Leslie Brown and Dean Amadon. Text Figs., 3 Tables. Cloth, Boxed. $59.50

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013 Call Number Creator Title Date Summary Extent Extent (format) General Notes Related Archival PSC 1 Cerro de la Neblina Cerro de la Neblina Expedition 1984-1989 Field photographs from the 1984-1985 Cerro de la 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 14 slides Includes field notes. Expedition (1984-1985) photographic slides Neblina expedition. Includes one slide from Amazonas, Rio Mavaca Base Camp, March 1989. PSC 2 Abbott, R. E. R. E. Abbott photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature, 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 7 slides Includes field notes. includes Cardinals, red-shouldered hawks, and song sparrow. PSC 3 Byron, Oscar. Abyssinia duplicate slides undated Duplicate slides made from hand-colored lantern 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 100 slides Copy slides from hand colored slides of field photographs in Abyssinia [Ethiopia] lantern slides. circa 1920-1921. PSC 4 Jaques, Francis Lee. ACA textile photographic slides undated ACA Collection. Textiles, 15th to 18th century textiles 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 22 slides from various countries. PSC 5 Bierwert, Thane L. A. A. Allen photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature. 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 154 slides Includes field notes. Collection contains USDE numbers and K numbers. PSC 6 Blanchard, Dean Hobbs. AG Southwest Native Americans undated Field photographs of Southwestern Native 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 3 slides Includes field photographs. photographic slides Americans PSC 7 Amadon, Dean Dean Amadon photographic slides of 1957 Slide of fence post with holes made by Acorn or 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 1 slide Fence post in AMNH Ornithology birds California woodpecker for storage. -

Melagiris (Tamil Nadu)

MELAGIRIS (TAMIL NADU) PROPOSAL FOR IMPORTANT BIRD AREA (IBA) State : Tamil Nadu, India District : Krishnagiri, Dharmapuri Coordinates : 12°18©54"N 77°41©42"E Ownership : State Area : 98926.175 ha Altitude : 300-1395 m Rainfall : 620-1000 mm Temperature : 10°C - 35°C Biographic Zone : Deccan Peninsula Habitats : Tropical Dry Deciduous, Riverine Vegetation, Tropical Dry Evergreen Proposed Criteria A1 (Globally Threatened Species) A2 (Endemic Bird Area 123 - Western Ghats, Secondary Area s072 - Southern Deccan Plateau) A3 (Biome-10 - Indian Peninsula Tropical Moist Forest, Biome-11 - Indo-Malayan Tropical Dry Zone) GENERAL DESCRIPTION The Melagiris are a group of hills lying nestled between the Cauvery and Chinnar rivers, to the south-east of Hosur taluk in Tamil Nadu, India. The Melagiris form part of an almost unbroken stretch of forests connecting Bannerghatta National Park (which forms its north-western boundary) to the forests of Cauvery Wildlife Sanctuary - Karnataka (which forms its southern boundary, separated by the river Cauvery), and further to Biligirirangan hills and Sathyamangalam forests. The northern and western parts are comparatively plain and is part of the Mysore plateau. The average elevation in this region is 500-1000 m. Ground sinks to 300m in the valley of the Cauvery and the highest point is the peak of Guthereyan at 1395.11 m. Red sandy loam is the most common soil type found in this region. Small deposits of alluvium are found along Cauvery and Chinnar rivers and Kaoline is found in some areas near Jowlagiri. The temperature ranges from 10°C ± 35°C. South-west monsoon is fairly active mostly in the northern areas, but north-east monsoon is distinctly more effective in the region. -

White-Throated Nightjar Eurostopodus Mystacalis: Diurnal Over-Sea Migration in a Nocturnal Bird

