The American Museum of Natural History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

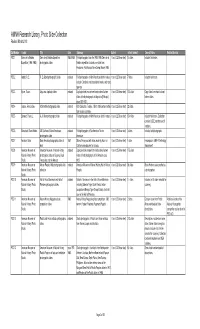

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013 Call Number Creator Title Date Summary Extent Extent (format) General Notes Related Archival PSC 1 Cerro de la Neblina Cerro de la Neblina Expedition 1984-1989 Field photographs from the 1984-1985 Cerro de la 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 14 slides Includes field notes. Expedition (1984-1985) photographic slides Neblina expedition. Includes one slide from Amazonas, Rio Mavaca Base Camp, March 1989. PSC 2 Abbott, R. E. R. E. Abbott photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature, 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 7 slides Includes field notes. includes Cardinals, red-shouldered hawks, and song sparrow. PSC 3 Byron, Oscar. Abyssinia duplicate slides undated Duplicate slides made from hand-colored lantern 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 100 slides Copy slides from hand colored slides of field photographs in Abyssinia [Ethiopia] lantern slides. circa 1920-1921. PSC 4 Jaques, Francis Lee. ACA textile photographic slides undated ACA Collection. Textiles, 15th to 18th century textiles 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 22 slides from various countries. PSC 5 Bierwert, Thane L. A. A. Allen photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature. 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 154 slides Includes field notes. Collection contains USDE numbers and K numbers. PSC 6 Blanchard, Dean Hobbs. AG Southwest Native Americans undated Field photographs of Southwestern Native 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 3 slides Includes field photographs. photographic slides Americans PSC 7 Amadon, Dean Dean Amadon photographic slides of 1957 Slide of fence post with holes made by Acorn or 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 1 slide Fence post in AMNH Ornithology birds California woodpecker for storage. -

A Timeline of Significant Events in the Development of North American Mammalogy

SpecialSpecial PublicationsPublications MuseumMuseum ofof TexasTexas TechTech UniversityUniversity NumberNumber xx66 21 Novemberxx XXXX 20102017 A Timeline of SignificantTitle Events in the Development of North American Mammalogy Molecular Biology Structural Biology Biochemistry Microbiology Genomics Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Computer Science Statistics Physical Chemistry Information Technology Mathematics David J. Schmidly, Robert D. Bradley, Lisa C. Bradley, and Richard D. Stevens Front cover: This figure depicts a chronological presentation of some of the significant events, technological breakthroughs, and iconic personalities in the history of North American mammalogy. Red lines and arrows depict the chronological flow (i.e., top row – read left to right, middle row – read right to left, and third row – read left to right). See text and tables for expanded interpretation of the importance of each person or event. Top row: The first three panels (from left) are associated with the time period entitled “The Emergence Phase (16th‒18th Centuries)” – Mark Catesby’s 1748 map of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, Thomas Jefferson, and Charles Willson Peale; the next two panels represent “The Discovery Phase (19th Century)” – Spencer Fullerton Baird and C. Hart Merriam. Middle row: The first two panels (from right) represent “The Natural History Phase (1901‒1960)” – Joseph Grinnell and E. Raymond Hall; the next three panels (from right) depict “The Theoretical and Technological Phase (1961‒2000)” – illustration of Robert H. MacArthur and Edward O. Wilson’s theory of island biogeography, karyogram depicting g-banded chromosomes, and photograph of electrophoretic mobility of proteins from an allozyme analysis. Bottom row: These four panels (from left) represent the “Big Data Phase (2001‒present)” – chromatogram illustrating a DNA sequence, bioinformatics and computational biology, phylogenetic tree of mammals, and storage banks for a supercomputer. -

Karl Jordan: a Life in Systematics

AN ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION OF Kristin Renee Johnson for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of SciencePresented on July 21, 2003. Title: Karl Jordan: A Life in Systematics Abstract approved: Paul Lawrence Farber Karl Jordan (1861-1959) was an extraordinarily productive entomologist who influenced the development of systematics, entomology, and naturalists' theoretical framework as well as their practice. He has been a figure in existing accounts of the naturalist tradition between 1890 and 1940 that have defended the relative contribution of naturalists to the modem evolutionary synthesis. These accounts, while useful, have primarily examined the natural history of the period in view of how it led to developments in the 193 Os and 40s, removing pre-Synthesis naturalists like Jordan from their research programs, institutional contexts, and disciplinary homes, for the sake of synthesis narratives. This dissertation redresses this picture by examining a naturalist, who, although often cited as important in the synthesis, is more accurately viewed as a man working on the problems of an earlier period. This study examines the specific problems that concerned Jordan, as well as the dynamic institutional, international, theoretical and methodological context of entomology and natural history during his lifetime. It focuses upon how the context in which natural history has been done changed greatly during Jordan's life time, and discusses the role of these changes in both placing naturalists on the defensive among an array of new disciplines and attitudes in science, and providing them with new tools and justifications for doing natural history. One of the primary intents of this study is to demonstrate the many different motives and conditions through which naturalists came to and worked in natural history. -

