Cornell Notes World War II to 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

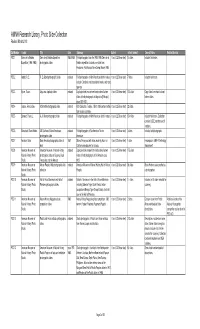

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013 Call Number Creator Title Date Summary Extent Extent (format) General Notes Related Archival PSC 1 Cerro de la Neblina Cerro de la Neblina Expedition 1984-1989 Field photographs from the 1984-1985 Cerro de la 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 14 slides Includes field notes. Expedition (1984-1985) photographic slides Neblina expedition. Includes one slide from Amazonas, Rio Mavaca Base Camp, March 1989. PSC 2 Abbott, R. E. R. E. Abbott photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature, 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 7 slides Includes field notes. includes Cardinals, red-shouldered hawks, and song sparrow. PSC 3 Byron, Oscar. Abyssinia duplicate slides undated Duplicate slides made from hand-colored lantern 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 100 slides Copy slides from hand colored slides of field photographs in Abyssinia [Ethiopia] lantern slides. circa 1920-1921. PSC 4 Jaques, Francis Lee. ACA textile photographic slides undated ACA Collection. Textiles, 15th to 18th century textiles 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 22 slides from various countries. PSC 5 Bierwert, Thane L. A. A. Allen photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature. 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 154 slides Includes field notes. Collection contains USDE numbers and K numbers. PSC 6 Blanchard, Dean Hobbs. AG Southwest Native Americans undated Field photographs of Southwestern Native 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 3 slides Includes field photographs. photographic slides Americans PSC 7 Amadon, Dean Dean Amadon photographic slides of 1957 Slide of fence post with holes made by Acorn or 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 1 slide Fence post in AMNH Ornithology birds California woodpecker for storage. -

Kansas Alumni Magazine

,0) Stormwatch THE FLYING JAYHAWKS AND ALUMNI HOLIDAYS PRESENT CRUISE THE PASSAGE OF PETER THE GREAT AUGUST 1 - AUGUST 14, 1991 Now, for the first time ever, you can follow in the historic pathways of Peter the Great, the powerful Russian czar, as you cruise from Leningrad, Peter's celebrated capital and "window on the West," all the way to Moscow ... on the waterways previously accessible only to Russians. See the country as Peter saw it, with its many treasures still beautifully preserved and its stunning scenery virtually untouched. Come join us as we explore the Soviet Union's bountiful treas- ures and traditions amidst today's "glasnost" and spirit of goodwill. From $3,295 per person from Chicago based on double occupancy CRUISE GERMANY'S MAGNIFICENT EAST ON THE ELBE JULY 27 - AUGUST 8, 1991 A new era unfolds... a country unites ... transition is underway in the East ... Germany's other great river, The Elbe, beckons for the first time in 45 years! Be a part of history! This landmark cruise is a vision that has taken years to realize. Reflected in the mighty Elbe's tranquil waters are some of the most magnificent treasures of the world: renaissance palaces, spired cathedrals, ancient castles... all set amidst scenery so beautiful it will take your breath away! Add to this remarkable cruise, visits to two of Germany's favorite cities, Hamburg and Berlin, and the "Golden City" of Prague, and you have a trip like none ever offered before. From $3,795 per person from Chicago based on double occupancy LA BELLE FRANCE JUNE 30-JULY 12, 1991 There is simply no better way to describe this remarkable melange of culture and charm, gastronomy and joie de vivre. -