32 AUSTRALIAN FIELD ORNITHOLOGY 2011, 28, 32–37 White-throated Nightjar Eurostopodus mystacalis: Diurnal Over-sea Migration in a Nocturnal Bird MIKE CARTER1 and BEN BRIGHT2 130 Canadian Bay Road, Mount Eliza, Victoria 3930 (Email: [email protected]) 2P.O. Box 643, Weipa, Queensland 4874 Summary A White-throated Nightjar Eurostopodus mystacalis was photographed flying low above the sea in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Queensland, at ~1600 h on 25 August 2010. Sightings of Nightjars behaving similarly in the same area in the days before obtaining the conclusive photographs suggest that they were on southerly migration, returning from their wintering sojourn in New Guinea to their breeding grounds in Australia. Other relevant sightings are given, and the significance of this behaviour is discussed. The evidence Observations in 2010 At 0900 h on 21 August 2010, whilst conducting a fishing charter by boat in the Gulf of Carpentaria off the western coast of Cape York, Queensland, BB observed an unusual bird flying low over the sea. Although his view was sufficient to excite curiosity, it did not enable identification. Twice on 23 August 2010, the skipper of a companion vessel, who had been alerted to the sighting, had similar experiences. Then at 1600 h on 25 August 2010, BB saw ‘the bird’ again. In order to determine its identity, he followed it, which necessitated his boat reaching speeds of 20–25 knots. During the pursuit, which lasted 10–15 minutes, he obtained over 15 photographs and a video recording. He formed the opinion that the bird was a nightjar, most probably a White-throated Nightjar Eurostopodus mystacalis. -

Bird Diversity of Protected Areas in the Munnar Hills, Kerala, India

PRAVEEN & NAMEER: Munnar Hills, Kerala 1 Bird diversity of protected areas in the Munnar Hills, Kerala, India Praveen J. & Nameer P. O. Praveen J., & Nameer P.O., 2015. Bird diversity of protected areas in the Munnar Hills, Kerala, India. Indian BIRDS 10 (1): 1–12. Praveen J., B303, Shriram Spurthi, ITPL Main Road, Brookefields, Bengaluru 560037, Karnataka, India. Email: [email protected] Nameer P. O., Centre for Wildlife Studies, College of Forestry, Kerala Agricultural University, KAU (PO), Thrissur 680656, Kerala, India. India. [email protected] Introduction Table 1. Protected Areas (PA) of Munnar Hills The Western Ghats, one of the biodiversity hotspots of the Protected Area Abbreviation Area Year of world, is a 1,600 km long chain of mountain ranges running (in sq.km.) formation parallel to the western coast of the Indian peninsula. The region Anamudi Shola NP ASNP 7.5 2003 is rich in endemic fauna, including birds, and has been of great biogeographical interest. Birds have been monitored regularly Eravikulam NP ENP 97 1975 in the Western Ghats of Kerala since 1991, with more than 60 Kurinjimala WLS KWLS 32 2006 surveys having been carried out in the entire region (Praveen & Pampadum Shola NP PSNP 11.753 2003 Nameer 2009). This paper is a result of such a survey conducted in December 2012 supplemented by relevant prior work in this area. Anamalais sub-cluster in southern Western Ghats (Nair 1991; Das Munnar Hills (10.083°–10.333°N, 77.000°–77.617°E), et al. 2006). Anamudi (2685 m), the highest peak in peninsular forming part of the High Ranges of Western Ghats, also known as India, lies in these hills inside Eravikulam National Park (NP). -

Western India Tour Report 2019

We had great views of the critically endangered Great Indian Bustard in Desert National Park (Frédéric Pelsy). WESTERN INDIA 23 JANUARY – 8 FEBRUARY 2019 LEADER: HANNU JÄNNES Another very successful Birdquest tour to western of India traced an epic route through the states of Punjab, Rajasthan and Gujarat, with a short visit to the state of Maharasthra to conclude. We recorded no fewer than 326 bird species and 20 mammals, and, more importantly, we found almost every bird specialty of the dry western and central regions of the subcontinent including a number of increasingly scarce species with highly restricted ranges. Foremost of these were the impressive Great Indian Bustard (with a world population of less than 100 individuals), the stunningly patterned White-naped Tit, White-browed (or Stoliczka’s) Bush Chat and the Critically Endangered Indian Vulture. Many Indian subcontinent endemics were seen with Rock Bush Quail, Red Spurfowl, Red-naped (or Black) Ibis, Indian Courser, Painted Sandgrouse, the very localized Forest Owlet, Mottled Wood Owl and Indian Eagle-Owl, White-naped Woodpecker, Plum-headed and Malabar Parakeets, Bengal Bush, Rufous-tailed and Sykes’s Larks, Ashy- crowned Sparrow-Lark, the lovely White-bellied Minivet, Marshall’s Iora, Indian Black-lored Tit, Brahminy 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Western India www.birdquest-tours.com Starling, Rufous-fronted Prinia, Rufous-vented Grass-Babbler, Green Avadavat, Indian Scimitar Babbler, Indian Spotted Creeper, Vigors’s Sunbird, Sind Sparrow and the range restricted western form -

