Notes on Ṛgveda 1.164.20-22 Per-Johan Norelius

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

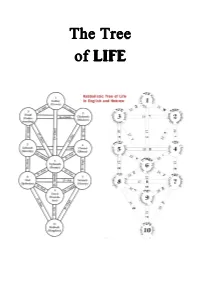

The Tree of LIFE

The Tree of LIFE ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ ~ 4 ~ Trees of Life. From the highest antiquity trees were connected with the gods and mystical forces in nature. Every nation had its sacred tree, with its peculiar characteristics and attributes based on natural, and also occasionally on occult properties, as expounded in the esoteric teachings. Thus the peepul or Âshvattha of India, the abode of Pitris (elementals in fact) of a lower order, became the Bo-tree or ficus religiosa of the Buddhists the world over, since Gautama Buddha reached the highest knowledge and Nirvâna under such a tree. The ash tree, Yggdrasil, is the world-tree of the Norsemen or Scandinavians. The banyan tree is the symbol of spirit and matter, descending to the earth, striking root, and then re-ascending heavenward again. The triple- leaved palâsa is a symbol of the triple essence in the Universe - Spirit, Soul, Matter. The dark cypress was the world-tree of Mexico, and is now with the Christians and Mahomedans the emblem of death, of peace and rest. The fir was held sacred in Egypt, and its cone was carried in religious processions, though now it has almost disappeared from the land of the mummies; so also was the sycamore, the tamarisk, the palm and the vine. The sycamore was the Tree of Life in Egypt, and also in Assyria. It was sacred to Hathor at Heliopolis; and is now sacred in the same place to the Virgin Mary. Its juice was precious by virtue of its occult powers, as the Soma is with Brahmans, and Haoma with the Parsis. -

The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen

The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen To cite this version: Arlo Griffiths, Annette Schmiedchen. The Atharvaveda and its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and philological papers on a Vedic tradition. Arlo Griffiths; Annette Schmiedchen. 11, Shaker, 2007, Indologica Halensis, 978-3-8322-6255-6. halshs-01929253 HAL Id: halshs-01929253 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01929253 Submitted on 5 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Griffiths, Arlo, and Annette Schmiedchen, eds. 2007. The Atharvaveda and Its Paippalādaśākhā: Historical and Philological Papers on a Vedic Tradition. Indologica Halensis 11. Aachen: Shaker. Contents Arlo Griffiths Prefatory Remarks . III Philipp Kubisch The Metrical and Prosodical Structures of Books I–VII of the Vulgate Atharvavedasam. hita¯ .....................................................1 Alexander Lubotsky PS 8.15. Offense against a Brahmin . 23 Werner Knobl Zwei Studien zum Wortschatz der Paippalada-Sam¯ . hita¯ ..................35 Yasuhiro Tsuchiyama On the meaning of the word r¯as..tr´a: PS 10.4 . 71 Timothy Lubin The N¯ılarudropanis.ad and the Paippal¯adasam. hit¯a: A Critical Edition with Trans- lation of the Upanis.ad and Nar¯ ayan¯ . a’s D¯ıpik¯a ............................81 Arlo Griffiths The Ancillary Literature of the Paippalada¯ School: A Preliminary Survey with an Edition of the Caran. -

