LSNY Proceedings 54-57, 1941-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

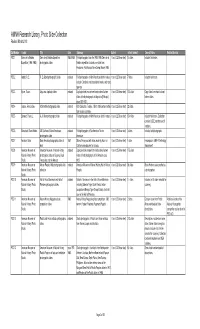

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013 Call Number Creator Title Date Summary Extent Extent (format) General Notes Related Archival PSC 1 Cerro de la Neblina Cerro de la Neblina Expedition 1984-1989 Field photographs from the 1984-1985 Cerro de la 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 14 slides Includes field notes. Expedition (1984-1985) photographic slides Neblina expedition. Includes one slide from Amazonas, Rio Mavaca Base Camp, March 1989. PSC 2 Abbott, R. E. R. E. Abbott photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature, 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 7 slides Includes field notes. includes Cardinals, red-shouldered hawks, and song sparrow. PSC 3 Byron, Oscar. Abyssinia duplicate slides undated Duplicate slides made from hand-colored lantern 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 100 slides Copy slides from hand colored slides of field photographs in Abyssinia [Ethiopia] lantern slides. circa 1920-1921. PSC 4 Jaques, Francis Lee. ACA textile photographic slides undated ACA Collection. Textiles, 15th to 18th century textiles 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 22 slides from various countries. PSC 5 Bierwert, Thane L. A. A. Allen photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature. 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 154 slides Includes field notes. Collection contains USDE numbers and K numbers. PSC 6 Blanchard, Dean Hobbs. AG Southwest Native Americans undated Field photographs of Southwestern Native 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 3 slides Includes field photographs. photographic slides Americans PSC 7 Amadon, Dean Dean Amadon photographic slides of 1957 Slide of fence post with holes made by Acorn or 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 1 slide Fence post in AMNH Ornithology birds California woodpecker for storage. -

Tegument, I Can Only Conclude That This Monograph Fails to Attain Its Stated

REVIEWS EDITED BY JOHN WILLIAM HARDY The Coturnix Quail/anatomy and histology.--Theodore C. Fitzgerald. 1970. Ames, Iowa State Univ. Press. Pp. xix q- 306, many text figures. $?.95.--During the pastseveral decades, the Coturnixor JapaneseQuail (Coturnix½oturnix japonica) has becomea valuable experimentalanimal in many fields of arian biology (see bibliographiesin the "Quail Quarterly"). Much of this researchis physiologicalfor which many workers require some backgroundmorphological information. Realizing the need for a descriptiveanatomy of Coturnix,a groupof workersat Auburn Uni- versity, long a center for Coturnix studies,asked Professor Fitzgerald and his asso- ciatesin the Department of Anatomy and Histology, Schoolof Veterinary Medicine, to undertakesuch a project. UnfortunatelyProfessor Fitzgerald died before it was completed,and membersof his staff finishedthe project and publishedthe mono- graph. As a result,it is not clearwhat part ProfessorFitzgerald had in the research incorporatedin this book and who was responsiblefor many important decisions. Accordingto the Preface,veterinary students made the dissectionsand art students preparedthe first drawings. Mrs. J. Guenther was responsiblefor final work on the illustrationsand the manuscript,and for seeingthe book through publication. But no informationis given on responsibilityfor checkingdissections, identification of structures,terminology, and writing the manuscript.Moreover, Professor Fitzgerald and his associates(mentioned in the Preface) are not known to me as avian ana- tomists,and are not the seniorauthors of any publishedpapers cited in the bibliog- raphy; I presumethat they are mammaliananatomists because of certainterminology used. Further,it seemsreasonable to concludethat this projectwas undertakenby Fitzgerald'sgroup as a favor to their colleaguesat AuburnUniversity, and that it was not relatedto any other researchprojects in their department.Lastly this study had to be completedwithout the guidanceof the originalproject director,which always resultsin increasedpublication difficulties. -

