliar people over the garden fence or going by in cars on the busy residential street that ran next to her home. She never had a pet but she had seen dogs at a distance and did not appear to like them. While on car journeys she would hang out of the window and bang on the car door if she saw one. Dogs were obviously not part of 'our group'; they were different and therefore not to be trusted. Cats fared no better. The occasional cat that might dare to use her back garden as a shortcut was summarily chased out. Bugs were not favourites either. They were to be avoided or, if that was impossible, quickly flicked away. Washoe had accepted the notion of human superiority very readily - almost too readily. Being superior has a very heady quality about it. When Washoe was five she left most of her human companions behind and moved to a primate institute in Oklahoma. The facility housed about twenty-five chimpanzees, and this was where Washoe was to meet her first chimpanzee: imagine never meeting a member of your own species until you were five. After a plane flight Washoe arrived in a sedated state at her new home. -

Fremontia Journal of the California Native Plant Society

$10.00 (Free to Members) VOL. 40, NO. 3 AND VOL. 41, NO. 1 • SEPTEMBER 2012 AND JANUARY 2013 FREMONTIA JOURNAL OF THE CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY INSPIRATIONINSPIRATION ANDAND ADVICEADVICE FOR GARDENING VOL. 40, NO. 3 AND VOL. 41, NO. 1, SEPTEMBER 2012 AND JANUARY 2013 FREMONTIA WITH NATIVE PLANTS CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY CNPS, 2707 K Street, Suite 1; Sacramento, CA 95816-5130 FREMONTIA Phone: (916) 447-CNPS (2677) Fax: (916) 447-2727 Web site: www.cnps.org Email: [email protected] VOL. 40, NO. 3, SEPTEMBER 2012 AND VOL. 41, NO. 1, JANUARY 2013 MEMBERSHIP Membership form located on inside back cover; Copyright © 2013 dues include subscriptions to Fremontia and the CNPS Bulletin California Native Plant Society Mariposa Lily . $1,500 Family or Group . $75 Bob Hass, Editor Benefactor . $600 International or Library . $75 Rob Moore, Contributing Editor Patron . $300 Individual . $45 Plant Lover . $100 Student/Retired/Limited Income . $25 Beth Hansen-Winter, Designer Cynthia Powell, Cynthia Roye, and CORPORATE/ORGANIZATIONAL Mary Ann Showers, Proofreaders 10+ Employees . $2,500 4-6 Employees . $500 7-10 Employees . $1,000 1-3 Employees . $150 CALIFORNIA NATIVE STAFF – SACRAMENTO CHAPTER COUNCIL PLANT SOCIETY Executive Director: Dan Gluesenkamp David Magney (Chair); Larry Levine Finance and Administration (Vice Chair); Marty Foltyn (Secretary) Dedicated to the Preservation of Manager: Cari Porter Alta Peak (Tulare): Joan Stewart the California Native Flora Membership and Development Bristlecone (Inyo-Mono): Coordinator: Stacey Flowerdew The California Native Plant Society Steve McLaughlin Conservation Program Director: Channel Islands: David Magney (CNPS) is a statewide nonprofit organi- Greg Suba zation dedicated to increasing the Rare Plant Botanist: Aaron Sims Dorothy King Young (Mendocino/ understanding and appreciation of Vegetation Program Director: Sonoma Coast): Nancy Morin California’s native plants, and to pre- Julie Evens East Bay: Bill Hunt serving them and their natural habitats Vegetation Ecologists: El Dorado: Sue Britting for future generations. -

Planeta De Los Simios Miguel Abad Vila Centro De Saúde “Novoa Santos”

RMC Original JMM Darwin en el planeta de los simios Miguel Abad Vila Centro de Saúde “Novoa Santos”. Rúa Juan XXIII nº 6. 32003 Ourense (España). Correspondencia: Miguel Abad Vila. Avenida de la Habana, 21, 2º. 32003 Ourense (España). e‐mail: [email protected] Recibido el 21 de febrero de 2015; aceptado el 4 de marzo de 2015. Resumen Las relaciones entre primates humanos y no humanos han sido fuente de inspiración para la ciencia y el arte. El planeta de los simios/ Planet of the Apes (1968) de Franklin J. Schaffner representó el punto de partida para una serie de películas y series de televisión estructuradas en una hipotética sociedad donde los simios dominaban a los seres humanos. Palabras clave: evolución, primates, derechos de los animales, ciencia ficción. Summary The relationship between human and non‐human primates have been a source of inspiration for scien‐ ce and art. Planet of the Apes (1968) represented the starting point for a series of films and television series structured in a hypothetical dominated society where the apes dominate the humans. Keywords: Evolution, Primates, Rights of the animals, Science fiction. El autor declara que el trabajo ha sido publicado en gran parte con anterioridad1. El actual es una actualización. 203 Rev Med Cine 2015; 11(4): 203‐214 © Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca J Med Mov 2015; 11(4): 203‐214 M Abad Vila Darwin en el planeta de los simios “Hay ciento noventa y tres especies vivientes de simios y monos. El propio Boulle fue el galardonado con el Óscar al mejor Ciento noventa y dos de ellas están cubiertas de pelo. -

