Language (Including Signjanguage)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

A Lexicostatistic Survey of the Signed Languages in Nepal

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2012-021 ® A Lexicostatistic Survey of the Signed Languages in Nepal Hope M. Hurlbut A Lexicostatistic Survey of the Signed Languages in Nepal Hope M. Hurlbut SIL International ® 2012 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2012-021, June 2012 © 2012 Hope M. Hurlbut and SIL International ® All rights reserved 2 Contents 0. Introduction 1.0 The Deaf 1.1 The deaf of Nepal 1.2 Deaf associations 1.3 History of deaf education in Nepal 1.4 Outside influences on Nepali Sign Language 2.0 The Purpose of the Survey 3.0 Research Questions 4.0 Approach 5.0 The survey trip 5.1 Kathmandu 5.2 Surkhet 5.3 Jumla 5.4 Pokhara 5.5 Ghandruk 5.6 Dharan 5.7 Rajbiraj 6.0 Methodology 7.0 Analysis and results 7.1 Analysis of the wordlists 7.2 Interpretation criteria 7.2.1 Results of the survey 7.2.2 Village signed languages 8.0 Conclusion Appendix Sample of Nepali Sign Language Wordlist (Pages 1–6) References 3 Abstract This report concerns a 2006 lexicostatistical survey of the signed languages of Nepal. Wordlists and stories were collected in several towns of Nepal from Deaf school leavers who were considered to be representative of the Nepali Deaf. In each city or town there was a school for the Deaf either run by the government or run by one of the Deaf Associations. The wordlists were transcribed by hand using the SignWriting orthography. Two other places were visited where it was learned that there were possibly unique sign languages, in Jumla District, and also in Ghandruk (a village in Kaski District). -

Conflict and Cooperation in Wild Chimpanzees

ADVANCES IN THE STUDY OF BEHAVIOR VOL. 35 Conflict and Cooperation in Wild Chimpanzees MARTIN N. MULLER* and JOHN C. MITANIt *DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY BOSTON UNIVERSITY BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS, 02215, USA tDEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ANN ARBOR, MICHIGAN, 48109, USA 1. INTRODUCTION The twin themes of competition and cooperation have been the focus of many studies in animal behavior (Alcock, 2001; Dugatkin, 2004; Krebs and Davies, 1997). Competition receives prominent attention because it forms the basis for the unifying, organizing principle of biology. Darwin's (1859) theory of natural selection furnishes a powerful framework to understand the origin and maintenance of organic and behavioral diversity. Because the process of natural selection depends on reproductive competition, aggression, dominance, and competition for mates serve as important foci of ethological research. In contrast, cooperation in animals is less easily explained within a Darwinian framework. Why do animals cooperate and behave in ways that benefit others? Supplements to the theory of natural selection in the form of kin selection, reciprocal altruism, and mutualism provide mechanisms that transform the study of cooperative behavior in animals into a mode of inquiry compatible with our current understand- ing of the evolutionary process (Clutton-Brock, 2002; Hamilton, 1964; Trivers, 1971). If cooperation can be analyzed via natural selection operating on indivi- duals, a new way to conceptualize the process emerges. Instead of viewing cooperation as distinct from competition, it becomes productive to regard them together. Students of animal behavior have long recognized that an artificial dichotomy may exist insofar as animals frequently cooperate to compete with conspecifics. -

Sign Language Endangerment and Linguistic Diversity Ben Braithwaite

RESEARCH REPORT Sign language endangerment and linguistic diversity Ben Braithwaite University of the West Indies at St. Augustine It has become increasingly clear that current threats to global linguistic diversity are not re - stricted to the loss of spoken languages. Signed languages are vulnerable to familiar patterns of language shift and the global spread of a few influential languages. But the ecologies of signed languages are also affected by genetics, social attitudes toward deafness, educational and public health policies, and a widespread modality chauvinism that views spoken languages as inherently superior or more desirable. This research report reviews what is known about sign language vi - tality and endangerment globally, and considers the responses from communities, governments, and linguists. It is striking how little attention has been paid to sign language vitality, endangerment, and re - vitalization, even as research on signed languages has occupied an increasingly prominent posi - tion in linguistic theory. It is time for linguists from a broader range of backgrounds to consider the causes, consequences, and appropriate responses to current threats to sign language diversity. In doing so, we must articulate more clearly the value of this diversity to the field of linguistics and the responsibilities the field has toward preserving it.* Keywords : language endangerment, language vitality, language documentation, signed languages 1. Introduction. Concerns about sign language endangerment are not new. Almost immediately after the invention of film, the US National Association of the Deaf began producing films to capture American Sign Language (ASL), motivated by a fear within the deaf community that their language was endangered (Schuchman 2004). -

