Music and Spirituality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

The Influence of Characteristics on Music Enjoyment and Preference

Page 12 Oshkosh Scholar The Influence of Characteristics on Music Enjoyment and Preference Kristie Wirth, author Dr. Quin Chrobak, Psychology, faculty mentor Kristie Wirth is a senior at UW Oshkosh studying psychology and French. She plans to pursue a Ph.D. in counseling psychology after graduating. Her ideal career would involve both teaching and counseling at a university. She conducted the following research study as part of the McNair Scholars Program during spring 2012. Dr. Quin Chrobak received his B.A. from Drew University, his M.A. from American University, and his Ph.D. in experimental psychology from Kent State University. His research focuses on understanding how memory and cognition operate in complex real-world situations. Most recently, his research has begun to explore the notion that the nature of the relationship between witnessed and suggested/fabricated events may contribute to the false memory development. Abstract Past research has indicated that two specific personality traits, openness and empathy, may contribute to greater enjoyment of music that expresses negative emotions. Individuals with elevated levels of depressive symptoms may similarly have a preference for negative music. However, no research to date has explored the impact of both personality traits and depressive symptoms in the same investigation. The current study measured both music enjoyment (how much people like certain music) and music preference (how often people choose to listen to certain music) after exposure to negative, neutral, and positive music. Supporting prior research, this study indicated that individuals high in overall empathy (the ability to experience the emotions of another) had a greater enjoyment of negative emotional music. -

In Canto XXV of the Purgatorio, Statius' Exposition on The

1-Ureni:0Syrimis 1/19/11 3:20 PM Page 9 HUMAN GENERATION , M EMORY AND POETIC CREATION : FROM THE PURGATORIO TO THE PARADISO PAOLA URENI Summary : Statius’ scientific digression on the generation of the fetus and the formation of the fictive body in the afterlife occupies a large part of canto XXV of Dante’s Purgatorio . This article will examine the metaphorical relevance of that technical exposition to Dante’s poetics. The analogy between procreation and poetic creation appears to be con - sistent once the scientific lesson on embryology of canto XXV is under - stood as mirroring the definition of the Dolce Stil Novo offered by Dante in the previous canto ( Purg. XXIV). The second part of this article stress - es the importance of cantos XXIV and XXV as an authorization to inves - tigate the presence, in Dante’s Comedy , of a particular notion of purely rational memory derived from Augustine’s speculation. The allusion to an Augustinian conception of memory in Purgatorio XXV opens the pos - sibility of considering its presence in the precisely intellectual dimension of Paradiso . In canto XXV of the Purgatorio , Statius’ exposition on the generation of the fetus and the formation of the fictive body in the afterlife is evidence not only of Dante’s awareness of the medical debates of his time, but also of his willingness to enter into such discussion. Less obvious, but perhaps more important is this technical exposition’s metaphorical relevance to Dante’s poetics. The analysis of the relation between human generation and poetic inspiration is the focus of the first part of this article. -

December-4-2016-Bulletin-1

They will not hurt or destroy on all my holy mountain; for the earth will be full of the knowledge of the LORD as the waters cover the sea. Isaiah 11:9 St. John Evangelical Lutheran Church Second Sunday of Advent – December 4, 2016 420 Beaver Street PO Box 411 Mars, PA 16046-0411 www.stjohnchurchmars.org Phone: 724-625-1830 email: [email protected] Pastor‟s cell: 412-585-1628 Pastor‟s email: [email protected] Rev. Robert Zimmerman, Pastor Jacob Gordon, Director of Music Ministries We welcome you to St. John Lutheran Church. We are delighted to have you worship with us this morning. Should you have no permanent church-home in this community, why not consider making this one your own? Please sign the guest book as you leave worship today. You are most welcome here at St. John! Most elements of our service can be found in the bulletin, everything else is in the hymnal. Page refers to the numbered pages towards the front of the hymnal, hymns are bold and towards the back. Please rise when there is an *, congregational responses are in bold, and underlined elements of the service are found in the hymnal. LESSONS & CAROLS WITH HOLY COMMUNION Second Sunday of Advent – December 4, 2016 This morning, Lessons and Carols take the place of our usual three Scripture readings and sermon. The pattern of the traditional lessons and carols service, which traces its roots to Christmas Eve 1918 at King‟s College, Cambridge, England (though that service had its roots in older, monastic services). -

