Volume 4, No 2, October 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modelos Musicales En El Aula De 3º De ESO Y Su Relación Con La Educación En Valores."

Universidad Internacional de La Rioja Facultad de Educación Trabajo fin de máster "Modelos musicales en el aula de 3º de ESO y su relación con la educación en valores." Presentado por: Irene Rumayor Castell anos Línea de investigación: Educación , política y sociedad Director/a: Mª Cristina Fernández -Laso Ciudad: Pamplona Fecha: 15 de mayo de 2014 Máster de Formación de Profesorado de Secundaria - UNIR "Modelos musicales en los adolescentes de 3º ESO y su relación con la educación en valores" Agradecimientos A mi directora del Trabajo de Fin de Máster Mª Cristina Fernández-Laso por su gran dedicación e interés. A todos los profesores de la UNIR por dedicarme un poquito de su tiempo durante este máster. A mis alumnos de secundaria porque cada uno de ellos ha enriquecido mi camino descubriéndome cosas nuevas cada día. A mi familia y amigos por dedicarme todo el tiempo necesario independientemente de la hora del día o de la noche, siempre dispuestos a colaborar con interés y satisfacción. II Irene Rumayor Castellanos - 2014 Máster de Formación de Profesorado de Secundaria - UNIR "Modelos musicales en los adolescentes de 3º ESO y su relación con la educación en valores" RESUMEN Nos encontramos inmersos en un mundo sometido a constantes estímulos audiovisuales, lo cual no indica que estemos preparados para "digerir" toda esa cantidad de información, e incluso para enjuiciarla de manera crítica. La gravedad aumenta cuando hablamos de los adolescentes (14-16 años), ¿están preparados para discernir aspectos morales?, ¿con qué tipo de mensajes se encuentran?. En plena etapa de desarrollo, ¿asimilan la imagen que transmiten sus modelos?. -

Summer 2012 Boston Symphony Orchestra

boston symphony orchestra summer 2012 Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 131st season, 2011–2012 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Edmund Kelly, Chairman • Paul Buttenwieser, Vice-Chairman • Diddy Cullinane, Vice-Chairman • Stephen B. Kay, Vice-Chairman • Robert P. O’Block, Vice-Chairman • Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman • Stephen R. Weber, Vice-Chairman • Vincent M. O’Reilly, Treasurer William F. Achtmeyer • George D. Behrakis • Alan Bressler • Jan Brett • Susan Bredhoff Cohen, ex-officio • Cynthia Curme • Alan J. Dworsky • William R. Elfers • Nancy J. Fitzpatrick • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Charles H. Jenkins, Jr. • Joyce G. Linde • John M. Loder • Carmine A. Martignetti • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. • Aaron J. Nurick, ex-officio • Susan W. Paine • Peter Palandjian, ex-officio • Carol Reich • Edward I. Rudman • Arthur I. Segel • Thomas G. Stemberg • Theresa M. Stone • Caroline Taylor • Stephen R. Weiner • Robert C. Winters Life Trustees Vernon R. Alden • Harlan E. Anderson • David B. Arnold, Jr. • J.P. Barger • Leo L. Beranek • Deborah Davis Berman • Peter A. Brooke • Helene R. Cahners • James F. Cleary† • John F. Cogan, Jr. • Mrs. Edith L. Dabney • Nelson J. Darling, Jr. • Nina L. Doggett • Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick • Dean W. Freed • Thelma E. Goldberg • Mrs. Béla T. Kalman • George Krupp • Mrs. Henrietta N. Meyer • Nathan R. Miller • Richard P. Morse • David Mugar • Mary S. Newman • William J. Poorvu • Irving W. Rabb† • Peter C. Read • Richard A. Smith • Ray Stata • John Hoyt Stookey • Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. • John L. Thorndike • Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas Other Officers of the Corporation Mark Volpe, Managing Director • Thomas D. -

