Sustainability of Handwoven Carpets in Turkey: the Context of the Weaver

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rugs Weave New Lives

Rugs Weave Scholar-in- New Lives Residence n 1978, German chemist Dr. Harald Boehmer sparked “The Great IAnatolian Rug Revolution,” transforming the entire Turkish rug industry. Even more than an industrial revolu tion, it has become a cultural survival project known as DOBAG, a Turkish acronym for Nat ural Dye Research and Development Project, which has restored the ancient art of handwo ven carpets and established the first-ever woman’s rug weaving cooperative in the Islamic world. Boehmer will give a lecture, Nomads of Anatolia, at 7 p.m., Saturday, Sept. 13, in Hudson Audi torium, Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art. The lecture is free and open to the public as part of JCCC’s Scholar-in-Residence program. A reception with Boehmer begins at 6 p.m. During his Sept. 13-17 residency, Boehmer will also address JCCC textile classes. Boehmer’s passion for native rugs began when he was teaching in Turkey. Using thin-layer chromatography, the chemist was able to ana lyze the dyes used in old Turkish rugs and match the vibrant colors to their original plant sources. Under Boehmer’s guidance, weavers stopped buying petroleum-based dyes and returned to Indeed, the DOBAG Project has raised the the natural plant dyes for their wool. The profit- social and economic status of women. Villagers Anatolain rugs are sharing cooperative DOBAG began and now are no longer forced to move to cities to look for displayed here, supports about 400 families in western Turkey. work. A participating weaver must send her photographed by children to school, and no child labor is Boehmer in 2007. -

The Tree of Life Design – Part 1

S. Busatta– The Tree of Life Design – Part 1 Cultural Anthropology 205 – 220 The Tree of Life Design From Central Asia to Navajoland and Back (With a Mexican Detour) Part 1 Sandra Busatta Antrocom-Onlus sez. Veneto The Tree of Life design is thought to be originated in Central Asia possibly from shamanic cultures, and can be seen as a favorite pattern in many carpets and rugs produced in a huge area, from Afghanistan to Eastern Europe. From the Middle East, together with other Christian and Moorish designs, it was imported to Central America where it mixed with the local versions of Tree of Life. Traders who brought Oriental carpet patterns to be reproduced by Navajo weavers made it known to them, but it was only after the 1970s that the design has had a real success together with other pictorial rugs. Introduction In the late 1970s for the first time I saw a number of samples showing the so-called Tree of Life design embellishing the walls of a restaurant in the Navajo reservation. In one or two trading posts and art galleries in the Southwest I also saw some Tree of Life rugs made by Navajo weavers, and also some Zapotec imitations, sold almost clandestinely by a roadside vendor at a ridiculously low price. The shops selling Mexican artesanias, both in the US Southwest and in Mexico, however, displayed only a type of Tree of Life: a ceramic chandelier- like, very colorful item that had very little to do with the Tree of Life design in the Navajo rugs and their Zapotec imitations. -

The Space of the Anatolian Carpet, an Analytical Vision

275 Ismail Mahmoud, et al. The Space of the Anatolian Carpet, an Analytical Vision Prof. Ismail I. Mahmoud Textile Department, Faculty of Applied Arts, Helwan University, Egypt Ahmed Abdel Ghany Master Student, Faculty of Applied Arts. Helwan University, Printing, Egypt Abstract: Keywords: Anatolian rug designs are known to have a number of historical and aesthetic Space values. They certainly constitute a large portion of the body of existing oriental Anatolian rugs carpets. This study assumes that through an analytical investigation of their space; it will be easier for scholars to appreciate and comprehend the Anatolian rugs in Oriental rugs relation to their relevant layout, which will enable making new rug layouts with Composition similar aesthetic values. Composition principles Through a studious analysis of symbols used in Anatolian rugs, and comparing the use of space in the Anatolian and contemporary rug, a better understanding can be Rug Layout achieved of the sense and taste of aesthetics and ratio to spacing that would help Rug Design Anatomy predict the changes in carpet and rug spacing, so that new rug and carpet spacing Layout analysis methods can be introduced in a way that appeals to consumers. This study aims to analyze the layout of Anatolian rugs in accordance to design Anatolian rug layout basics; to help designers to better understand and develop rug layouts in a development systematic way. Along with studying the layouts, the focal standpoint of this study undergoes an artistic analysis of oriental rugs, covering discussions in various original studies and data sources. Furthermore, the research aims to further explore the motives related to the design and development of these rugs. -