The Slow Integration of Instruments Into Christian Worship

Musical Offerings Volume 8 Number 1 Spring 2017 Article 2 3-28-2017 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Jonathan M. Lyons Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings Part of the Christianity Commons, Fine Arts Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Musicology Commons, and the Music Performance Commons DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Recommended Citation Lyons, Jonathan M. (2017) "From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship," Musical Offerings: Vol. 8 : No. 1 , Article 2. DOI: 10.15385/jmo.2017.8.1.2 Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/musicalofferings/vol8/iss1/2 From Silence to Golden: The Slow Integration of Instruments into Christian Worship Document Type Article Abstract The Christian church’s stance on the use of instruments in sacred music shifted through influences of church leaders, composers, and secular culture. Synthesizing the writings of early church leaders and church historians reveals a clear progression. The early musical practices of the church were connected to the Jewish synagogues. As recorded in the Old Testament, Jewish worship included instruments as assigned by one’s priestly tribe. -

Music for Contemporary Christians: What, Where, and When?

Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 13/1 (Spring 2002): 184Ð209. Article copyright © 2002 by Ed Christian. Music for Contemporary Christians: What, Where, and When? Ed Christian Kutztown University of Pennsylvania What music is appropriate for Christians? What music is appropriate in worship? Is there a difference between music appropriate in church and music appropriate in a youth rally or concert? Is there a difference between lyrics ap- propriate for congregational singing and lyrics appropriate for a person to sing or listen to in private? Are some types of music inherently inappropriate for evangelism?1 These are important questions. Congregations have fought over them and even split over them.2 The answers given have often alienated young people from the church and even driven them to reject God. Some answers have rejuve- nated congregations; others have robbed congregations of vitality and shackled the work of the Holy Spirit. In some churches the great old hymns havenÕt been heard in years. Other churches came late to the Òpraise musicÓ wars, and music is still a controversial topic. Here, where praise music is found in the church service, it is probably accompanied by a single guitar or piano and sung without a trace of the enthusi- asm, joy, emotion, and repetition one hears when it is used in charismatic churches. Many churches prefer to use no praise choruses during the church service, some use nothing but praise choruses, and perhaps the majority use a mixture. What I call (with a grin) Òrock ÔnÕ roll church,Ó where such instruments 1 Those who have recently read my article ÒThe Christian & Rock Music: A Review-Essay,Ó may turn at once to the section headed ÒThe Scriptural Basis.Ó Those who havenÕt read it should read on. -

