Darmstadtium, Roentgenium and Copernicium Form Strong Bonds with Cyanide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Understanding of the D-Block Elements in the Periodic Table Cite This: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C

Dalton Transactions View Article Online PERSPECTIVE View Journal | View Issue Evolution and understanding of the d-block elements in the periodic table Cite this: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C. Constable Received 20th February 2019, The d-block elements have played an essential role in the development of our present understanding of Accepted 6th March 2019 chemistry and in the evolution of the periodic table. On the occasion of the sesquicentenniel of the dis- DOI: 10.1039/c9dt00765b covery of the periodic table by Mendeleev, it is appropriate to look at how these metals have influenced rsc.li/dalton our understanding of periodicity and the relationships between elements. Introduction and periodic tables concerning objects as diverse as fruit, veg- etables, beer, cartoon characters, and superheroes abound in In the year 2019 we celebrate the sesquicentennial of the publi- our connected world.7 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. cation of the first modern form of the periodic table by In the commonly encountered medium or long forms of Mendeleev (alternatively transliterated as Mendelejew, the periodic table, the central portion is occupied by the Mendelejeff, Mendeléeff, and Mendeléyev from the Cyrillic d-block elements, commonly known as the transition elements ).1 The periodic table lies at the core of our under- or transition metals. These elements have played a critical rôle standing of the properties of, and the relationships between, in our understanding of modern chemistry and have proved to the 118 elements currently known (Fig. 1).2 A chemist can look be the touchstones for many theories of valence and bonding. -

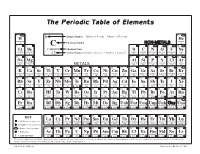

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons H 6 He HYDROGEN HELIUM 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM Atomic Weight = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Na Mg Al Si P S Cl Ar SODIUM MAGNESIUM ALUMINUM SILICON PHOSPHORUS SULFUR CHLORINE ARGON 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 K Ca Sc Ti V Cr Mn Fe Co Ni Cu Zn Ga Ge As Se Br Kr POTASSIUM CALCIUM SCANDIUM TITANIUM VANADIUM CHROMIUM MANGANESE IRON COBALT NICKEL COPPER ZINC GALLIUM GERMANIUM ARSENIC SELENIUM BROMINE KRYPTON 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 Rb Sr Y Zr Nb Mo Tc Ru Rh Pd Ag Cd In Sn Sb Te I Xe RUBIDIUM STRONTIUM YTTRIUM ZIRCONIUM NIOBIUM MOLYBDENUM TECHNETIUM RUTHENIUM RHODIUM PALLADIUM SILVER CADMIUM INDIUM TIN ANTIMONY TELLURIUM IODINE XENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 Cs Ba Hf Ta W Re Os Ir Pt Au Hg Tl Pb Bi Po At Rn CESIUM BARIUM HAFNIUM TANTALUM TUNGSTEN RHENIUM OSMIUM IRIDIUM PLATINUM GOLD MERCURY THALLIUM LEAD BISMUTH POLONIUM ASTATINE RADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 Fr Ra Rf Db Sg Bh Hs Mt Ds Rg Uub Uut Uuq Uup Uuh Uus Uuo FRANCIUM RADIUM -

An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium

SYNOPSIS An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium The discovery that copernicium can decay into a new isotope of darmstadtium and the observation of a previously unseen excited state of copernicium provide clues to the location of the “island of stability.” By Katherine Wright holy grail of nuclear physics is to understand the stability uncover its position. of the periodic table’s heaviest elements. The problem Ais, these elements only exist in the lab and are hard to The team made their discoveries while studying the decay of make. In an experiment at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy isotopes of flerovium, which they created by hitting a plutonium Ion Research in Germany, researchers have now observed a target with calcium ions. In their experiments, flerovium-288 previously unseen isotope of the heavy element darmstadtium (Z = 114, N = 174) decayed first into copernicium-284 and measured the decay of an excited state of an isotope of (Z = 112, N = 172) and then into darmstadtium-280 (Z = 110, another heavy element, copernicium [1]. The results could N = 170), a previously unseen isotope. They also measured an provide “anchor points” for theories that predict the stability of excited state of copernicium-282, another isotope of these heavy elements, says Anton Såmark-Roth, of Lund copernicium. Copernicium-282 is interesting because it University in Sweden, who helped conduct the experiments. contains an even number of protons and neutrons, and researchers had not previously measured an excited state of a A nuclide’s stability depends on how many protons (Z) and superheavy even-even nucleus, Såmark-Roth says. -