Pre-Orientalism in Costume and Textiles — ISSN 1229-3350(Print) ISSN 2288-1867(Online) — J

Journal of Fashion Business Vol.22, No.6 Pre-Orientalism in Costume and Textiles — ISSN 1229-3350(Print) ISSN 2288-1867(Online) — J. fash. bus. Vol. 22, No. 6:39-52, December. 2018 Keum Hee Lee† https://doi.org/ 10.12940/jfb.2018.22.6.39 Dept. of Fashion Design & Marketing, Seoul Women’s University, Korea Corresponding author — Keum Hee Lee Tel : +82-2-970-5627 Fax : +82-2-970-5979 E-mail: [email protected] Keywords Abstract Pre-Orientalism, Orientalism, The objective of this study was to enhance understanding and appreciation of oriental fashion, Pre-Orientalism in costumes and textiles by revealing examples of Oriental cultural-exchange, influences in Europe from the 16th century to the mid-18th century through in-depth study. The research method used were the presentation and analysis of previous literature research and visual data. The result were as follows; Pre-Orientalism had been influenced by Morocco, Thailand, and Persia as well as Turkey, India, and China. In this study, Pre-Orientalism refers to oriental influence and oriental taste in Western Europe through cultural exchanges from the 16th century to the mid-18th century. The oriental costume was the most popular subspecies of fancy, luxury dress and was a way to show off wealth and intelligence. Textiles were used for decoration and luxury. The Embassy and the court in Versailles and Vienna led to a frenzy of oriental fashion. It appeared that European in the royal family and aristocracy of Europe had been accommodated without an accurate understanding of the Orient. Although in this study, the characteristics, factors, and impacts of Pre-Orientalism have not — been clarified, further study can be done. -

Vol. XXVIII, No. 3 March, 2021 Newsletter

View from the Fringe Newsletter of the New England Rug Society Vol. 28 No. 3 March 2021 www.ne-rugsociety.org March Meeting (Online): Stefano Ionescu, “Tracing the Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania” Meeting Details Date and Time: 11 AM (EST), on Saturday, March 13 Venue: Your desktop, laptop, or tablet! Directions: Jim Sampson 1 will email invitation links to members; to receive the Stefano Ionescu, examples, including Ushaks, Holbeins, Lottos, Selendis, and Zoom login, you must register and a view of Lotto a wealth of “Transylvanian” rugs. The presentation will draw before the meeting by clicking and small-pattern on his new ideas and latest findings about these carpets— on the link in Jim’s email. Holbein rugs including the nature of their “intentional imperfections.” He Non-members should email in Saint Margaret’s will conclude by showing some unpublished examples of the [email protected] Church, Mediaş, Bistritza collection held in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum to get an invitation link. Transylvania in Nuremberg, and will briefly report on a project of weaving high-quality Anatolian copies of these rugs, to be displayed Transylvania is the repository of the richest and best- in the Bistritza Parish. preserved group of small-format Anatolian rugs outside the Born in 1951 in Transylvania, Stefano has lived in Rome Islamic world—almost four hundred examples (including since 1975. An independent scholar, he is the major expert on the fragments) attributable to the golden age of Ottoman corpus of Anatolian rugs surviving in his homeland. His first rug weaving. On March 13, Stefano Ionescu will tell NERS book, Antique Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania (2005), was attendees and guests how these rugs arrived in Transylvania, awarded the Romanian Academy Prize in Art History. -