Altriciality and the Evolution of Toe Orientation in Birds

Evol Biol DOI 10.1007/s11692-015-9334-7 SYNTHESIS PAPER Altriciality and the Evolution of Toe Orientation in Birds 1 1 1 Joa˜o Francisco Botelho • Daniel Smith-Paredes • Alexander O. Vargas Received: 3 November 2014 / Accepted: 18 June 2015 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015 Abstract Specialized morphologies of bird feet have trees, to swim under and above the water surface, to hunt and evolved several times independently as different groups have fish, and to walk in the mud and over aquatic vegetation, become zygodactyl, semi-zygodactyl, heterodactyl, pam- among other abilities. Toe orientations in the foot can be prodactyl or syndactyl. Birds have also convergently described in six main types: Anisodactyl feet have digit II evolved similar modes of development, in a spectrum that (dII), digit III (dIII) and digit IV (dIV) pointing forward and goes from precocial to altricial. Using the new context pro- digit I (dI) pointing backward. From the basal anisodactyl vided by recent molecular phylogenies, we compared the condition four feet types have arisen by modifications in the evolution of foot morphology and modes of development orientation of digits. Zygodactyl feet have dI and dIV ori- among extant avian families. Variations in the arrangement ented backward and dII and dIII oriented forward, a condi- of toes with respect to the anisodactyl ancestral condition tion similar to heterodactyl feet, which have dI and dII have occurred only in altricial groups. Those groups repre- oriented backward and dIII and dIV oriented forward. Semi- sent four independent events of super-altriciality and many zygodactyl birds can assume a facultative zygodactyl or independent transformations of toe arrangements (at least almost zygodactyl orientation. -

Phoenix Zoo Program Animal Handling Protocols

Interpretive Animal Resources Animal Handling and Presentation Protocols 2014-2015 Updated: June 21, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2 2. AZA Presentation of Animals Policy 2 3. Animal Handling and Presentation Training and Certification Process 3 4. Program Animal Levels 5 5. Disciplinary Action 7 6. Example: Animal Handling and Presentation Infraction Report 8 7. Emergency Situations 9 a. Emergency Contacts 9 b. Human Injury Protocol 10 c. Animal Injury or Illness Protocol 10 d. Animal Escape 10 e. Animal Death 10 8. Animal “Sense” 11 9. Safety 11 a. The Three L’s 11 b. Zoonotic Diseases 11 i. TB Testing 11 ii. Off Programs 11 iii. Cold/Flu Symptoms 11 iv. Quarantine 11 v. Hand Washing 12 vi. Dress Code and Grooming 12 vii. Cleaning Presentation Area 12 viii. Food and Beverages 12 ix. Smoking 12 10. Animal Requests and Reservations 13 a. When To Work 13 b. Animals for Personal Use 13 11. Collecting Animals for Programs 14 a. Tags 15 b. Equipment 15 c. Animal Care Kits 16 12. Transporting Animals 16 13. Temperature and Weather Guidelines 17 14. Presenting Animals in Programs 18 a. Presentation Environment 18 b. Stress 18 c. Basic Handling Methods 18 d. Water 18 e. Animal Diet 18 f. Handling Order 19 g. Proximity to Other Animals 19 h. Animal Supervision 19 i. Public Fear of Animals 19 j. Touching Animals 19 k. Handler Discretion 19 15. Approved Presentation Areas on Zoo Grounds 20 16. Returning Animals from Programs 20 17. Communication and Daily Section Reports (DSR) 21 18. Example: Program Daily Section Report 22 19. -

