Chemistry of Superheavy Elements: New Vistas for Studying Effects of Einstein's Relativity on the Structure of the Periodic Table

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

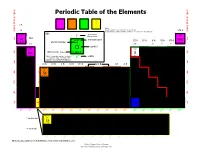

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

Atomic Properties of the Elements

P E R I O D I C T A B L E Group 1 18 IA Atomic Properties of the Elements VIIIA 2 1 S FREQUENTLY USED FUNDAMENTAL PHYSICAL CONSTANTS§ S 1 1/2 Physical Measurement Laboratory www.nist.gov/pml 2 0 1 second = 9 192 631 770 periods of radiation corresponding to the H transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of 133Cs Standard Reference Data www.nist.gov/srd He 1 Hydrogen −1 § For the most accurate Helium speed of light in vacuum c 299 792 458 m s (exact) values of these and 1.008* −34 4.002602 2 1s 2 Planck constant h 6.626 070 x 10 J s ( ħ /2 ) other constants, visit 13 14 15 16 17 1s −19 13.5984 IIA elementary charge e 1.602 177 x 10 C physics.nist.gov/constants IIIA IVA VA VIA VIIA 24.5874 −31 2 1 electron mass me 9.109 384 x 10 kg 2 3 4 3 2 1 3 S1/2 4 S0 2 5 P°1/2 6 P0 7 S3/2° 8 P2 9 P3/2° 10 S0 mec 0.510 999 MeV −27 Solids Li Be proton mass mp 1.672 622 x 10 kg B C N O F Ne 2 Lithium Beryllium fine-structure constant 1/137.035 999 Liquids Boron Carbon Nitrogen Oxygen Fluorine Neon 6.94* 9.0121831 −1 10.81* 12.011* 14.007* 15.999* 18.99840316* 20.1797 Rydberg constant R 10 973 731.569 m 2 2 2 Gases 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 2 2 4 2 2 5 2 2 6 15 1s 2s 2p 1s 2s 1s 2s 1s 2s 1s 2s 1s 2s 1s 2s R c 3.289 841 960 x 10 Hz 2p 2p 1s 2s 2p 2p 2p 5.3917 9.3227 Artificially 8.2980 11.2603 14.5341 13.6181 17.4228 21.5645 R hc 13.605 693 eV 2 1 -19 Prepared 2 3 4 3 2 1 11 S1/2 12 S0 electron volt eV 1.602 176 6 x 10 J 13 P1/2° 14 P0 15 S3/2° 16 P2 17 P3/2° 18 S0 −23 −1 Boltzmann constant k 1.380 65 x 10 J K −1 −1 Na Mg molar gas constant -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

Upper Limit of the Periodic Table and the Future Superheavy Elements

CLASSROOM Rajarshi Ghosh Upper Limit of the Periodic Table and the Future Department of Chemistry The University of Burdwan ∗ Superheavy Elements Burdwan 713 104, India. Email: [email protected] Controversy surrounds the isolation and stability of the fu- ture transactinoid elements (after oganesson) in the periodic table. A single conclusion has not yet been drawn for the highest possible atomic number, though there are several the- oretical as well as experimental results regarding this. In this article, the scientific backgrounds of those upcoming super- heavy elements (SHE) and their proposed electronic charac- ters are briefly described. Introduction Totally 118 elements, starting from hydrogen (atomic number 1) to oganesson (atomic number 118) are accommodated in the mod- ern form of the periodic table comprising seven periods and eigh- teen groups. Total 92 natural elements (if technetium is consid- ered as natural) are there in the periodic table (up to uranium hav- ing atomic number 92). In the actinoid series, only four elements— Keywords actinium, thorium, protactinium and uranium—are natural. The Superheavy elements, actinoid rest of the eleven elements—from neptunium (atomic number 93) series, transactinoid elements, periodic table. to lawrencium (atomic number 103)—are synthetic. Elements after actinoids (i.e., from rutherfordium) are called transactinoid elements. These are also called superheavy elements (SHE) as they have very high atomic numbers. Prof. G T Seaborg had Elements after actinoids a very distinct contribution in the field of transuranium element (i.e., from synthesis. For this, Prof. Seaborg was awarded the Nobel Prize in rutherfordium) are called transactinoid elements. 1951. -

Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2015 Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants John Dustin Despotopulos University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Chemistry Commons Repository Citation Despotopulos, John Dustin, "Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants" (2015). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2345. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7645877 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVESTIGATION OF FLEROVIUM AND ELEMENT 115 HOMOLOGS WITH MACROCYCLIC EXTRACTANTS By John Dustin Despotopulos Bachelor of Science in Chemistry University of Oregon 2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy -

The Elements.Pdf

A Periodic Table of the Elements at Los Alamos National Laboratory Los Alamos National Laboratory's Chemistry Division Presents Periodic Table of the Elements A Resource for Elementary, Middle School, and High School Students Click an element for more information: Group** Period 1 18 IA VIIIA 1A 8A 1 2 13 14 15 16 17 2 1 H IIA IIIA IVA VA VIAVIIA He 1.008 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 7A 4.003 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 Li Be B C N O F Ne 6.941 9.012 10.81 12.01 14.01 16.00 19.00 20.18 11 12 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 3 Na Mg IIIB IVB VB VIB VIIB ------- VIII IB IIB Al Si P S Cl Ar 22.99 24.31 3B 4B 5B 6B 7B ------- 1B 2B 26.98 28.09 30.97 32.07 35.45 39.95 ------- 8 ------- 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 4 K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr 39.10 40.08 44.96 47.88 50.94 52.00 54.94 55.85 58.47 58.69 63.55 65.39 69.72 72.59 74.92 78.96 79.90 83.80 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 5 Rb Sr Y Zr NbMo Tc Ru Rh PdAgCd In Sn Sb Te I Xe 85.47 87.62 88.91 91.22 92.91 95.94 (98) 101.1 102.9 106.4 107.9 112.4 114.8 118.7 121.8 127.6 126.9 131.3 55 56 57 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 6 Cs Ba La* Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt AuHg Tl Pb Bi Po At Rn 132.9 137.3 138.9 178.5 180.9 183.9 186.2 190.2 190.2 195.1 197.0 200.5 204.4 207.2 209.0 (210) (210) (222) 87 88 89 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 114 116 118 7 Fr Ra Ac~RfDb Sg Bh Hs Mt --- --- --- --- --- --- (223) (226) (227) (257) (260) (263) (262) (265) (266) () () () () () () http://pearl1.lanl.gov/periodic/ (1 of 3) [5/17/2001 4:06:20 PM] A Periodic Table of the Elements at Los Alamos National Laboratory 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 Lanthanide Series* Ce Pr NdPmSm Eu Gd TbDyHo Er TmYbLu 140.1 140.9 144.2 (147) 150.4 152.0 157.3 158.9 162.5 164.9 167.3 168.9 173.0 175.0 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 Actinide Series~ Th Pa U Np Pu AmCmBk Cf Es FmMdNo Lr 232.0 (231) (238) (237) (242) (243) (247) (247) (249) (254) (253) (256) (254) (257) ** Groups are noted by 3 notation conventions. -

Synthesis of Superheavy Elements by Cold Fusion

Radiochim. Acta 99, 405–428 (2011) / DOI 10.1524/ract.2011.1854 © by Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, München Synthesis of superheavy elements by cold fusion By S. Hofmann1,2,∗ 1 GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany 2 Institut für Kernphysik, Goethe-Universität, Max von Laue-Straße 1, 60438 Frankfurt, Germany (Received February 3, 2011; accepted in revised form April 18, 2011) Superheavy elements / Synthesis / Cold fusion / in 1972, and the RILAC (variable-frequency linear acceler- Cross-sections / Decay properties / Recoil separators / ator) at the RIKEN Nishina Center in Saitama near Tokio in Detector systems 1980. In the middle of the 1960s the concept of the macrosco- pic-microscopic model for calculating binding energies Summary. The new elements from Z = 107 to 112 were of nuclei also at large deformations was invented by synthesized in cold fusion reactions based on targets of lead V. M. Strutinsky [3]. Using this method, a number of the and bismuth. The principle physical concepts are presented measured phenomena could be naturally explained by con- which led to the application of this reaction type in search sidering the change of binding energy as function of defor- experiments for new elements. Described are the technical mation. In particular, it became possible now to calculate the developments from early mechanical devices to experiments with recoil separators. An overview is given of present ex- binding energy of a heavy fissioning nucleus at each point of periments which use cold fusion for systematic studies and the fission path and thus to determine the fission barrier. synthesis of new isotopes. -

