History of the Seaborg Institute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Understanding of the D-Block Elements in the Periodic Table Cite This: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C

Dalton Transactions View Article Online PERSPECTIVE View Journal | View Issue Evolution and understanding of the d-block elements in the periodic table Cite this: Dalton Trans., 2019, 48, 9408 Edwin C. Constable Received 20th February 2019, The d-block elements have played an essential role in the development of our present understanding of Accepted 6th March 2019 chemistry and in the evolution of the periodic table. On the occasion of the sesquicentenniel of the dis- DOI: 10.1039/c9dt00765b covery of the periodic table by Mendeleev, it is appropriate to look at how these metals have influenced rsc.li/dalton our understanding of periodicity and the relationships between elements. Introduction and periodic tables concerning objects as diverse as fruit, veg- etables, beer, cartoon characters, and superheroes abound in In the year 2019 we celebrate the sesquicentennial of the publi- our connected world.7 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported Licence. cation of the first modern form of the periodic table by In the commonly encountered medium or long forms of Mendeleev (alternatively transliterated as Mendelejew, the periodic table, the central portion is occupied by the Mendelejeff, Mendeléeff, and Mendeléyev from the Cyrillic d-block elements, commonly known as the transition elements ).1 The periodic table lies at the core of our under- or transition metals. These elements have played a critical rôle standing of the properties of, and the relationships between, in our understanding of modern chemistry and have proved to the 118 elements currently known (Fig. 1).2 A chemist can look be the touchstones for many theories of valence and bonding. -

Early Synchrotrons in Britain, and Early Work for Cern

EARLY SYNCHROTRONS IN BRITAIN, AND EARLY WORK FOR CERN J. D. Lawson Formerly Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Chilton, Oxon, UK Abstract Early work on electron synchrotrons in the UK, including an account of the conversion of a small betatron in 1946 to become the world’s first synchrotron, is described first. This is followed by a description of the design and construction of the 1 GeV synchrotron at the University of Birmingham which was started in the same year. Finally an account is given of the work of the international team during 1952–3, which formed the basis for the design of the CERN PS before the move to Geneva. It was during this year that John Adams showed the outstanding ability that later brought the project to such a successful conclusion. 1 EARLY PLANS IN BRITAIN: THE WORLD’S FIRST SYNCHROTRON During the second world war Britain’s nuclear physicists were deployed in research directed towards winning the war. Many were engaged in developments associated with radar, (or ‘radiolocation’ as it was then called), both at universities and at government laboratories, such as the radar establishments TRE and ADRDE at Malvern. Others contributed to the atomic bomb programme, both in the UK, and in the USA. Towards the end of the war, when victory seemed assured, the nuclear physicists began looking towards the peacetime future. The construction of new particle accelerators to achieve ever higher energies was seen as one of the more important possibilities. Those working at Berkeley on the electromagnetic separator were familiar with the accelerators there, and following the independent invention (or discovery?) there of the principle of phase stability by Edwin McMillan in 1945, exciting possibilities were immediately apparent [4]. -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

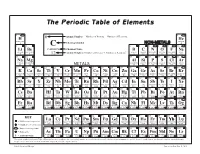

The Periodic Table of Elements

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

MASTER NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C 1983

OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGES IN C0NP 830214 RESEARCH WITH TRANSPLUTONIUM ELEMENTS DE85 010852 Board on Chemical Sciences and Technology Committee on Nuclear and Radlochemistry Commission on Physical Sciences, Mathematics, and Resources National Research Council DISCLAIMER This iw.oort was prepared as an account of work spcnsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsi- bility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any infonnation, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Refer- ence herein to any specific commercial product, process, or scivice by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recom- mendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. MASTER NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS Washington, D.C 1983 DISTBIBUHOU OF THIS DOCUMENT IS Workshop Steering Committee Gerhart Friedlander, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Chairman Gregory R. Choppin, Florida State University Richard L. Hoff, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Darleane C. Hoffman, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Ex-Officio James A. Ibers, Northwestern University Robert A. Penneman, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory Thomas G. Spiro, Princeton University Henry Taube, Stanford University Joseph Weneser, Brookhaven National Laboratory Raymond G. Wymer, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Ex-Officio NRC Staff William Spindel, Executive Secretary Peggy J. Posey, Staff Associate Robert M. -

Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science

Nuclear Science—A Guide to the Nuclear Science Wall Chart ©2018 Contemporary Physics Education Project (CPEP) Appendix E Nobel Prizes in Nuclear Science Many Nobel Prizes have been awarded for nuclear research and instrumentation. The field has spun off: particle physics, nuclear astrophysics, nuclear power reactors, nuclear medicine, and nuclear weapons. Understanding how the nucleus works and applying that knowledge to technology has been one of the most significant accomplishments of twentieth century scientific research. Each prize was awarded for physics unless otherwise noted. Name(s) Discovery Year Henri Becquerel, Pierre Discovered spontaneous radioactivity 1903 Curie, and Marie Curie Ernest Rutherford Work on the disintegration of the elements and 1908 chemistry of radioactive elements (chem) Marie Curie Discovery of radium and polonium 1911 (chem) Frederick Soddy Work on chemistry of radioactive substances 1921 including the origin and nature of radioactive (chem) isotopes Francis Aston Discovery of isotopes in many non-radioactive 1922 elements, also enunciated the whole-number rule of (chem) atomic masses Charles Wilson Development of the cloud chamber for detecting 1927 charged particles Harold Urey Discovery of heavy hydrogen (deuterium) 1934 (chem) Frederic Joliot and Synthesis of several new radioactive elements 1935 Irene Joliot-Curie (chem) James Chadwick Discovery of the neutron 1935 Carl David Anderson Discovery of the positron 1936 Enrico Fermi New radioactive elements produced by neutron 1938 irradiation Ernest Lawrence -

February 2020 Newsletter Manhattan Project NHP Oak Ridge

National Park Service February 2020 Department of the Interior Manhattan Project National Historical Park Oak Ridge, Tennessee Manhattan Project History in February Visit Inside the Oak Ridge Turnpike Gatehouse on Sat- Philip Abelson began working on uranium enrichment urday, February 8 at 3:30 pm (ET). Rangers will host the using liquid thermal diffusion in February of 1941. How- popular “Secrecy, Security, and Spies” program at the Turn- ever construction of his thermal diffusion plant in Phila- pike Gatehouse. The program will begin at 3:30 pm (ET) giv- delphia did not begin until January 1944. This same pro- ing visitors some insight to what life was like in Oak Ridge cess would be used later at the S-50 plant in Oak Ridge, during the Manhattan Project with the need for secrecy, all TN. of the security that surrounded the city, and the threat of Glenn Seaborg and his research group discovered Pluto- spies. The Turnpike Gatehouse is located at 2900 Oak Ridge nium while working at the University of California, Berke- Turnpike, Oak Ridge, TN 37830. ley on February 24, 1941. Construction of the -Y 12 Ura- Join a Park Ranger for a nium enrichment facilities and “Manhattan Project in Pop the X-10 Graphite Reactor be- Culture” on Saturday, Febru- gan in February 1943. Stone ary 22 at 3 pm (ET) at the Ameri- and Webster Engineering was can Museum of Science & Energy, in charge of Y-12 construction 115 East Main Street, Oak Ridge. while DuPont handled X-10. We will lead a discussion of the One year after construction Y- impact the Project had on popu- 12 sent 200 grams of uranium- lar culture in movies, music and 235 to Los Alamos, NM in Feb- television. -

