Discovery of Isotopes of Elements with Z ≥ 100

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Understanding of the D-Block Elements in the Periodic Table Cite This: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C

Dalton Transactions View Article Online PERSPECTIVE View Journal | View Issue Evolution and understanding of the d-block elements in the periodic table Cite this: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C. Constable Received 20th February 2019, The d-block elements have played an essential role in the development of our present understanding of Accepted 6th March 2019 chemistry and in the evolution of the periodic table. On the occasion of the sesquicentenniel of the dis- DOI: 10.1039/c9dt00765b covery of the periodic table by Mendeleev, it is appropriate to look at how these metals have influenced rsc.li/dalton our understanding of periodicity and the relationships between elements. Introduction and periodic tables concerning objects as diverse as fruit, veg- etables, beer, cartoon characters, and superheroes abound in In the year 2019 we celebrate the sesquicentennial of the publi- our connected world.7 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. cation of the first modern form of the periodic table by In the commonly encountered medium or long forms of Mendeleev (alternatively transliterated as Mendelejew, the periodic table, the central portion is occupied by the Mendelejeff, Mendeléeff, and Mendeléyev from the Cyrillic d-block elements, commonly known as the transition elements ).1 The periodic table lies at the core of our under- or transition metals. These elements have played a critical rôle standing of the properties of, and the relationships between, in our understanding of modern chemistry and have proved to the 118 elements currently known (Fig. 1).2 A chemist can look be the touchstones for many theories of valence and bonding. -

NOBELIUM Element Symbol: No Atomic Number: 102

NOBELIUM Element Symbol: No Atomic Number: 102 An initiative of IYC 2011 brought to you by the RACI KERRY LAMB www.raci.org.au NOBELIUM Element symbol: No Atomic number: 102 The credit for discovering Nobelium was disputed with 3 different research teams claiming the discovery. While the first claim dates back to 1957, it was not until 1992 that the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry credited the discovery to a research team from Dubna in Russia for work they did in 1966. The element was named Nobelium in 1957 by the first of its claimed discoverers (the Nobel Institute in Sweden). It was named after Alfred Nobel, a Swedish chemist who invented dynamite, held more than 350 patents and bequeathed his fortune to the establishment of the Nobel Prizes. Nobelium is a synthetic element and does not occur in nature and has no known uses other than in scientific research as only tiny amounts of the element have ever been produced. Nobelium is radioactive and most likely metallic. The appearance and properties of Nobelium are unknown as insufficient amounts of the element have been produced. Nobelium is made by the bombardment of curium (Cm) with carbon nuclei. Its most stable isotope, 259No, has a half-life of 58 minutes and decays to Fermium (255Fm) through alpha decay or to Mendelevium (259Md) through electron capture. Provided by the element sponsor Freehills Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys ARTISTS DESCRIPTION I wanted to depict Alfred Nobel, the namesake of Nobelium, as a resolute young man, wearing the Laurel wreath which is the symbol of victory. -

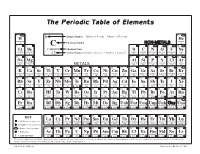

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons H 6 He HYDROGEN HELIUM 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM Atomic Weight = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Na Mg Al Si P S Cl Ar SODIUM MAGNESIUM ALUMINUM SILICON PHOSPHORUS SULFUR CHLORINE ARGON 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr POTASSIUM CALCIUM SCANDIUM TITANIUM VANADIUM CHROMIUM MANGANESE IRON COBALT NICKEL COPPER ZINC GALLIUM GERMANIUM ARSENIC SELENIUM BROMINE KRYPTON 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 Rb Sr Y Zr Nb Mo Tc Ru Rh Pd Ag Cd In Sn Sb Te I Xe RUBIDIUM STRONTIUM YTTRIUM ZIRCONIUM NIOBIUM MOLYBDENUM TECHNETIUM RUTHENIUM RHODIUM PALLADIUM SILVER CADMIUM INDIUM TIN ANTIMONY TELLURIUM IODINE XENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 Cs Ba Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt Au Hg Tl Pb Bi Po At Rn CESIUM BARIUM HAFNIUM TANTALUM TUNGSTEN RHENIUM OSMIUM IRIDIUM PLATINUM GOLD MERCURY THALLIUM LEAD BISMUTH POLONIUM ASTATINE RADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 Fr Ra Rf Db Sg Bh Hs Mt Ds Rg Uub Uut Uuq Uup Uuh Uus Uuo FRANCIUM RADIUM -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