![Explorer Research Article [Tripathi Et Al., 6(3): March, 2015:4304-4316] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES (Int](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4638/explorer-research-article-tripathi-et-al-6-3-march-2015-4304-4316-coden-usa-ijplcp-issn-0976-7126-international-journal-of-pharmacy-life-sciences-int-1074638.webp)

Explorer Research Article [Tripathi Et Al., 6(3): March, 2015:4304-4316] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL of PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES (Int

Explorer Research Article [Tripathi et al., 6(3): March, 2015:4304-4316] CODEN (USA): IJPLCP ISSN: 0976-7126 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PHARMACY & LIFE SCIENCES (Int. J. of Pharm. Life Sci.) Study on Bird Diversity of Chuhiya Forest, District Rewa, Madhya Pradesh, India Praneeta Tripathi1*, Amit Tiwari2, Shivesh Pratap Singh1 and Shirish Agnihotri3 1, Department of Zoology, Govt. P.G. College, Satna, (MP) - India 2, Department of Zoology, Govt. T.R.S. College, Rewa, (MP) - India 3, Research Officer, Fishermen Welfare and Fisheries Development Department, Bhopal, (MP) - India Abstract One hundred and twenty two species of birds belonging to 19 orders, 53 families and 101 genera were recorded at Chuhiya Forest, Rewa, Madhya Pradesh, India from all the three seasons. Out of these as per IUCN red list status 1 species is Critically Endangered, 3 each are Vulnerable and Near Threatened and rest are under Least concern category. Bird species, Gyps bengalensis, which is comes under Falconiformes order and Accipitridae family are critically endangered. The study area provide diverse habitat in the form of dense forest and agricultural land. Rose- ringed Parakeets, Alexandrine Parakeets, Common Babblers, Common Myna, Jungle Myna, Baya Weavers, House Sparrows, Paddyfield Pipit, White-throated Munia, White-bellied Drongo, House crows, Philippine Crows, Paddyfield Warbler etc. were prominent bird species of the study area, which are adapted to diversified habitat of Chuhiya Forest. Human impacts such as Installation of industrial units, cutting of trees, use of insecticides in agricultural practices are major threats to bird communities. Key-Words: Bird, Chuhiya Forest, IUCN, Endangered Introduction Birds (class-Aves) are feathered, winged, two-legged, Birds are ideal bio-indicators and useful models for warm-blooded, egg-laying vertebrates. -