Lista De Inscripciones Lista De Inscrições Entry List

LISTA DE INSCRIPCIONES La siguiente información, incluyendo los nombres específicos de las categorías, números de categorías y los números de votación, son confidenciales y propiedad de la Academia Latina de la Grabación. Esta información no podrá ser utilizada, divulgada, publicada o distribuída para ningún propósito. LISTA DE INSCRIÇÕES As sequintes informações, incluindo nomes específicos das categorias, o número de categorias e os números da votação, são confidenciais e direitos autorais pela Academia Latina de Gravação. Estas informações não podem ser utlizadas, divulgadas, publicadas ou distribuídas para qualquer finalidade. ENTRY LIST The following information, including specific category names, category numbers and balloting numbers, is confidential and proprietary information belonging to The Latin Recording Academy. Such information may not be used, disclosed, published or otherwise distributed for any purpose. REGLAS SOBRE LA SOLICITACION DE VOTOS Miembros de La Academia Latina de la Grabación, otros profesionales de la industria, y compañías disqueras no tienen prohibido promocionar sus lanzamientos durante la temporada de voto de los Latin GRAMMY®. Pero, a fin de proteger la integridad del proceso de votación y cuidar la información para ponerse en contacto con los Miembros, es crucial que las siguientes reglas sean entendidas y observadas. • La Academia Latina de la Grabación no divulga la información de contacto de sus Miembros. • Mientras comunicados de prensa y avisos del tipo “para su consideración” no están prohibidos, -

Beats of Your Town

BEATS OF YOUR TOWN On the eve of the release of their new album ‘Ocean’s Apart’, Grant McLennan, co-leader of watershed Brisbane pop group, The Go-Betweens, takes the time to grant Robiter an interview. Matthew ‘The Rock Lobbster’ Lobb reports The Clowns Come To Town – Film School Rejections and UQ Librarians Long before Queensland art tangled at a pretty summit with pop music (the years prior to LP wonderworks such as Before Hollywood, Liberty Belle And The Black Diamond Express and 16 Lovers Lane) , one Grant McLennan had been knocked back from film and television school on account of his 16 years. Enrolment in an arts program at the University of Queensland came, therefore, as a sort of edifying compromise. Once at St. Lucia, the undergraduate - a brainy eldest child from rural Queensland - befriended a gracefully mincing eccentric named Robert Forster who played guitar and wrote his own songs. The two bonded over shared tastes in skewered pop culture and spent a lot of time at the Humanities library reading, in import copies of The Village Voice, about emerging bands like Television and Talking Heads. Go-Betweens circa '78: Librarians Beware No doubt McLennan was more OCEAN’S APART PICKED APART Grant talks Robiter through the new studious than his pal who failed both at arts and at convincing him to album form a rock group. While a disciplined McLennan passed classes with focused endeavour, Forster was crashing heavily and channelling his ‘Here Comes A City’ (the first vigour into composing songs about would-be love interests. -

Hele Årboken (2.501Mb)

Redaktører: Eva Georgii-Hemming Sven-Erik Holgersen Øivind Varkøy Lauri Väkevä Nordisk musikkpedagogisk forskning Årbok 16 Nordic Research in Music Education Yearbook Vol. 16 NMH-publikasjoner 2015:8 Nordisk musikkpedagogisk forskning Årbok 16 Nordic Research in Music Education Yearbook Vol. 16 Redaksjon: Eva Georgii-Hemming Sven-Erik Holgersen Øivind Varkøy Lauri Väkevä NMH-publikasjoner 2015:8 Nordisk musikkpedagogisk forskning. Årbok 16 Nordic Research in Music Education. Yearbook Vol. 16 Redaktører: Eva Georgii-Hemming, Sven-Erik Holgersen, Øivind Varkøy og Lauri Väkevä Norges musikkhøgskole NMH-publikasjoner 2015:8 © Norges musikkhøgskole og forfatterne ISSN 1504-5021 ISBN 978-82-7853-208-9 Norges musikkhøgskole Postboks 5190 Majorstua 0302 OSLO Tel.: +47 23 36 70 00 E-post: [email protected] nmh.no Sats og trykk: 07 Media, Oslo, 2015 Contents Introduction 5 Musical Knowledge and Musical Bildung – 9 Jürgen Vogt Some Reflections on a Difficult Relation 23 the unheard On Heidegger’s relevance for a phenomenologically oriented music Didaktik: Frederik Pio Challenges to music education research. 53 Cecilia K. Hultberg Reflections from a Swedish perspective Gender Performativity through Musicking: 69 Examples from a Norwegian Classroom Study Silje Valde Onsrud Keeping it real: addressing authenticity in classroom popular music pedagogy 87 Aleksi Ojala & Lauri Väkevä “You MAY take the note home an’… well practise just that” – 101 Children’s interaction in contextualizing music teaching Tina Kullenberg & Monica Lindgren Young Instrumentalists’ -