History of the Seaborg Institute

HISTORY OF THE SEABORG INSTITUTE ARQ.2_09.cover.indd 1 6/22/09 9:24 AM ContentsContents History of the Seaborg Institute The Seaborg Institute for Transactinium Science Established to educate the next generation of nuclear scientists 1 ITS Advisory Council 5 Seaborg the scientist 7 Naming seaborgium 11 Branching out 13 IGCAR honors Seaborg’s contributions to actinide science 16 Seaborg Institute for Transactinium Science/Los Alamos National Laboratory Actinide Research Quarterly The Seaborg Institute for Transactinium Science Established to educate the next generation of nuclear scientists In the late 1970s and early 1980s, research opportunities in heavy element This article was contributed by science and engineering were seldom found in university settings, and the supply Darleane C. Hoffman, professor emerita, of professionals in those fields was diminishing to the detriment of national Graduate School, Department of goals. In response to these concerns, national studies were conducted and panels Chemistry, UC Berkeley, faculty senior and committees were formed to assess the status of training and education in the scientist, Lawrence Berkeley National nuclear sciences. The studies in particular addressed the future need for scientists Laboratory, and charter director, Seaborg trained in the areas of nuclear waste management and disposal, environmental Institute, Lawrence Livermore National remediation, nuclear fuel processing, and nuclear safety analysis. Laboratory; and Christopher Gatrousis, Unfortunately, with the exception of the American Chemical Society’s former associate director of Chemistry Division of Nuclear Chemistry and Technology summer schools for undergradu- and Materials Science, Lawrence ates in nuclear and radiochemistry established in 1984, the studies did not lead Livermore National Laboratory. -

Experimental Search for Superheavy Elements

THE HENRYK NIEWODNICZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF NUCLEAR PHYSICS POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES UL. RADZIKOWSKIEGO, 31-342 KRAKÓW, POLAND WWW.IFJ.EDU.PL/PUBL/REPORTS/2008/ KRAKÓW, DECEMBER 2008 REPORT No. 2019/PL Experimental search for superheavy elements Andrzej Wieloch* Habilitation thesis (prepared in March 2008) *M. Smoluchowski Institute of Physics, Jagiellonian University. Reymonta 4. 30-059 Kraków, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This work reports on the experimental search for superheavy elements (SHE). Two types of approaches for SHE production are studied i.e.: "cold" fusion mech anism and massive transfer mechanism. First mechanism was studied, in normal and inverse kinematics, by using Wien filter at the GANIL facility. The production of elements with Z=106 and 108 is reported while negative result on the synthesis of SHE elements with Z=114 and 118 was received. The other approach i.e. re actions induced by heavy ion projectiles (e.g.:172Yb. 197Au) on fissile target nuclei (e.g.: 2S8U., 2S2Th) at near Coulomb barrier incident energies was studied by using superconducting solenoid installed in Texas A&M University. Preliminary results for the reaction 197 Au(7.5MeV/u) -f 232Th are presented where three cases of the possible candidates for SHE elements were found. A dedicated detection setup for such studies is discussed and the detailed data analysis is presented. Detection of al pha and spontaneous fission radioactive decays is used to unambiguously identify the atomic number of SHE. Special statistical analysis for a very low detected number of a decays is applied to check consistency of the a radioactive chains. -

