Atomic Weights of the Elements 2011 (IUPAC Technical Report)*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Important Role of Dysprosium in Modern Permanent Magnets

The Important Role of Dysprosium in Modern Permanent Magnets Introduction Dysprosium is one of a group of elements called the Rare Earths. Rare earth elements consist of the Lanthanide series of 15 elements plus yttrium and scandium. Yttrium and scandium are included because of similar chemical behavior. The rare earths are divided into light and heavy based on atomic weight and the unique chemical and magnetic properties of each of these categories. Dysprosium (Figure 1) is considered a heavy rare earth element (HREE). One of the more important uses for dysprosium is in neodymium‐iron‐ boron (Neo) permanent magnets to improve the magnets’ resistance to demagnetization, and by extension, its high temperature performance. Neo magnets have become essential for a wide range of consumer, transportation, power generation, defense, aerospace, medical, industrial and other products. Along with terbium (Tb), Dysprosium (Dy) Figure 1: Dysprosium Metal(1) is also used in magnetostrictive devices, but by far the greater usage is in permanent magnets. The demand for Dy has been outstripping its supply. An effect of this continuing shortage is likely to be a slowing of the commercial rollout or a redesigning of a number of Clean Energy applications, including electric traction drives for vehicles and permanent magnet generators for wind turbines. The shortage and associated high prices are also upsetting the market for commercial and industrial motors and products made using them. Background Among the many figures of merit for permanent magnets two are of great importance regarding use of Dy. One key characteristic of a permanent magnet is its resistance to demagnetization, which is quantified by the value of Intrinsic Coercivity (HcJ or Hci). -

Treatment Outcome Following Use of the Erbium, Chromium:Yttrium

Treatment outcome following use IN BRIEF • Highlights that successful treatment RESEARCH of peri-implantitis is unpredictable and of the erbium, chromium:yttrium, usually involves the need for surgery. • Outlines a minimalistic treatment approach for peri-implantitis with promising results after six months. scandium, gallium, garnet laser • Suggests that the protocol described may be of use in a pilot study or controlled in the non-surgical management clinical trial. of peri-implantitis: a case series R. Al-Falaki,*1 M. Cronshaw2 and F. J. Hughes3 VERIFIABLE CPD PAPER Aim To date there is no consensus on the appropriate usage of lasers in the management of peri-implantitis. Our aim was to conduct a retrospective clinical analysis of a case series of implants treated using an erbium, chromium:yttrium, scandium, gallium, garnet laser. Materials and methods Twenty-eight implants with peri-implantitis in 11 patients were treated with an Er,Cr:YSGG laser (68 sites >4 mm), using a 14 mm, 500 μm diameter, 60º (85%) radial firing tip (1.5 W, 30 Hz, short (140 μs) pulse, 50 mJ/pulse, 50% water, 40% air). Probing depths were recorded at baseline after 2 months and 6 months, along with the presence of bleeding on probing. Results The age range was 27-69 years (mean 55.9); mean pocket depth at baseline was 6.64 ± SD 1.48 mm (range 5-12 mm),with a mean residual depth of 3.29 ± 1.02 mm (range 1-6 mm) after 2 months, and 2.97 ± 0.7 mm (range 1-9 mm) at 6 months. -

Evolution and Understanding of the D-Block Elements in the Periodic Table Cite This: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C

Dalton Transactions View Article Online PERSPECTIVE View Journal | View Issue Evolution and understanding of the d-block elements in the periodic table Cite this: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C. Constable Received 20th February 2019, The d-block elements have played an essential role in the development of our present understanding of Accepted 6th March 2019 chemistry and in the evolution of the periodic table. On the occasion of the sesquicentenniel of the dis- DOI: 10.1039/c9dt00765b covery of the periodic table by Mendeleev, it is appropriate to look at how these metals have influenced rsc.li/dalton our understanding of periodicity and the relationships between elements. Introduction and periodic tables concerning objects as diverse as fruit, veg- etables, beer, cartoon characters, and superheroes abound in In the year 2019 we celebrate the sesquicentennial of the publi- our connected world.7 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. cation of the first modern form of the periodic table by In the commonly encountered medium or long forms of Mendeleev (alternatively transliterated as Mendelejew, the periodic table, the central portion is occupied by the Mendelejeff, Mendeléeff, and Mendeléyev from the Cyrillic d-block elements, commonly known as the transition elements ).1 The periodic table lies at the core of our under- or transition metals. These elements have played a critical rôle standing of the properties of, and the relationships between, in our understanding of modern chemistry and have proved to the 118 elements currently known (Fig. 1).2 A chemist can look be the touchstones for many theories of valence and bonding. -

