The New Mother”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Microfilms International 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 USA St

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand marking: or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Big Blast & the Party Masters

BIG BLAST & THE PARTY MASTERS 2018 Song List ● Aretha Franklin - Freeway of Love, Dr. Feelgood, Rock Steady, Chain of Fools, Respect, Hello CURRENT HITS Sunshine, Baby I Love You ● Average White Band - Pick Up the Pieces ● B-52's - Love Shack - KB & Valerie+A48 ● Beatles - I Want to Hold Your Hand, All You Need ● 5 Seconds of Summer - She Looks So Perfect is Love, Come Together, Birthday, In My Life, I ● Ariana Grande - Problem (feat. Iggy Azalea), Will Break Free ● Beyoncé & Destiny's Child - Crazy in Love, Déjà ● Aviici - Wake Me Up Vu, Survivor, Halo, Love On Top, Irreplaceable, ● Bruno Mars - Treasure, Locked Out of Heaven Single Ladies(Put a Ring On it) ● Capital Cities - Safe and Sound ● Black Eyed Peas - Let's Get it Started, Boom ● Ed Sheeran - Sing(feat. Pharrell Williams), Boom Pow, Hey Mama, Imma Be, I Gotta Feeling Thinking Out Loud ● The Bee Gees - Stayin' Alive, Emotions, How Deep ● Ellie Goulding - Burn Is You Love ● Fall Out Boy - Centuries ● Bill Withers - Use Me, Lovely Day ● J Lo - Dance Again (feat. Pitbull), On the Floor ● The Blues Brothers - Everybody Needs ● John Legend - All of Me Somebody, Minnie the Moocher, Jailhouse Rock, ● Iggy Azalea - I'm So Fancy Sweet Home Chicago, Gimme Some Lovin' ● Jessie J - Bang Bang(Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj) ● Bobby Brown - My Prerogative ● Justin Timberlake - Suit and Tie ● Brass Construction - L-O-V-E - U ● Lil' Jon Z & DJ Snake - Turn Down for What ● The Brothers Johnson - Stomp! ● Lorde - Royals ● Brittany Spears - Slave 4 U, Till the World Ends, ● Macklemore and Ryan Lewis - Can't Hold Us Hit Me Baby One More Time ● Maroon 5 - Sugar, Animals ● Bruno Mars - Just the Way You Are ● Mark Ronson - Uptown Funk (feat. -

CATHOLIC School and Sodality HYMNAL

FROM THE LIBRARY OF REV. LOUIS FITZGERALD BENSON, D. D. BEQUEATHED BY HIM TO THE LIBRARY OF PRINCETON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY PWiaios 1 "2 * MAR 28 1934 CATHQL^oG;CAL , School and Sodality HYMNAL FIRST EDITION t PHILADELPHIA \ Geo. W. Gibbons, Publisher 906 Filbert Street 1900 Copyright, 1900. INDEX GOD. Coine, sound His praise abroad 66 Fading twilight tints are weaving 81 Father, before Thy footstool kneeling. 84 Holy God, we praise Thy name 128 King of Ages, King victorious 151 Laudate Dominum 155 Lord, Thou wilt hear the prayer 167 My God, I love Thee not because 185 My soul, Thy groat Creator praise 189 My God, my life, my love 190 Nearer, my God, to Thee 194 Oh! Come, loud anthems let us sine. .254 Strike the harp in praise of God! 297 The earth, O Lord, rejoices 316 The wearied dove now trembling flies. .328 We praise Thee. O God. etc 362 THE HOLY GHOST. Come. Holy Ghost. Creator blest 61 Come, Holy Ghost, send down, etc 62 Vein, Creator spiritus 350 Vein, Sancte spiritus 352 PENTECOST. See the Paraclete Descending 286 CHRISTMAS. Adeste fideles 2 Angels we have heard on high 16 At last Thou art come 24 iii Christ was bom on Chrismtas Day.... 54 Come, let us gather round the crib." 62 Come. O divine Messiah 65 Earthly friends will change and falter. 79 Hark! the herald angels sing 114 He came from His high throne, etc 116 Holy night, peaceful night 130 Like the dawning of the morning 160 Merry Christmas, Merry Christmas. .. .175 holy night! the stars, etc 212 < )h ! sing a joyous carol 257 See! Amid the winter's snow 284 See, the dawn from Heaven is breaking.285 Silent night, sacred night 287 The lights are bright in Bethlehem town..318 The snow lay on the ground, etc 321 We sing with the angels 363 We three kings from Orient are. -