The 2 Fundamental Questions: Linneaus and Kirchner

2/1/2011 The 2 fundamental questions: y Has evolution taken pp,lace, and if so, what is the Section 4 evidence? Professor Donald McFarlane y If evolution has taken place, what is the mechanism by which it works? Lecture 2 Evolutionary Ideas Evidence for evolution before Darwin Golden Age of Exploration y Magellan’s voyage –1519 y John Ray –University of y Antonius von Leeuwenhoek ‐ microbes –1683 Cambridge (England) y “Catalog of Cambridge Plants” – 1660 –lists 626 species y 1686 –John Ray listing thousands of plant species! y In 1678, Francis Willoughby publishes “Ornithology” Linneaus and Kirchner Athenasius Kircher ~ 1675 –Noah’s ark Carl Linneaus – Sistema Naturae ‐ 1735 Ark too small!! Uses a ‘phenetic” classification – implies a phylogenetic relationship! 300 x 50 x 30 cubits ~ 135 x 20 x 13 m 1 2/1/2011 y Georges Cuvier 1769‐ 1832 y “Fixity of Species” Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 • Enormous diversity of life –WHY ??? JBS Haldane " The Creator, if He exists, has "an inordinate fondness for beetles" ". Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y The discovery of variation. y Comparative Anatomy. Pentadactyl limbs Evidence for Evolution –prior to Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 1830 y Fossils – homologies with living species y Vestigal structures Pentadactyl limbs !! 2 2/1/2011 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 Evidence for Evolution –prior to 1830 y Invariance of the fossil sequence y Plant and animal breeding JBS Haldane: “I will give up my belief in evolution if someone finds a fossil rabbit in the Precambrian.” Charles Darwin Jean Baptiste Lamark y 1744‐1829 y 1809 –1882 y Organisms have the ability to adapt to their y Voyage of Beagle 1831 ‐ 1836 environments over the course of their lives. -

Information Theory, Evolution, and the Origin of Life

Information theory, evolution, and the origin of life HUBERT P. YOCKEY CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS CA\15RIDG£ \J);IVE;<SITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao Paulo, Delhi, Dubai, Tokyo, Mexico City Cambridge University Press 32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473• USA wv1rw.cambridge.org Information on this tide: www.cambridge.org/978opu69585 © Hubert P. Yockey 2005 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2005 Reprinred 2006 First paperback edition 2010 A catalog record for this publication is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication data Yockey, Hubert P. Information theory, evolution, and the origin of life I Huberr P. Yockey. p. em. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) . ISS� 0·521·80293-8 (hardback: alk. paper) r. Molecular biology. 2. Information theory in biology. 3· Evolution (Biology) 4· Life-Origin. r. Title. QHso6.Y634 2004 572.8 dc22 2004054518 ISBN 978-0·)21-80293-2 Hardback ISBN 978-0-52H6958-5 Paperback Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for rhe persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party internet websites referred to in this publication, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Information theory, evolution, and the origin of life Information TheOI)\ Evolution, and the Origin of Life presents a timely introduction to the use of information theory and coding theory in molecular biology. -

Tempo and Mode in Evolution WALTER M

Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 91, pp. 6717-6720, July 1994 Colloquium Paper This paper was presented at a colloquium entiled "Tempo and Mode in Evoluton" organized by Walter M. Fitch and Francisco J. Ayala, held Januwy 27-29, 1994, by the National Academy of Sciences, in Irvine, CA. Tempo and mode in evolution WALTER M. FITCH AND FRANCISCO J. AYALA Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA 92717 George Gaylord Simpson said in his classic Tempo andMode The conflict between Mendelians and biometricians was in Evolution (1) that paleontologists enjoy special advantages resolved between 1918 and 1931 by the work ofR. A. Fisher over geneticists on two evolutionary topics. One general and J. B. S. Haldane in England, Sewall Wright in the United topic, suggested by the word "tempo," has to do with States, and S. S. Chetverikov in Russia. Independently of "evolutionary rates. ., their acceleration and deceleration, each other, these authors proposed theoretical models of the conditions ofexceptionally slow or rapid evolutions, and evolutionary processes which integrate Mendelian inheri- phenomena suggestive of inertia and momentum." A group tance, natural selection, and biometrical knowledge. of related problems, implied by the word "mode," involves The work of these authors, however, had a limited impact "the study of the way, manner, or pattern of evolution, a on the biology of the time, because it was formulated in study in which tempo is a basic factor, but which embraces difficult mathematical language and because it was largely considerably more than tempo" (pp. xvii-xviii). theoretical with little empirical support. -

