The Australian Black Coal Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

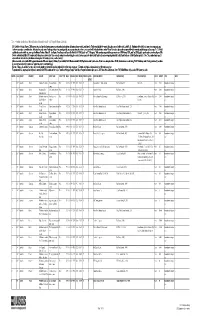

Coal Production

Coal Production A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z AA AB AC AD AE AF AG AH AI AJ AK 1 2 Summary of coal production entered on entity worksheets 3 Richard Heede 4 Climate Mitigation Services 5 22-May-13 6 7 8 1850s 1860s 1850 1851 1852 1853 1854 1855 1856 1857 1858 1859 1860 1861 1862 1863 1864 1865 1866 1867 1868 1869 1870 1871 9 Coal 10 11 12 13 1 Alpha Natural Resources, USA 14 15 2 Anglo American, UK 16 17 3 Arch Coal Company, USA 18 19 4 British Coal Corporation, UK 20 21 5 BP Coal, UK 22 23 6 BHP Billiton, Australia 24 25 7 China, Peoples Republic 26 27 8 Coal India, India 28 29 9 ConocoPhillips, USA 30 31 10 Consol Energy, USA 0.03 0.05 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.2 0 0 32 33 11 Cyprus Amax, USA 34 35 12 Czechoslovakia 36 37 13 Czech Republic + Slovakia 38 39 14 ExxonMobil, USA 40 41 15 FSU (Former Soviet Union) 42 43 16 Kazakhstan 44 45 17 Kerr-McGee Coal (Anadarko), USA 46 47 18 Kiewit Mining Group, USA 48 49 19 Luminant, USA 50 51 20 Massey Energy, USA 52 53 21 Murray Coal, USA 54 55 22 North American Coal Corp., USA 56 57 23 North Korea 58 59 24 Occidental, USA 60 61 25 Peabody Energy, USA 62 63 26 Pittsburgh & Midway Coal (Chevron) 64 65 27 Poland 66 67 28 Rio Tinto, Australia 68 69 29 RAG (Ruhrkohle AG), Germany 70 71 30 Russian Federation (not including FSU) 72 73 31 RWE, Germany 74 75 32 Sasol, South Africa 76 77 33 Singareni Collieries Company, India 78 79 34 UK Coal, UK 80 81 35 Ukraine 82 83 36 Westmoreland Coal, USA 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.3 0.3 0.4 84 85 37 Xstrata, Switzerland -

Cerrejón Coal Mine Colombia

Cerrejón coal mine Colombia Sectors: Coal Mining Active This profile is actively maintained Send feedback on this profile By: BankTrack Created before Nov 2016 Last update: May 19 2021 Contact: Alex Scrivener, Policy Officer, Global Justice Now Project website Status Planning Design Agreement Construction Operation Closure Decommission Sectors Coal Mining Location Status Planning Design Agreement Construction Operation Closure Decommission Website http://www.cerrejon.com/site/ About Cerrejón coal mine The Cerrejón coal mine in La Guajira, Colombia, is the largest in Latin America and one of the largest in the world. Its steady expansion since its founding in 1976 has led to the destruction of whole villages populated by local indigenous and Afro-Colombian people. The extracted coal is almost exclusively for export to rich countries with local people seeing few benefits. The mine is owned by three giant UK-listed mining companies: BHP Billiton, Anglo American and Glencore. All of which receive billions of pounds in finance from UK banks and pension funds. Roche, Chancleta, Tamaquitos, Manantial, Tabaco, Palmarito, El Descanso, Caracoli, Zarahita, Patilla. These are the names of just some of the communities that have been devastated or simply wiped off the map by the Cerrejón mining project. Latest developments Anglo American to exit from Cerrejon shareholding, BHP Group to follow Feb 25 2021 Glencore leaving, passing mining contracts to Republic of Colombia Feb 4 2021 Impacts Social and human rights impacts While the Cerrejón mining company's promotional material gives the impression that it is helping the displaced communities, the reality is that the mining company has used underhand tactics to buy off individuals and sow internal division within the communities. -