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : the Lyrics Book - 1 SOMMAIRE

Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 1 SOMMAIRE P.03 P.21 P.51 P.06 P.26 P.56 P.09 P.28 P.59 P.10 P.35 P.66 P.14 P.40 P.74 P.15 P.42 P.17 P.47 Madonna - 1982 - 2009 : The Lyrics Book - www.madonnalex.net 2 ‘Cause you got the best of me Chorus: Borderline feels like I’m going to lose my mind You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline (repeat chorus again) Keep on pushing me baby Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline Something in your eyes is makin’ such a fool of me When you hold me in your arms you love me till I just can’t see But then you let me down, when I look around, baby you just can’t be found Stop driving me away, I just wanna stay, There’s something I just got to say Just try to understand, I’ve given all I can, ‘Cause you got the best of me (chorus) Keep on pushing me baby MADONNA / Don’t you know you drive me crazy You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline THE FIRST ALBUM Look what your love has done to me 1982 Come on baby set me free You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline You cause me so much pain, I think I’m going insane What does it take to make you see? LUCKY STAR You just keep on pushing my love over the borderline written by Madonna 5:38 You must be my Lucky Star ‘Cause you shine on me wherever you are I just think of you and I start to glow BURNING UP And I need your light written by Madonna 3:45 Don’t put me off ‘cause I’m on fire And baby you know And I can’t quench my desire Don’t you know that I’m burning -

CHARACTERS of the PLAY Medea, Daughter of Aiêtês, King of Colchis. Jason, Chief of the Argonauts

MEDEA CHARACTERS OF THE PLAY Medea, daughter of Aiêtês, King of Colchis. Jason, chief of the Argonauts; nephew of Pelias, King of Iôlcos in Thessaly. Creon, ruler of Corinth. Aegeus, King of Athens. Nurse of Medea. Two Children of Jason and Medea. Attendant on the children. A Messenger. Chorus of Corinthian Women, with their Leader. Soldiers and Attendants. The scene is laid in Corinth. The play was first acted when Pythodôrus was Archon, Olympiad 87, year 1 (B.C. 431). Euphorion was first, Sophocles second, Euripides third, with Medea, Philoctêtes, Dictys, and the Harvesters, a Satyr-play. The Scene represents the front of Medea's House in Corinth. A road to the right leads towards the royal castle, one on the left to the harbor. The Nurse is discovered alone. Nurse. If only the gods barred the Argo from winning the golden fleece. Then my princess, Medea, would have never traveled to Iolcus with her love Jason. Then she wouldn’t have deceived the daughters of King Pelias to kill their father. Causing her and her family to flee to Corinth. But now, Jason and Medea’s love is poisoned. Jason has spurned my princess and his own sons, for a crown. He has married the daughter of Creon. And Creon is the king of Corinth. Medea cries for her family and her home that she destroyed in Colohis. What scares me the most is that she looks at her children with hate. I know that woman. She has some scheme. (Children playing noises) Here come her children, happy and free from their mother’s pain. -

Comedia De La Fuerza De La Costumbre the Force of Habit Por Don Guillén De Castro a Comedy by Don Guillén De Castro