Table 2.Iii.1. Fissionable Isotopes1

FISSIONABLE ISOTOPES Charles P. Blair Last revised: 2012 “While several isotopes are theoretically fissionable, RANNSAD defines fissionable isotopes as either uranium-233 or 235; plutonium 238, 239, 240, 241, or 242, or Americium-241. See, Ackerman, Asal, Bale, Blair and Rethemeyer, Anatomizing Radiological and Nuclear Non-State Adversaries: Identifying the Adversary, p. 99-101, footnote #10, TABLE 2.III.1. FISSIONABLE ISOTOPES1 Isotope Availability Possible Fission Bare Critical Weapon-types mass2 Uranium-233 MEDIUM: DOE reportedly stores Gun-type or implosion-type 15 kg more than one metric ton of U- 233.3 Uranium-235 HIGH: As of 2007, 1700 metric Gun-type or implosion-type 50 kg tons of HEU existed globally, in both civilian and military stocks.4 Plutonium- HIGH: A separated global stock of Implosion 10 kg 238 plutonium, both civilian and military, of over 500 tons.5 Implosion 10 kg Plutonium- Produced in military and civilian 239 reactor fuels. Typically, reactor Plutonium- grade plutonium (RGP) consists Implosion 40 kg 240 of roughly 60 percent plutonium- Plutonium- 239, 25 percent plutonium-240, Implosion 10-13 kg nine percent plutonium-241, five 241 percent plutonium-242 and one Plutonium- percent plutonium-2386 (these Implosion 89 -100 kg 242 percentages are influenced by how long the fuel is irradiated in the reactor).7 1 This table is drawn, in part, from Charles P. Blair, “Jihadists and Nuclear Weapons,” in Gary A. Ackerman and Jeremy Tamsett, ed., Jihadists and Weapons of Mass Destruction: A Growing Threat (New York: Taylor and Francis, 2009), pp. 196-197. See also, David Albright N 2 “Bare critical mass” refers to the absence of an initiator or a reflector. -

Critical Mineral - Antimony

Critical Mineral - Antimony Listed as one of the 35 critical minerals by the U.S. Government, antimony strengthens metal in munitions, is used in batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines, and therefore plays an important role in our defense and energy industries. Today, China and Russia control the world’s supply of antimony, leaving the U.S. without a direct source of this mineral which is important to our national, economic, and environmental future. Perpetua Resources is developing the only commercially viable antimony mine in the U.S. to source supply for new battery and solar technologies, as well as alloys critical for national security products. CRITICAL TO THE GREEN ECONOMY Critical minerals are vital to national and economic security, as well as the future green economy. Domestic sourcing and production of all critical minerals has bi-partisan political support. Antimony is critical in the use of bearings for wind turbines, glass clarifcation for solar energy projects, and cable sheathing for wiring and as an important component in many electrical and solid state circuitry components. For defense, antimony use is critical in fame retardants, primers, and ammunition. Antimony has current and projected widespread use for the U.S. green energy sectors. Recent studies point to antimony playing a substantial role in the development of large-scale, safe, affordable battery storage technology. A limited supply of antimony and lack of advanced new antimony development projects are considered key risks to this technology moving forward. SUPPLY Currently, 92% antimony Based on the 2020 Feasibility Study the Stibnite Gold production is dominated by Project is expected to produce enough antimony to supply approximately 30% of U.S. -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

BISMUTH LEAD ALLOY Synonyms BISMUTH ALLOY, 5805, HS CODE 78019900 ● NYRSTAR LEAD ALLOYS

1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE MATERIAL AND SUPPLIER 1.1 Product identifier Product name BISMUTH LEAD ALLOY Synonyms BISMUTH ALLOY, 5805, HS CODE 78019900 ● NYRSTAR LEAD ALLOYS 1.2 Uses and uses advised against Uses ALLOY Used for further refining of bismuth and lead metals. 1.3 Details of the supplier of the product Supplier name NYRSTAR PORT PIRIE Address PO Box 219, Port Pirie, SA, 5540, AUSTRALIA Telephone (08) 8638 1500 Fax (08) 8638 1583 Website http://www.nyrstar.com 1.4 Emergency telephone numbers Emergency (08) 8638 1500 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION 2.1 Classification of the substance or mixture CLASSIFIED AS HAZARDOUS ACCORDING TO SAFE WORK AUSTRALIA CRITERIA GHS classifications Acute Toxicity: Oral: Category 4 Acute Toxicity: Inhalation: Category 4 Toxic to Reproduction: Category 1A Specific Target Organ Systemic Toxicity (Repeated Exposure): Category 2 2.2 GHS Label elements Signal word DANGER Pictograms Hazard statements H302 Harmful if swallowed. H332 Harmful if inhaled. H360 May damage fertility or the unborn child. H373 May cause damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure. Prevention statements P202 Do not handle until all safety precautions have been read and understood. P260 Do not breathe dust/fume/gas/mist/vapours/spray. P264 Wash thoroughly after handling. P270 Do not eat, drink or smoke when using this product. P271 Use only outdoors or in a well-ventilated area. P281 Use personal protective equipment as required. SDS Date: 08 Jun 2018 Page 1 of 7 Version No: 1.3 PRODUCT NAME BISMUTH LEAD ALLOY Response statements P304 + P340 IF INHALED: Remove to fresh air and keep at rest in a position comfortable for breathing. -

