The GNOME Census: Who Writes GNOME?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Desktop Migration and Administration Guide

Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Desktop Migration and Administration Guide GNOME 3 desktop migration planning, deployment, configuration, and administration in RHEL 7 Last Updated: 2021-05-05 Red Hat Enterprise Linux 7 Desktop Migration and Administration Guide GNOME 3 desktop migration planning, deployment, configuration, and administration in RHEL 7 Marie Doleželová Red Hat Customer Content Services [email protected] Petr Kovář Red Hat Customer Content Services [email protected] Jana Heves Red Hat Customer Content Services Legal Notice Copyright © 2018 Red Hat, Inc. This document is licensed by Red Hat under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. If you distribute this document, or a modified version of it, you must provide attribution to Red Hat, Inc. and provide a link to the original. If the document is modified, all Red Hat trademarks must be removed. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, the Red Hat logo, JBoss, OpenShift, Fedora, the Infinity logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. Linux ® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java ® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS ® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL ® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. -

Ubuntu Kung Fu

Prepared exclusively for Alison Tyler Download at Boykma.Com What readers are saying about Ubuntu Kung Fu Ubuntu Kung Fu is excellent. The tips are fun and the hope of discov- ering hidden gems makes it a worthwhile task. John Southern Former editor of Linux Magazine I enjoyed Ubuntu Kung Fu and learned some new things. I would rec- ommend this book—nice tips and a lot of fun to be had. Carthik Sharma Creator of the Ubuntu Blog (http://ubuntu.wordpress.com) Wow! There are some great tips here! I have used Ubuntu since April 2005, starting with version 5.04. I found much in this book to inspire me and to teach me, and it answered lingering questions I didn’t know I had. The book is a good resource that I will gladly recommend to both newcomers and veteran users. Matthew Helmke Administrator, Ubuntu Forums Ubuntu Kung Fu is a fantastic compendium of useful, uncommon Ubuntu knowledge. Eric Hewitt Consultant, LiveLogic, LLC Prepared exclusively for Alison Tyler Download at Boykma.Com Ubuntu Kung Fu Tips, Tricks, Hints, and Hacks Keir Thomas The Pragmatic Bookshelf Raleigh, North Carolina Dallas, Texas Prepared exclusively for Alison Tyler Download at Boykma.Com Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their prod- ucts are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters or in all capitals. The Pragmatic Starter Kit, The Pragmatic Programmer, Pragmatic Programming, Pragmatic Bookshelf and the linking g device are trademarks of The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC. -

Communication Between Desktop and Web Applications

Communication between desktop and web applications Author: Manuel Rego Casasnovas Contact: [email protected] Date: 20/11/2009 Copyright: Some rights reserved. This document is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 licence, available in http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. Abstract: Nowadays, everybody uses web applications. Despite of their advantages, like being available at any place with Internet, they have some usability problems with regard to common desktop applications. This article tries to analyze the possible solutions in order to interconnect desktop and web applications, centered in the GNOME platform and using RTM-GLib as example and study case. Table of Contents Introduction 2 State of the art in the GNOME platform . .2 Goals .......................................7 The library: RTM-GLib 7 Dependencies . .7 Development . .8 License ......................................8 Roadmap . .8 Usage example . .9 Future ideas 9 Mojito.......................................9 Trackerminer................................... 10 EDSbackend................................... 11 Conclusion 11 1 Introduction There are a large amount of web services in the Internet. A general definition of web service said that it is a system which provides an interface to allow interaction between machines over a network. As time passes more and more web applications provide some kind of API in order to access their services. This number is growing and it seems that will keep growing for some time. Some examples of these applications: Flickr, Facebook, Twitter, etc. Web applications has some advantages compared with desktop applications: All the data is shared and in a centralized place. They do not need any special configuration or installation, just a simple web browser is enough. -