Comedia de La fuerza de la costumbre The Force of Habit por don Guillén de Castro A comedy by Don Guillén de Castro PERSONAS CHARACTERS DOÑA COSTANZA, madre de FÉLIX e HIPÓLITA COSTANZA, mother to FÉLIX and HIPÓLITA DON FÉLIX, 20 FÉLIX, 20 DON PEDRO DE MONCADA, esposo de COSTANZA, padre PEDRO, COSTANZA'S long-lost husband, father to FÉLIX de FÉLIX e HIPÓLITA AND HIPÓLITA DOÑA HIPÓLITA, 20 HIPÓLITA, 20 UN VIEJO, AYO de DON FÉLIX FÉLIX'S TUTOR (AYO) GALVÁN, locayo GALVÁN, servant INÉS, criada de LEONOR INÉS, LEONOR'S servant DOÑA LEONOR, ama a FÉLIX LEONOR, 20'S, loves FÉLIX DON LUIS, galán de HIPÓLITA, hermano de LEONOR LUIS, 20'S, suitor to HIPÓLITA, LEONOR'S brother OTAVIO, galán de LEONOR OTAVIO, suitor to LEONOR MARCELO, galán de HIPÓLITA MARCELO, suitor to HIPÓLITA MAESTRO de armas FENCING MASTER ALGUACIL BAILIFF CAPITÁN CAPTAIN 1 JORNADA PRIMERA ACT ONE Salen DOÑA COSTANZA y DON FÉLIX, en hábito largo de Enter DOÑA COSTANZA and DON FÉLIX. FÉLIX wears the estudiante long habit of a student FÉLIX ¿Qué novedades son estas, FÉLIX What novelties are these, mi señora? ¿Qué mudanzas? my lady? What changes? ¿Del hábito de sayal, From a sackcloth robe, monjil pardo, tocas largas, a nun’s brown habit, long wimples, al enrizado cabello, and a rosary, trenzas de oro, entera saya; to curled hair, del rosario a la cadena, braids of gold, a full skirt, de los lutos a las galas? and a fine chain? Ayer desnudas paredes, From mourning to celebration? de tristeza, apenas blancas, Yesterday, bare walls, y hoy de brocados y sedas sad and dull, tan compuestas y entoldadas. -

Playing Beattie Bow Music Credits

Music Garry McDonald & Laurie Stone Music Mixer Peter Smith 'Heart to Heart' Music & Lyrics by McDonald & Stone Sung by Karen Boddington (Cast) Singer Perri Hamilton Highland Piper Rob George Pianist (Brothel) Pat Wilson The film opens with a children's choir singing/chanting a rhyme: Oh mother, oh mother, what's that, what's that? A dog at the door, a dog at the door. Oh mother, oh mother, what's that, what's that? The wind in the chimney, that's all. Oh mother, oh mother, what's that, what's that? The cow in the bye, the horse in the stall Oh mother, oh mother, what's that, what's that? It's Beatie Bow, risen from the dead. There is an 1980s style pop song running over the end titles, with percussive and synth features typical of the times. Singer Karen Boddington was a well known session singer of the time, and by dint of her vocal duet with NZ pop singer Mark Williams performing the original theme tune for the long-running TV soap, Home and Away, has a brief wiki listing here. Lyrics for the song: Words won't tell me what's in your heart I can't believe what you say. Eyes can't see what thoughts you hide You feel so far away Compliments that you give to me Don't reveal that much it seems All the love that you offer me Only fuels my silent scream But when you're near me I hear my heart Beating out the words so rare Something changes each time we touch The hesitation disappears Heart to heart Face to face Heart to heart to heart Heart to heart Face to face Heart to heart to heart Lies aren't worth the breath they take Don't fool the lucky -