V3-87-95.Pdf

Current Research Journal of Social Sciences 3(2): 87-95, 2011 ISSN: 2041-3246 © Maxwell Scientific Organization, 2011 Received: January 13, 2011 Accepted: March 03, 2011 Published: March 30, 2011 The Principles of Ornament in Islamic Art and Effects of These Principles on the Turkish Carpet Art Sema Etikan Mugla Universty, Milas S2tk2 Koçman Vocational School, Weaving of Carpet and Kilim Programme, Mugla-Turkey Abstract: Islamic art reflects art work which is formed by combining earlier art perception in muslims living areas with Islamic prensiples. Islamic art can be understood as a synthesis however, it has also its own originality. The main characteristic to reflect the originality of this art is ornament style. This ornament art is applied similarly in every Islamic art work. In this study, it is aimed to tell the reflections of Islamic ornament art into Turkish carpet art. The elements of ornamaent in Islamic art formed by various types of calligraphy, geometric shapes and rich vegetal motifs are applied to produced works according to certain principles. The principles are eternity, abstraction, symmetric and repetition, arabesque (interlaced ornament) and bordering. Most of these principles are used together on the forming stage of the works The examples with basic characteristics of the principles of ornament in Islamic art have been seen on the Turkish carpet art. In this study the effect of Islamic ornament principles on Turkish carpets have been examined and explained with examples considering the historical development stages. Key words: Carpet, Islamic, Islamic art, ornament, motif, Turkish carpet art INTRODUCTION script in the ornament by means of examples and given information on ornament principles. -

Download Download

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 09, Issue 05, 2020: 39-46 Article Received: 20-04-2020 Accepted: 12-05-2020 Available Online: 20-05-2020 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v9i5.1914 Traditional Carpet-Rug Descriptions in the Paintings of Turkish Painters (post-1882 period)1 Müzeyyen TATLICI2, F.Nurcan SERT3 ABSTRACT Background: Carpet-rug art is an important material in Turkish culture and life. Anatolia's thousands of years of cultural heritage, folklore, and life have been processed not only in paintings but also in rugs in order to transfer it to its works, sometimes with realistic, sometimes impressionist or abstract interpretations. The first carpet samples were found in East Turkistan with the Pazırık tomb in the Altai in line with the examinations and information made in the various excavations and it is estimated that they were built in the BC 5-3 century. Objective: Seals identity that the carpet-rug lived in Anatolia in Turkey date is the record of relations with extant prior rights. The characteristics that convey past cultural experiences to today still continue. It enables culture to be passed down from generation to generation with its unique fabric shape and patterns. Method: With this research, it has been tried to be revealed the depictions of traditional rugs in carpets-rugs that were influenced in the works of Turkish painters the period after 1882 by literature scanning. Conclusion: As a result of the study, it is observed that the painters were not independent from the Turkish customs, traditions and culture while they were painting. -

Daun Curry 18 Material Submitted for Publication Will Not Be Returned Unless ”Handmade Rugs Are a Unique Artform” Specifically Requested

AREA THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ORIENTAL RUG IMPORTERS ASSOCIATION, INC. DESIGN FOCUS Daun Curry S P R I N G 2 0 1 5 $QJRUD8VKDN&ROOHFWLRQ70 4GRTQFWEVKQPUQHNCVGVJGCTN[VJEGPVWT[7UJCMU2TGOKWO#PIQTC YQQNKUDNGPFGFYKVJJKIJRNCVGCW#PCVQNKCPYQQNTGUWNVKPIKPJKIJEQNQT NWOKPQUKV[ +XII5RDG1:$WODQWD*$łłVDOHV#DQDGROUXJVFRPłZZZDQDGROUXJVFRP THEHE KKINGNGLLSEYY COLL LECTL ION VISIT US THIS SPRING HIGH POINT IHFC D-320 LOLOI R UGS.COM Your resource for fine hand-woven rugs 3901 Liberty Avenue North Bergen, New Jersey 07047 tel (201) 863-8888 • fax (201) 863-8898 [email protected] • www.teppteamusa.com From the President’s Desk Dear Friends, costs to importers, retailers and end-users. Until By the time you receive this latest issue of July, 2013 when it expired, this production was AREA magazine, the snow should have finally exempt from duty under GSP (Generalized melted, blossoms are bursting on the trees and System of Preferences), a trade program that temperatures have risen above the teens!! reduced taxes on imports of several thousand This record setting cold winter, which non-sensitive products from certain developing depressed retail floor traffic as well countries. The ORIA is working as our spirits, has thankfully with the Coalition for GSP to push passed. We fully expect store sales for its reinstatement. can now finally reflect the robust There are, of course, legitimate business we saw during Atlanta and reasons for tariffs and duty-i.e., to Las Vegas markets in January and support threatened domestic manu - the vitality we expect to see at the facturing. However, to the best of upcoming Spring High Point my knowledge, there is virtually no Market, where many our members domestic production of hand-tufted exhibit. -