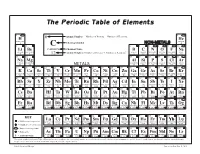

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium

SYNOPSIS An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium The discovery that copernicium can decay into a new isotope of darmstadtium and the observation of a previously unseen excited state of copernicium provide clues to the location of the “island of stability.” By Katherine Wright holy grail of nuclear physics is to understand the stability uncover its position. of the periodic table’s heaviest elements. The problem Ais, these elements only exist in the lab and are hard to The team made their discoveries while studying the decay of make. In an experiment at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy isotopes of flerovium, which they created by hitting a plutonium Ion Research in Germany, researchers have now observed a target with calcium ions. In their experiments, flerovium-288 previously unseen isotope of the heavy element darmstadtium (Z = 114, N = 174) decayed first into copernicium-284 and measured the decay of an excited state of an isotope of (Z = 112, N = 172) and then into darmstadtium-280 (Z = 110, another heavy element, copernicium [1]. The results could N = 170), a previously unseen isotope. They also measured an provide “anchor points” for theories that predict the stability of excited state of copernicium-282, another isotope of these heavy elements, says Anton Såmark-Roth, of Lund copernicium. Copernicium-282 is interesting because it University in Sweden, who helped conduct the experiments. contains an even number of protons and neutrons, and researchers had not previously measured an excited state of a A nuclide’s stability depends on how many protons (Z) and superheavy even-even nucleus, Såmark-Roth says. -

Darmstadtium, Roentgenium and Copernicium Form Strong Bonds with Cyanide

Darmstadtium, Roentgenium and Copernicium Form Strong Bonds With Cyanide Taye B. Demissie∗and Kenneth Ruudy March 23, 2017 Abstract We report the structures and properties of the cyanide complexes of three super- heavy elements (darmstadtium, roentgenium and copernicium) studied using two- and four-component relativistic methodologies. The electronic and structural properties of these complexes are compared to the corresponding complexes of platinum, gold and mercury. The results indicate that these superheavy elements form strong bonds with cyanide. Moreover, the calculated absorption spectra of these superheavy-element cyanides show similar trends to those of the corresponding heavy-atom cyanides. The calculated vibrational frequencies of the heavy-metal cyanides are in good agreement with available experimental results lending support to the quality of our calculated vibrational frequencies for the superheavy-atom cyanides. ∗Centre for Theoretical and Computational Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, UiT The Arctic Uni- versity of Norway, N-9037 Tromsø, Norway yCentre for Theoretical and Computational Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, UiT The Arctic Uni- versity of Norway, N-9037 Tromsø, Norway 1 Relativistic two- and four-component density-functional theory is used to demonstrate that the superheavy elements darmstadtium, roentgenium and copernicium form stable complexes with cyanide, providing new insight into the chemistry of these superheavy elements. 2 INTRODUCTION The term heavy atom refers roughly to elements in the 4th - -

Gas-Phase Chemistry of Element 114, Flerovium

EPJ Web of Conferences 131, 07003 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201613107003 Nobel Symposium NS160 – Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements Gas-phase chemistry of element 114, flerovium Alexander Yakushev1,2,a and Robert Eichler3,4 1 GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung GmbH, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany 2 Helmholtz-Institut Mainz, 55099 Mainz, Germany 3 Paul Scherrer Institut, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland 4 University of Bern, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, 3012 Bern, Switzerland Abstract. Element 114 was discovered in 2000 by the Dubna-Livermore collaboration, and in 2012 it was named flerovium. It belongs to the group 14 of the periodic table of elements. A strong relativistic stabilisation of 2 2 the valence shell 7s 7p1/2 is expected due to the orbital splitting and the 2 2 contraction not only of the 7s but also of the spherical 7p1/2 closed subshell, resulting in the enhanced volatility and inertness. Flerovium was studied chemically by gas-solid chromatography upon its adsorption on a gold surface. Two experimental results on Fl chemistry have been published so far. Based on observation of three atoms, a weak interaction of flerovium with gold was suggested in the first study. Authors of the second study concluded on the metallic character after the observation of two Fl atoms deposited on gold at room temperature. 1. Introduction Man-made superheavy elements (SHE, atomic number Z ≥ 104) are unique in two aspects. Their nuclei exist only due to nuclear shell effects, and their electron structure is influenced by increasingly important relativistic effects [1–3]. Recently the synthesis of elements 113, 115, 117 and 118 has been approved, thus, the discovery of all elements of the 7th row in the periodic table of elements with proton number Z up to 118 has been acknowledged [4]. -

Quest for Superheavy Nuclei Began in the 1940S with the Syn Time It Takes for Half of the Sample to Decay

FEATURES Quest for superheavy nuclei 2 P.H. Heenen l and W Nazarewicz -4 IService de Physique Nucleaire Theorique, U.L.B.-C.P.229, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Department ofPhysics, University ofTennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996 3Physics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 4Institute ofTheoretical Physics, University ofWarsaw, ul. Ho\.za 69, PL-OO-681 Warsaw, Poland he discovery of new superheavy nuclei has brought much The superheavy elements mark the limit of nuclear mass and T excitement to the atomic and nuclear physics communities. charge; they inhabit the upper right corner of the nuclear land Hopes of finding regions of long-lived superheavy nuclei, pre scape, but the borderlines of their territory are unknown. The dicted in the early 1960s, have reemerged. Why is this search so stability ofthe superheavy elements has been a longstanding fun important and what newknowledge can it bring? damental question in nuclear science. How can they survive the Not every combination ofneutrons and protons makes a sta huge electrostatic repulsion? What are their properties? How ble nucleus. Our Earth is home to 81 stable elements, including large is the region of superheavy elements? We do not know yet slightly fewer than 300 stable nuclei. Other nuclei found in all the answers to these questions. This short article presents the nature, although bound to the emission ofprotons and neutrons, current status ofresearch in this field. are radioactive. That is, they eventually capture or emit electrons and positrons, alpha particles, or undergo spontaneous fission. Historical Background Each unstable isotope is characterized by its half-life (T1/2) - the The quest for superheavy nuclei began in the 1940s with the syn time it takes for half of the sample to decay. -