18 Free Ways to Download Any Video Off the Internet Posted on October 2, 2007 by Aseem Kishore Ads by Google

http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/18-free-ways-to-download-any-video-off-the-internet/ 18 Free Ways To Download Any Video off the Internet posted on October 2, 2007 by Aseem Kishore Ads by Google Download Videos Now download.cnet.com Get RealPlayer® & Download Videos from the web. 100% Secure Download. Full Movies For Free www.YouTube.com/BoxOffice Watch Full Length Movies on YouTube Box Office. Absolutely Free! HD Video Players from US www.20north.com/ Coby, TV, WD live, TiVo and more. Shipped from US to India Video Downloading www.VideoScavenger.com 100s of Video Clips with 1 Toolbar. Download Video Scavenger Today! It seems like everyone these days is downloading, watching, and sharing videos from video-sharing sites like YouTube, Google Video, MetaCafe, DailyMotion, Veoh, Break, and a ton of other similar sites. Whether you want to watch the video on your iPod while working out, insert it into a PowerPoint presentation to add some spice, or simply download a video before it’s removed, it’s quite essential to know how to download, convert, and play these videos. There are basically two ways to download videos off the Internet and that’s how I’ll split up this post: either via a web app or via a desktop application. Personally, I like the web applications better simply because you don’t have to clutter up and slow down your computer with all kinds of software! UPDATE: MakeUseOf put together an excellent list of the best websites for watching movies, TV shows, documentaries and standups online. -

Files: Cpan/Test-Harness/* Copyright: Copyright (C) 2007-2011

Files: cpan/Test-Harness/* Copyright: Copyright (c) 2007-2011, Andy Armstrong <[email protected]>. All rights reserved. License: GPL-1+ or Artistic Comment: This module is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the same terms as Perl itself. Files: cpan/Test-Harness/lib/TAP/Parser.pm Copyright: Copyright 2006-2008 Curtis "Ovid" Poe, all rights reserved. License: GPL-1+ or Artistic Comment: This program is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the same terms as Perl itself. Files: cpan/Test-Harness/lib/TAP/Parser/YAMLish/Reader.pm Copyright: Copyright 2007-2011 Andy Armstrong. Portions copyright 2006-2008 Adam Kennedy. License: GPL-1+ or Artistic Comment: This program is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the same terms as Perl itself. Files: cpan/Test-Simple/* Copyright: Copyright 2001-2008 by Michael G Schwern <[email protected]>. License: GPL-1+ or Artistic Comment: This program is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the same terms as Perl itself. Files: cpan/Test-Simple/lib/Test/Builder.pm Copyright: Copyright 2002-2008 by chromatic <[email protected]> and Michael G Schwern E<[email protected]>. License: GPL-1+ or Artistic 801 Comment: This program is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the same terms as Perl itself. Files: cpan/Test-Simple/lib/Test/Builder/Tester/Color.pm Copyright: Copyright Mark Fowler <[email protected]> 2002. License: GPL-1+ or Artistic Comment: This program is free software; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the same terms as Perl itself. -

