Ernst Mayr and the “Biology of Birds”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

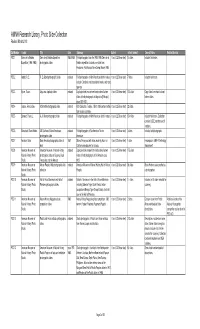

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013

AMNH Research Library, Photo Slide Collection Revised March 2013 Call Number Creator Title Date Summary Extent Extent (format) General Notes Related Archival PSC 1 Cerro de la Neblina Cerro de la Neblina Expedition 1984-1989 Field photographs from the 1984-1985 Cerro de la 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 14 slides Includes field notes. Expedition (1984-1985) photographic slides Neblina expedition. Includes one slide from Amazonas, Rio Mavaca Base Camp, March 1989. PSC 2 Abbott, R. E. R. E. Abbott photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature, 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 7 slides Includes field notes. includes Cardinals, red-shouldered hawks, and song sparrow. PSC 3 Byron, Oscar. Abyssinia duplicate slides undated Duplicate slides made from hand-colored lantern 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 100 slides Copy slides from hand colored slides of field photographs in Abyssinia [Ethiopia] lantern slides. circa 1920-1921. PSC 4 Jaques, Francis Lee. ACA textile photographic slides undated ACA Collection. Textiles, 15th to 18th century textiles 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 22 slides from various countries. PSC 5 Bierwert, Thane L. A. A. Allen photographic slides undated Field photographs of North American birds in nature. 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 154 slides Includes field notes. Collection contains USDE numbers and K numbers. PSC 6 Blanchard, Dean Hobbs. AG Southwest Native Americans undated Field photographs of Southwestern Native 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 3 slides Includes field photographs. photographic slides Americans PSC 7 Amadon, Dean Dean Amadon photographic slides of 1957 Slide of fence post with holes made by Acorn or 1 box (0.25 linear feet) 1 slide Fence post in AMNH Ornithology birds California woodpecker for storage. -

Open Kutz Thesis Final.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY INVESTIGATING THE LARVAL COMPETITIVE ABILITIES OF DIFFERENT CHROMOSOMAL INVERSION PATTERNS WITHIN DROSOPHILA PSEUDOOBSCURA DAVID KUTZ SPRING 2018 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Biology and Spanish, with honors in Biology Reviewed and approved* by the following: Stephen Schaeffer Professor of Biology Thesis Supervisor Michael Axtell Professor of Biology Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT Within the fruit fly species D. pseudoobscura, the third chromosome has a wealth of genetic inversion mutations. These inversions vary in frequency among populations forming geographic clines or gradients under what appears to be strong natural selection. Models of selection – migration balance have suggested that the larval stage of development may be targeted by selection, however, the abiotic or biotic forces behind this selection remain unclear. To test for the influence of temperature and limited resources on selection, we performed larval competition experiments between wild type inversion strains and a standard mutant tester strain to test for differences among six different inversion lines. Our results indicate that when competition is less intense, temperature makes no difference in the ability of different inversion strains to compete. However, when competition is increased, a statistically significant difference in larval competitive success exists among flies -

The Elaborate Postural Display of Courting Drosophila Persimilis Flies Produces Substrate-Borne Vibratory Signals

J Insect Behav DOI 10.1007/s10905-016-9579-8 The Elaborate Postural Display of Courting Drosophila persimilis Flies Produces Substrate-Borne Vibratory Signals Mónica Vega Hernández1 & Caroline Cecile Gabrielle Fabre1 Revised: 9 August 2016 /Accepted: 15 August 2016 # The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Sexual selection has led to the evolution of extraordinary and elaborate male courtship behaviors across taxa, including mammals and birds, as well as some species of flies. Drosophila persimilis flies perform complex courtship behaviors found in most Drosophila species, which consist of visual, air-borne, gustatory and olfactory cues. In addition, Drosophila persimilis courting males also perform an elaborate postural display that is not found in most other Drosophila species. This postural display includes an upwards contortion of their abdomen, specialized movements of the head and forelegs, raising both wings into a Bwing-posture^ and, most remarkably, the males proffer the female a regurgitat- ed droplet. Here, we use high-resolution imaging, laser vibrometry and air-borne acoustic recordings to analyse this postural display to ask which signals may promote copulation. Surprisingly, we find that no air-borne signals are generated during the display. We show, however, that the abdomen tremulates to generate substrate-borne vibratory signals, which correlate with the female’s immobility before she feeds onto the droplet and accepts copulation. Keywords Biotremology.drosophila.persimilis.pseudoobscura.courtship.behavior. abdomen.tremulation.substrate-bornevibrations.femalestationary.quivering.feeding. copulation Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10905-016-9579-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. -