KANSAS ALUMNI MAGAZINE3 a Hot Tin Roof

VOL. 69 TVo. 4 KANSAMAGAZINS ALUMNE I \ •Jl THE FLYING JAYHAWKS AND ALUMNI HOLIDAYS PRESENT CRUISE THE PASSAGE OF PETER THE GREAT AUGUST 1 - AUGUST 14, 1991 Now, for the first time ever, you can follow in the historic pathways of Peter the Great, the powerful Russian czar, as you cruise from Leningrad, Peter's celebrated capital and "window on the West," all the way to Moscow ... on the waterways previously accessible only to Russians. See the country as Peter saw it, with its many treasures still beautifully preserved and its stunning scenery virtually untouched. Come join us as we explore the Soviet Union's bountiful treas- ures and traditions amidst today's "glasnost" and spirit of goodwill. From $3,295 per person from Chicago based on double occupancy CRUISE GERMANY'S MAGNIFICENT EAST ON THE ELBE JULY 27 - AUGUST 8, 1991 A new era unfolds ... a country unites ... transition is underway in the East ... Germany's other great river, The Elbe, beckons for the first time in 45 years! Be a part of history! This landmark cruise is a vision that has taken years to realize. Reflected in the mighty Elbe's tranquil waters are some of the most magnificent treasures of the world: renaissance palaces, spired cathedrals, ancient castles ... all set amidst scenery so beautiful it will take your breath away! Add to this remarkable cruise, visits to two of Germany's favorite cities, Hamburg and Berlin, and the "Golden City" of Prague, and you have a trip like none ever offered before. From $3,795 per person from Chicago based on double occupancy LA BELLE FRANCE JUNE 30-JULY 12, 1991 There is simply no better way to describe this remarkable melange of culture and charm, gastronomy and joie de vivre. -

'54 Class Notes Names, Topics, Months, Years, Email: Ruth Whatever

Use Ctrl/F (Find) to search for '54 Class Notes names, topics, months, years, Email: Ruth whatever. Scroll up or down to May - Dec. '10 Jan. – Dec. ‘16 Carpenter Bailey: see nearby information. Click Jan. - Dec. ‘11 Jan. - Dec. ‘17 [email protected] the back arrow to return to the Jan. – Dec. ‘12 Jan. - Dec. ‘18 or Bill Waters: class site. Jan. – Dec ‘13 July - Dec. ‘19 [email protected] Jan. – Dec. ‘14 Jan. – Dec. ‘20 Jan. – Dec. ‘15 Jan. – Aug. ‘21 Class website: classof54.alumni.cornell.edu July 2021 – August 2021 Since this is the last hard copy class notes column we will write before CAM goes digital, it is only fitting that we received an e-mail from Dr Bill Webber (WCMC’60) who served as our class’s first correspondent from 1954 to 1959. Among other topics, Webb advised that he was the last survivor of the three “Bronxville Boys” who came to Cornell in 1950 from that village in Westchester County. They roomed together as freshmen, joined Delta Upsilon together and remained close friends through graduation and beyond. They even sat side by side in the 54 Cornellian’s group photo of their fraternity. Boyce Thompson, who died in 2009, worked for Pet Milk in St. Louis for a few years after graduation and later moved to Dallas where he formed and ran a successful food brokerage specializing in gourmet mixed nuts. Ever the comedian, his business phone number (after the area code) was 223-6887, which made the letters BAD-NUTS. Thankfully, his customers did not figure it out. -

Bear in Mind

Bear in Mind Test your East Hill IQ with the ultimate Big Red trivia quiz How Will You Score? 100 points: Top of the Tower 90+ Excellent Ezra 80+ Marvelous Martha 70+ Awesome Andrew 60+ Classy Cayuga 50+ OK Okenshields <50 Slippery Slope ND20_trivia_PROOF_4_JBOKrr2.indd 54 11/3/20 4:00 PM Are you an aficionado of Cornell lore? Do you know how many people were in the fi rst graduating class in 1869 or how many fans can fi t in the Crescent? How Ezra fi gured into a space shuttle launch . and where Superman spent his senior year? Try your hand at CAM’s extravaganza of Big Red factoids—then check the answers on page 90 and see how you did! 1. The First General 6. Approximately how many 8. What Ancient Greek hero Announcement of Cornell’s hours did the 1969 Straight is immortalized in a statue, founding stated that “all takeover last? made of chrome car bumpers, candidates for admission to a) Twenty-four outside the Statler Hotel? any department or course b) Thirty-six a) Achilles must present satisfactory c) Forty-eight b) Odysseus evidences” of what? d) Sixty c) Heracles a) A s econdary school d) Perseus education or its equivalent 7. What year was the Student b) Being at least s eventeen Homophile League—only the 9. How many steps are there years o f age second gay rights group ever to the top of McGraw Tower? c) Good moral character organized on a U.S. college a) 151 d) Sound physical health campus—founded on the Hill? b) 161 a) 1965 c) 171 2. -