1. D-Bus a D-Bus FAQ Szerint D-Bus Egy Interprocessz-Kommunikációs Protokoll, És Annak Referenciamegvalósítása

Az Udev / D-Bus rendszer - a modern asztali Linuxok alapja A D-Bus rendszer minden modern Linux disztribúcióban jelen van, sőt mára már a Linux, és más UNIX jellegű, sőt nem UNIX rendszerek (különösen a desktopon futó változatok) egyik legalapvetőbb technológiája, és az ismerete a rendszergazdák számára lehetővé tesz néhány rendkívül hasznos trükköt, az alkalmazásfejlesztőknek pedig egyszerűen KÖTELEZŐ ismerniük. Miért ilyen fontos a D-Bus? Mit csinál? D-Bus alapú technológiát teszik lehetővé többek között azt, hogy közönséges felhasználóként a kedvenc asztali környezetünkbe bejelentkezve olyan feladatokat hajtsunk végre, amiket a kernel csak a root felasználónak engedne meg. Felmountolunk egy USB meghajtót? NetworkManagerrel konfiguráljuk a WiFi-t, a 3G internetet vagy bármilyen más hálózati csatolót, és kapcsolódunk egy hálózathoz? Figyelmeztetést kapunk a rendszertől, hogy új szoftverfrissítések érkeztek, majd telepítjük ezeket? Hibernáljuk, felfüggesztjük a gépet? A legtöbb esetben ma már D-Bus alapú technológiát használunk ilyen esetben. A D-Bus lehetővé teszi, hogy egymástól függetlenül, jellemzően más UID alatt indított szoftverösszetevők szabványos és biztonságos módon igénybe vegyék egymás szolgáltatásait. Ha valaha lesz a Linuxhoz professzionális desktop tűzfal vagy vírusirtó megoldás, a dolgok jelenlegi állasa szerint annak is D- Bus technológiát kell használnia. A D-Bus technológia legfontosabb ihletője a KDE DCOP rendszere volt, és mára a D-Bus leváltotta a DCOP-ot, csakúgy, mint a Gnome Bonobo technológiáját. 1. D-Bus A D-Bus FAQ szerint D-Bus egy interprocessz-kommunikációs protokoll, és annak referenciamegvalósítása. Ezen referenciamegvalósítás egyik összetevője, a libdbus könyvtár a D- Bus szabványnak megfelelő kommunikáció megvalósítását segíti. Egy másik összetevő, a dbus- daemon a D-Bus üzenetek routolásáért, szórásáért felelős. -

Solaris 10 End of Life

Solaris 10 end of life Continue Oracle Solaris 10 has had an amazing OS update, including ground features such as zones (Solaris containers), FSS, Services, Dynamic Tracking (against live production operating systems without impact), and logical domains. These features have been imitated in the market (imitation is the best form of flattery!) like all good things, they have to come to an end. Sun Microsystems was acquired by Oracle and eventually, the largest OS known to the industry, needs to be updated. Oracle has set a retirement date of January 2021. Oracle indicated that Solaris 10 systems would need to raise support costs. Oracle has never provided migratory tools to facilitate migration from Solaris 10 to Solaris 11, so migration to Solaris has been slow. In September 2019, Oracle decided that extended support for Solaris 10 without an additional financial penalty would be delayed until 2024! Well its March 1 is just a reminder that Oracle Solaris 10 is getting the end of life regarding support if you accept extended support from Oracle. Combined with the fact gdpR should take effect on May 25, 2018 you want to make sure that you are either upgraded to Solaris 11.3 or have taken extended support to obtain any patches for security issues. For more information on tanningix releases and support dates of old and new follow this link ×Sestive to abort the Unix Error Operating System originally developed by Sun Microsystems SolarisDeveloperSun Microsystems (acquired by Oracle Corporation in 2009)Written inC, C'OSUnixWorking StateCurrentSource ModelMixedInitial release1992; 28 years ago (1992-06)Last release11.4 / August 28, 2018; 2 years ago (2018-08-28)Marketing targetServer, PlatformsCurrent: SPARC, x86-64 Former: IA-32, PowerPCKernel typeMonolithic with dynamically downloadable modulesDefault user interface GNOME-2-LicenseVariousOfficial websitewww.oracle.com/solaris Solaris is the own operating system Of Unix, originally developed by Sunsystems. -

An User & Developer Perspective on Immutable Oses

An User & Developer Perspective on Dario Faggioli Virtualization SW. Eng. @ SUSE Immutable OSes [email protected] dariof @DarioFaggioli https://dariofaggioli.wordpress.com/ https://about.me/dario.faggioli About Me What I do ● Virtualization Specialist Sw. Eng. @ SUSE since 2018, working on Xen, KVM, QEMU, mostly about performance related stuff ● Daily activities ⇒ how and what for I use my workstation ○ Read and send emails (Evolution, git-send-email, stg mail, ...) ○ Write, build & test code (Xen, KVM, Libvirt, QEMU) ○ Work with the Open Build Service (OBS) ○ Browse Web ○ Test OSes in VMs ○ Meetings / Video calls / Online conferences ○ Chat, work and personal ○ Some 3D Printing ○ Occasionally play games ○ Occasional video-editing ○ Maybe scan / print some document 2 ● Can all of the above be done with an immutable OS ? Immutable OS: What ? Either: ● An OS that you cannot modify Or, at least: ● An OS that you will have an hard time modifying What do you mean “modify” ? ● E.g., installing packages ● ⇒ An OS on which you cannot install packages ● ⇒ An OS on which you will have an hard time installing packages 3 Immutable OS: What ? Seriously? 4 Immutable OS: Why ? Because it will stay clean and hard to break ● Does this sound familiar? ○ Let’s install foo, and it’s dependency, libfoobar_1 ○ Let’s install bar (depends from libfoobar_1, we have it already) ○ Actually, let’s add an external repo. It has libfoobar_2 that makes foo work better! ○ Oh no... libfoobar_2 would break bar!! ● Yeah. It happens. Even in the best families distros -