Ancient Wisdom, Modern Life Mount Soma Timeline

Mount Soma Ancient Wisdom, Modern Life Mount Soma Timeline Dr. Michael Mamas came across the information about building an Enlightened City. 1985 Over time, it turned into his Dharmic purpose. November, 2002 The founders of Mount Soma came forth to purchase land. May, 2003 Began cutting in the first road at Mount Soma, Mount Soma Blvd. January, 2005 The first lot at Mount Soma was purchased. May, 2005 First paving of Mount Soma’s main roads. April, 2006 Dr. Michael Mamas had the idea of a Shiva temple at Mount Soma. Marcia and Lyle Bowes stepped forward with the necessary funding to build Sri October, 2006 Somesvara Temple. January, 2007 Received grant approval from Germeshausen Foundation to build the Visitor Center. July, 2007 Received first set of American drawings for Sri Somesvara Temple from the architects. Under the direction of Sthapati S. Santhanakrishnan, a student and relative of Dr. V. July, 2007 Ganapati Sthapati, artisans in India started carving granite for Sri Somesvara Temple. October, 2007 First house finished and occupied at Mount Soma. January, 2008 Groundbreaking for Visitor Center. May, 2008 146 crates (46 tons) of hand-carved granite received from India at Mount Soma. July, 2008 Mount Soma inauguration on Guru Purnima. July/August, 2008 First meditation retreat and class was held at the Visitor Center. February, 2009 Mount Soma Ashram Program began. July, 2009 Started construction of Sri Somesvara Temple. January, 2010 Received grant approval from Germeshausen Foundation to build the Student Union. August, 2010 American construction of Sri Somesvara Temple completed. Sthapati and shilpis arrived to install granite and add Vedic decorative design to Sri October, 2010 Somesvara Temple. -

Sources of Mythology: National and International

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & EBERHARD KARLS UNIVERSITY, TÜBINGEN SEVENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY SOURCES OF MYTHOLOGY: NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL MYTHS PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 15-17, 2013 Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany Conference Venue: Alte Aula Münzgasse 30 72070, Tübingen PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, MAY 15 08:45 – 09:20 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:20 – 09:40 OPENING ADDRESSES KLAUS ANTONI Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany JÜRGEN LEONHARDT Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany 09:40 – 10:30 KEYNOTE LECTURE MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA MARCHING EAST, WITH A DETOUR: THE CASES OF JIMMU, VIDEGHA MATHAVA, AND MOSES WEDNESDAY MORNING SESSION CHAIR: BORIS OGUIBÉNINE GENERAL COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY AND METHODOLOGY 10:30 – 11:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Saint Petersburg, Russia UNNOTICED EURASIAN BORROWINGS IN PERUVIAN FOLKLORE 11:00 – 11:30 EMILY LYLE University of Edinburgh, UK THE CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN INDO-EUROPEAN AND CHINESE COSMOLOGIES WHEN THE INDO-EUROPEAN SCHEME (UNLIKE THE CHINESE ONE) IS SEEN AS PRIVILEGING DARKNESS OVER LIGHT 11:30 – 12:00 Coffee Break 12:00 – 12:30 PÁDRAIG MAC CARRON RALPH KENNA Coventry University, UK SOCIAL-NETWORK ANALYSIS OF MYTHOLOGICAL NARRATIVES 2 NATIONAL MYTHS: NEAR EAST 12:30 – 13:00 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia FOUR STORIES OF THE FLOOD IN SUMERIAN LITERARY TRADITION 13:00 – 14:30 Lunch Break WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON SESSION CHAIR: YURI BEREZKIN NATIONAL MYTHS: HUNGARY AND ROMANIA 14:30 – 15:00 ANA R. CHELARIU New Jersey, USA METAPHORS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF MYTHICAL LANGUAGE - WITH EXAMPLES FROM ROMANIAN MYTHOLOGY 15:00 – 15:30 SAROLTA TATÁR Peter Pazmany Catholic University of Hungary A PECHENEG LEGEND FROM HUNGARY 15:30 – 16:00 MARIA MAGDOLNA TATÁR Oslo, Norway THE MAGIC COACHMAN IN HUNGARIAN TRADITION 16:00 – 16:30 Coffee Break NATIONAL MYTHS: AUSTRONESIA 16:30 – 17:00 MARIA V. -