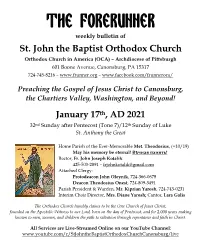

The Forerunner

The Forerunner weekly bulletin of St. John the Baptist Orthodox Church Orthodox Church in America (OCA) – Archdiocese of Pittsburgh 601 Boone Avenue, Canonsburg, PA 15317 724-745-8216 – www.frunner.org – www.facebook.com/frunneroca/ Preaching the Gospel of Jesus Christ to Canonsburg, the Chartiers Valley, Washington, and Beyond! January 17th, AD 2021 32nd Sunday after Pentecost (Tone 7)/12th Sunday of Luke St. Anthony the Great Home Parish of the Ever-Memorable Met. Theodosius, (+10/19) May his memory be eternal! Вѣчная память! Rector, Fr. John Joseph Kotalik 425-503-2891 – [email protected] Attached Clergy: Protodeacon John Oleynik, 724-366-0678 Deacon Theodosius Onest, 724-809-3491 Parish President & Warden, Mr. Kiprian Yarosh, 724-743-0231 Interim Choir Director, Mrs. Diane Yarosh; Cantor, Lara Galis The Orthodox Church humbly claims to be the One Church of Jesus Christ, founded on the Apostolic Witness to our Lord, born on the day of Pentecost, and for 2,000 years making known to men, women, and children the path to salvation through repentance and faith in Christ. All Services are Live-Streamed Online on our YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/c/StJohntheBaptistOrthodoxChurchCanonsburg/live Upcoming Schedule January 19, Tuesday: -7:00 PM, All-OCA Online Church School for Middle and High School Students: Every Tuesday, go to https://www.oca.org/ocs and click your age group! January 21, Thursday: FR. JOHN & MAT. JANINE RETURNING January 23, Saturday: -5:15 PM, General Pannikhida -6:00 PM, Vespers & Confession January 24, Sunday (New Martyrs & Confessors of Russia; Xenia of Petersburg; Sanctity of Life Sunday): -8:45 – 9:15 AM, Confession -9:30 AM, Divine Liturgy Church Open Until Noon -6:00 PM, Moleben to St. -

Southern Black Gospel Music: Qualitative Look at Quartet Sound

LIBERTY UNIVERSITY SOUTHERN BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC: QUALITATIVE LOOK AT QUARTET SOUND DURING THE GOSPEL ‘BOOM’ PERIOD OF 1940-1960 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY BY BEATRICE IRENE PATE LYNCHBURG, V.A. April 2014 1 Abstract The purpose of this work is to identify features of southern black gospel music, and to highlight what makes the music unique. One goal is to present information about black gospel music and distinguishing the different definitions of gospel through various ages of gospel music. A historical accounting for the gospel music is necessary, to distinguish how the different definitions of gospel are from other forms of gospel music during different ages of gospel. The distinctions are important for understanding gospel music and the ‘Southern’ gospel music distinction. The quartet sound was the most popular form of music during the Golden Age of Gospel, a period in which there was significant growth of public consumption of Black gospel music, which was an explosion of black gospel culture, hence the term ‘gospel boom.’ The gospel boom period was from 1940 to 1960, right after the Great Depression, a period that also included World War II, and right before the Civil Rights Movement became a nationwide movement. This work will evaluate the quartet sound during the 1940’s, 50’s, and 60’s, which will provide a different definition for gospel music during that era. Using five black southern gospel quartets—The Dixie Hummingbirds, The Fairfield Four, The Golden Gate Quartet, The Soul Stirrers, and The Swan Silvertones—to define what southern black gospel music is, its components, and to identify important cultural elements of the music. -

Summer 2012 Boston Symphony Orchestra

boston symphony orchestra summer 2012 Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 131st season, 2011–2012 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Edmund Kelly, Chairman • Paul Buttenwieser, Vice-Chairman • Diddy Cullinane, Vice-Chairman • Stephen B. Kay, Vice-Chairman • Robert P. O’Block, Vice-Chairman • Roger T. Servison, Vice-Chairman • Stephen R. Weber, Vice-Chairman • Vincent M. O’Reilly, Treasurer William F. Achtmeyer • George D. Behrakis • Alan Bressler • Jan Brett • Susan Bredhoff Cohen, ex-officio • Cynthia Curme • Alan J. Dworsky • William R. Elfers • Nancy J. Fitzpatrick • Michael Gordon • Brent L. Henry • Charles H. Jenkins, Jr. • Joyce G. Linde • John M. Loder • Carmine A. Martignetti • Robert J. Mayer, M.D. • Aaron J. Nurick, ex-officio • Susan W. Paine • Peter Palandjian, ex-officio • Carol Reich • Edward I. Rudman • Arthur I. Segel • Thomas G. Stemberg • Theresa M. Stone • Caroline Taylor • Stephen R. Weiner • Robert C. Winters Life Trustees Vernon R. Alden • Harlan E. Anderson • David B. Arnold, Jr. • J.P. Barger • Leo L. Beranek • Deborah Davis Berman • Peter A. Brooke • Helene R. Cahners • James F. Cleary† • John F. Cogan, Jr. • Mrs. Edith L. Dabney • Nelson J. Darling, Jr. • Nina L. Doggett • Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick • Dean W. Freed • Thelma E. Goldberg • Mrs. Béla T. Kalman • George Krupp • Mrs. Henrietta N. Meyer • Nathan R. Miller • Richard P. Morse • David Mugar • Mary S. Newman • William J. Poorvu • Irving W. Rabb† • Peter C. Read • Richard A. Smith • Ray Stata • John Hoyt Stookey • Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. • John L. Thorndike • Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas Other Officers of the Corporation Mark Volpe, Managing Director • Thomas D. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Spirituality and Healthcare—Common Grounds for the Secular and Religious Worlds and Its Clinical Implications

