The Tree of Life Design – Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson: Two Carpets Essential Questions

Lesson: Two Carpets Essential Questions: Why are carpets important in Islamic cultures? What are the basic characteristics of West Asian carpet design? What are the similarities and differences between the Ottoman Turkish and Iranian carpets discussed in this lesson? Learning experience: Students will become familiar with two roughly contemporaneous carpets, one from Ottoman Anatolia and one from Iran. They will analyze their design and learn about some of the aesthetic priorities of the people who created them. Anticipatory set: In your house, your apartment, or your room: what kind of objects do you surround yourself with? Which are useful? Which are decorative? Which are both? Context: Carpets have been made for thousands of years throughout Central and West Asia. Flat-woven textiles (kilims—carpets without pile) were made in Turkey at least as early as 7000 BCE. The oldest surviving woolen pile carpet dates from the fifth century BCE, found in a burial site in the Altai mountains of southern Siberia. For pastoral nomadic inhabitants of the Eurasian steppe, carpets served as “floor coverings, prayer mats, tent decorations, canopies, as symbols of power, privilege and riches” (Abas 2004: 11). In the sedentary world of cities, towns, and farming villages, carpets were also more than floor covering. They were "an integral part of one’s living arrangements, one which took the place of chairs, beds, and sometimes tables” (www: Erdmann). Carpets, in short were necessities, not merely decorations, and so were worth the great care that was lavished on them. Those belonging to the wealthy never remained in one place all the time. -

Persian Collections

Size: 1 (Ft) = 30cm • SELL • TRADE PERSIAN • WASH MASTER PIECE MASTER PIECE • RESTORE NEW AND ANTIQUE 489594-P CARPETS www.persiancollections.com Collections THE fine persian carpet gallery Open 7 Days A Week Desa Sri Hartamas 32-2 & 34-2, Jalan 25/70A 6. Super Fine Tabriz, signed by Master Weaver. 11. Showroom 12. Great Stock. BIGGEST CARPET Kurk wool & silk on silk base, 400 x 600 cm. Take 8 years to weave. MUST SEE!!! Desa Sri Hartamas 50480 Kuala Lumpur SALE ☎ 03-2300 6966 Bangsar Shopping Centre 50% - 75% F4A, 1st Floor (East Wing) Bangsar Shopping Centre off 59000 Kuala Lumpur ☎ 03-2094 6966 Holiday Villa - Jln Ampang BGM-12, Ground Floor Megan Embassy (Holiday Villa) Jln Ampang, K.L. ☎ 012-308 0068 5. Super Fine Qum Silk, signed by Master Weaver. 7. Large selection on extra large carpet. 6th June 20th July 2008 13. Great Turnover! New Stock Arrive Monthly. 14. See Our Extensive Stock Selection. SALE Silk on silk base, 250 x 350 cm. Take more than 8 years to weave. MUST SEE!!! BRINGING WONDERS OF PERSIA TO YOUR HOME MORE THAN 5,000 CHOICE OF PERSIAN CARPETS ON SALE MASTER PIECE COLLECTABLE ITEM 1. Tribal Kilim Stool. 2. Fine Persian Tabriz. Dining Room Size. 8. Super Fine Qum Silk, sign by Master Weaver. 15. Super Fine Nain. 16. Super Fine Tabriz. Silk on silk base, 350 x 500 cm. Take 10-12 years to weave. DO NOT MISS!!! Wool & silk on cotton base, 500 x 800 cm Wool & silk on cotton base, 300 x 400 cm BEST BUY RM ***** MASTER PIECE 3. -

Prayer Cards (709)

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations A Che in China A'ou in China Population: 43,000 Population: 2,800 World Popl: 43,000 World Popl: 2,800 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: Tibeto-Burman, other People Cluster: Tai Main Language: Ache Main Language: Chinese, Mandarin Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.00% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net Source: Operation China, Asia Harvest www.joshuaproject.net Source: Operation China, Asia Harvest "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations A-Hmao in China Achang in China Population: 458,000 Population: 35,000 World Popl: 458,000 World Popl: 74,000 Total Countries: 1 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: Miao / Hmong People Cluster: Tibeto-Burman, other Main Language: Miao, Large Flowery Main Language: Achang Main Religion: Christianity Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Significantly reached Status: Partially reached Evangelicals: 75.0% Evangelicals: 7.0% Chr Adherents: 80.0% Chr Adherents: 7.0% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Anonymous Source: Wikipedia "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Achang, Husa in China Adi -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