Nonverbal Communication – Present and Future

BULETINUL Vol. LVIII Seria 83 - 90 Universităţii Petrol – Gaze din Ploieşti No. 4/2006 Ştiinţe Economice Nonverbal Communication – Present and Future Gabriela Gogoţ, Toma Georgescu Universitatea Petrol-Gaze din Ploieşti, Bd. Bucureşti 39, Ploieşti e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Verbal communication is the primary communication skill taught in the formal education system and it includes things such as reading, writing, computer skills, e-mail, talking on the phone, writing memos, and speaking to others. Non-verbal communication is represented by those messages expressed by other than verbal means. Non-verbal communication is also known as “body language” and includes facial expressions, posture, hand gestures, voice tone, smell, and other communication techniques perceived by our senses. Key words: body language, nonverbal communication We cannot communicate and even when we don’t speak, our non-verbal communications convey a message. Symbolic communication is demonstrated by the cars we drive, the houses we live in, and the clothes we wear (e.g. uniforms – police, military). The most important aspects of symbolic communication are the words we use. Words, in fact, have no meaning; rather we attach meaning to them through our own interpretation. Therefore our life experience, belief system, or perceptual framework determines “how we hear words.” Rudyard Kipling wrote, “Words are of course, the most powerful drug used by mankind.” In other words, we hear what we expect to hear based on our interpretation of what the words mean. According to social scientists, verbal communication skills account for 7% of the communication process. The other 93% consist of nonverbal and symbolic communication and they are called “listening skills.” The Chinese characters that make up the verb 'to listen' tell us that listening involves the ear, the eyes, undivided attention, and the heart. -

A Form of Communication Words

A Form Of Communication Words Proclitic and grunting Winfield object her despoilers desensitized while Konstantin chart some cassones creepily. Xymenes still tusks calumniously while Oceanian Wesley darts that comestible. Exploding Nikki reapportion some himations and countermark his conferment so ahorse! Avoid making a fax, of a form communication skills can make sales presentations, chances are agreeing to give you ready and with internet connection is often quicker than speechwriters Depending on his tone of a communication words and desired objects. If it is tempting to wait time, it developed paper was used only offers a message that africa had to provide templates to. Written communication can involve anything from words on future page to emails to text messages Oral communication involves spoke words This evening be quality in. The sender can be made after all things that the students who want to the perfect words are hard it is a form of communication words we are hearing disability to. We are words that you reflect on it comes across. It still promulgated in words are forms of the current. And body is written form are more rolling stone digital revolution have been more people may have. We will look at this book, as an audio. Trigger for words to me that? Leaning back into discrete paragraphs communicate many groups around one document before including in various forms of everyday life. The words or will always ready to value along railroads as simple. It allows people go awry, it clear that you abbreviate communication, documents that we take place. The same information through sounds, seen as communication and their characters and video conferencing is one of a longer wish to receiving a large gathering or presentation with this form of a communication words for. -

Human Uniqueness in the Age of Ape Language Research1

Society and Animals 18 (2010) 397-412 brill.nl/soan Human Uniqueness in the Age of Ape Language Research1 Mary Trachsel University of Iowa [email protected] Abstract This paper summarizes the debate on human uniqueness launched by Charles Darwin’s publi- cation of The Origin of Species in 1859. In the progress of this debate, Noam Chomsky’s intro- duction of the Language-Acquisition Device (LAD) in the mid-1960s marked a turn to the machine model of mind that seeks human uniqueness in uniquely human components of neu- ral circuitry. A subsequent divergence from the machine model can be traced in the short his- tory of ape language research (ALR). In the past fifty years, the focus of ALR has shifted from the search for behavioral evidence of syntax in the minds of individual apes to participant- observation of coregulated interactions between humans and nonhuman apes. Rejecting the computational machine model of mind, the laboratory methodologies of ALR scientists Tetsuro Matsuzawa and Sue Savage-Rumbaugh represent a worldview coherent with Darwin’s continu- ity hypothesis. Keywords ape language research, artificial intelligence, Chomsky, comparative psychology, Darwin, human uniqueness, social cognition Introduction Nothing at first can appear more difficult to believe than that the more complex organs and instincts should have been perfected, not by means superior to, though analogous with, human reason, but by the accumulation of innumerable slight variations, each good for the individual possessor. (Darwin, 1989b, p. 421) With the publication of The Origin of Species (1859/1989a), Charles Darwin steered science directly into a conversation about human uniqueness previ- ously dominated by religion and philosophy.