religions Article Spirituality and Healthcare—Common Grounds for the Secular and Religious Worlds and Its Clinical Implications Marcelo Saad 1,* and Roberta de Medeiros 2 1 Spiritist-Medical Association of São Paulo, São Paulo, SP 04310-060, Brazil 2 Medicine School, Centro Universitário Lusíada, São Paulo, SP 11050-071, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The spiritual dimension of patients has progressively gained more relevance in healthcare in the last decades. However, the term “spiritual” is an open, fluid concept and, for health purposes, no definition of spirituality is universally accepted. Health professionals and researchers have the challenge to cover the entire spectrum of the spiritual level in their practice. This is particularly difficult because most healthcare courses do not prepare their graduates in this field. They also need to face acts of prejudice by their peers or their managers. Here, the authors aim to clarify some common grounds between secular and religious worlds in the realm of spirituality and healthcare. This is a conceptual manuscript based on the available scientific literature and on the authors’ experi- ence. The text explores the secular and religious intersection involving spirituality and healthcare, together with the common ground shared by the two fields, and consequent clinical implications. Summarisations presented here can be a didactic beginning for practitioners or scholars involved in health or behavioural sciences. The authors think this construct can favour accepting the patient’s spiritual dimension importance by healthcare professionals, treatment institutes, and government policies. Keywords: religion; spirituality; humanism; healthcare; medicine; secularism; worldviews Citation: Saad, Marcelo, and Roberta de Medeiros. -

Classical Net Review

The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source BOOK REVIEW The Psychology of Music Diana Deutsch, editor Academic Press, Third Edition, 2013, pp xvii + 765 ISBN-10: 012381460X ISBN-13: 978-0123814609 The psychology of music was first explored in detail in modern times in a book of that name by Carl E. Seashore… Psychology Of Music was published in 1919. Dover's paperback edition of almost 450 pages (ISBN- 10: 0486218511; ISBN-13: 978-0486218519) is still in print from half a century later (1967) and remains a good starting point for those wishing to understand the relationship between our minds and music, chiefly as a series of physical processes. From the last quarter of the twentieth century onwards much research and many theories have changed the models we have of the mind when listening to or playing music. Changes in music itself, of course, have dictated that the nature of human interaction with it has grown. Unsurprisingly, books covering the subject have proliferated too. These range from examinations of how memory affects our experience of music through various forms of mental disabilities, therapies and deviations from "standard" auditory reception, to attempts to explain music appreciation psychologically. Donald Hodges' and David Conrad Sebald's Music in the Human Experience: An Introduction to Music Psychology (ISBN-10: 0415881862; ISBN-13: 978- 0415881869) makes a good introduction to the subject; while Aniruddh Patel's Music, Language, and the Brain (ISBN-10: 0199755302; ISBN-13: 978-0199755301) is a good (and now classic/reference) overview. Oliver Sacks' Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain (ISBN-10: 1400033535; ISBN-13: 978-1400033539) examines specific areas from a clinical perspective.