The Construction of Pagan Identity in Lithuanian “Pagan Metal” Culture

VYTAUTO DIDŢIOJO UNIVERSITETAS SOCIALINIŲ MOKSLŲ FAKULTETAS SOCIOLOGIJOS KATEDRA Agnė Petrusevičiūtė THE CONSTRUCTION OF PAGAN IDENTITY IN LITHUANIAN “PAGAN METAL” CULTURE Magistro baigiamasis darbas Socialinės antropologijos studijų programa, valstybinis kodas 62605S103 Sociologijos studijų kryptis Vadovas Prof. Ingo W. Schroeder _____ _____ (Moksl. laipsnis, vardas, pavardė) (Parašas) (Data) Apginta _________________________ ______ _____ (Fakulteto/studijų instituto dekanas/direktorius) (Parašas) (Data) Kaunas, 2010 1 Table of contents SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................................ 4 SANTRAUKA .................................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 8 I. THEORIZING ―SUBCULTURE‖: LOOKING AT SCIENTIFIC STUDIES .............................. 13 1.1. Overlooking scientific concepts in ―subcultural‖ research ..................................................... 13 1.2. Assumptions about origin of ―subcultures‖ ............................................................................ 15 1.3 Defining identity ...................................................................................................................... 15 1.3.1 Identity and ―subcultures‖ ................................................................................................ -

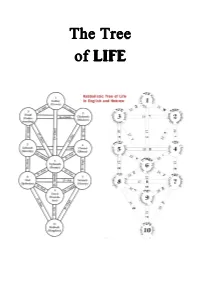

The Tree of LIFE

The Tree of LIFE ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ ~ 4 ~ Trees of Life. From the highest antiquity trees were connected with the gods and mystical forces in nature. Every nation had its sacred tree, with its peculiar characteristics and attributes based on natural, and also occasionally on occult properties, as expounded in the esoteric teachings. Thus the peepul or Âshvattha of India, the abode of Pitris (elementals in fact) of a lower order, became the Bo-tree or ficus religiosa of the Buddhists the world over, since Gautama Buddha reached the highest knowledge and Nirvâna under such a tree. The ash tree, Yggdrasil, is the world-tree of the Norsemen or Scandinavians. The banyan tree is the symbol of spirit and matter, descending to the earth, striking root, and then re-ascending heavenward again. The triple- leaved palâsa is a symbol of the triple essence in the Universe - Spirit, Soul, Matter. The dark cypress was the world-tree of Mexico, and is now with the Christians and Mahomedans the emblem of death, of peace and rest. The fir was held sacred in Egypt, and its cone was carried in religious processions, though now it has almost disappeared from the land of the mummies; so also was the sycamore, the tamarisk, the palm and the vine. The sycamore was the Tree of Life in Egypt, and also in Assyria. It was sacred to Hathor at Heliopolis; and is now sacred in the same place to the Virgin Mary. Its juice was precious by virtue of its occult powers, as the Soma is with Brahmans, and Haoma with the Parsis. -