Three Related Topics on the Periodic Tables of Elements

Three related topics on the periodic tables of elements Yoshiteru Maeno*, Kouichi Hagino, and Takehiko Ishiguro Department of physics, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan * [email protected] (The Foundations of Chemistry: received 30 May 2020; accepted 31 July 2020) Abstaract: A large variety of periodic tables of the chemical elements have been proposed. It was Mendeleev who proposed a periodic table based on the extensive periodic law and predicted a number of unknown elements at that time. The periodic table currently used worldwide is of a long form pioneered by Werner in 1905. As the first topic, we describe the work of Pfeiffer (1920), who refined Werner’s work and rearranged the rare-earth elements in a separate table below the main table for convenience. Today’s widely used periodic table essentially inherits Pfeiffer’s arrangements. Although long-form tables more precisely represent electron orbitals around a nucleus, they lose some of the features of Mendeleev’s short-form table to express similarities of chemical properties of elements when forming compounds. As the second topic, we compare various three-dimensional helical periodic tables that resolve some of the shortcomings of the long-form periodic tables in this respect. In particular, we explain how the 3D periodic table “Elementouch” (Maeno 2001), which combines the s- and p-blocks into one tube, can recover features of Mendeleev’s periodic law. Finally we introduce a topic on the recently proposed nuclear periodic table based on the proton magic numbers (Hagino and Maeno 2020). Here, the nuclear shell structure leads to a new arrangement of the elements with the proton magic-number nuclei treated like noble-gas atoms. -

Chemical Element 112 Named 'Copernicium' 24 February 2010

Chemical element 112 named 'Copernicium' 24 February 2010 IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Copernicium is the sixth chemical element GSI Chemistry) accepted the name proposed by the scientist named. The other elements carry the international discovering team around Sigurd names Bohrium (element 107), Hassium (element Hofmann at the GSI Helmholtzzentrum. The team 108), Meitnerium (element 109), Darmstadtium had suggested "Cp" as the chemical symbol for the (element 110), and Roentgenium (element 111). 21 new element. However, since the chemical symbol scientists from Germany, Finland, Russia, and "Cp" gave cause for concerns, as this abbreviation Slovakia collaborated in the GSI experiments that also has other scientific meanings, the discoverers lead to the discovery of element 112. and IUPAC agreed to change the symbol to "Cn". Copernicium is 277 times heavier than hydrogen, More information: 'Copernicium' proposed as making it the heaviest element officially recognized name for newly discovered element 112 -- by IUPAC. www.physorg.com/news166791177.html The suggested name "Copernicium" in honor of Nicolaus Copernicus follows the tradition of naming chemical elements after merited scientists. IUPAC Provided by Helmholtz Association of German officially announced the endorsement of the new Research Centres element's name on February 19th, Nicolaus Copernicus' birthday. Copernicus was born on February 19, 1473 in Toru?, Poland. His work in the field of astronomy is the basis for our modern, heliocentric world view, which states that the Sun is the center of our solar system with the Earth and all the other planets circling around it. An international team of scientists headed by Sigurd Hofmann was able to produce the element copernicium at GSI for the first time already on February 9, 1996. -

Interactive Chemistry Exhibition

United Nations International Year All-Russian United Nations International Year All-Russian Educational, Scientific and of the Periodic Table Science Educational, Scientific and of the Periodic Table Science Cultural Organization of Chemical Elements Festival Cultural Organization of Chemical Elements Festival Science for All: Interactive Chemistry Exhibition The Management Committee of the International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements (IYPT2019) in partnership with All - Russian Science Festival invites you to visit an Interactive Exhibition on Chemistry at UNESCO Headquarters from 28 to 30 January 2019. Launched as part of the Opening Ceremony of the International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements (IYPT2019) on January 29th, this exhibition will travel around the world during the year 2019. Science for All: Interactive Chemistry Exhibition - an exciting journey into the world of «living» Chemistry where you will have the opportunity to feel like a real scientist, to carry out a series of chemical experiments, discover the history, immerse yourself into virtual reality and explore outer space. 1. Historical zone. Take a selfie in Mendeleev’s Cabinet This year, it is a century and a half since the creation of the Periodic Table. In 1869 there were no Internet, computers, smartphones and many other modern devices. We reconstructed the study of a chemist who worked in the nineteenth century. In the exhibition, visitors can see the basic scientific tools of that time, look at the first publication of the Table, and even take a selfie with its creator, Dmitrii Ivanovich Mendeleev. 2. Zone of space. Find out where it all came from How did hydrogen appear? And Iron? And what about Gold? Answers to these seemingly simple questions lie in the depths of the Universe.