SWC 1 ALL.Pdf

OF SILK, WOOL AND COTTON F INE C ARPETS AND T EXTILE A RT Specializing in Antique and Decorative carpets and textiles “I have no refuge in the world other than thy threshold; There is no protection for my head other than this doorway The work of the slave of the threshold of this Holy place” Maksud of Kashan in the year 946 H “ (1539 AD) This inscription figures in the main field of one of the most famous of all carpets, the Ardabil carpet, which covered the tomb of Shah Ismail, the founder of the Safavid Dynasty. Shah Tahmasp must have commissioned the carpet shortly after his father died in 1524, bringing the numbers of years that it took Maksud to finish this carpet to 15. The inscription above is so powerful it could have been written in some holy book, a book of faith. Instead, it is a dedication by the maker of a carpet, undoubtedly the greatest achievement of his life. Maksud might have believed that his work would be appreciated by countless generations to come, but making a great object is not the sole guarantee of appreciation. Once a great carpet is finished someone has to sell it, making the weaver and the trader two sides of the same medallion. One such side was Hussein Maktabi, my grandfather, born in 1900 in Isphahan, Persia. Coming from a long line of carpet traders, he decided to travel to Baghdad and Damascus, finally establishing himself in Beirut by 1926. Modesty prevents me from saying that he changed people’s appreciation for rugs and carpets in Lebanon, but he most certainly added to its depth. -

Licitația De Covoare Joi, 28 Februarie 2019, 19.30 Artmark, Palatul Cesianu-Racoviță

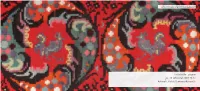

5. Atelier românesc, Covor tradițional moldovenesc, din lână, parietal, decorat cu doi cocoși și motive geometrice, prima jumătate a sec. XX Licitația de Covoare joi, 28 februarie 2019, 19.30 Artmark, Palatul Cesianu-Racoviță 120 121 3 | Covor oltenesc pentru masă, din lână, 3 Craiova, cca. 1940 2 | Covor moldovenesc din lână, produs Atelier românesc în atelier mânăstiresc, decorat cu motive bumbac; lână, d=71 cm geometrice, cca. 1920 Atelier românesc € 150 lână; bumbac, 134 x 80 cm € 200 4 | Covor oltenesc din lână, cu păsări și decor floral, atelier mănăstiresc, cca. 1975 Atelier românesc lână, 247 × 165 cm € 300 4 1 | Scoarță oltenească din lână, bogat decorată, atelier mănăstiresc, cca. 1940 Atelier românesc lână; bumbac, 146 x 89 cm € 300 122 123 7 | Covor maramureșan de rudă, din lână, 8 decorat cu motive geometrice, începutul sec. XX Atelier românesc lână, 80 × 332 cm € 500 5 5 | Covor tradițional moldovenesc, din lână, parietal, decorat cu doi cocoși și motive geometrice, prima jumătate a sec. XX 6C | Scoarță maramureșeană de rudă, din Atelier românesc lână, decorat cu motivul horei, tricolorul și lână; bumbac, 226 x 132 cm alte motive tradiționale, începutul sec. XX Atelier românesc € 1.000 lână, 372 × 78 cm € 900 8 | Scoarță maramureșeană din lână, decorat cu coarnele berbecului și motive geometrice, începutul sec. XX Atelier românesc 7 lână, 237 × 79 cm € 500 6 124 125 11 | Covor oltenesc din lână, decorat cu pristolnice, prima jumătate a sec. XX 9 | Covor muntenesc din lână, „boieresc”, Atelier românesc decorat cu motive florale, începutul sec. XX lână; bumbac, 226 x 148 cm Atelier românesc lână, 374 × 228 cm € 300 € 900 10 | Covor muntenesc, decorat cu romburi și pristolnice, mijlocul sec. -