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots

Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots Buddhism (Buddha) Followed by Hindūism (Kṛṣṇā) The religion of the Vedic period (also known as Vedism or Vedic Brahmanism or, in a context of Indian antiquity, simply Brahmanism[1]) is a historical predecessor of Hinduism.[2] Its liturgy is reflected in the Mantra portion of the four Vedas, which are compiled in Sanskrit. The religious practices centered on a clergy administering rites that often involved sacrifices. This mode of worship is largely unchanged today within Hinduism; however, only a small fraction of conservative Shrautins continue the tradition of oral recitation of hymns learned solely through the oral tradition. Texts dating to the Vedic period, composed in Vedic Sanskrit, are mainly the four Vedic Samhitas, but the Brahmanas, Aranyakas and some of the older Upanishads (Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Chāndogya, Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana) are also placed in this period. The Vedas record the liturgy connected with the rituals and sacrifices performed by the 16 or 17 shrauta priests and the purohitas. According to traditional views, the hymns of the Rigveda and other Vedic hymns were divinely revealed to the rishis, who were considered to be seers or "hearers" (shruti means "what is heard") of the Veda, rather than "authors". In addition the Vedas are said to be "apaurashaya", a Sanskrit word meaning uncreated by man and which further reveals their eternal non-changing status. The mode of worship was worship of the elements like fire and rivers, worship of heroic gods like Indra, chanting of hymns and performance of sacrifices. The priests performed the solemn rituals for the noblemen (Kshsatriya) and some wealthy Vaishyas. -

India's "Tīrthas": "Crossings" in Sacred Geography

India's "Tīrthas": "Crossings" in Sacred Geography The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Eck, Diana L. 1981. India's "Tīrthas": "Crossings" in sacred geography. History of Religions 20 (4): 323-344. Published Version http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062459 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:25499831 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA DianaL.Eck INDIA'S TIRTHAS: "CROSSINGS" IN SACRED GEOGRAPHY One of the oldest strands of the Hindu tradition is what one might call the "locative" strand of Hindu piety. Its traditions of ritual and reverence are linked primarily to place-to hill- tops and rock outcroppings, to the headwaters and confluences of rivers, to the pools and groves of the forests, and to the boundaries of towns and villages. In this locative form of religiousness, the place itself is the primary locus of devotion, and its traditions of ritual and pilgrimage are usually much older than any of the particular myths and deities which attach to it. In the wider Hindu tradition, these places, par- ticularly those associated with waters, are often called tirthas, and pilgrimage to these tirthas is one of the oldest and still one of the most prominent features of Indian religious life. A tZrtha is a "crossing place," a "ford," where one may cross over to the far shore of a river or to the far shore of the worlds of heaven. -

Read and History of Eurasia

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & CENTER OF EXCELLENCE IN ESTONIAN STUDIES THIRTEENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY MYTHOLOGY OF METAMORPHOSES: COMPARATIVE & THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS June 10-14, 2019 Estonian Literary Museum Vanemuise 42, 51003, Tartu, Estonia ELM Scholarly Press Tartu, Estonia Editor: Nataliya Yanchevskaya Layout: Nataliya Yanchevskaya, Diana Kahre Cover: Andres Kuperjanov, Nataliya Yanchevskaya International committee: Yury Berezkin, Mare Kõiva, Kazuo Matsumura, Michael Witzel, Nataliya Yanchevskaya Local committee: Karl Jaago, Tõnno Jonuks, Mare Kõiva, Anne Ostrak, Piret Voolaid http://www.compmyth.org/ https://www.folklore.ee/rl/fo/konve/2019/mytholog/ Supported by the International Association for Comparative Mythology (IACM), Estonian Cultural Foundation, Estonian Literary Museum, the Centre of Excellence in Estonian Studies (CEES, European Regional Development Fund), ASTRA (EKMDHUM, European Regional Development Fund), and is related to research projects IRG 22-5 (Estonian Research Council). ISBN 978-9949-677-16-0 (print) ISBN 978-9949-677-17-7 (pdf) © Estonian Literary Museum © IACM © Authors © Andres Kuperjanov, Nataliya Yanchevskaya 2 Mythology of Metamorphoses: Comparative & Theoretical Perspectives The 13th Annual International Conference on Comparative Mythology of the International Association for Comparative Mythology & The 8th Annual Conference of the Center of Excellence in Estonian Studies June 10-14, 2019, Estonian Literary Museum, Tartu, Estonia Creative development of mythologies has been part of the human culture since time immemorial. Myths explain the origin of humans and other beings, the Earth and the Sky, and the world as a whole. Mythological reality is fluid and is subject to metamorphosis. Mythological characters shift their shape; human and supernatural beings undergo all kinds of transitions; the world and myth are constantly changing. -