The Beginnings of Vertebrate Paleontology in North America Author(S): George Gaylord Simpson Source: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol

The Beginnings of Vertebrate Paleontology in North America Author(s): George Gaylord Simpson Source: Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 86, No. 1, Symposium on the Early History of Science and Learning in America (Sep. 25, 1942), pp. 130-188 Published by: American Philosophical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/985085 . Accessed: 29/09/2013 21:55 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Philosophical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 150.135.114.183 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:55:20 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE BEGINNINGS OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY IN NORTH AMERICA GEORGE GAYLORD SIMPSON Associate Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History (Read February14, 1942, in Symposiumon theEarly Historyof Science and Learning in America) CONTENTS siderablevariety of vertebratefossils had been foundin before1846, the accepteddate of that dis- 132 the far West First Glimpses.... ......................... covery. Amongthem were findsby Lewis and Clark in Longueuil,1739, to Croghan,1766 ......... ........ 135 1804-1806,a good mosasaurskeleton from South Dakota, Identifyingthe Vast Mahmot.................... -

LSNY Proceedings 54-57, 1941-1945

Nf\- i\l HARVARD UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OF THE Museum of Comparative Zoology \ - .>v 4 _ ' /I 1941-1945 Nos. 54-57 PROCEEDINGS OF THE . LINNAEAN SOCIETY OF NEW YORK For the Four Years Ending March, 1945 Date of Issue, September 16, 1946 J • r'-' ;; :j 1941-1945 Nos. 54-57 PROCEEDINGS OF THE LINNAEAN SOCIETY OF NEW YORK For the Four Years Ending March, 1945 Date of Issue, September 16, 1946 S^t-, .7- Table of Contents Some Critical Phylogenetic Stages Leading to the Flight of Birds William K. Gregory 1 The Chickadee Flight of 1941-1942 Hustace H. Poor 16 The Ornithological Year 1944 in the New York City Region John L. Bull, Jr. 28 Suggestions to the Field Worker and Bird Bander Avian Pathology 36 Collecting Mallophaga 38 General Notes Rare Gulls at The Narrows, Brooklyn, in the Winter of 1943-1944 40 Comments on Identifying Rare Gulls 42 Breeding of the Herring Gull in Connecticut — 43 Data on Some of the Seabird Colonies of Eastern Long Island 44 New York City Seabird Colonies 46 Royal Terns on Long Island 47 A Feeding Incident of the Black-Billed Cuckoo 49 Eastern Long Island Records of the Nighthawk 50 Proximity of Occupied Kingfisher Nests 51 Further Spread of the Prairie Horned Lark on Long Island 52 A Late Black-Throated Warbler 53 Interchange of Song between Blue-Winged and Golden-Winged Warblers 1942- 53 Predation by Grackles 1943- 54 1944- Observations on Birds Relative to the Predatory New York Weasel 56 Clinton Hart Merriam (1855-1942) First President of the Linnaean Society of New York A. -

George Gaylord Simpson Mammal Tooth Structure Horse Phylogeny Member Profile Book Review Idaho State Fossil

Florida Fossil Horse Newsletter Volume 2 Number 3 3rd Quarter--September 1993 What's Inside? Fossil Skeletons and Mother Lodes George Gaylord Simpson Mammal Tooth Structure Horse Phylogeny Member Profile Book Review Idaho State Fossil Fossil Skeletons and Mother Lodes For those who have collected old bones and teeth from Florida, you can attest to the fact that although fossil mammals are indeed plentiful, they are usually found disarticulated; the skeletons are almost never found in tact. Localities throughout the world that do preserve complete skeletons are indeed rare and these have been called Lagerstätten, a German term roughly meaning "mother lode." Steve Gould once noted that ".Lagerstätten are rare, but their contributions to our knowledge of life's history is disproportionate to their frequency." Why is this so? For invertebrates, soft- bodied organisms may be preserved thus giving insight into various fossil groups not normally fossilized (see Book Review below). For vertebrates the same can be true. At the fabulous Eocene Messel in Germany, carbonized impressions of stomach contents of palaeotheres (close relatives of horses, see chart on page 6) indicate that they were eating grapes, and that bats were eating butterflies. For other Lagerstätten containing vertebrates, the Scientific value is in the completeness of the skeleton. These entire specimens allow paleontologists to decipher the anatomy and biology of these extinct organisms. The western U. S. has several examples of extraordinary localities with complete fossil skeletons that can be considered Lagerstätten. During our trip out west on our way to Salt Lake City, we had the opportunity to visit some of these truly extraordinary fossil sites. -