Release Notes for Fedora 15

Fedora 15 Release Notes Release Notes for Fedora 15 Edited by The Fedora Docs Team Copyright © 2011 Red Hat, Inc. and others. The text of and illustrations in this document are licensed by Red Hat under a Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license ("CC-BY-SA"). An explanation of CC-BY-SA is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/. The original authors of this document, and Red Hat, designate the Fedora Project as the "Attribution Party" for purposes of CC-BY-SA. In accordance with CC-BY-SA, if you distribute this document or an adaptation of it, you must provide the URL for the original version. Red Hat, as the licensor of this document, waives the right to enforce, and agrees not to assert, Section 4d of CC-BY-SA to the fullest extent permitted by applicable law. Red Hat, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, the Shadowman logo, JBoss, MetaMatrix, Fedora, the Infinity Logo, and RHCE are trademarks of Red Hat, Inc., registered in the United States and other countries. For guidelines on the permitted uses of the Fedora trademarks, refer to https:// fedoraproject.org/wiki/Legal:Trademark_guidelines. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds in the United States and other countries. Java® is a registered trademark of Oracle and/or its affiliates. XFS® is a trademark of Silicon Graphics International Corp. or its subsidiaries in the United States and/or other countries. MySQL® is a registered trademark of MySQL AB in the United States, the European Union and other countries. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. -

Misc Thesisdb Bythesissuperv

Honors Theses 2006 to August 2020 These records are for reference only and should not be used for an official record or count by major or thesis advisor. Contact the Honors office for official records. Honors Year of Student Student's Honors Major Thesis Title (with link to Digital Commons where available) Thesis Supervisor Thesis Supervisor's Department Graduation Accounting for Intangible Assets: Analysis of Policy Changes and Current Matthew Cesca 2010 Accounting Biggs,Stanley Accounting Reporting Breaking the Barrier- An Examination into the Current State of Professional Rebecca Curtis 2014 Accounting Biggs,Stanley Accounting Skepticism Implementation of IFRS Worldwide: Lessons Learned and Strategies for Helen Gunn 2011 Accounting Biggs,Stanley Accounting Success Jonathan Lukianuk 2012 Accounting The Impact of Disallowing the LIFO Inventory Method Biggs,Stanley Accounting Charles Price 2019 Accounting The Impact of Blockchain Technology on the Audit Process Brown,Stephen Accounting Rebecca Harms 2013 Accounting An Examination of Rollforward Differences in Tax Reserves Dunbar,Amy Accounting An Examination of Microsoft and Hewlett Packard Tax Avoidance Strategies Anne Jensen 2013 Accounting Dunbar,Amy Accounting and Related Financial Statement Disclosures Measuring Tax Aggressiveness after FIN 48: The Effect of Multinational Status, Audrey Manning 2012 Accounting Dunbar,Amy Accounting Multinational Size, and Disclosures Chelsey Nalaboff 2015 Accounting Tax Inversions: Comparing Corporate Characteristics of Inverted Firms Dunbar,Amy Accounting Jeffrey Peterson 2018 Accounting The Tax Implications of Owning a Professional Sports Franchise Dunbar,Amy Accounting Brittany Rogan 2015 Accounting A Creative Fix: The Persistent Inversion Problem Dunbar,Amy Accounting Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act: The Most Revolutionary Piece of Tax Szwakob Alexander 2015D Accounting Dunbar,Amy Accounting Legislation Since the Introduction of the Income Tax Prasant Venimadhavan 2011 Accounting A Proposal Against Book-Tax Conformity in the U.S. -