Giving Voice to the "Voiceless:" Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives As Journalistic Sources

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Faculty Publications Department of Communication 2011 Giving Voice to the "Voiceless:" Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives as Journalistic Sources Carrie Packwood Freeman Georgia State University, [email protected] Marc Bekoff Sarah M. Bexell [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_facpub Part of the Journalism Studies Commons, and the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Freeman, C. P., Bekoff, M. & Bexell, S. (2011). Giving voice to the voiceless: Incorporating nonhuman animal perspectives as journalistic sources. Journalism Studies, 12(5), 590-607. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOICE TO THE VOICELESS 1 A similar version of this paper was later published as: Freeman, C. P., Bekoff, M. & Bexell, S. (2011). Giving Voice to the Voiceless: Incorporating Nonhuman Animal Perspectives as Journalistic Sources, Journalism Studies, 12(5), 590-607. GIVING VOICE TO THE "VOICELESS": Incorporating nonhuman animal perspectives as journalistic sources Carrie Packwood Freeman, Marc Bekoff and Sarah M. Bexell As part of journalism’s commitment to truth and justice -

The 5 Parameters of ASL Before You Begin Sign Language Partner Activities, You Need to Learn the 5 Parameters of ASL

The 5 Parameters of ASL Before you begin Sign Language Partner activities, you need to learn the 5 Parameters of ASL. You will use these parameters to describe new vocabulary words you will learn with your partner while completing Language Partner activities. Read and learn about the 5 Parameters below. DEFINITION In American Sign Language (ASL), we use the 5 Parameters of ASL to describe how a sign behaves within the signer’s space. The parameters are handshape, palm orientation, movement, location, and expression/non-manual signals. All five parameters must be performed correctly to sign the word accurately. Go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FrkGrIiAoNE for a signed definition of the 5 Parameters of ASL. Don’t forget to turn the captions on if you are a beginning ASL student. Note: The signer’s space spans the width of your elbows when your hands are on your hips to the length four inches above your head to four inches below your belly button. Imagine a rectangle drawn around the top half of your body. TYPES OF HANDSHAPES Handshapes consist of the manual alphabet and other variations of handshapes. Refer to the picture below. TYPES OF ORIENTATIONS Orientation refers to which direction your palm is facing for a particular sign. The different directions are listed below. 1. Palm facing out 2. Palm facing in 3. Palm is horizontal 4. Palm faces left/right 5. Palm toward palm 6. Palm up/down TYPES OF MOVEMENT A sign can display different kinds of movement that are named below. 1. In a circle 2. -

Building BSL Signbank: the Lemma Dilemma Revisited

Fenlon, Jordan, Kearsy Cormier & Adam Schembri. in press. Building BSL SignBank: The lemma dilemma revisited. International Journal of Lexicography. (Pre-proof draft: March 2015. Check for updates before citing.) 1 Building BSL SignBank: The lemma dilemma revisited Abstract One key criterion when creating a representation of the lexicon of any language within a dictionary or lexical database is that it must be decided which groups of idiosyncratic and systematically modified variants together form a lexeme. Few researchers have, however, attempted to outline such principles as they might apply to sign languages. As a consequence, some sign language dictionaries and lexical databases appear to be mixed collections of phonetic, phonological, morphological, and lexical variants of lexical signs (e.g. Brien 1992) which have not addressed what may be termed as the lemma dilemma. In this paper, we outline the lemmatisation practices used in the creation of BSL SignBank (Fenlon et al. 2014a), a lexical database and dictionary of British Sign Language based on signs identified within the British Sign Language Corpus (http://www.bslcorpusproject.org). We argue that the principles outlined here should be considered in the creation of any sign language lexical database and ultimately any sign language dictionary and reference grammar. Keywords: lemma, lexeme, lemmatisation, sign language, dictionary, lexical database. 1 Introduction When one begins to document the lexicon of a language, it is necessary to establish what one considers to be a lexeme. Generally speaking, a lexeme can be defined as a unit that refers to a set of words in a language that bear a relation to one another in form and meaning. -