Epilogue: Pattern Cladistics from Goethe to Brady

Epilogue: Pattern Cladistics From Goethe to Brady Most, if not all, ideas in science are recycled, rediscovered, or rehashed, either sur- reptitiously, through rereading and rediscovering old works, or simply (commonly?) through lack of knowledge of past achievements. The idea of transformation—that things might change, transform, convert into other things—for instance, has been proposed many times, by both evolutionists and non-evolutionists alike. Yet the notion of transformation is really a myth, a story which many scientists embrace, a story that tells of living things transforming into other living things, with their role to interpret its meaning and mechanism: The fall of Paradise to the untamed wild, the tamed landscape to the Biblical flood, the reigns of monarchs, a kingdom to a republic and the pastoral to the industrial—of transformations there are plenty. A deep desire to uncover what mechanism(s) lie behind these transformations has provided many explanations, from the acquisition of sin after the fall from grace, to God’s will, to progress, however construed. The belief that every transformation neatly fits a law or model by which nature abides has shaped our way of thinking. Yet concomitant with such thoughts is the recognition that Nature is complex, and that Nature’s complexity obeys no single law or theory that places it neatly into a box. For every law and theory, we are told, there are exceptions, which are given ad hoc explanations. Man may have toiled the soil to shape nature into his or her image of Eden, but complexity does not fit any man-made law. -

Genetics of a Difference in Cuticular Hydrocarbons Between Drosophila Pseudoobscura and D

Genet. Res., Camb. (1996), 68, pp. 117-123 With 3 text-figures Copyright © 1996 Cambridge University Press 117 Genetics of a difference in cuticular hydrocarbons between Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. persimilis MOHAMED A. F. NOOR* AND JERRY A. COYNE Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, Chicago, 1101 E. 57th Street, IL 60637, USA Summary We identify a fixed species difference in the relative Oyama, 1995). Indeed, in almost every insect species concentrations of the cuticular hydrocarbons 2-methyl studied, some cuticular hydrocarbons have been found hexacosane and 5,9-pentacosadiene in Drosophila to play a pheromonal role (Cobb & Ferveur, 1996). pseudoobscura and D. persimilis, and determine its Because these compounds are easily extracted and genetic basis. In backcross males, this difference is due quantified by gas chromatography, they are ideal for to genes on both the X and second chromosomes, genetic studies of reproductive isolation. Three prev- while the other two major chromosomes have no ious studies have found that hydrocarbon differences effect. In backcross females, only the second chromo- between closely related species were probably caused some has a significant effect on hydrocarbon pheno- by only one or a few loci (Grula & Taylor, 1979; type, but dominant genes on the X chromosome could Roelofs et al., 1987; Coyne et al., 1994). also be involved. These results differ in two respects Here we identify a difference in the predominant from previous studies of Drosophila cuticular hydro- cuticular hydrocarbons of the well-known sibling carbons: strong epistasis is observed between the species Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. persimilis, chromosomes that produce the hydrocarbon analyze its genetic basis, and evaluate its potential difference in males, and the difference is apparently effects on reproductive isolation. -

THEODOSIUS DOBZHANSKY January 25, 1900-December 18, 1975

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES T H E O D O S I U S D O B ZHANSKY 1900—1975 A Biographical Memoir by F R A N C I S C O J . A Y A L A Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1985 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. THEODOSIUS DOBZHANSKY January 25, 1900-December 18, 1975 BY FRANCISCO J. AYALA HEODOSIUS DOBZHANSKY was born on January 25, 1900 Tin Nemirov, a small town 200 kilometers southeast of Kiev in the Ukraine. He was the only child of Sophia Voinarsky and Grigory Dobrzhansky (precise transliteration of the Russian family name includes the letter "r"), a teacher of high school mathematics. In 1910 the family moved to the outskirts of Kiev, where Dobzhansky lived through the tumultuous years of World War I and the Bolshevik revolu- tion. These were years when the family was at times beset by various privations, including hunger. In his unpublished autobiographical Reminiscences for the Oral History Project of Columbia University, Dobzhansky states that his decision to become a biologist was made around 1912. Through his early high school (Gymnasium) years, Dobzhansky became an avid butterfly collector. A schoolteacher gave him access to a microscope that Dob- zhansky used, particularly during the long winter months. In the winter of 1915—1916, he met Victor Luchnik, a twenty- five-year-old college dropout, who was a dedicated entomol- ogist specializing in Coccinellidae beetles. -