SOUTHERN INDIA and SRI LANKA

Sri Lanka Woodpigeon (all photos by D.Farrow unless otherwise stated) SOUTHERN INDIA and SRI LANKA (WITH ANDAMANS ISLANDS EXTENSION) 25 OCTOBER – 19 NOVEMBER 2016 LEADER: DAVE FARROW This years’ tour to Southern India and Sri Lanka was once again a very successful and enjoyable affair. A wonderful suite of endemics were seen, beginning with our extension to the Andaman Islands where we were able to find 20 of the 21 endemics, with Andaman Scops and Walden’s Scops Owls, Andaman and Hume’s Hawk Owls leading the way, Andaman Woodpigeon and Andaman Cuckoo Dove, good looks at 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: South India and Sri Lanka 2016 www.birdquest-tours.com Andaman Crake, plus all the others with the title ‘Andaman’ (with the exception of the Barn Owl) and a rich suite of other birds such as Ruddy Kingfisher, Oriental Pratincole, Long-toed Stint, Long-tailed Parakeets and Mangrove Whistler. In Southern India we birded our way from the Nilgiri Hills to the lowland forest of Kerala finding Painted and Jungle Bush Quail, Jungle Nightjar, White-naped and Heart-spotted Woodpeckers, Malabar Flameback, Malabar Trogons, Malabar Barbet, Blue-winged Parakeet, Grey-fronted Green Pigeons, Nilgiri Woodpigeon, Indian Pitta (with ten seen on the tour overall), Jerdon's Bushlarks, Malabar Larks, Malabar Woodshrike and Malabar Whistling Thrush, Black-headed Cuckooshrike, Black-and- Orange, Nilgiri, Brown-breasted and Rusty-tailed Flycatchers, Nilgiri and White-bellied Blue Robin, Black- chinned and Kerala Laughingthrushes, Dark-fronted Babblers, Indian Rufous Babblers, Western Crowned Warbler, Indian Yellow Tit, Indian Blackbird, Hill Swallow, Nilgiri Pipit, White-bellied Minivet, the scarce Yellow-throated and Grey-headed Bulbuls, Flame-throated and Yellow-browed Bulbuls, Nilgiri Flowerpecker, Loten's Sunbird, Black-throated Munias and the stunning endemic White-bellied Treepie. -

Kanha Survey Bird ID Guide (Pdf; 11

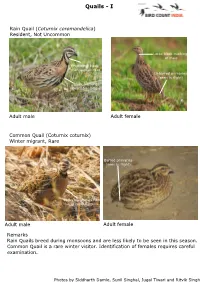

Quails - I Rain Quail (Coturnix coromandelica) Resident, Not Uncommon Lacks black markings of male Prominent black markings on face Unbarred primaries (seen in flight) Black markings (variable) below Adult male Adult female Common Quail (Coturnix coturnix) Winter migrant, Rare Barred primaries (seen in flight) Lacks black markings of male Rain Adult male Adult female Remarks Rain Quails breed during monsoons and are less likely to be seen in this season. Common Quail is a rare winter visitor. Identification of females requires careful examination. Photos by Siddharth Damle, Sunil Singhal, Jugal Tiwari and Ritvik Singh Quails - II Jungle Bush-Quail (Perdicula asiatica) Resident, Common Rufous and white supercilium Rufous & white Brown ear-coverts supercilium and Strongly marked brown ear-coverts above Rock Bush-Quail (Perdicula argoondah) Resident, Not Uncommon Plain head without Lacks brown ear-coverts markings Little or no streaks and spots above Remarks Jungle is typically more common than Rock in Central India. Photos by Nikhil Devasar, Aseem Kumar Kothiala, Siddharth Damle and Savithri Singh Crested (Oriental) Honey Buzzard (Pernis ptilorhynchus) Resident, Common Adult plumages: male (left), female (right) 'Pigeon-headed', weak bill Weak bill Long neck Long, slender Variable streaks and and weak markings below build Adults in flight: dark morph male (left), female (right) Confusable with Less broad, rectangular Crested Hawk-Eagle wings Rectangular wings, Confusable with Crested Serpent not broad Eagle Long neck Juvenile plumages Confusable -

Palau Bird Survey Report 2020

Abundance of Birds in Palau based on Surveys in 2005 Final Report, November 2020 Eric A. VanderWerf1 and Erika Dittmar1 1 Pacific Rim Conservation, 3038 Oahu Avenue, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Prepared for the Belau National Museum, Box 666, Koror Palau 96940 Endemic birds of Palau, from top left: White-breasted Woodswallow, Palau Fantail, Palau Fruit- dove, Rusty-capped Kingfisher. Photos by Eric VanderWerf. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .............................................................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 5 METHODS ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Description of Study Area and Transect Locations ............................................................ 6 Data Collection ................................................................................................................... 7 Data Analysis ...................................................................................................................... 7 Limitations of the Survey.................................................................................................... 9 RESULTS .................................................................................................................................... -