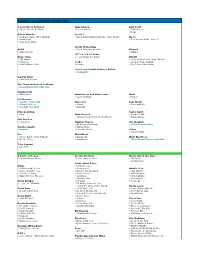

Recordings by Women Table of Contents

'• ••':.•.• %*__*& -• '*r-f ":# fc** Si* o. •_ V -;r>"".y:'>^. f/i Anniversary Editi Recordings By Women table of contents Ordering Information 2 Reggae * Calypso 44 Order Blank 3 Rock 45 About Ladyslipper 4 Punk * NewWave 47 Musical Month Club 5 Soul * R&B * Rap * Dance 49 Donor Discount Club 5 Gospel 50 Gift Order Blank 6 Country 50 Gift Certificates 6 Folk * Traditional 52 Free Gifts 7 Blues 58 Be A Slipper Supporter 7 Jazz ; 60 Ladyslipper Especially Recommends 8 Classical 62 Women's Spirituality * New Age 9 Spoken 64 Recovery 22 Children's 65 Women's Music * Feminist Music 23 "Mehn's Music". 70 Comedy 35 Videos 71 Holiday 35 Kids'Videos 75 International: African 37 Songbooks, Books, Posters 76 Arabic * Middle Eastern 38 Calendars, Cards, T-shirts, Grab-bag 77 Asian 39 Jewelry 78 European 40 Ladyslipper Mailing List 79 Latin American 40 Ladyslipper's Top 40 79 Native American 42 Resources 80 Jewish 43 Readers' Comments 86 Artist Index 86 MAIL: Ladyslipper, PO Box 3124-R, Durham, NC 27715 ORDERS: 800-634-6044 M-F 9-6 INQUIRIES: 919-683-1570 M-F 9-6 ordering information FAX: 919-682-5601 Anytime! PAYMENT: Orders can be prepaid or charged (we BACK ORDERS AND ALTERNATIVES: If we are tem CATALOG EXPIRATION AND PRICES: We will honor don't bill or ship C.O.D. except to stores, libraries and porarily out of stock on a title, we will automatically prices in this catalog (except in cases of dramatic schools). Make check or money order payable to back-order it unless you include alternatives (should increase) until September. -

American Indian Stories

AMERICAN INDIAN STORIES [Frontispiece] ZITKALA-SA (Gertrude Bonnin) A Dakota Sioux Indian [Title Page] American Indian Stories BY ZITKALA-SA (Gertrude Bonnin ) Dakota Sioux Indian Lecturer; Author of "Old Indian Legends," "Americanize the First American," and other stories; Member of the Woman's National Foundation, League of American Pen-Women, and the Washington Salon "There is no great; there is no small; in the mind that causeth all " Washington Hayworth Publishing House 1921 2 [Page] [Page] CONTENTS PAGE Impressions of an Indian Childhood 7 The School Days of an Indian Girl 47 An Indian Teacher Among Indians 81 The Great Spirit 101 The Soft-Hearted Sioux 109 The Trial Path 127 A Warrior's Daughter 137 A Dream of Her Grandfather 155 The Widespread Enigma of Blue-Star Woman 159 America's Indian Problem 185 [Page] Impressions of an Indian Childhood I MY MOTHER A WIGWAM of weather-stained canvas stood at the base of some irregularly ascending hills. A footpath wound its way gently down the sloping land till it reached the broad river bottom; creeping through the long swamp grasses that bent over it on either side, it came out on the edge of the Missouri. Here, morning, noon, and evening, my mother came to draw water from the muddy stream for our household use. Always, when my mother started for the river, I stopped my play to run along with her. She was only of medium height. Often she was sad and silent, at which times her full arched lips were compressed into hard and bitter lines, and shadows fell under her black eyes. -