Science Loses Some Friends Francis Crick, Thomas Gold, and Philip Abelson

Monthly Planet October 2004 Science Loses Some Friends Francis Crick, Thomas Gold, and Philip Abelson By Iain Murray he scientifi c world lost three impor- Throughout his career, Abelson used which suggests that the universe and Ttant fi gures in recent weeks, as scientifi c principles to determine genu- the laws of physics have always existed Francis Crick, Thomas Gold, and Philip ine new developments from hype and in the same, steady state. This has since Abelson have all passed away. In their publicity stunts (he was famously dis- been supplanted as the dominant cos- careers, each demonstrated the best that missive of the scientifi c value of the race mological paradigm by the Big Bang science has to offer humanity. Their loss to the moon). In that, he should prove a theory. illustrates how much worse off the state role model for true scientists. After working at the Royal Greenwich of science is today than during their Observatory, Gold moved to the United glory years. Thomas Gold States to become Professor of Astron- Astronomer Thomas Gold had an omy at Harvard. From there he moved Philip Abelson equally distinguished career, in fi elds as to Cornell, where he demonstrated that Philip Abelson was a scientist of truly diverse as engineering, physiology, and the newly discovered “pulsar” phenom- broad talents. One of America’s fi rst cosmology; and he was never afraid of enon must contain a rotating neutron nuclear physicists, he discovered the being called a maverick. A fellow of both star (a star more massive than the sun element Neptunium and designed the the Royal Society and the National Acad- but just 10 km in diameter). -

Atomic Properties of the Elements

P E R I O D I C T A B L E Group 1 18 IA Atomic Properties of the Elements VIIIA 2 1 S FREQUENTLY USED FUNDAMENTAL PHYSICAL CONSTANTS§ S 1 1/2 Physical Measurement Laboratory www.nist.gov/pml 2 0 1 second = 9 192 631 770 periods of radiation corresponding to the H transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of 133Cs Standard Reference Data www.nist.gov/srd He 1 Hydrogen −1 § For the most accurate Helium speed of light in vacuum c 299 792 458 m s (exact) values of these and 1.008* −34 4.002602 2 1s 2 Planck constant h 6.626 070 x 10 J s ( ħ /2 ) other constants, visit 13 14 15 16 17 1s −19 13.5984 IIA elementary charge e 1.602 177 x 10 C physics.nist.gov/constants IIIA IVA VA VIA VIIA 24.5874 −31 2 1 electron mass me 9.109 384 x 10 kg 2 3 4 3 2 1 3 S1/2 4 S0 2 5 P°1/2 6 P0 7 S3/2° 8 P2 9 P3/2° 10 S0 mec 0.510 999 MeV −27 Solids Li Be proton mass mp 1.672 622 x 10 kg B C N O F Ne 2 Lithium Beryllium fine-structure constant 1/137.035 999 Liquids Boron Carbon Nitrogen Oxygen Fluorine Neon 6.94* 9.0121831 −1 10.81* 12.011* 14.007* 15.999* 18.99840316* 20.1797 Rydberg constant R 10 973 731.569 m 2 2 2 Gases 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 2 2 4 2 2 5 2 2 6 15 1s 2s 2p 1s 2s 1s 2s 1s 2s 1s 2s 1s 2s 1s 2s R c 3.289 841 960 x 10 Hz 2p 2p 1s 2s 2p 2p 2p 5.3917 9.3227 Artificially 8.2980 11.2603 14.5341 13.6181 17.4228 21.5645 R hc 13.605 693 eV 2 1 -19 Prepared 2 3 4 3 2 1 11 S1/2 12 S0 electron volt eV 1.602 176 6 x 10 J 13 P1/2° 14 P0 15 S3/2° 16 P2 17 P3/2° 18 S0 −23 −1 Boltzmann constant k 1.380 65 x 10 J K −1 −1 Na Mg molar gas constant -

Quest for Superheavy Nuclei Began in the 1940S with the Syn Time It Takes for Half of the Sample to Decay

FEATURES Quest for superheavy nuclei 2 P.H. Heenen l and W Nazarewicz -4 IService de Physique Nucleaire Theorique, U.L.B.-C.P.229, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Department ofPhysics, University ofTennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996 3Physics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 4Institute ofTheoretical Physics, University ofWarsaw, ul. Ho\.za 69, PL-OO-681 Warsaw, Poland he discovery of new superheavy nuclei has brought much The superheavy elements mark the limit of nuclear mass and T excitement to the atomic and nuclear physics communities. charge; they inhabit the upper right corner of the nuclear land Hopes of finding regions of long-lived superheavy nuclei, pre scape, but the borderlines of their territory are unknown. The dicted in the early 1960s, have reemerged. Why is this search so stability ofthe superheavy elements has been a longstanding fun important and what newknowledge can it bring? damental question in nuclear science. How can they survive the Not every combination ofneutrons and protons makes a sta huge electrostatic repulsion? What are their properties? How ble nucleus. Our Earth is home to 81 stable elements, including large is the region of superheavy elements? We do not know yet slightly fewer than 300 stable nuclei. Other nuclei found in all the answers to these questions. This short article presents the nature, although bound to the emission ofprotons and neutrons, current status ofresearch in this field. are radioactive. That is, they eventually capture or emit electrons and positrons, alpha particles, or undergo spontaneous fission. Historical Background Each unstable isotope is characterized by its half-life (T1/2) - the The quest for superheavy nuclei began in the 1940s with the syn time it takes for half of the sample to decay. -