ROENTGENIUM Element Symbol: Rg Atomic Number: 111

ROENTGENIUM Element Symbol: Rg Atomic Number: 111 An initiative of IYC 2011 brought to you by the RACI PATRICIA ZUBER www.raci.org.au ROENTGENIUM Element symbol: Rg Atomic number: 111 Roentgenium has the symbol Rg and atomic number 111. However, it is not a stable element and can only be produced by cold fusion between other elements (for example by bombarding bismuth with nickel). Once formed, it is a synthetic radioactive element that falls apart in less than 20 sec. Therefore, there is currently no direct use for it. This element was first discovered by the Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung (GSI) in Darmstadt, Germany in 1994. GSI also proposed a name for this new element: Roentgenium. They honoured the achievements of Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, a physicist, who discovered X-rays in 1895 while being professor at the University of Wuerzburg in Germany. Röntgen is considered the father of diagnostic radiology, the medical specialty which uses imaging to diagnose disease. Roentgen never patented anything because he believed that knowledge should be available for everybody. He received the very first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901. Provided by the element sponsor Martina Stenzel ARTISTS DESCRIPTION Lino cut, silk screen Roentgenium is a synthetic radioactive element produced by cold fusion. It has a half life of 20 seconds and decays by spontaneous fission. Not an easy element to create an image from! I decided to use a diagram of its atomic structure and fission lines as a basis for a relief image. I cut a paper stencil of Rg 111 and silk screened it in silver across the centre of this printed image. -

Physics of Superheavy Elements Kouichi Hagino

Frontiers in Science II 2013.11.6 Physics of superheavy elements Kouichi Hagino Nuclear Theory Group, Department of Physics, Tohoku University What is nuclear physics? What are superheavy elements? How to create superheavy elements? What are chemical properties of superheavy elements? Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei What would you see if you magnified the dog? ~ 50 cm Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei cells ~ 50 cm ~ m = 10-6 m Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei DNA cells -8 ~ 50 cm ~ m = 10-6 m ~ 10 m atom All things are made of atoms. ~ 10-10 m All things are made of atoms. • Thales, Democritus (ancient Greek) • Dalton (chemist, 19th century) • Boltzmann(19th century) • Einstein (1905) ~ 10-10 m STM image (surface physics group, Tohoku university) Introduction: atoms and atomic nuclei DNA cells -8 ~ 50 cm ~ 10 m atom atomic nucleus ~ 10-15 m ~ 10-10 m proton (+e) neutron (no charge) electron cloud (-e) Neutral atoms: # of protons = # of electrons Chemical properties of atoms # of electrons Mp ~ Mn ~ 2000 Me the mass of atom ~ the mass of nucleus Periodic table of chemical elements tabular arrangement of chemical elements based on the atomic numbers (= # of electrons = # of protons) What are we made of ? oxygen 43 kg cerium 40 mg gallium 0.7 mg carbon 16 kg barium 22 mg tellurium 0.7 mg hydrogen 7 kg iodine 20 mg yttrium 0.6 mg nitrogen 1.8 kg tin 20 mg bismuth 0.5 mg calcium 1.0 kg titanium 20 mg thallium 0.5 mg phosphorus 780 g boron 18 mg indium 0.4 mg potassium 140 g nickel 15 mg gold 0.2 mg sulphur 140 g selenium -