The American Museum of Natural History

THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT JULY, 1953, THROUGH JUNE, 1954 THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT JULY, 1953, THROUGH JUNE, 1954 THE CITY OF NEW YORK 1954 EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT To the Trustees of The American Museum of Natural History and to the Municipal Authorities of the City of New York THE Museum's fiscal year, which ended June 30, 1954, was a good one. As in our previous annual report, I believe we can fairly state that continuing progress is being made on our long-range plan for the Museum. The cooperative attitude of the scientific staff and of our other employees towards the program set forth by management has been largely responsible for what has been accomplished. The record of both the Endowment and Pension Funds during the past twelve months has been notably satisfactory. In a year of wide swings of optimism and pessimism in the security markets, the Finance Committee is pleased to report an increase in the market value of the Endowment Fund of $3,011,800 (87 per cent of which has been due to the over-all rise in prices and 13 per cent to new gifts). Common stocks held by the fund increased in value approximately 30 per cent in the year. The Pension Fund likewise continued to grow, reaching a valuation of $4,498,600, as compared to $4,024,100 at the end of the previous year. Yield at cost for the Endow- ment Fund as of July 1 stood at 4.97 per cent and for the Pension Fund at 3.74 per cent. -

LSNY Proceedings 54-57, 1941-1945

Nf\- i\l HARVARD UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OF THE Museum of Comparative Zoology \ - .>v 4 _ ' /I 1941-1945 Nos. 54-57 PROCEEDINGS OF THE . LINNAEAN SOCIETY OF NEW YORK For the Four Years Ending March, 1945 Date of Issue, September 16, 1946 J • r'-' ;; :j 1941-1945 Nos. 54-57 PROCEEDINGS OF THE LINNAEAN SOCIETY OF NEW YORK For the Four Years Ending March, 1945 Date of Issue, September 16, 1946 S^t-, .7- Table of Contents Some Critical Phylogenetic Stages Leading to the Flight of Birds William K. Gregory 1 The Chickadee Flight of 1941-1942 Hustace H. Poor 16 The Ornithological Year 1944 in the New York City Region John L. Bull, Jr. 28 Suggestions to the Field Worker and Bird Bander Avian Pathology 36 Collecting Mallophaga 38 General Notes Rare Gulls at The Narrows, Brooklyn, in the Winter of 1943-1944 40 Comments on Identifying Rare Gulls 42 Breeding of the Herring Gull in Connecticut — 43 Data on Some of the Seabird Colonies of Eastern Long Island 44 New York City Seabird Colonies 46 Royal Terns on Long Island 47 A Feeding Incident of the Black-Billed Cuckoo 49 Eastern Long Island Records of the Nighthawk 50 Proximity of Occupied Kingfisher Nests 51 Further Spread of the Prairie Horned Lark on Long Island 52 A Late Black-Throated Warbler 53 Interchange of Song between Blue-Winged and Golden-Winged Warblers 1942- 53 Predation by Grackles 1943- 54 1944- Observations on Birds Relative to the Predatory New York Weasel 56 Clinton Hart Merriam (1855-1942) First President of the Linnaean Society of New York A. -