Òðàíñôîðìàöèè Ñòîïû Â Ðàííåé Ýâîëþöèè Ïòèö

Vestnik zoologii, 34(4—5): 123—127, 2000 © 2000 И. А. Богданович ÓÄÊ 591.4+575.4 : 598.2 ÒÐÀÍÑÔÎÐÌÀÖÈÈ ÑÒÎÏÛ Â ÐÀÍÍÅÉ ÝÂÎËÞÖÈÈ ÏÒÈÖ È. À. Áîãäàíîâè÷ Èíñòèòóò çîîëîãèè ÍÀÍ Óêðàèíû, óë. Á. Õìåëüíèöêîãî, 15, Êèåâ-30, ÃÑÏ, 01601 Óêðàèíà Ïîëó÷åíî 5 ÿíâàðÿ 2000 Òðàíñôîðìàöèè ñòîïû â ðàííåé ýâîëþöèè ïòèö. Áîãäàíîâè÷ È. À. – Íåäàâíÿÿ íàõîäêà Protoavis texen- sis (Chatterjee, 1995) îòîäâèãàåò âðåìÿ ïðîèñõîæäåíèÿ ïòèö ê òðèàñó è ñâèäåòåëüñòâóåò â ïîëüçó òåêî- äîíòíîãî ïòè÷üåãî ïðåäêà. Íåñìîòðÿ íà ïåðåõîä ê áèïåäàëèçìó, òåêîäîíòû èìåëè ïÿòèïàëóþ ñòîïó. Ñîõðàíåíèå õîðîøî ðàçâèòîãî è îòâåäåííîãî â ñòîðîíó 1-ãî ïàëüöà ñ äàëüíåéøèì åãî ðàçâîðîòîì íà- çàä ìîãëî áûòü ñåëåêòèâíûì ïðèçíàêîì áëàãîäàðÿ äâóì ôóíêöèîíàëüíî-ñåëåêòèâíûì ñëåäñòâèÿì. Âî- ïåðâûõ, îòñòàâëåííûé íàçàä íèçêîðàñïîëîæåííûé ïåðâûé ïàëåö ñëóæèë ýôôåêòèâíîé çàäíåé îïîðîé, ÷òî áûëî âàæíî â ïåðèîä ñòàíîâëåíèÿ áèïåäàëèçìà, ñâÿçàííîãî ñ «ïåðåóñòàíîâêîé» öåíòðà òÿæåñòè òåëà. Ýòî îò÷àñòè ðàçãðóæàëî îò îïîðíîé ôóíêöèè òÿæåëûé õâîñò (õàðàêòåðíûé äëÿ òåêîäîíòîâ â öå- ëîì) áëàãîïðèÿòñòâóÿ åãî ðåäóêöèè. Âî-âòîðûõ, óêàçàííîå ñòðîåíèå ñòîïû (èìåííî òàêîå îïèñàíî ó Protoavis) îáåñïå÷èâàëî ýôôåêòèâíîå âûïîëíåíèå õâàòàòåëüíîé ôóíêöèè. Òàêèì îáðàçîì, ïðåäïîëà- ãàåìàÿ «ïðåäïòèöà» áûëà ñïîñîáíà ïåðåäâèãàòüñÿ êàê ïî çåìëå, òàê è ïî âåòâÿì ñ îáõâàòûâàíèåì ïî- ñëåäíèõ èìåííî òàçîâûìè, à íå ãðóäíûìè, êàê ïðåäïîëàãàëîñü, êîíå÷íîñòÿìè. Ê ë þ ÷ å â û å ñ ë î â à : ïòèöû, ýâîëþöèÿ, òàçîâàÿ êîíå÷íîñòü. Foot Transformations in Early Evolution of Birds. Bogdanovich I. A. – Recent find of Protoavis texen- sis (Chatterjee, 1995) shifts the avian origin time to the Trias and support a hypothesis of a thecodontian avian ancestor. In spite of bipedalism thecodonts had a five digits foot. Preservation of well developed and abducted hallux with its farther reversing could be selective because of two functional sequences. -

Gerhard Heilmann Og Teorierne Om Fuglenes Oprindelse

Gerhard Heilmann gav DOF et logo længe før ordet var opfundet de Viber, som vi netop med dette nr har forgrebet os på og stiliseret. Ude i verden huskes han imidlertid af en helt anden grund. Gerhard Heilmann og teorierne om fuglenes oprindelse SVEND PALM Archaeopteryx og teorierne I årene 1912 - 1916 bragte DOFT fem artikler, som fik betydning for spørgsmålet om fuglenes oprindelse. Artiklerne var skrevet af Gerhard Heilmann og havde den fælles titel »Vor nuvæ• rende Viden om Fuglenes Afstamning«. Artiklerne tog deres udgangspunkt i et fossil, der i 1861 og 1877 var fundet ved Solnhofen nær Eichstatt, og som fik det videnskabelige navn Archaeopteryx. Dyret var på størrelse med en due, tobenet og havde svingfjer og fjerhale, men det havde også tænder, hvirvelhale og trefingrede forlemmer med klør. Da Archaeopteryx-fundene blev gjort, var der kun gået få årtier, siden man havde fået det første kendskab til de uddøde dinosaurer, af hvilke nog le var tobenede og meget fugleagtige. Her kom da Archaeopteryx, der mest lignede en dinosaur i mini-format, men som med sine fjervinger havde en tydelig tilknytning til fuglene, ind i billedet (Fig. 1). Kort forinden havde Darwin (1859) med sit værk »On the Origin of Species« givet et viden Fig. 1. Archaeopteryx. Fra Heilmann (1926). skabeligt grundlag for udviklingslæren, og Ar chaeopteryx kom meget belejligt som trumfkort for Darwins tilhængere, som et formodet binde led mellem krybdyr og fugle. gernes og flyveevnens opståen. I den nulevende I begyndelsen hæftede man sig især ved lighe fauna findes adskillige eksempler på dyr med en derne mellem dinosaurer, Archaeopteryx og fug vis flyveevne, f.eks. -