The World-Ash Wonder Tree

by Frater Apollonius 4°=7□ ATAT The World-Ash Wonder Tree My adepts stand upright; their head above the heavens, their feet below the hells. —Liber XC:40 Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law. The „axis mundi‟ is a geographic and mathematical symbol used by Hermeticists to represent the center of the world where the heavens connect with the earth; „as above, so below‟. It is represented in the Gnostic Mass by the Rod that the Priest holds. Yet it also represents an anatomical trinity representing the birthing process. As a feminine symbol, it is represented by the umbilical chord that connects the child to the womb; as a masculine symbol, it is represented by the phallus and as a unisex symbol, it represented by the navel—the sacred omphalos. As the Tree-of-Life is presented as the connecting link between humanity and that which we call divine, the „World Tree‟ is represented in several religions and mythological systems as the tree that supports the heavens and is yet rooted in the Earth. This of course includes the „underworld‟ that for us today, is the Astral Plane. The Tree-of-Life then, is an archetypal map of our Astral Bodies. As an evolving symbol, it has had its own ontological development in Western culture. The tree reaches from the underworld to the sensory and material world, on into the starry sky. It is this same tree represented in the Book of Revelation: 22:1And he showed me a river of water of life, bright as crystal, proceeding out of the throne of God and of the Lamb, 22:2in the midst of the street thereof. -

The Historical Development of Hinduism

/=ir^Tr TTTF^ i'—"i Tr=^ JA rr \7 ^isrii ^iH^tV 0vtaivt Soetei^ z)floito^i^€t.pli ac-omtdSc/erc-es ^/Lu^mhe^v trofi^r XT TT(f==3P=r N JIJLY=AU u o ^aL 47 dtunXev 9^4 The Open Court Founded by Edward C. Hegeler Editors: GUSTAVE K. CARUS ELISABETH CARUS SECOND MONOGRAPH SERIES OF THE NEW ORIENT SOCIETY OF AMERICA NUMBER FOUR INDIA EDITED BY WALTER E. CLARK Published Monthly: January, June, September, December April-May, July- August, October-November Bi-monthly : February-March, THE OPEN COURT PUBLISHING COMPANY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 149 EAST HURON STREET copies, 50c Subscription rates: $3.00 a year, 35c a copy, monograph the Post Office Entered as Secona-Class matter April 12. 1933. at 1879. at Chicago, Illinois, under Act of March 3, COPYRIGHT THK Ol'EN COVRT PUBLISUIXG CO. 1933 CONTENTS The Historical Development oe Hinduism 281 Hinduism 290 Hinduism as Religion and Philosophy 294 Caste 308 muhammadan conquest and influence on hlnduism 322 British Conquest and Government 326 Indian Nationalism 328 fiiHiiniiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiyiiiififflriiiiiiiiiHiiirnriiiiiiiiiintiiPiiiiiiiiiiiiifiiiiijiiiiiii^^ ^^^^ ^.^pg^ i THE NEW ORIENT IN BOOKS <>:;' ^ W^iTifTrrrr ^ Philosophy of Hindu Sadhaiia. By Nalini Kanta Brahma, with a foreword by Sir Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan. London. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner, and Co. Ltd. 1933. Pp. xvi 333. In this volume on Hindu philosophy. Nalini Kanta Brahma has endeav- oured to point out the significance of the course of discipline prescribed by the different religious systems for the attainment of spiritual enlightenment. His interest is in the practical side of Hinduism and in showing the essential con- nection between theory and practice, although he gives a clear discussion of the philosophical concepts. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr. -