Rückkopplungen Aus Dem Zodiak Free Arts Lab

BILDET NISCHEN! Rückkopplungen aus dem Zodiak Free Arts Lab HAU 21.–26.9.2021 Bildet Nischen! Rückkopplungen aus dem Zodiak Free Arts Lab 21.–26.9.2021 / HAU1 Im Winter des Jahres 1967 begann der Musiker und Künstler Conrad Schnitzler, auf Einladung des Wirtes Paul Glaser in zwei Räumen unter der damaligen Schaubühne am Halleschen Ufer, dem heutigen HAU2, das Programm zu gestalten. Mit Mit strei - ter:innen betrieb er das Zodiak Free Arts Lab über ein Jahr lang als hierarchiefreien Raum für musikalische Experimente und interdisziplinären Austausch. Bis 1969 diente das Zodiak als künstlerischer wie sozialer Treffpunkt. Trotz des kurzen Be- stehens kann es als initiierender Ort für zahlreiche musikalische Entwicklungen ver- standen werden – vor allem für die kurze Zeit später entstehende “Berliner Schule”, deren Sound oft unter dem Begriff “Krautrock” zusammengefasst wird und der bis heute in diversen musikalischen Strömungen nachhallt. “Bildet Nischen! Rückkopplungen aus dem Zodiak Free Arts Lab” begibt sich auf Spurensuche und beleuchtet die Verbindungen aus politischen, sozialen und kultu- rellen Verhältnissen, die auf die Szene um das Zodiak einwirkten. Welche Gemenge - lagen setzen auch heute noch Energien frei, die sich in (pop-)kulturellen Entwick- lungen manifestieren? Wie findet sich Gegenkultur und welcher Räume bedarf es dafür? Lassen sich Spuren und Bezüge des Zodiak in der kulturellen Praxis späterer subkultureller Entwicklungen im Berliner Underground aufzeigen? Fragestellungen wie diese bleiben bis in die aktuelle Gegenwart für die Entwicklung künstlerischer Positionen relevant. In einem Programm aus Konzerten, Kollaborationen, Installa- tionen, Gesprächen und einer Lecture Performance geht das HAU ihnen nach. Ein Festival des HAU Hebbel am Ufer. -

Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene

NIGHTLIGHT: TRADITION AND CHANGE IN A LOCAL MUSIC SCENE Aaron Smithers A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Curriculum of Folklore. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Glenn Hinson Patricia Sawin Michael Palm ©2018 Aaron Smithers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Aaron Smithers: Nightlight: Tradition and Change in a Local Music Scene (Under the direction of Glenn Hinson) This thesis considers how tradition—as a dynamic process—is crucial to the development, maintenance, and dissolution of the complex networks of relations that make up local music communities. Using the concept of “scene” as a frame, this ethnographic project engages with participants in a contemporary music scene shaped by a tradition of experimentation that embraces discontinuity and celebrates change. This tradition is learned and communicated through performance and social interaction between participants connected through the Nightlight—a music venue in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Any merit of this ethnography reflects the commitment of a broad community of dedicated individuals who willingly contributed their time, thoughts, voices, and support to make this project complete. I am most grateful to my collaborators and consultants, Michele Arazano, Robert Biggers, Dave Cantwell, Grayson Currin, Lauren Ford, Anne Gomez, David Harper, Chuck Johnson, Kelly Kress, Ryan Martin, Alexis Mastromichalis, Heather McEntire, Mike Nutt, Katie O’Neil, “Crowmeat” Bob Pence, Charlie St. Clair, and Isaac Trogden, as well as all the other musicians, employees, artists, and compatriots of Nightlight whose combined efforts create the unique community that define a scene. -

“Just a Dream”: Community, Identity, and the Blues of Big Bill Broonzy. (2011) Directed by Dr

GREENE, KEVIN D., Ph.D. “Just a Dream”: Community, Identity, and the Blues of Big Bill Broonzy. (2011) Directed by Dr. Benjamin Filene. 332 pgs This dissertation investigates the development of African American identity and blues culture in the United States and Europe from the 1920s to the 1950s through an examination of the life of one of the blues’ greatest artists. Across his career, Big Bill Broonzy negotiated identities and formed communities through exchanges with and among his African American, white American, and European audiences. Each respective group held its own ideas about what the blues, its performers, and the communities they built meant to American and European culture. This study argues that Broonzy negotiated a successful and lengthy career by navigating each groups’ cultural expectations through a process that continually transformed his musical and professional identity. Chapter 1 traces Broonzy’s negotiation of black Chicago. It explores how he created his new identity and contributed to the flowering of Chicago’s blues community by navigating the emerging racial, social, and economic terrain of the city. Chapter 2 considers Broonzy’s music career from the early twentieth century to the early 1950s and argues that his evolution as a musician—his lifelong transition from country fiddler to solo male blues artist to black pop artist to American folk revivalist and European jazz hero—provides a fascinating lens through which to view how twentieth century African American artists faced opportunities—and pressures—to reshape their identities. Chapter 3 extends this examination of Broonzy’s career from 1951 until his death in 1957, a period in which he achieved newfound fame among folklorists in the United States and jazz and blues aficionados in Europe. -