Biographical Memoirs

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES G EORGE GAYLORD S IMPSON 1902—1984 A Biographical Memoir by E V E R E T T O LSON Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1991 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. GEORGE GAYLORD SIMPSON June 16, 1902-October 6, 1984 BY EVERETT C. OLSON1 EORGE GAYLORD SIMPSON'S passing in 1984 brought Gan era in vertebrate paleontology to an end. Along with Edward Drinker Cope, Henry Fairfield Osborn, and Alfred Sherwood Romer, Simpson ranks among the great paleon- tologists of our time. The intellects of several generations of students were shaped by either following or rejecting his ele- gant analyses and interpretations of evolution and the history of life. Although the "Simpson Era" had its roots in the 1920s and 1930s, it seemed to emerge fully formed and without precedent with the publication of Tempo and Mode in Evolution (delayed until 1944 by World War II), following belatedly on the heels of Quantitative Zoology (1939), which Simpson had written with Anne Roe. Both books left researchers in a va- riety of fields pondering and often revising, conceptual bases 1 Although I had earlier written a memorial to George Gaylord Simpson for the Geological Society of America, I agreed to prepare a more intimate and more per- sonal essay for the National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoirs. The more objective accounts of his life include the essay mentioned above (Memorial Series, Geological Society of America, 1985) and the essay by Bobb Schaeffer and Malcolm McKenna (News Bulletin, Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, no. -

Cornell Notes World War II to 1968

The Papers of F. G. Marcham: III Cornell Notes World War II to 1968 By Frederick G. Marcham Edited by John Marcham The Internet-First University Press Ithaca, New York 2006 The Papers of F. G. Marcham: III Cornell Notes World War II to 1968 By Frederick G. Marcham Edited by John Marcham The Internet-First University Press Ithaca, New York 2006 The Internet-First University Press Ithaca NY 14853 Copyright © 2006 by John Marcham Cover: Professor Marcham in his office in McGraw Hall, March 4, 1987, in his 63rd year of teaching at Cornell University. —Charles Harrington, University Photos. For permission to quote or otherwise reproduce from this volume, write John Marcham, 414 E. Buffalo St., Ithaca, N.Y., U.S.A. (607) 273-5754. My successor handling this copyright will be my daughter Sarah Marcham, 131 Upper Creek Rd., Freeville, N.Y. 13068 (607) 347-6633. Printed in the United States of America ii Cornell Notes: World War II to 1968 by Frederick G. Marcham Contents Finding a President ...................................................................1 The Status of Faculty Trustees .................................................2 Dean of the Faculty Battles ......................................................3 Public Office Beckons ..............................................................7 To Be Annexed or Not? ............................................................8 And Now Mayor .....................................................................11 Village and Academe ..............................................................12 -

Interview with Heinz Lowenstam

HEINZ A. LOWENSTAM (1912-1993) INTERVIEWED BY Heidi Aspaturian June 21-August 2, 1988 ARCHIVES CALIFORNIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Pasadena, California Subject area Geology, geobiology Abstract Interview conducted in eight sessions in the summer of 1988 with Heinz A. Lowenstam, professor of paleoecology. Dr. Lowenstam was born in Germany and educated at the universities of Frankfurt and Munich. He emigrated to the United States in 1937 to continue his graduate studies in geology and paleontology at the University of Chicago, receiving the PhD there in 1939. After a stint at the Illinois State Museum, he joined the Chicago faculty in 1948, working with Harold C. Urey on paleotemperatures. He joined Caltech’s Geology Division in 1952 as a professor of paleoecology, pursuing research in a variety of fields. In 1962, he identified iron in chiton teeth, the first known instance of biomineralization, later found in such diverse creatures as bacteria, honeybees, and birds. In this interview, he recalls the difficulties he faced as a Jew in Nazi Germany, his graduate work in Palestine in the mid-1930s, his life as an émigré, his investigation of Silurian fossils in the Chicago area, and his interaction with such mentors and colleagues at Chicago as Urey, N. L. Bowen, Bailey Willis, Bryan Patterson, and Karl Schmidt. He discusses the evolution of the Geology Division at Caltech; its important move, under division chairman Robert P. Sharp, into geochemistry in the early 1950s; his work on the http://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechOH:OH_Lowenstam_H paleoecology of marine organisms; his recollections of Caltech colleagues, including Sam Epstein, Beno Gutenberg, Hugo Benioff, James Westphal, Max Delbruck, and George Rossman; and the changes that took place in the division over the decades since his arrival.