188189399.Pdf

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Zhytomyr State University Library МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ЖИТОМИРСЬКИЙ ДЕРЖАВНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ ІМЕНІ ІВАНА ФРАНКА Кваліфікаційна наукова праця на правах рукопису КУКУРЕ СОФІЯ ПАВЛІВНА УДК 213:257:130.11 ДИСЕРТАЦІЯ ЕТНІЧНІ РЕЛІГІЇ БАЛТІЙСЬКИХ НАРОДІВ ЯК ЧИННИК НАЦІОНАЛЬНО-КУЛЬТУРНОЇ ІДЕНТИФІКАЦІЇ 09.00.11 – релігієзнавство філософські науки Подається на здобуття наукового ступеня кандидата філософських наук Дисертація містить результати власних досліджень. Використання ідей, результатів і текстів інших авторів мають посилання на відповідне джерело _______________ Кукуре С. П. Науковий керівник – доктор історичних наук, професор Гусєв Віктор Іванович Житомир – 2018 2 АНОТАЦІЯ Кукуре С. П. Етнічні релігії балтійських народів як чинник національно-культурної ідентифікації. – Кваліфікаційна наукова праця на правах рукопису. Дисертація на здобуття наукового ступеня кандидата філософських наук (доктора філософії) за фахом 09.00.11 «Релігієзнавство, філософські науки». – Житомирський державний університет імені Івана Франка Міністерства освіти і науки України, Житомир, 2019. Вперше в українському релігієзнавстві досліджено етнічні релігії балтійських народів, які виступали та виступають чинником національно- культурної ідентифікації в зламні моменти їх історії, коли виникала загроза асиміляції або зникнення (насильницька християнізації часів Середньовіччя, становлення державності в першій половині ХХ століття), а також на сучасному етапі, коли -

Sustainability of Handwoven Carpets in Turkey: the Context of the Weaver

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2006 Sustainability of Handwoven Carpets in Turkey: The Context of the Weaver Kimberly Berman University, Ithaca, NY Charlotte Jirousek Cornell University, Ithaca, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Design Commons Berman, Kimberly and Jirousek, Charlotte, "Sustainability of Handwoven Carpets in Turkey: The Context of the Weaver" (2006). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 340. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/340 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Sustainability of Handwoven Carpets in Turkey: The Context of the Weaver Kimberly Berman, graduate student, Charlotte Jirousek, Assoc. Professor Department of Textiles and Apparel Cornell Department of Textiles and Apparel University, Ithaca, NY Cornell University, Ithaca, NY Forms of Production Past research, conducted mainly in the 1970s and 1980s, has identified three forms of production in which carpets are woven as commodities1. These are petty-commodity production, the putting-out system, and workshop production. Petty-commodity production involves weaving in the home, with the male head of the household or other male relatives selling the finished product to a carpet dealer or at a local or regional market (fig. 1). The family owns the loom and other weaving supplies, and family members purchase or prepare the yarn themselves. -

Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2020 Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia Zahra F. Syed The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3785 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DEVOTIONAL LITERATURE OF THE PROPHET MUHAMMAD IN SOUTH ASIA by ZAHRA SYED A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in [program] in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2020 © 2020 ZAHRA SYED All Rights Reserved ii Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia by Zahra Syed This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Middle Eastern Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. _______________ _________________________________________________ Date Kristina Richardson Thesis Advisor ______________ ________________________________________________ Date Simon Davis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Devotional Literature of the Prophet Muhammad in South Asia by Zahra Syed Advisor: Kristina Richardson Many Sufi poets are known for their literary masterpieces that combine the tropes of love, religion, and the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). In a thorough analysis of these works, readers find that not only were these prominent authors drawing from Sufi ideals to venerate the Prophet, but also outputting significant propositions and arguments that helped maintain the preservation of Islamic values, and rebuild Muslim culture in a South Asian subcontinent that had been in a state of colonization for centuries. -

Pilgrimage | the Haram at Mecca and the Ka'ba

Pilgrimage | The Haram at Mecca and the Ka’ba 'The Ka'ba is the qibla of Islam.' The Ka'ba is the qibla (direction of prayer) of Islam. It is also at the heart of the Hajj and everyone who visits the Haram at Mecca has to circumvent the Ka'ba seven times as part of the prescribed pilgrimage ritual. The Ka'ba has many names in the Islamic tradition, among them: al-Masjid al-Haram (The Sacred Mosque, referring to the mosque within the precinct of the Ka'ba) and al-Bayt al-Atiq (the Ancient House). The Ka'ba is an almost square structure: 9.29 m on its north side, 12.15 m on its west, 10.25 m on its south side, and 11.88 m on its east side. It is 15 m high and has only one access door on the east face that is 2 m above ground level. Name: Ceramic tile panel Dynasty: Hegira 1087 / AD 1676 Ottoman Details: Museum of Islamic Art Cairo, Egypt Justification: A tile panel showing a ground-plan for the Holy Mosque at Mecca with the Ka'ba in the centre. Name: Painting Dynasty: Hegira early 12th century / AD early 18th century Ottoman Details: Uppsala University Library Uppsala, Sweden Justification: A topographical painting of the Haram shown with details of entrances, minarets and the surrounding sites. Name: Astronomical instrument: Qiblanuma Dynasty: Hegira 1151 / AD 1738 Ottoman Details: Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts Sultanahmet, Istanbul, Turkey Justification: A compass (qiblanuma) that determined the direction of prayer (qibla) and the correct route to Mecca. -