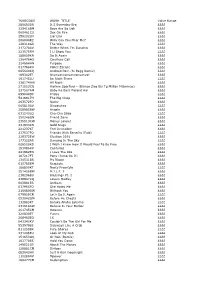

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

Catálogo General De Popurris Actualizado En Septiembre 2021

RICKYCORREO - CATÁLOGO GENERAL DE POPURRIS ACTUALIZADO EN SEPTIEMBRE 2021 Ref : 0033 Título: Bolero Mix M F DÚO INSTR Intérprete: Rickycorreo Precio: 12 € Contenido del Popurri: Cuenta conmigo El Reloj Solamente una vez Quizas Quizas Ref : 0059 Título: Popurri Sudamericano M F DÚO INSTR Intérprete: Orquesta Maravella Precio: 6 € Contenido del Popurri: La media vuelta María Bonita Los altos de Jalisco Cielito lindo Ref : 0203 Título: Popurri Julio Iglesias M F DÚO INSTR Intérprete: Version Rickycorreo Precio: 12 € Contenido del Popurri: Paloma Blanca Bamboleo Milonga sentimental Agua dulce, agua salá Torero Baila morena Una lágrima Me va Ref : 0209 Título: Cumbias Mix M F DÚO INSTR Intérprete: Tropicana Club Precio: 6 € Contenido del Popurri: Pollera Colorá Mama no puedo con ella Anoche soñe contigo Adiós adiós corazón Momposina Ref : 0220 Título: Popurri Latino M F DÚO INSTR Intérprete: Julio Iglesias Precio: 12 € Contenido del Popurri: Tres palabras Perfidia Amapola Noche De Ronda Quizás, Quizás Manisero Ref : 0229 Título: Rumboleros 2 M F DÚO INSTR Intérprete: Camino Real Precio: 10 € Contenido del Popurri: La Barca Esta Tarde Ví LLover Perfidia Camino Verde María Dolores Ref : 0232 Título: Popurri Boleros 2 M F DÚO INSTR Intérprete: Version Rickycorreo Precio: 6 € Contenido del Popurri: El Reloj Perfidia Solamente una vez María Elena Ref : 0236 Título: Bamboleo M F DÚO INSTR Intérprete: Julio Iglesias Precio: 6 € Contenido del Popurri: Bamboleo Caballo Viejo Ref : 0326 Título: Popurri Los Manolos M F DÚO INSTR Intérprete: Version Rickycorreo -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Repertorio Tartara Clasif 2016

TARTARA SONG LIST ENGLISH MUSIC Artist Song ABBA Dancing Queen ACDC You Shook Me All Night Long All of me John Legend Aqua Barbie Girl Aretha Franklin Respect Arianna Grande Break Free Armin Van Buuren Going Wrong Avicci Wake Me Up Avril Lavigne Girlfriend Backstreet Boys Just Want You to Know Becky G Can´t Stop Dancing Bee Gees Saturday Night Fever Bee Gees Stayin Alive Bee Gees Bee Gees Medley Bill Haley & His comets Rock Around the Clock Billy Idol Dancing with Myself Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Black Eyed Peas The Time Bon Jovi It's My Life Bruno Mars Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars Up Town Funk Calvin Harris Feel So Close Calvin Harris Summer Calvin Harris How deep is your love Calvin Harris Sweet Nothing Carl Perkins Blue Suede Shoes Cher Believe Chuck Berry Johnny B Good Cindy Lauper Girls Just Wanna Have Fun Clean Bandit Rather Be Cold Play A Sky Full of Stars Come Fly With Me Michael Bubble Daft Punk Get Lucky Dave Clark Five Do You Love Me (Now That I Can Dance) David Getta Titanium David Getta Without you David Guetta & Chriss Willis Love Is Gone David Guetta Ft. Akon Sexy Bitch Diana Ross - Rupaul I will survive Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud Edward Maya Stereo Love Elvis Presley Have Some Fun Tonight Elvis Presley Jailhouse Rock Elvis Presley Tutti Frutti Elvis Presley Blue Suede Shoes Endless Love Diana Ross & Lionel Riche Enrique Iglesias I Like It Enrique Iglesias Tonight I´Loving You Farrel Williams Happy Farruko Secretos Flo Rida Club Can't Handle Me Frank Sinatra Come fly With Me Frank Sinatra My way Frank Sinatra