Emergency Plan

Environmental Impact Assessment Project Number: 43253-026 November 2019 India: Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Investment Program – Project 2 Vijayanagara Channels Annexure 5–9 Prepared by Project Management Unit, Karnataka Integrated and Sustainable Water Resources Management Investment Program Karnataka Neeravari Nigam Ltd. for the Asian Development Bank. This is an updated version of the draft originally posted in June 2019 available on https://www.adb.org/projects/documents/ind-43253-026-eia-0 This environmental impact assessment is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Annexure 5 Implementation Plan PROGRAMME CHART FOR CANAL LINING, STRUCTURES & BUILDING WORKS Name Of the project:Modernization of Vijaya Nagara channel and distributaries Nov-18 Dec-18 Jan-19 Feb-19 Mar-19 Apr-19 May-19 Jun-19 Jul-19 Aug-19 Sep-19 Oct-19 Nov-19 Dec-19 Jan-20 Feb-20 Mar-20 Apr-20 May-20 Jun-20 Jul-20 Aug-20 Sep-20 Oct-20 Nov-20 Dec-20 S. No Name of the Channel 121212121212121212121212121212121212121212121212121 2 PACKAGE -

The American Museum of Natural History

THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT JULY, 1953, THROUGH JUNE, 1954 THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT JULY, 1953, THROUGH JUNE, 1954 THE CITY OF NEW YORK 1954 EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT To the Trustees of The American Museum of Natural History and to the Municipal Authorities of the City of New York THE Museum's fiscal year, which ended June 30, 1954, was a good one. As in our previous annual report, I believe we can fairly state that continuing progress is being made on our long-range plan for the Museum. The cooperative attitude of the scientific staff and of our other employees towards the program set forth by management has been largely responsible for what has been accomplished. The record of both the Endowment and Pension Funds during the past twelve months has been notably satisfactory. In a year of wide swings of optimism and pessimism in the security markets, the Finance Committee is pleased to report an increase in the market value of the Endowment Fund of $3,011,800 (87 per cent of which has been due to the over-all rise in prices and 13 per cent to new gifts). Common stocks held by the fund increased in value approximately 30 per cent in the year. The Pension Fund likewise continued to grow, reaching a valuation of $4,498,600, as compared to $4,024,100 at the end of the previous year. Yield at cost for the Endow- ment Fund as of July 1 stood at 4.97 per cent and for the Pension Fund at 3.74 per cent. -

LSNY Proceedings 54-57, 1941-1945

Nf\- i\l HARVARD UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OF THE Museum of Comparative Zoology \ - .>v 4 _ ' /I 1941-1945 Nos. 54-57 PROCEEDINGS OF THE . LINNAEAN SOCIETY OF NEW YORK For the Four Years Ending March, 1945 Date of Issue, September 16, 1946 J • r'-' ;; :j 1941-1945 Nos. 54-57 PROCEEDINGS OF THE LINNAEAN SOCIETY OF NEW YORK For the Four Years Ending March, 1945 Date of Issue, September 16, 1946 S^t-, .7- Table of Contents Some Critical Phylogenetic Stages Leading to the Flight of Birds William K. Gregory 1 The Chickadee Flight of 1941-1942 Hustace H. Poor 16 The Ornithological Year 1944 in the New York City Region John L. Bull, Jr. 28 Suggestions to the Field Worker and Bird Bander Avian Pathology 36 Collecting Mallophaga 38 General Notes Rare Gulls at The Narrows, Brooklyn, in the Winter of 1943-1944 40 Comments on Identifying Rare Gulls 42 Breeding of the Herring Gull in Connecticut — 43 Data on Some of the Seabird Colonies of Eastern Long Island 44 New York City Seabird Colonies 46 Royal Terns on Long Island 47 A Feeding Incident of the Black-Billed Cuckoo 49 Eastern Long Island Records of the Nighthawk 50 Proximity of Occupied Kingfisher Nests 51 Further Spread of the Prairie Horned Lark on Long Island 52 A Late Black-Throated Warbler 53 Interchange of Song between Blue-Winged and Golden-Winged Warblers 1942- 53 Predation by Grackles 1943- 54 1944- Observations on Birds Relative to the Predatory New York Weasel 56 Clinton Hart Merriam (1855-1942) First President of the Linnaean Society of New York A.