A Table of Frequently Used Radioisotopes

323 A Table of Frequently Used Radioisotopes Only decays with the largest branching fractions are listed. For β emitters the maximum energies of the continuous β-ray spectra are given. ‘→’ denotes the decay to the subsequent element in the ta- ble. EC stands for ‘electron capture’, a (= annus, Latin) for years, h for hours, d for days, min for minutes, s for seconds, and ms for milliseconds. isotope decay half- β resp. α γ energy A Z element type life energy (MeV) (MeV) 3 β− . γ 1H 12 3a 0.0186 no 7 γ 4Be EC, 53 d – 0.48 10 β− . × 6 γ 4Be 1 5 10 a 0.56 no 14 β− γ 6C 5730 a 0.156 no 22 β+ . 11Na ,EC 2 6a 0.54 1.28 24 β− γ . 11Na , 15 0h 1.39 1.37 26 β+ . × 5 13Al ,EC 7 17 10 a 1.16 1.84 32 β− γ 14Si 172 a 0.20 no 32 β− . γ 15P 14 2d 1.71 no 37 γ 18Ar EC 35 d – no 40 β− . × 9 19K ,EC 1 28 10 a 1.33 1.46 51 γ . 24Cr EC, 27 8d – 0.325 54 γ 25Mn EC, 312 d – 0.84 55 . 26Fe EC 2 73 a – 0.006 57 γ 27Co EC, 272 d – 0.122 60 β− γ . 27Co , 5 27 a 0.32 1.17 & 1.33 66 β+ γ . 31Ga , EC, 9 4h 4.15 1.04 68 β− γ 31Ga , EC, 68 min 1.88 1.07 85 β− γ . -

S D F P Periodic Table of the Elements O

shells (energy levels) (energy shells Periodic Table of the Elements levels) (energy shells I A s d p f subshell subshell subshell subshell Note: 1+ Atomic number = # of protons = # of electrons VIII A Atomic mass (rounded to nearest integer) = # of protons + # of neutrons hydrogen KEY most common helium 1 2- oxidation number 2 1 II A 1 H oxygen element name III A IV A V A VI A VII A He 1.00794(7) atomic number 8 4.002602(2) 2+ 3+ 3- 2- 1- symbol lithium beryllium O boron carbon nitrogen oxygen fluorine neon 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2 Li Be 2001 atomic mass 15.9994(3) B C N O F Ne 2 6.941(2) 9.012182(3) Note: The last significant figure is reliable to 4 orbital 10.811(7) 12.0107(8) 14.00674(7) 15.9994(3) 18.9984032(5) 20.1797(6) sodium magnesium +-1 except where greater uncertainty is given p aluminium silicon phosphorus sulfur chlorine argon 11 12 in parentheses ( ). Mass numbers given in 13 3+ 14 15 16 17 18 3 brackets [ ] are of the longest lived isotopes. 3 Na Mg III B IV B V B VI B VII B VIII B I B II B Al Si P S Cl Ar 22.989770(2) 24.3050(6) 26.981538(2) 28.0855(3) 30.973761(2) 32.065(5) 35.453(2) 39.948(1) potassium calcium scandium titanium vanadium chromium manganese iron cobalt nickel copper zinc gallium germanium arsenic selenium bromine krypton 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 2+ 31 3+ 32 33 34 35 36 4 K Ca 3 Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr 4 39.0983(1) 40.078(4) 44.955910(8) 47.867(1) 50.9415(1) 51.9961(6) 54.938049(9) 55.845(2) 58.933200(9) 58.6934(2) 63.546(3) 65.409(4) 69.723(1) 72.64(1) 74.92160(2) 78.96(3) -

Discovery of Isotopes of Elements with Z ≥ 100

Discovery of Isotopes of Elements with Z ≥ 100 M. Thoennessen∗ National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory and Department of Physics and Astronomy, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA Abstract Currently, 159 isotopes of elements with Z ≥ 100 have been observed and the discovery of these isotopes is discussed here. For each isotope a brief synopsis of the first refereed publication, including the production and identification method, is presented. ∗Corresponding author. Email address: [email protected] (M. Thoennessen) Preprint submitted to Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables September 19, 2011 Contents 1. Introduction . 2 2. Discovery of 241−259Fm................................................................................. 3 3. Discovery of 245−260Md................................................................................. 8 4. Discovery of 250−260No.................................................................................. 11 5. Discovery of 252−260Lr.................................................................................. 14 6. Discovery of 253−267Rf.................................................................................. 16 7. Discovery of 256−270Db ................................................................................. 18 8. Discovery of 258−271Sg.................................................................................. 21 9. Discovery of 261−274Bh ................................................................................. 24 10. Discovery of 263−277Hs.................................................................................