A Last Chance for Coal Making Carbon Capture and Storage a Reality

a last chance for coal making carbon capture and storage a reality foreword by Rt Hon Margaret Beckett MP Jon Gibbins & Hannah Chalmers David Hawkins Graeme Sweeney Jules Kortenhorst Linda McAvan MEP Alain Berger Ruud Lubbers Frances O’Grady Mike Farley Matthew Lockwood Ben Caldecott & Thomas Sweetman Keith Allott Karla Hill & Tim Malloch Sheryl Carter compiled and edited by Chris Littlecott This publication is part of Green Alliance’s climate change theme (www.green-alliance.org.uk/climatechange), which is kindly supported by Shell. Green Alliance’s work on the financing of CCS demonstration projects is kindly supported by BP. The views expressed in this publication remain those of the individual authors alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of Green Alliance or its sponsors. Acknowledgments Many thanks to all those who have advised and assisted in the preparation of this publication, particularly Rebecca Collyer, Mark Johnston and Jesse Scott. Special thanks are due to Catherine Beswick, Karen Crane, Maureen Murphy, Rebekah Phillips and Faye Scott for their invaluable editorial input. a last chance for coal making carbon capture and storage a reality Edited by Chris Littlecott ISBN 978-1-905869-15-2 © Green Alliance 2008 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Green Alliance. Within the UK, exceptions are allowed in respect of any fair dealing for the purposes of private research or study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of the licenses issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. -

Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254)

Table1.—Attribute data for the map "Mineral Facilities of Asia and the Pacific," 2007 (Open-File Report 2010-1254). [The United States Geological Survey (USGS) surveys international mineral industries to generate statistics on the global production, distribution, and resources of industrial minerals. This directory highlights the economically significant mineral facilities of Asia and the Pacific. Distribution of these facilities is shown on the accompanying map. Each record represents one commodity and one facility type for a single location. Facility types include mines, oil and gas fields, and processing plants such as refineries, smelters, and mills. Facility identification numbers (“Position”) are ordered alphabetically by country, followed by commodity, and then by capacity (descending). The “Year” field establishes the year for which the data were reported in Minerals Yearbook, Volume III – Area Reports: Mineral Industries of Asia and the Pacific. In the “DMS Latitiude” and “DMS Longitude” fields, coordinates are provided in degree-minute-second (DMS) format; “DD Latitude” and “DD Longitude” provide coordinates in decimal degrees (DD). Data were converted from DMS to DD. Coordinates reflect the most precise data available. Where necessary, coordinates are estimated using the nearest city or other administrative district.“Status” indicates the most recent operating status of the facility. Closed facilities are excluded from this report. In the “Notes” field, combined annual capacity represents the total of more facilities, plus additional -

The Case for Mine Energy – Unlocking Deployment at Scale in the UK a Mine Energy White Paper

The Case for Mine Energy – unlocking deployment at scale in the UK A mine energy white paper @northeastlep northeastlep.co.uk @northeastlep northeastlep.co.uk Foreword At the heart of this Government’s agenda are three key priorities: the development of new and innovative sources of employment and economic growth, rapid decarbonisation of our society, and levelling up - reducing the inequalities between diferent parts of the UK. I’m therefore delighted to be able to ofer my support to this report, which, perhaps uniquely, involves an approach which has the potential to address all three of these priorities. Mine energy, the use of the geothermally heated water in abandoned coal mines, is not a new technology, but it is one with the potential to deliver thousands of jobs. One quarter of the UK’s homes and businesses are sited on former coalfields. The Coal Authority estimates that there is an estimated 2.2 GWh of heat available – enough to heat all of these homes and businesses, and drive economic growth in some of the most disadvantaged communities in our country. Indeed, this report demonstrates that if we only implement the 42 projects currently on the Coal Authority’s books, we will deliver almost 4,500 direct jobs and a further 9-11,000 in the supply chain, at the same time saving 90,000 tonnes of carbon. The report also identifies a number of issues which need to be addressed to take full advantage of this opportunity; with investment, intelligence, supply chain development, skills and technical support all needing attention. -

Draft Energy Bill: Pre–Legislative Scrutiny

House of Commons Energy and Climate Change Committee Draft Energy Bill: Pre–legislative Scrutiny First Report of Session 2012-13 Volume III Additional written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 24 May, 12, 19 and 26 June, 3 July, and 10 July 2012 Published on Monday 23 July 2012 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited The Energy and Climate Change Committee The Energy and Climate Change Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department of Energy and Climate Change and associated public bodies. Current membership Mr Tim Yeo MP (Conservative, South Suffolk) (Chair) Dan Byles MP (Conservative, North Warwickshire) Barry Gardiner MP (Labour, Brent North) Ian Lavery MP (Labour, Wansbeck) Dr Phillip Lee MP (Conservative, Bracknell) Albert Owen MP (Labour, Ynys Môn) Christopher Pincher MP (Conservative, Tamworth) John Robertson MP (Labour, Glasgow North West) Laura Sandys MP (Conservative, South Thanet) Sir Robert Smith MP (Liberal Democrat, West Aberdeenshire and Kincardine) Dr Alan Whitehead MP (Labour, Southampton Test) The following members were also members of the committee during the parliament: Gemma Doyle MP (Labour/Co-operative, West Dunbartonshire) Tom Greatrex MP (Labour, Rutherglen and Hamilton West) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