Treasures from Near Eastern Looms

The Bowdoin College Library Treasures from Near Eastern Looms ERNEST H. ROBERTS BRUNSWICK, MAINE 1981 Bowdoin College Museum of Art Brunswick, Maine September 11, 1981 to November 22, 1981 The Textile Museum Washington, District of Columbia December 11, 1981 to February 6, 1982 Cover: Carpel Fnn>incni, Caucasian, Dagistan area, ca. 1850 Photographs by Robert H. Stillwell Design by Michael W. Mahan Printed byJ.S. McCarthy Co., Inc., Augusta, Maine Copyright © 1981 by Ernest H. Roberts Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 81-68474 ISBN: 0-916606-02-3 Portions of this catalogue are reprinted in altered form from other publications. We are indebted to the following institutions for per- mission to use their material: to the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio, for the chapter introductions and descriptions of plates 12, 19, 24, 28, 63, and 65, which appeared in "Catalogue of Islamic Carpets," Allen An Museum Bulletin 3 (1978-1979) by Ernest H. Roberts; to The Textile Museum, Washington, D.C., for glossary entries and drawings from "Definitions and Explana- tions," a section of Early Caucasian Ru^s by Charles Grant Ellis, published by that museum in 1975, and for the loan of the map which appears on page 61 of this book; to the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Nebraska, for descriptions of plates 28, 35, 44, 57, and 67 from A Rich Inheritance: Oriental Ruj^s oj 19th and Early 20th Centuries, published by that museum in 1974; and to the Near Eastern Art Research Center, Inc., for the description of plate 68 from Islamic Carpets by Joseph V. -

Pre-Proto-Iranians of Afghanistan As Initiators of Sakta Tantrism: on the Scythian/Saka Affiliation of the Dasas, Nuristanis and Magadhans

Iranica Antiqua, vol. XXXVII, 2002 PRE-PROTO-IRANIANS OF AFGHANISTAN AS INITIATORS OF SAKTA TANTRISM: ON THE SCYTHIAN/SAKA AFFILIATION OF THE DASAS, NURISTANIS AND MAGADHANS BY Asko PARPOLA (Helsinki) 1. Introduction 1.1 Preliminary notice Professor C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky is a scholar striving at integrated understanding of wide-ranging historical processes, extending from Mesopotamia and Elam to Central Asia and the Indus Valley (cf. Lamberg- Karlovsky 1985; 1996) and even further, to the Altai. The present study has similar ambitions and deals with much the same area, although the approach is from the opposite direction, north to south. I am grateful to Dan Potts for the opportunity to present the paper in Karl's Festschrift. It extends and complements another recent essay of mine, ‘From the dialects of Old Indo-Aryan to Proto-Indo-Aryan and Proto-Iranian', to appear in a volume in the memory of Sir Harold Bailey (Parpola in press a). To com- pensate for that wider framework which otherwise would be missing here, the main conclusions are summarized (with some further elaboration) below in section 1.2. Some fundamental ideas elaborated here were presented for the first time in 1988 in a paper entitled ‘The coming of the Aryans to Iran and India and the cultural and ethnic identity of the Dasas’ (Parpola 1988). Briefly stated, I suggested that the fortresses of the inimical Dasas raided by ¤gvedic Aryans in the Indo-Iranian borderlands have an archaeological counterpart in the Bronze Age ‘temple-fort’ of Dashly-3 in northern Afghanistan, and that those fortresses were the venue of the autumnal festival of the protoform of Durga, the feline-escorted Hindu goddess of war and victory, who appears to be of ancient Near Eastern origin.