Download the Print Catalog (PDF)

THE COLLECTOR’S EYE : Art, Antique Carpets, Decorative & Ethnographic Arts, including property from GlaxoSmithKline LLC AUCTION February 24, 2013 | 11AM EXHIBITION February 21 - 23 | 10AM-5PM Daily 4700 Wissahickon Avenue | Philadelphia, PA 19144 | 215-438-4700 | www.materialculture.com Property from the Collection of GlaxoSmithKline LLC One of the exceptional pieces brought detractors of American craft by winning to auction by GlaxoSmithKline is a the First Prize Gold Medal at the Rookwood Vase from 1900, decorated Paris Exposition Universelle in 1889. by Kitaro Shirayamandi with gorgeous Japanese artist Kitaro Shiryamandi was chrysanthemums for Rookwood invited to come to Ohio to create for the Pottery. Maria Longworth founded company in 1887, and the vase up at the Rookwood Pottery Company in auction on February 24 is a spectacular 1880 in Cincinnati, Ohio, inspired example of his artistry. In excellent by Japanese ceramics and under- condition and gleaming with golden glaze French pottery. Rookwood was and cream chrysanthemums against the first American company to gain a dark background, the hand-painted international admiration for ceramics earthenware piece–produced in 1900– from the United States, surprising measures a massive 18 by 9.5 inches. LOT 18 for designing the Diamond and Bird As is seen on some but not all of Bertoia’s chairs for the Knoll furniture company, sounding sculptures, the rods are capped which became icons of modernist with metal cylinders to accentuate the furniture, and for his “Sonambient” movement initiated by a hand or puff of sound sculpture. When he began air. Bertoia had renovated an old barn exploring tonal sculpture in 1960, he was on his estate in Bally, Pennsylvania and already well-known for his sculptures assembled 100 sounding sculptures into and installations, but his innovation in the acoustically-perfected space, where creating sculptures that generate their he recorded eleven albums featuring the own otherworldly music has come to be sonorous, sometimes haunting, tones his hallmark. -

Vol. X, No. 4 Mar. 20, 2003

View from the Fringe Newsletter of the New England Rug Society Vol. X, No. 4 March 20, 2003 www.ne-rugsociety.org April Meeting: Bertram Frauenknecht on ‘Collecting Through the Eyes of a Dealer” Our next meeting is co-sponsored by Skinner, on whose Boston premises it will take place. Our Next Meeting Details speaker will be Bertram Frauenknecht, a well known Date: Friday, April 4 rug dealer and scholar based in Munich, Germany. Time: 6 PM. PLEASE NOTE EARLY He specializes in tribal weavings with particular START! fondness for the Shahsavan. See his website at www.frauenknecht.com for information on his pub- Place: Skinner, Heritage on the Park, lications, exhibitions, and inventory. 63 Park Plaza, Boston, MA In his talk, Bertram will address the questions Pkng: Street and neighboring lots and garages of what characterizes a world-class rug and what are the criteria that collectors use to choose their acqui- and their cultures. One thing led to another, and sitions. Based on his own experiences as a collector before long he found his avocation in the field of and dealer, he will show how collections develop oriental rugs. After accumulating a small (about 20 and change as the collector becomes educated, of- pieces) collection of his own, he decided that he ten under the guidance of dealers. His slogan is: could best finance this hobby by establishing his own “Only through knowledge can you open your eyes rug gallery in Nürnberg, Germany. By 1980 he de- and see!” cided that collecting and selling were incompatible: Bertram’s academic fields of study were chem- clients always assumed that he was withholding the istry and biology, which he taught for three years.