United Kingdom – Extensive Potential and a Positive Outlook by Paul Lusty, British Geological Survey Introduction in Relation

United Kingdom – extensive potential and a positive outlook By Paul Lusty, British Geological Survey Introduction In relation to its size the United Kingdom (UK) is remarkably well-endowed with mineral resources as a result of its complex geological history. Their extraction and use have played an important role in the development of the UK economy over many years and minerals are currently worked at some 2100 mine and quarry sites. Production is now largely confined to construction minerals, primarily aggregates, energy minerals and industrial minerals including salt, potash, kaolin and fluorspar, although renewed interest in metals is an important development in recent years. With surging global demand for minerals the UK is seen by explorers as an attractive location to develop projects. With low political risk and excellent infrastructure a survey conducted by Resources Stocks (2009) ranked the UK twelfth in a global assessment of countries’ risk profiles for resource sector investment. Northern Ireland is notable in terms of the extensive licence coverage for gold and base metal exploration and in having the UK’s only operational metalliferous mine. The most advanced projects elsewhere include the Hemerdon tin-tungsten deposit in Devon, the South Crofty tin deposit in Cornwall and the Cononish gold deposit in central Scotland. UK coal has seen a resurgence during the last three years driven largely by higher global prices, making it more competitive with imports. Coal is also viewed as having a key role in the future UK energy mix. This has led to greater investment in UK operations resulting in increased numbers of new opencast sites commencing production and more permit applications for further sites. -

Articles on Mining History from Mining and History

North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers Nicholas Wood Memorial Library Articles on mining history from mining and history journals: a list May 2017 These are mainly from the Transactions of the professional mining institutions and from economic and other history journals and are grouped in broad topics as well as in a complete list. Some references may appear in more than one grouping. They all relate to the UK. It is a work in progress and further articles will be added from time to time. Publications from mining history societies are mostly not included, but an online index at http://www.sat.dundee.ac.uk/bin/pdmhsearch covers articles from British Speleological Association 1947-73 Northern Cave and Mine Research Society 1961-74 Northern Mine Research Society 1975- (British Mining) Peak District Mines Historical Society 1959- The complete list of articles is followed by the subject groupings: General mining history Labour: miners; productivity Legislation Metalliferous and other non-coal mining Mining technologies Professional institutions; education Regional studies Safety and inspection Safety lamps Items marked X are not in the Institute Library. Page 1 Author Title Journal vol date pages Adam, T.W. The history of the Midland Institute of Mining Engineers Transactions – Institution of 106 1946-7 166-175 Mining Engineers Adam, T.W. & A historical review of the Midland Institute of Mining Transactions – Institution of 117 1957-8 606-620 Statham, I.C.F. Engineers Mining Engineers Adams, M Humphry Davy and the murder lamp History today 55 2005 207-208 X Almond, J.K. British technical education for mining: an historical survey to Transactions - Institution of 84 1975 A60-A70 1920. -

Coal Introduction Geology of Coal Formation of Coal

COAL INTRODUCTION STATE OF OHIO Ted Strickland, Governor Coal is one of Ohio’s most valuable mineral resources DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES and the nation’s most abundant fossil fuel. More than 3.7 bil- Sean D. Logan, Director lion tons of Ohio coal has been mined since 1800, and recent DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY fi gures indicate that Ohio is the 3rd largest coal-consuming Larry Wickstrom, Chief state in the nation, consuming about 62 million tons per year. Ohio ranks 13th in the nation in coal production, and 7th in terms of demonstrated coal reserves with approximately 23.3 billion short tons, or 4.7% of the nation’s total coal reserves. (“Demonstrated Coal Reserve” is a term used to identify the part of the total resource that is potentially mineable when considering economic, legal, and engineering constraints). At present production levels, Ohio has more than 500 years worth of potentially mineable coal remaining. GEOLOGY OF COAL Th e coal-bearing rocks of Ohio were deposited during the Pennsylvanian and Permian Periods, approximately 320 to 245 million years ago. During Pennsylvanian time, or the great Coal Age, a shallow sea covered central Ohio. A series of river deltas extended into this sea carrying sediments that eroded from the ancestral Appalachian Mountains and fl owed northwest into the deltas. Extensive freshwater and brackish-water peat-forming COAL ecosystems formed in these low-lying coastal and near-coastal deltas, which were similar to those of the current Mississippi and Amazon Rivers. Th ese peat swamps remained undisturbed for thousands of years. -