Hymns to the Mystic Fire

16 Hymns to the Mystic Fire VOLUME 16 THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO © Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust 2013 Published by Sri Aurobindo Ashram Publication Department Printed at Sri Aurobindo Ashram Press, Pondicherry PRINTED IN INDIA Hymns To The Mystic Fire Publisher’s Note The present volume comprises Sri Aurobindo’s translations of and commentaries on hymns to Agni in the Rig Veda. It is divided into three parts: Hymns to the Mystic Fire: The entire contents of a book of this name that was published by Sri Aurobindo in 1946, consisting of selected hymns to Agni with a Fore- word and extracts from the essay “The Doctrine of the Mystics”. Other Hymns to Agni: Translations of hymns to Agni that Sri Aurobindo did not include in the edition of Hymns to the Mystic Fire published during his lifetime. An appendix to this part contains his complete transla- tions of the first hymn of the Rig Veda, showing how his approach to translating the Veda changed over the years. Commentaries and Annotated Translations: Pieces from Sri Aurobindo’s manuscripts in which he commented on hymns to Agni or provided annotated translations of them. Some translations of hymns addressed to Agni are included in The Secret of the Veda, volume 15 of THE COMPLETE WORKS OF SRI AUROBINDO. That volume consists of all Sri Aurobindo’s essays on and translations of Vedic hymns that appeared first in the monthly review Arya between 1914 and 1920. His writings on the Veda that do not deal primarily with Agni and that were not published in the Arya are collected in Vedic and Philological Studies, volume 14 of THE COMPLETE WORKS. -

Africana Studies Review

AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 ON THE COVER DETAIL FROM A PIECE OF THE WOODEN QUILTS™ COLLECTION BY NEW ORLEANS- BORN ARTIST AND HOODOO MAN, JEAN-MARCEL ST. JACQUES. THE COLLECTION IS COMPOSED ENTIRELY OF WOOD SALVAGED FROM HIS KATRINA-DAMAGED HOME IN THE TREME SECTION OF THE CITY. ST. JACQUES CITES HIS GRANDMOTHER—AN AVID QUILTER—AND HIS GRANDFATHER—A HOODOO MAN—AS HIS PRIMARY INFLUENCES AND TELLS OF HOW HEARING HIS GRANDMOTHER’S VOICE WHISPER, “QUILT IT, BABY” ONE NIGHT INSPIRED THE ACCLAIMED COLLECTION. PIECES ARE NOW ON DISPLAY AT THE AMERICAN FOLK ART MUSEUM AND OTHER VENUES. READ MORE ABOUT ST. JACQUES’ JOURNEY BEGINNING ON PAGE 75 COVER PHOTOGRAPH BY DEANNA GLORIA LOWMAN AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 ISSN 1555-9246 AFRICANA STUDIES REVIEW JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN STUDIES SOUTHERN UNIVERSITY AT NEW ORLEANS VOLUME 6 NUMBER 1 SPRING 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Africana Studies Review ....................................................................... 4 Editorial Board ....................................................................................................... 5 Introduction to the Spring 2019 Issue .................................................................... 6 Funlayo E. Wood Menzies “Tribute”: Negotiating Social Unrest through African Diasporic Music and Dance in a Community African Drum and Dance Ensemble .............................. 11 Lisa M. Beckley-Roberts Still in the Hush Harbor: Black Religiosity as Protected Enclave in the Contemporary US ................................................................................................ 23 Nzinga Metzger The Tree That Centers the World: The Palm Tree as Yoruba Axis Mundi ........