Bulletin Published Quarterly

BULLETIN PUBLISHED QUARTERLY September, 1988 No. 3 COMMENTS ON THE WING SHAPE OF THE HYPOTHETICAL PROAVIAN James McAllister The origin of avian flight has been debated since Williston (1879) and Marsh (1880) proposed the competing cursorial and arboreal theories, respectively (reviews in Ostrom 1979 and Feduccia 1980). In the arboreal theory, powered flight evolved in a climbing proavian (hypothetical avian precursor) that glided from trees. The cursorial theory proposes that the transition to powered flight was via a ground-dwelling, running proavian. Unfortunately, the fossil record is sparse for the early stages of bird evolution. Archaeopteryx and the Triassic fossil discovered and identified as a bird by Sankar Chat- terjee are the two oldest forms. Although geologically older, the Triassic fossil has not been described, evaluated, and put into the context of avian evolution at this time and so the functional stage prior to Archaeopteryx remains pre-eminent in the reconstruction of avian flight. I present the hypothesis that the arboreal proavian wing had a low aspect ratio (Figure 1) and thus was the primitive condition for birds. I also comment on prior discussions of the wing shape of an arboreal proavis, including those by Saville (1957) and Peterson (1985), and suggest refinements for reconstructions by Boker (1935) and Tarsitano (1985). -length- Aspect Ratio = width = Figure 1. (A) A silhouette of Archaeopteryx (after Heilmann 1927, fig. 141) which has a wing with a low aspect ratio - short length and wide breadth. (B) An albatross silhouette has a high aspect ratio wing - longer length compared to breadth - and is better suited for gliding. -

Phylogeny and Avian Evolution Phylogeny and Evolution of the Aves

Phylogeny and Avian Evolution Phylogeny and Evolution of the Aves I. Background Scientists have speculated about evolution of birds ever since Darwin. Difficult to find relatives using only modern animals After publi cati on of “O rigi i in of S peci es” (~1860) some used birds as a counter-argument since th ere were no k nown t ransiti onal f orms at the time! • turtles have modified necks and toothless beaks • bats fly and are warm blooded With fossil discovery other potential relationships! • Birds as distinct order of reptiles Many non-reptilian characteristics (e.g. endothermy, feathers) but really reptilian in structure! If birds only known from fossil record then simply be a distinct order of reptiles. II. Reptile Evolutionary History A. “Stem reptiles” - Cotylosauria Must begin in the late Paleozoic ClCotylosauri a – “il”“stem reptiles” Radiation of reptiles from Cotylosauria can be organized on the basis of temporal fenestrae (openings in back of skull for muscle attachment). Subsequent reptilian lineages developed more powerful jaws. B. Anapsid Cotylosauria and Chelonia have anapsid pattern C. Syypnapsid – single fenestra Includes order Therapsida which gave rise to mammalia D. Diapsida – both supppratemporal and infratemporal fenestrae PttPattern foun did in exti titnct arch osaurs, survi iiving archosaurs and also in primitive lepidosaur – ShSpheno don. All remaining living reptiles and the lineage leading to Aves are classified as Diapsida Handout Mammalia Extinct Groups Cynodontia Therapsida Pelycosaurs Lepidosauromorpha Ichthyosauria Protorothyrididae Synapsida Anapsida Archosauromorpha Euryapsida Mesosaurs Amphibia Sauria Diapsida Eureptilia Sauropsida Amniota Tetrapoda III. Relationshippp to Reptiles Most groups present during Mesozoic considere d ancestors to bird s. -

ETD Template

EXPLAINING EVOLUTIONARY INNOVATION AND NOVELTY: A HISTORICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL STUDY OF BIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS by Alan Christopher Love BS in Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1995 MA in Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2002 MA in Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, 2004 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 2005 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Alan Christopher Love It was defended on June 22, 2005 and approved by Sandra D. Mitchell, PhD Professor of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Pittsburgh Robert C. Olby, PhD Professor of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Pittsburgh Rudolf A. Raff, PhD Professor of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington Günter P. Wagner, PhD Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Yale University James G. Lennox, PhD Dissertation Director Professor of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Pittsburgh ii Copyright by Alan Christopher Love 2005 iii EXPLAINING EVOLUTIONARY INNOVATION AND NOVELTY: A HISTORICAL AND PHILOSOPHICAL STUDY OF BIOLOGICAL CONCEPTS Alan Christopher Love, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2005 Abstract Explaining evolutionary novelties (such as feathers or neural crest cells) is a central item on the research agenda of evolutionary developmental biology (Evo-devo). Proponents of Evo- devo have claimed that the origin of innovation and novelty constitute a distinct research problem, ignored by evolutionary theory during the latter half of the 20th century, and that Evo- devo as a synthesis of biological disciplines is in a unique position to address this problem. -