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2012

Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics 2012 Production team: Iain MacLeay Kevin Harris Anwar Annut and chapter authors A National Statistics publication London: TSO © Crown Copyright 2012 All rights reserved First published 2012 ISBN 9780115155284 Digest of United Kingdom Energy Statistics Enquiries about statistics in this publication should be made to the contact named at the end of the relevant chapter. Brief extracts from this publication may be reproduced provided that the source is fully acknowledged. General enquiries about the publication, and proposals for reproduction of larger extracts, should be addressed to Kevin Harris, at the address given in paragraph XXIX of the Introduction. The Department of Energy and Climate Change reserves the right to revise or discontinue the text or any table contained in this Digest without prior notice. About TSO's Standing Order Service The Standing Order Service, open to all TSO account holders, allows customers to automatically receive the publications they require in a specified subject area, thereby saving them the time, trouble and expense of placing individual orders, also without handling charges normally incurred when placing ad-hoc orders. Customers may choose from over 4,000 classifications arranged in 250 sub groups under 30 major subject areas. These classifications enable customers to choose from a wide variety of subjects, those publications that are of special interest to them. This is a particularly valuable service for the specialist library or research body. All publications will be dispatched immediately after publication date. Write to TSO, Standing Order Department, PO Box 29, St Crispins, Duke Street, Norwich, NR3 1GN, quoting reference 12.01.013. -

The Coal Mining Heritage of Lafayette

The Coal Mining Heritage of Lafayette From the late I 880s until the I 930s, Lafayette was a major coal town. Read the history of the coal mining era, examine the location of coal mines within the Lafayette area, and enjoy historic photos of the Waneka Lake Power Plant and the Simpson Mine with the attached Coal Mines of the Lafaveti’e Area brochure. This brochure was created by the Lafayette Historic Preservation board, and it highlights the fascinating Coal Mining Heritage of Lafayette. oft/ic — • Coal Mines Lafayette Area page 1 • Coal Mines of the Lafayette Area - page 2 • Coal Mines f the Lfa)’ette Area — map ____________________________ Historic Preservation Board, City of Lafayette, Colorado The social legacy. The social legacy of mining is equally important to contemporary Lafayette The mines required far more labor than was available locally and quickly attracted experienced miners and laborers from Europe and other parts of the U.S. The result was a community comprised of many ethnic groups, including Welsh, English. Scottish, Irish, central European, Hispanic, Italian, and Swedish workers and their families. Local farmers and ranchers also shared in the coal boom and worked as miners in the winter when coal production was high and agricultural work slow. A sense of this ethnic diversity can be gained by walking through the Lafayette cemetery at Baseline and 111th Street. The variety of family names gives a sense of the many nationalities that have contributed to Lafayette’s history. Although the mining life was hard, families were fun-loving and many social activities centered around schools and churches. -

2008 Abstract Booklet

TWENTY - FIFTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL PITTSBURGH COAL CONFERENCE COAL - ENERGY, ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT ABSTRACTS BOOKLET September 29 - October 2, 2008 The Westin Convention Center Pittsburgh, PA USA The Westin Hotel and Convention Center Hosted By: University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering A NOTE TO THE READER This Abstracts Booklet is prepared solely as a convenient reference for the Conference participants. Abstracts are arranged in a numerical order of the oral and poster sessions as published in the Final Conference Program. In order to facilitate the task for the reader to locate a specific abstract in a given session, each paper is given two numbers: the first designates the session number and the second represents the paper number in that session. For example, Paper No. 25-1 is the first paper to be presented in the Oral Session #25. Similarly, Paper No. P3-1 is the first paper to appear in the Poster Session #3. It should be cautioned that this Abstracts Booklet is prepared based on the original abstract that was submitted, unless the author noted an abstract change. The contents of the Booklet do not reflect late changes made by the authors for their presentations at the Conference. The reader should consult the Final Conference Program for any such changes. Furthermore, updated and detailed full manuscripts are published in the CD-ROM Conference Proceedings will be sent to all registered participants following the Conference. On behalf of the Twenty-Fifth Annual International Pittsburgh Coal Conference, we wish to express our sincere appreciation to Ms. Heidi M. Aufdenkamp, Mr.