The Separation of Bismuth-213 from Actinium-225 and the Ion Exchange Properties of the Alkali Metal Cations with an Inorganic Resin

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2017 The Separation of Bismuth-213 from Actinium-225 and the Ion Exchange Properties of the Alkali Metal Cations with an Inorganic Resin Mark Alan Moore University of Tennessee Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Moore, Mark Alan, "The Separation of Bismuth-213 from Actinium-225 and the Ion Exchange Properties of the Alkali Metal Cations with an Inorganic Resin. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2017. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/4848 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Mark Alan Moore entitled "The Separation of Bismuth-213 from Actinium-225 and the Ion Exchange Properties of the Alkali Metal Cations with an Inorganic Resin." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Chemical Engineering. Robert Counce, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Paul Dalhaimer, Howard Hall, George Schweitzer, Jack Watson Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Separation of Bismuth-213 from Actinium-225 and the Ion Exchange Properties of the Alkali Metal Cations with an Inorganic Resin A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Mark Alan Moore December 2017 Copyright © 2017 by Mark A. -

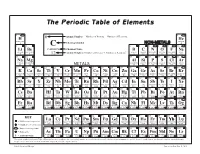

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium

SYNOPSIS An Octad for Darmstadtium and Excitement for Copernicium The discovery that copernicium can decay into a new isotope of darmstadtium and the observation of a previously unseen excited state of copernicium provide clues to the location of the “island of stability.” By Katherine Wright holy grail of nuclear physics is to understand the stability uncover its position. of the periodic table’s heaviest elements. The problem Ais, these elements only exist in the lab and are hard to The team made their discoveries while studying the decay of make. In an experiment at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy isotopes of flerovium, which they created by hitting a plutonium Ion Research in Germany, researchers have now observed a target with calcium ions. In their experiments, flerovium-288 previously unseen isotope of the heavy element darmstadtium (Z = 114, N = 174) decayed first into copernicium-284 and measured the decay of an excited state of an isotope of (Z = 112, N = 172) and then into darmstadtium-280 (Z = 110, another heavy element, copernicium [1]. The results could N = 170), a previously unseen isotope. They also measured an provide “anchor points” for theories that predict the stability of excited state of copernicium-282, another isotope of these heavy elements, says Anton Såmark-Roth, of Lund copernicium. Copernicium-282 is interesting because it University in Sweden, who helped conduct the experiments. contains an even number of protons and neutrons, and researchers had not previously measured an excited state of a A nuclide’s stability depends on how many protons (Z) and superheavy even-even nucleus, Såmark-Roth says. -

High-Temperature Structural Evolution of Caesium and Rubidium Triiodoplumbates D.M

High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium triiodoplumbates D.M. Trots, S.V. Myagkota To cite this version: D.M. Trots, S.V. Myagkota. High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium tri- iodoplumbates. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, Elsevier, 2009, 69 (10), pp.2520. 10.1016/j.jpcs.2008.05.007. hal-00565442 HAL Id: hal-00565442 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00565442 Submitted on 13 Feb 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Author’s Accepted Manuscript High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium triiodoplumbates D.M. Trots, S.V. Myagkota PII: S0022-3697(08)00173-X DOI: doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2008.05.007 Reference: PCS 5491 To appear in: Journal of Physics and www.elsevier.com/locate/jpcs Chemistry of Solids Received date: 31 January 2008 Revised date: 2 April 2008 Accepted date: 14 May 2008 Cite this article as: D.M. Trots and S.V. Myagkota, High-temperature structural evolution of caesium and rubidium triiodoplumbates, Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2008.05.007 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Of the Periodic Table

of the Periodic Table teacher notes Give your students a visual introduction to the families of the periodic table! This product includes eight mini- posters, one for each of the element families on the main group of the periodic table: Alkali Metals, Alkaline Earth Metals, Boron/Aluminum Group (Icosagens), Carbon Group (Crystallogens), Nitrogen Group (Pnictogens), Oxygen Group (Chalcogens), Halogens, and Noble Gases. The mini-posters give overview information about the family as well as a visual of where on the periodic table the family is located and a diagram of an atom of that family highlighting the number of valence electrons. Also included is the student packet, which is broken into the eight families and asks for specific information that students will find on the mini-posters. The students are also directed to color each family with a specific color on the blank graphic organizer at the end of their packet and they go to the fantastic interactive table at www.periodictable.com to learn even more about the elements in each family. Furthermore, there is a section for students to conduct their own research on the element of hydrogen, which does not belong to a family. When I use this activity, I print two of each mini-poster in color (pages 8 through 15 of this file), laminate them, and lay them on a big table. I have students work in partners to read about each family, one at a time, and complete that section of the student packet (pages 16 through 21 of this file). When they finish, they bring the mini-poster back to the table for another group to use.