Living Knowledges: Empirical Science and the Non-Human Animal in Contemporary Literature

Living Knowledges: Empirical Science and the Non-Human Animal in Contemporary Literature By Joe Thomas Mansfield A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities School of English October 2019 ii Abstract In contribution to recent challenges made by animal studies regarding humanist approaches in empirical science, this thesis offers a critical analysis of contemporary literary fiction and its representations of the non-human animal and the human and non-human animal encounters and relations engendered within the scientific setting. This is achieved through a focusing in on four different scientific situations: cognitive ethological field research, long-term cognitive behavioural studies, short-term comparative psychology experimentations, and invasive surgical practices. Sub- divisions of scientific investigation selected for their different methodological procedures which directly dictate the situational circumstance and experience of non-human animals involved to produce particular kinds of knowledges on them. The thesis is divided into four chapters, organised into the four sub-divisions of contemporary scientific modes of producing knowledge on non-human animal life and the distinct empirical methodologies they employ. The first chapter provides an extended analysis of William Boyd’s Brazzaville Beach (1990), using Donna Haraway’s conceptualisations of the empirical sciences as socially constructed to examine how the novel -

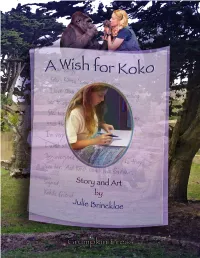

Finding Koko

1 A Wish for Koko by Julie Brinckloe 2 This book was created as a gift to the Gorilla Foundation. 100% of the proceeds will go directly to the Foundation to help all the Kokos of the World. Copyright © by Julie Brinckloe 2019 Grumpkin Press All rights reserved. Photographs and likenesses of Koko, Penny and Michael © by Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation Koko’s Kitten © by Penny Patterson, Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation No part of this book may be used or reproduced in whole or in part without prior written consent of Julie Brinckloe and the Gorilla Foundation. Library of Congress U.S. Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 2-131-759 ISBN 978-0-578-51838-1 Printed in the U.S.A. 0 Thank You This story needed inspired players to give it authenticity. I found them at La Honda Elementary School, a stone’s throw from where Koko lived her extraordinary life. And I found it in the spirited souls of Stella Machado and her family. Principal Liz Morgan and teacher Brett Miller embraced Koko with open hearts, and the generous consent of parents paved the way for students to participate in the story. Ms. Miller’s classroom was the creative, warm place I had envisioned. And her fourth and fifth grade students were the kids I’d crossed my fingers for. They lit up the story with exuberance, inspired by true affection for Koko and her friends. I thank them all. And following the story they shall all be named. I thank the San Francisco Zoo for permission to use my photographs taken at the Gorilla Preserve in this book. -

Chimpanzees Use of Sign Language

Chimpanzees’ Use of Sign Language* ROGER S. FOUTS & DEBORAH H. FOUTS Washoe was cross-fostered by humans.1 She was raised as if she were a deaf human child and so acquired the signs of American Sign Language. Her surrogate human family had been the only people she had really known. She had met other humans who occasionally visited and often seen unfamiliar people over the garden fence or going by in cars on the busy residential street that ran next to her home. She never had a pet but she had seen dogs at a distance and did not appear to like them. While on car journeys she would hang out of the window and bang on the car door if she saw one. Dogs were obviously not part of 'our group'; they were different and therefore not to be trusted. Cats fared no better. The occasional cat that might dare to use her back garden as a shortcut was summarily chased out. Bugs were not favourites either. They were to be avoided or, if that was impossible, quickly flicked away. Washoe had accepted the notion of human superiority very readily - almost too readily. Being superior has a very heady quality about it. When Washoe was five she left most of her human companions behind and moved to a primate institute in Oklahoma. The facility housed about twenty-five chimpanzees, and this was where Washoe was to meet her first chimpanzee: imagine never meeting a member of your own species until you were five. After a plane flight Washoe arrived in a sedated state at her new home.