The American Museum of Natural History

THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT JULY, 1953, THROUGH JUNE, 1954 THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT JULY, 1953, THROUGH JUNE, 1954 THE CITY OF NEW YORK 1954 EIGHTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT To the Trustees of The American Museum of Natural History and to the Municipal Authorities of the City of New York THE Museum's fiscal year, which ended June 30, 1954, was a good one. As in our previous annual report, I believe we can fairly state that continuing progress is being made on our long-range plan for the Museum. The cooperative attitude of the scientific staff and of our other employees towards the program set forth by management has been largely responsible for what has been accomplished. The record of both the Endowment and Pension Funds during the past twelve months has been notably satisfactory. In a year of wide swings of optimism and pessimism in the security markets, the Finance Committee is pleased to report an increase in the market value of the Endowment Fund of $3,011,800 (87 per cent of which has been due to the over-all rise in prices and 13 per cent to new gifts). Common stocks held by the fund increased in value approximately 30 per cent in the year. The Pension Fund likewise continued to grow, reaching a valuation of $4,498,600, as compared to $4,024,100 at the end of the previous year. Yield at cost for the Endow- ment Fund as of July 1 stood at 4.97 per cent and for the Pension Fund at 3.74 per cent. -

LSNY Proceedings 54-57, 1941-1945

Nf\- i\l HARVARD UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OF THE Museum of Comparative Zoology \ - .>v 4 _ ' /I 1941-1945 Nos. 54-57 PROCEEDINGS OF THE . LINNAEAN SOCIETY OF NEW YORK For the Four Years Ending March, 1945 Date of Issue, September 16, 1946 J • r'-' ;; :j 1941-1945 Nos. 54-57 PROCEEDINGS OF THE LINNAEAN SOCIETY OF NEW YORK For the Four Years Ending March, 1945 Date of Issue, September 16, 1946 S^t-, .7- Table of Contents Some Critical Phylogenetic Stages Leading to the Flight of Birds William K. Gregory 1 The Chickadee Flight of 1941-1942 Hustace H. Poor 16 The Ornithological Year 1944 in the New York City Region John L. Bull, Jr. 28 Suggestions to the Field Worker and Bird Bander Avian Pathology 36 Collecting Mallophaga 38 General Notes Rare Gulls at The Narrows, Brooklyn, in the Winter of 1943-1944 40 Comments on Identifying Rare Gulls 42 Breeding of the Herring Gull in Connecticut — 43 Data on Some of the Seabird Colonies of Eastern Long Island 44 New York City Seabird Colonies 46 Royal Terns on Long Island 47 A Feeding Incident of the Black-Billed Cuckoo 49 Eastern Long Island Records of the Nighthawk 50 Proximity of Occupied Kingfisher Nests 51 Further Spread of the Prairie Horned Lark on Long Island 52 A Late Black-Throated Warbler 53 Interchange of Song between Blue-Winged and Golden-Winged Warblers 1942- 53 Predation by Grackles 1943- 54 1944- Observations on Birds Relative to the Predatory New York Weasel 56 Clinton Hart Merriam (1855-1942) First President of the Linnaean Society of New York A. -

The Evolution of Prezygotic Reproductive Isolation in The

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The evolution of prezygotic reproductive isolation in the Drosophila pseudoobscura subgroup Sheri Dixon Schully Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Schully, Sheri Dixon, "The ve olution of prezygotic reproductive isolation in the Drosophila pseudoobscura subgroup" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1001. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1001 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE EVOLUTION OF PREZYGOTIC REPRODUCTIVE ISOLATION IN THE DROSOPHILA PSEUDOOBSCURA SUBGROUP A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Sheri Dixon Schully B.S., Louisiana State University, 2001 August 2005 DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my parents, Lydia and Dale Dixon. My dad taught me the values of first-rate hard work. My mother has always made me feel that I could accomplish anything I put my mind and heart into. It has been her belief in me that has gotten me this far. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to recognize and thank the people who made all of this work possible. First and foremost, I would like to express extreme gratitude to Mike Hellberg for his support and guidance. -

Witmer Stone

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY Vor.. 58 Jut.y, 1941 No. 3 IN MEMORIAM: WITMER STONE BY JAMES A. G. REHN Plate to I• TI•E eminently fitting words of a long-time colleague,"Witmet Stone was born a naturalist, nurtured a naturalist and a naturalist he lived until the end of his days. Most of the many activitiesthat filled his busylife flowedfrom his profoundinterest in nature." Scientist, man of letters,biographer of scienceand scientists,and protectoro• wildlife, he combined with these attainments what another old •riend, Dr. CorneliusWeygandt, has most aptly called "a geniusfor friend- ship." To a buoyant spirit he addedan enthusiasmwhich he kept throughlife, a keensense of humor, a touchof whimsey,a sympathetic understanding,a love of good literature and the instinctsof the his- torian and bibliophile, attributesall of which broadenedhis outlook upon the world and drew him closelyto his fellow men. In his death on May 23, 1939, the American Ornithologists'Union lost an honored Fellow and a former President and Editor, and his associates at the Academyof Natural Scienceswere deprivedof a counselorand coad- jutor who for over fifty yearshad lived as one o• them. Witmet Stonewas born in Philadelphia,September 22, 1866, the second son of Frederick D. and Anne E. Witmet Stone. His ances- try was PennsylvaniaEnglish-Quaker and PennsylvaniaDutch, two stockswhich have given us a number of our famousAmerican natural- ists,such as Melsheimer, Haldeman, Say, von Schweinitz,Darlington, Cassin,Leidy and Cope. His father was for many yearsLibrarian of the Historical Societyof Pennsylvaniaand a recognizedauthority on Pennsylvaniahistory. Doubtlesswe can trace much of Witmet Stone's appreciationof good literature, scholarlywriting and regard for booksand book-makingto an early paternal influence. -