The Five Star Band Song List

CURRENT & LEGENDARY DANCE HITS! 5 Seconds of Summer Iggy Azalea Katy Perry › She Looks So Perfect ›I'm So Fancy › Dark Horse › Roar Ariana Grande Jessie J › Problem (feat. Iggy Azalea) › Bang Bang(Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj) Ne-Yo › Break Free › She Knows (feat. Juicy J) › One Last Time Justin Timberlake Aviici › Can't Stop the Feeling Pharrell › Wake Me Up › Happy Lil' Jon Z & DJ Snake Bruno Mars > Turn Down for What Pitbull › 24K Magic › Time of Our Lives (feat. Ne-Yo) › Finesse Lorde › Timber (feat. Ke$ha) › That's What I Like › Royals › Don't Stop This Party Luis Fonsi/Daddy Yankee/ Bieber › Despacito Capital Cities › Safe and Sound The Chainsmokers & Coldplay › Something Just Like This Charlie Puth › Attention Macklemore and Ryan Lewis Rude › Can't Hold Us › Magic! Ed Sheeran › Castle on the Hill Maroon 5 Sam Smith › Shape of You › Sugar › Stay With Me › Thinking Out Loud › Animals Ellie Goulding Taylor Swift › Burn Mark Ronson › Shake It Off › Uptown Funk (feat. Bruno Mars) › Blank Space Fall Out Boy › Centuries Meghan Trainor The Weeknd › All About That Bass › Can't Feel My Face Camila Cabello › Blank Space › Havava › Lips Are Movin Usher › I Don’t' Mind J Lo Nicki Minaj › Dance Again (feat. Pitbull) >Anaconda Walk The Moon › On the Floor >Starships › Shut Up and Dance with Me John Legend › All of Me A Taste of Honey Doobie Brothers Morris Day & the Time › Boogie Oogie Oogie › Long Train Runnin' › The Bird › Jungle Love Earth, Wind & Fire Adele › Let's Groove › Rolling in the Deep › September Natalie Cole › Someone Like You › Boogie -

Amahl and the Night Visitors by Gian-Carlo Menotti

Amahl and the Night Visitors by Gian-Carlo Menotti Cast Amahl (boy soprano) Amahl’s Mother (soprano or mezzo-soprano) King Kaspar (tenor) King Melchior (baritone) King Balthazar (bass) The Page (bass) The Shepherds ONLY ACT MOTHER (storming out of the house) Amahl sits outside a poor shack of a house, How long must I shout gazing earnestly at the sky. to make you obey? MOTHER AMAHL (calling from inside the house) I’m sorry, Mother. Amahl! Amahl! MOTHER AMAHL Hurry in! It’s time to go to bed. (replying absently) Oh! AMAHL (pleading with his mother) MOTHER But Mother – (again, coming from somewhere inside) let me stay a little longer. Time to go to bed. MOTHER AMAHL The wind is cold. (answering) Coming... AMAHL (continuing to gaze at the stars above him) But my cloak is warm; let me stay a little longer! MOTHER (her voice a bit terser) MOTHER Amahl! The night is dark. AMAHL AMAHL (again, the boy replies) But the sky is light, Coming... let me stay a little longer! (but otherwise he seems not to have heard) MOTHER The time is late. 2 AMAHL Come outside and let me show you. But the moon hasn’t risen yet, See for yourself... see for yourself. let me stay a little... MOTHER MOTHER (reprimanding Amahl) (cutting him off curtly) Stop bothering me! There won’t be any moon tonight. Why should I believe you? But there will be a weeping child very soon, You come with a new one every day! if he doesn’t hurry up and obey his mother. -

Old Time Music in Central Pennsylvania By

4 Old Time Music in Central Pennsylvania By Carl R. Catherman Old time music is generally thought of as music played on acoustic stringed instruments, particularly fiddle1, banjo and guitar, which were most often used by string bands in the Appalachian region. In addition to those three Jim and Jane and the Western Vagabonds. Rawhide (seated) and Tumbleweed (standing) 2nd from the left, 1938. (author's collection) main instruments various bands used the mandolin, upright bass, washtub bass, ukulele, harmonica, autoharp, mountain dulcimer (an American invention), jug, pump organ and anything else that might contribute useful sounds. The Old- Time Herald, a quality magazine published in Durham, North Carolina since 1988, focuses on music with roots in Appalachia, including Afro-American and 1 The word fiddle is used universally to refer to the violin by old time and bluegrass musicians and also by some musicians in all genres. 5 Cherokee musicians, but also expands its coverage to include regional styles such as Cajun, Norteño, Norwegian-American Hardanger fiddle players from the Upper Midwest, early cowboy singers and others. The concertina or accordion are used in at least two of these regional styles. The fiddle has been in America almost from the time of the earliest European settlements, brought here mostly by Irish or Scottish immigrants to the United States and by the French to Canada. Often called the devil’s box, it was used primarily to provide music for dancing. The modern banjo is an American adaptation of gourd instruments played by African slaves. It first became popular among Whites in the 1830s.