The American Museum of Natural History

THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT JULY, 1953, THROUGH JUNE, 1954 THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT JULY, 1953, THROUGH JUNE, 1954 THE CITY OF NEW YORK 1954 EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT To the Trustees of The American Museum of Natural History and to the Municipal Authorities of the City of New York THE Museum's fiscal year, which ended June 30, 1954, was a good one. As in our previous annual report, I believe we can fairly state that continuing progress is being made on our long-range plan for the Museum. The cooperative attitude of the scientific staff and of our other employees towards the program set forth by management has been largely responsible for what has been accomplished. The record of both the Endowment and Pension Funds during the past twelve months has been notably satisfactory. In a year of wide swings of optimism and pessimism in the security markets, the Finance Committee is pleased to report an increase in the market value of the Endowment Fund of $3,011,800 (87 per cent of which has been due to the over-all rise in prices and 13 per cent to new gifts). Common stocks held by the fund increased in value approximately 30 per cent in the year. The Pension Fund likewise continued to grow, reaching a valuation of $4,498,600, as compared to $4,024,100 at the end of the previous year. Yield at cost for the Endow- ment Fund as of July 1 stood at 4.97 per cent and for the Pension Fund at 3.74 per cent. -

BIRD TRACKS Woodsmoke

Photography by Peter Skillen Peter by Photography GETTING STARTED WITH TRACKING By Ben McNutt BIRD TRACKS Woodsmoke READ BEN’S FULL BIO NOW AT THEBUSHCRAFTJOURNAL.COM www.woodsmoke.uk.com 00 | THEBUSHCRAFTJOURNAL.COM he easiest way to get to grips with bird tracks is to learn about the feet that make them and the fascinating diversity in their skeletal structures and morphology. It is said that ‘form follows function’ and bird foot morphology is no exception, as the structure relates directly to lifestyle demands of the bird. Types of bird tracks Most of the bird tracks you will encounter will be Tetradactyl, meaning they have four digits on each foot. The etymological root of the word 1. Anisodactyl coming from the Greek word ‘tetra’, meaning ‘four’ and the word ‘dactyl’ 2. Raptorial meaning ‘fnger’ or ‘digit’. 3. Syndactyl 4. Tridactyl For simplicity trackers number the toes on each foot and as with 5. Palmate mammals, ‘toe one’ is the big toe / thumb (or hallux). For most birds the 6. Semi-palmate hallux is like an opposable thumb and points backwards, which allows 7. Totipalmate the bird to perch and grip branches. The toes are then subsequently 8. Zygodactyl numbered from inside to outside, so the thumb is ‘toe one’, index-fnger 9. Lobate is ‘toe two’, long-fnger is ‘toe three’ and ring-fnger is ‘toe four’ – the little 10. Heterodactyl fnger is no longer there and has evolved away entirely. 11. Pamprodactyl 12. Didactyl Photography by Ben McNutt by Photography Anisodactyl Tracks ‘Aniso’ - meaning ‘unequal’. ‘Common things occur commonly’. -

Cornell Notes World War II to 1968

The Papers of F. G. Marcham: III Cornell Notes World War II to 1968 By Frederick G. Marcham Edited by John Marcham The Internet-First University Press Ithaca, New York 2006 The Papers of F. G. Marcham: III Cornell Notes World War II to 1968 By Frederick G. Marcham Edited by John Marcham The Internet-First University Press Ithaca, New York 2006 The Internet-First University Press Ithaca NY 14853 Copyright © 2006 by John Marcham Cover: Professor Marcham in his office in McGraw Hall, March 4, 1987, in his 63rd year of teaching at Cornell University. —Charles Harrington, University Photos. For permission to quote or otherwise reproduce from this volume, write John Marcham, 414 E. Buffalo St., Ithaca, N.Y., U.S.A. (607) 273-5754. My successor handling this copyright will be my daughter Sarah Marcham, 131 Upper Creek Rd., Freeville, N.Y. 13068 (607) 347-6633. Printed in the United States of America ii Cornell Notes: World War II to 1968 by Frederick G. Marcham Contents Finding a President ...................................................................1 The Status of Faculty Trustees .................................................2 Dean of the Faculty Battles ......................................................3 Public Office Beckons ..............................................................7 To Be Annexed or Not? ............................................................8 And Now Mayor .....................................................................11 Village and Academe ..............................................................12