Dell™ Gigaos 6.5 Release Notes July 2015

Dell™ GigaOS 6.5 Release Notes July 2015 These release notes provide information about the Dell™ GigaOS release. • About Dell GigaOS 6.5 • System requirements • Product licensing • Third-party contributions • About Dell About Dell GigaOS 6.5 For complete product documentation, visit http://software.dell.com/support/. System requirements Not applicable. Product licensing Not applicable. Third-party contributions Source code is available for this component on http://opensource.dell.com/releases/Dell_Software. Dell will ship the source code to this component for a modest fee in response to a request emailed to [email protected]. This product contains the following third-party components. For third-party license information, go to http://software.dell.com/legal/license-agreements.aspx. Source code for components marked with an asterisk (*) is available at http://opensource.dell.com. Dell GigaOS 6.5 1 Release Notes Table 1. List of third-party contributions Component License or acknowledgment abyssinica-fonts 1.0 SIL Open Font License 1.1 ©2003-2013 SIL International, all rights reserved acl 2.2.49 GPL (GNU General Public License) 2.0 acpid 1.0.10 GPL (GNU General Public License) 2.0 alsa-lib 1.0.22 GNU Lesser General Public License 2.1 alsa-plugins 1.0.21 GNU Lesser General Public License 2.1 alsa-utils 1.0.22 GNU Lesser General Public License 2.1 at 3.1.10 GPL (GNU General Public License) 2.0 atk 1.30.0 LGPL (GNU Lesser General Public License) 2.1 attr 2.4.44 GPL (GNU General Public License) 2.0 audit 2.2 GPL (GNU General Public License) 2.0 authconfig 6.1.12 GPL (GNU General Public License) 2.0 avahi 0.6.25 GNU Lesser General Public License 2.1 b43-fwcutter 012 GNU General Public License 2.0 basesystem 10.0 GPL (GNU General Public License) 3 bash 4.1.2-15 GPL (GNU General Public License) 3 bc 1.06.95 GPL (GNU General Public License) 2.0 bind 9.8.2 ISC 1995-2011. -

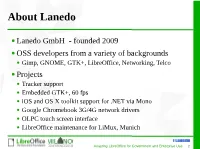

Libreoffice Presentation Template

About Lanedo ● Lanedo GmbH - founded 2009 ● OSS developers from a variety of backgrounds ● Gimp, GNOME, GTK+, LibreOffice, Networking, Telco ● Projects ● Tracker support ● Embedded GTK+, 60 fps ● iOS and OS X toolkit support for .NET via Mono ● Google Chromebook 3G/4G network drivers ● OLPC touch screen interface ● LibreOffice maintenance for LiMux, Munich Adapting LibreOffice for Government and Enterprise Use 2 Business Cases ● Two main cases: ● We're approached by business or governmental body ● We apply for government tenders ● Needs are analysed to form an estimate ● Predictable projects – fixed price ● Wider reaching projects – time and materials Adapting LibreOffice for Government and Enterprise Use 3 Business Cases - Examples ● Moonen Packaging ● Slow VLOOKUP across files ● Deliverable as a set of patches ● Google ● Additional modem support in ChromeOS ● ModemManager ● Weekly patches and weekly reports Adapting LibreOffice for Government and Enterprise Use 4 LibreOffice Projects at Lanedo ● Ink annotation support ● LibreOffice Impress kiosk mode ● Région Île-de-France ● LiMux – City of Munich ● PDF gradient support Adapting LibreOffice for Government and Enterprise Use 5 Ink Annotations ● SimplifyMD – software for electronic healthcare records Adapting LibreOffice for Government and Enterprise Use 6 Ink Annotations - Solution ● Added support in LibreOffice file import filters ● .docx and .rtf ● Analysed the errant files... ● Base 64 encoded blob indicates Ink feature ● Actual shape stored as VML path : <o:ink i="ANoFHQTeAqoDASAAaAwAAAAAAMAAAAAAAABGWM9UiuaXxU