Experience« of Nature: from Salomon Müller to Ernst Mayr, Or the Lnsights of Travelling Naturalists Toward a Zoological Geography and Evolutionary Biology*

Die Entstehung biologischer Disziplinen II -Beiträge zur 10. Jahrestagung der DGGTB The »Experience« of Nature: From Salomon Müller to Ernst Mayr, Or The lnsights of Travelling Naturalists Toward a Zoological Geography and Evolutionary Biology* Matthias GLAUBRECHT (Berlin) Zusammenfassung Wir beurteilen die Theorien und Beiträge früherer Autoren auf der Grundlage ihrer Relevanz für den heutigen Erkenntnisgewinn. Mit Blick auf die oftmals unzureichende Klärung der präzisen geographi schen Herkunft von Materialproben bei nicht wenigen molekulargenetisch-phylogeographischen Studi en (die an aktuellen Arbeiten demonstriert wird), soll die Bedeutung der geographischen »Erfahrung« (im doppelten Wortsinn) - am Beispiel der Erforschung des australasiatischen Raumes - untersucht werden. Anfangs dominierten von staatlicher Seite initiierte bzw. finanzierte Forschungsreisen. Dazu zählen im Gefolge von James CooKS Fahrten durch den Indo-Pazifik beispielsweise die im frühen 19. Jahrhun dert von Naturforschern wie QUOY, ÜAIMARD, LESSON, HUMBRON und JACQUINOT begleiteten franzö• sischen Expeditionen der L 'Uranie, La Coquille und L 'Astrolabe sowie die britischen Expeditionen der Beagle oder der Rattlesnake mit Naturforschern wie DARWIN oder MACGILLIVRAY und HUXLEY. Dazu zählt auch die holländische Expedition der Triton, an der der aus Deutschland stammende Naturforscher Salomon MOLLER (1804-1864) teilnahm, der Jahrzehnte vor Alfred Russe! WALLACE (1823-1913) scharfe Faunendifferenzen im indomalayischen Archipel erkannte und beschrieb. Während diese Forschungsfahrten vorwiegend strategisch-militärische bzw. merkantile Ziele ver folgten, wurde die naturkundliche Erforschung im späteren 19. und beginnenden 20. Jahrhundert insbeson dere von allein reisenden »naturalists« betrieben, wie etwa von W ALLACE, Otto FINSCH (1839-1917) und Richard SEM ON ( 1859-1918), der sich später Expeditionen wie beispielsweise von Erwin STRESEMANN (1889-1972), Bernhard RENSCH (1900-1990) und Ernst MAYR (geb. -

Short History of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia

Short History of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia By Edward J^.mes Nolan UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES A HORT HISTORY y of Natural Sciences PHILADELPHIA EDWARD J. NOLAN, M.D, Recording Secretary and Librarian PHILADELPHIA THE ACADEMY OF NATURAL Sci, DECEMBER, 1909 fj^r^^^^^^^^Y s2T*L--Z. A SHORT HISTORY OP THE Academy of Natural Sciences PHILADELPHIA BY EDWARD J. NOLAN, M.D. Recording Secretary and Librarian PHILADELPHIA THE ACADEMY OF NATURAL SCIENCES DECEMBER, 1909 qt-U npHIS brief history of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia was prepared as a contribution to the volume issued in commemoration of Founders' Week, so successfully celebrated from the fourth to the tenth of ^ October, 1908. fO The length of the article was determined by the number of pages available in the distribution of the matter composing the book and the story is, therefore, necessarily "short." The Notices of Morton and have I Euschenberger been of assistance in preparing the earlier portion. The sketch may be regarded as merely preliminary ^ to a detailed history of the Academy to be issued in - ^ connection with the proposed celebration of the Cente- g nary of the society in 1912. It is sent out in this form ^ with the hope that it will, by eliciting comment, criti- - cism, and perhaps correction, help to make the larger *l work of more permanent value. Any assistance to this end will be gratefully accepted by the author. EDWARD J. NOLAN THE ACADEMY OF NATURAL SCIENCES OF PHILADELPHIA, November, 1909. 310140 The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia By EDWARD J.