Roentgenium Periodic Table of Elements

Periodic Table of Elements https://periodic-table.pro/Element/Rg/enView online at https://periodic-table.pro Roentgenium Roentgenium is named for Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen, who discovered x-rays. His element is highly radioactive, but disappointingly it does not, despite its name, emit x-rays when it decays. 01. OVERVIEW Symbol Rg Atomic number 111 Atomic weight 272 Density N/A Melting point N/A Boiling point N/A 02. THERMAL PROPERTIES Phase N/A Melting point N/A Boiling point N/A Absolute melting point N/A Absolute boiling point N/A Critical pressure N/A Critical temperature N/A Heat of fusion N/A Heat of vaporization N/A Heat of combustion N/A Specific heat N/A Adiabatic index N/A Neel point N/A Thermal conductivity N/A Thermal expansion N/A 03. PHYSICAL PROPERTIES Density N/A Density (liquid) N/A Molar volume N/A Molar mass 282.169u Brinell hardness N/A Mohs hardness N/A Vickers hardness N/A Bulk modulus N/A Shear modulus N/A Young modulus N/A Poisson ratio N/A Refractive index N/A Speed of sound N/A Thermal conductivity N/A Thermal expansion N/A 04. REACTIVITY Valence N/A Electronegativity N/A Electron affinity N/A Ionization energies N/A 05. SAFETY Autoignition point N/A Flashpoint N/A Heat of combustion N/A 06. CLASSIFICATIONS Alternate names N/A Names of allotropes N/A Block, Group, Period d, 11, 7 Electron configuration [Rn]5f¹⁴6d⁹7s² Color N/A Discovery 1994 in Germany Gas phase N/A 07. -

Periodic Table 1 Periodic Table

Periodic table 1 Periodic table This article is about the table used in chemistry. For other uses, see Periodic table (disambiguation). The periodic table is a tabular arrangement of the chemical elements, organized on the basis of their atomic numbers (numbers of protons in the nucleus), electron configurations , and recurring chemical properties. Elements are presented in order of increasing atomic number, which is typically listed with the chemical symbol in each box. The standard form of the table consists of a grid of elements laid out in 18 columns and 7 Standard 18-column form of the periodic table. For the color legend, see section Layout, rows, with a double row of elements under the larger table. below that. The table can also be deconstructed into four rectangular blocks: the s-block to the left, the p-block to the right, the d-block in the middle, and the f-block below that. The rows of the table are called periods; the columns are called groups, with some of these having names such as halogens or noble gases. Since, by definition, a periodic table incorporates recurring trends, any such table can be used to derive relationships between the properties of the elements and predict the properties of new, yet to be discovered or synthesized, elements. As a result, a periodic table—whether in the standard form or some other variant—provides a useful framework for analyzing chemical behavior, and such tables are widely used in chemistry and other sciences. Although precursors exist, Dmitri Mendeleev is generally credited with the publication, in 1869, of the first widely recognized periodic table. -

Critical Mineral Resources of the United States— Economic and Environmental Geology and Prospects for Future Supply

Critical Mineral Resources of the United States— Economic and Environmental Geology and Prospects for Future Supply Professional Paper 1802 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Periodic Table of Elements 1A 8A 1 2 hydrogen helium 1.008 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 7A 4.003 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 lithium beryllium boron carbon nitrogen oxygen fluorine neon 6.94 9.012 10.81 12.01 14.01 16.00 19.00 20.18 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 sodium magnesium aluminum silicon phosphorus sulfur chlorine argon 22.99 24.31 3B 4B 5B 6B 7B 8B 11B 12B 26.98 28.09 30.97 32.06 35.45 39.95 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 potassium calcium scandium titanium vanadium chromium manganese iron cobalt nickel copper zinc gallium germanium arsenic selenium bromine krypton 39.10 40.08 44.96 47.88 50.94 52.00 54.94 55.85 58.93 58.69 63.55 65.39 69.72 72.64 74.92 78.96 79.90 83.79 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 rubidium strontium yttrium zirconium niobium molybdenum technetium ruthenium rhodium palladium silver cadmium indium tin antimony tellurium iodine xenon 85.47 87.62 88.91 91.22 92.91 95.96 (98) 101.1 102.9 106.4 107.9 112.4 114.8 118.7 121.8 127.6 126.9 131.3 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 cesium barium hafnium tantalum tungsten rhenium osmium iridium platinum gold mercury thallium lead bismuth polonium astatine radon 132.9 137.3 178.5 180.9 183.9 186.2 190.2 192.2 195.1 197.0 200.5 204.4 207.2 209.0 (209) (210)(222) 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 francium radium rutherfordium -

Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2015 Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants John Dustin Despotopulos University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Chemistry Commons Repository Citation Despotopulos, John Dustin, "Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants" (2015). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2345. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7645877 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVESTIGATION OF FLEROVIUM AND ELEMENT 115 HOMOLOGS WITH MACROCYCLIC EXTRACTANTS By John Dustin Despotopulos Bachelor of Science in Chemistry University of Oregon 2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy -

BNL-79513-2007-CP Standard Atomic Weights Tables 2007 Abridged To

BNL-79513-2007-CP Standard Atomic Weights Tables 2007 Abridged to Four and Five Significant Figures Norman E. Holden Energy Sciences & Technology Department National Nuclear Data Center Brookhaven National Laboratory P.O. Box 5000 Upton, NY 11973-5000 www.bnl.gov Prepared for the 44th IUPAC General Assembly, in Torino, Italy August 2007 Notice: This manuscript has been authored by employees of Brookhaven Science Associates, LLC under Contract No. DE-AC02-98CH10886 with the U.S. Department of Energy. The publisher by accepting the manuscript for publication acknowledges that the United States Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, world-wide license to publish or reproduce the published form of this manuscript, or allow others to do so, for United States Government purposes. This preprint is intended for publication in a journal or proceedings. Since changes may be made before publication, it may not be cited or reproduced without the author’s permission. DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, nor any of their contractors, subcontractors, or their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or any third party’s use or the results of such use of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof or its contractors or subcontractors. -

Python Module Index 79

mendeleev Documentation Release 0.9.0 Lukasz Mentel Sep 04, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Getting started 3 1.1 Overview.................................................3 1.2 Contributing...............................................3 1.3 Citing...................................................3 1.4 Related projects.............................................4 1.5 Funding..................................................4 2 Installation 5 3 Tutorials 7 3.1 Quick start................................................7 3.2 Bulk data access............................................. 14 3.3 Electronic configuration......................................... 21 3.4 Ions.................................................... 23 3.5 Visualizing custom periodic tables.................................... 25 3.6 Advanced visulization tutorial...................................... 27 3.7 Jupyter notebooks............................................ 30 4 Data 31 4.1 Elements................................................. 31 4.2 Isotopes.................................................. 35 5 Electronegativities 37 5.1 Allen................................................... 37 5.2 Allred and Rochow............................................ 38 5.3 Cottrell and Sutton............................................ 38 5.4 Ghosh................................................... 38 5.5 Gordy................................................... 39 5.6 Li and Xue................................................ 39 5.7 Martynov and Batsanov........................................ -

Synthesis of Superheavy Elements by Cold Fusion

Radiochim. Acta 99, 405–428 (2011) / DOI 10.1524/ract.2011.1854 © by Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, München Synthesis of superheavy elements by cold fusion By S. Hofmann1,2,∗ 1 GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung, Planckstraße 1, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany 2 Institut für Kernphysik, Goethe-Universität, Max von Laue-Straße 1, 60438 Frankfurt, Germany (Received February 3, 2011; accepted in revised form April 18, 2011) Superheavy elements / Synthesis / Cold fusion / in 1972, and the RILAC (variable-frequency linear acceler- Cross-sections / Decay properties / Recoil separators / ator) at the RIKEN Nishina Center in Saitama near Tokio in Detector systems 1980. In the middle of the 1960s the concept of the macrosco- pic-microscopic model for calculating binding energies Summary. The new elements from Z = 107 to 112 were of nuclei also at large deformations was invented by synthesized in cold fusion reactions based on targets of lead V. M. Strutinsky [3]. Using this method, a number of the and bismuth. The principle physical concepts are presented measured phenomena could be naturally explained by con- which led to the application of this reaction type in search sidering the change of binding energy as function of defor- experiments for new elements. Described are the technical mation. In particular, it became possible now to calculate the developments from early mechanical devices to experiments with recoil separators. An overview is given of present ex- binding energy of a heavy fissioning nucleus at each point of periments which use cold fusion for systematic studies and the fission path and thus to determine the fission barrier. synthesis of new isotopes.