Commencement Exercises Program, August 10, 1951

iryaut ~nlltgt of ilustnessPusiness A~ministruttnnAhtinistration 1.Eig~ty-tig~t~Eighty-eighth Annual Q!ommrntrmrutMomm~nt~m~nt "UgUllt 1n, 1951 1n o'clock ]lrlrrans' :!1Ilrmorial .Au~itorium Jlrnttibrntr. 1R4nbr lI.alanb ~ MUSICAL PRELUDE Selections from Anderson, Friml, Herbert and Romberg ACADEMIC PROPROCESSION CESSION "Pomp and Circumstance", Elgar and "Triumphal March", Fucik THE NATIONAL ANTHEM INT70CATIONINVOCATION REVEREND FATHER CHARLES H. MCKENNA,McKENNA, a.p.O.P. Providence College GREETINGS OF THE STATE THE HONOURABLE JOHN S. MCKIERNANMcKIERNAN Lieutenant Governor of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations "EDUCA"EDUCATION TION AND THE PRODUCTIVE CITIZEN" DR. EARL JAMES MCGRATH United States Commissioner otof Education SELECTED MUSIC Melodies from "Die Fledermaus", Strauss ADDRESS TO GRADUATES "DARE TO BE DII;I;ERENT''DIFFERENT" DR. HENRY L. JACOBS President of BlyantBryant College PRESENTATION OF CANDIDATES FOR HONORARY DEGREES &a%~ PRESENTATION OF CANDIDATES FOR BACHELORS' DEGREES AND DIPLOMAS DEANS OF THE COLLEGE A WARDING OF DEGREES AND DIPLOMAS PKESIDENTPRESIDENT JACOBS (The(Thc audience is requested not to applaud until the end) PRESENTATION OF PROFESSIONAL TEACHERS' CERTIFICATES DR. MICHAEL F. WALSH CommissionerCommissio~zer of Education of the State of Rhode Island BENEDICTION REVEREND FATHER CHARLES H. MCKENNAMcKENNA RECESSIONAL Music by Felix MendelssolznMendelssohn (The audience is requested to remain standing until all graduates have lcftleft the auditorium) Music by Robert Gray and his orchestra f!;onorary irgrres c&wu~ DOCTOR OF CIVIL LAWS (D.C.L.) DR. EARL JAMES MCGRATH United States Commissioner of Education Dr. McGrath was born in Buffalo.Buffalo, New~ew York. He holds the degrees of Bachelor of Arts and hlasterMaster of Arts from the University of Buffalo and the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from the University of Chicago. -

Trustees 1961 62.Pdf (9.326Mb)

PROCEEDINGS of the BOARD OF TRUSTEES of CORNELL UNIVERSITY INCLUDING THE MINUTES OF CERTAIN STANDING COMMITTEES July 1, 1961 - June 30, 1962 4095 CORNELL UNIVERSITY PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Meeting held Friday, August 18, 1961, 9*30 a.m., Faculty Room, Cornell University Medical College, New York City PRESENT: Vice Chairman Donlon, Trustees Levis, Littlewood, Malott, Scheetz, and Syme. Provost Atwood, Vice President Burton, Controller Peterson, Budget Director McKeegan, and Secretary Stamp. ABSENT: Trustees Cisler, Dean, and Severinghaus. Vice Chairman Donlon called the meeting to order in executive session at 9 :30 a.m. The meeting was reconvened in regular session at 11:15 a.m. 1. APPROVAL OF MINUTES: Voted to approve the minutes of the Executive Committee meeting held June 11, 1961, as previously distributed. 2. PHYSICS-ARPA CONSTRUCTION AUTHORIZATION AND APPRO PRIATION: Voted to authorize the Administration to proceed with the following projects as initial stages of the total project to construct the Physics-ARPA building complex: (l) To construct the analytical facility for the Materials Science Center in some 11,000 sq. ft. of Baker Laboratory basement, at an estimated cost of $400,000, of which $220,000 is presently available in ARPA funds, leaving $180,000 to be financed from other University funds; 4096 8/18/61 Ex> com. (2) To construct temporary space In Rockefeller Hall court to house technical operations, stock room, machine shop, student shop, and increased low temperature facilities to be in continuous operation while the new building is being built (at which time the northeast shop wing of Rockefeller Hall will be demolished)— at an estimated cost of $70,000. -