Chair's Message Making Chemical Testing Relevant to Breast Cancer

Newsletter February 2011 Santa Clara Valley Section American Chemical Society Volume 33 No. 2 FEBRUARY 2011 NEWSLETTER TOPICS March Dinner Meeting • March Dinner Meeting: Making Making Chemical Testing Chemical Testing Relevant to Breast Cancer Relevant to Breast Cancer • Chair’s Message Dr. Megan R. Schwarzman • February Dinner Meeting: Sex, Love Abstract ductive environmental health, and Oxytocin Although breast cancer is U.S. and European chemicals one of the leading causes of can- policy, and the implications for • Welcome to the Santa Clara Valley cer and death in women, even human health and the environ- Section of ACS the small numbers of chemicals ment of the production, use and • New Members List for December that undergo safety testing are disposal of chemicals and prod- • Volunteer with Kids and Chemistry not routinely evaluated for their ucts. She is a research scientist at impacts on mammary (breast) the Center for Occupational and • Black History Month tissue. Likewise, there is no well- Environmental Health (COEH), • Committee Chair Needed established set of tests for screen- in UC Berkeley’s School of Public • Albert Ghiorso, Nuclear Researcher ing chemicals for their ability to raise the risk Health, and Associate Director of Health and • SPLASH is Coming to Stanford of breast cancer. Environment for the interdisciplinary In 2010, Dr. Schwarzman served as continued on next page Principal Investigator of a project to tackle this Chair's Message issue. The Breast Cancer and Chemicals Policy project, supported by a grant from the March Dinner Meeting As I write this, California Breast Cancer Research Program, Joint Meeting with Palo Alto AWIS we’ve just experi- convened a panel of 20 scientists and policy enced a New Year experts to review the biological mechanisms Date: Wednesday, March 23, 2011 celebration and associated with breast cancer and propose a Time: 7:00 Networking Dinner jumped into the strategy for screening and identifying chemi- 7:30-7:45 Announcements International Year of cals that could increase the risk of the disease. -

Ija, LLP Alan D

20-12212-mew Doc 1196 Filed 05/07/21 Entered 05/07/21 21:22:15 Main Document Pg 1 of 74 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK -----------------------------------------------------------------------x : In re: : Chapter 11 : GARRETT MOTION INC., et al.,1 : Case No. 20-12212 (MEW) : Debtors. : (Jointly Administered) : -----------------------------------------------------------------------x CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE I, Rossmery Martinez, depose and say that I am employed by Kurtzman Carson Consultants LLC (KCC), the claims and noticing agent for the Debtors in the above-captioned case. On May 4, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of KCC caused to be served the following document via Electronic Mail upon the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A; and via First Class Mail upon the service list attached hereto as Exhibit B: Notice of June Omnibus Hearing Date [Docket No. 1192] Furthermore, on May 4, 2021, at my direction and under my supervision, employees of KCC caused to be served the following document via Electronic Mail upon the service list attached hereto as Exhibit A; and via First Class Mail upon the service lists attached hereto as Exhibit B and Exhibit C: (Continued on Next Page) 1 The last four digits of Garrett Motion Inc.’s tax identification number are 3189. Due to the large number of debtor entities in these Chapter 11 Cases, which are being jointly administered, a complete list of the Debtors and the last four digits of their federal tax identification numbers is not provided herein. A complete list of such information may be obtained on the website of the Debtors’ claims and noticing agent at http://www.kccllc.net/garrettmotion.