The Sixty-Seventh Stated Meeting of the American Ornithologists' Union

Vol.1950 67Il PE'FfINGILL,Sixty-seventh Stated Meeting ofA. O. U. 89 THE SIXTY-SEVENTH STATED MEETING OF THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS' UNION BY OLIN SEWALL PETTINGILL, JR., SECRETARY THE first meeting of the Union in Buffalo, New York, was held October 10 to 14, 1949, at the invitation of the Buffalo Ornithological Society and the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences. Headquarters were in the Hotel Statler. Business sessions and the Annual Dinner were held in the hotel; public sessions,exhibits, and a reception were in the Buffalo Museum of Science. BUSINESS SESSIONS Businesssessions were as follows: (1) First Sessionof the Council, Monday, October 10, 10:15 a.m. to 12:15 p.m. Number in attend- ance, 15. (2) SecondSession of the Council, Monday, 1:40 to 4:15 p.m. Number in attendance,15. (3) Meeting of the Fellows,Mon- day, 4:15 to 5:45 p.m. Number in attendance, 26. (4) Meeting of the Fellowsand Members, Monday, 8:15 p.m. to Tuesday, October 11, 1:10 a.m. Number of Fellows present, 26; number of Members present,34. (5) Third Sessionof the Council, Wednesday,October 12, 8:05 to 10:15 a.m. Number in attendance, 15. Reportsof O•cers. The Secretaryreported that the total member- ship of the Union was 2,328 as of October 9, 1949. Membership by classeswas as follows: Fellows, 55; Fellows Emeriti, 1; Honorary Fellows, 13; CorrespondingFellows, 61; Members, 145; Associates, 2,053. Since the last meeting, 718 personshad been proposedfor Associatemembership, their election bringing the total membership to 3,031. -

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments IamdeeplygratefultoErnstMayrwithwhomIcorrespondedsincetheearly 1960s. I was always astonished that despite his busy schedule as Director of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, he would take time to answer my enquiries in detail. I met him at Harvard University in 1968 and discussed aspects of speciation and evolution with him when we met several times in the United States and in Germany in later years. I also thank him for his contributions to this volume and forhispermissiontoreviewmaterialintheMayrPapersattheErnstMayrLibrary (Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University) as well as portions of his correspondence at the Harvard University Archives. During visits to Cambridge and Bedford, Massachusetts in September 2003 and October 2004, we discussed an early version of this manuscript. I was also permitted to use a 12-page manuscript by Margarete (Gretel) Mayr, Ernst’s wife, on “Our life in America during the Second World War.” Their daughters Mrs. Christa Menzel and Mrs. Susanne Mayr Harrison also supplied additional information. Mrs. Harrison mentioned to me details of the family’s frequent visits to Cold Spring Harbor (New York) during the 1940s and Mrs. Menzel and her husband Gerhart Menzel kindly showed me The Farm near Wilton, New Hampshire. Mrs. Harrison also provided prints and electronic files of family photographs and reviewed various parts of the manuscript. I thank the nephews Dr. Otto Mayr and Dr. Jörg Mayr who maintain a family archive in Lindau, Germany, for historical photographs and data regarding the family. Ernst Mayr’s niece Roswitha Kytzia (née Mayr) and her husband Peter Kytzia (Hammersbach near Hanau, Germany), who served as E. Mayr’s main family contact in Germany during the last 20 years, also furthered this project and helped with various information. -

President Emeritus Malott Dies at Age 98

WELCOME HOME Alumni and friends return to campus this weekend and will enjoy a full slate of CORNELL Homecoming events. GOOD FOOD, GOOD MEDICINE Phytochemist finds Uganda's gorillas may self-medicate with bacteria-fighting fruit. Volume 28 Number 5 September 19, 1996 Vet incinerator President Emeritus Malott dies at age 98 permit process is suspended at CD request At the request of Cornell, the permitting process for the replacement incinerator at the university'S College of Veterinary Medi cine has been sus pended by the New York State Depart ment of Environmen tal Conservation (DEC), and the uni versity is invitingcom munity and campus Loew groups to participate in an advisory committee on the project. In response to a number of concerns voiced by community members, Cornell asked the State Uni versity Construction Fund (SUCF), lead Craft agency on the project, to request that the DEC delay the process until additional data on a number of ques tions can be generated and evaluated. The permitting process was halted Aug. 7. Cornell is in the process ofreaching out to . Robert Barker/University Photography community and campus organizationsto join Comell President Emeritus Deane W. Malott acknowledges a Barton Hall audience during inaugural ceremonies a community advisory committee that will for President Hunter Rawlings on Oct. 12, 1995. discuss all aspects of the incinerator issue. Franklin M. Loew, dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine, and Harold D. Craft, Cornell vice president for facilities and cam He is remembered for his energy and vision pus services, will co-chair the committee. "The university is fully willing to enter Deane W.