Continental Speciation in the Tropics: Contrasting Biogeographic Patterns of Divergence in the Uroplatus Leaf-Tailed Gecko Radiation of Madagascar C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blumgart Et Al 2017- Herpetological Survey Nosy Komba

Journal of Natural History ISSN: 0022-2933 (Print) 1464-5262 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnah20 Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar Dan Blumgart, Julia Dolhem & Christopher J. Raxworthy To cite this article: Dan Blumgart, Julia Dolhem & Christopher J. Raxworthy (2017): Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar, Journal of Natural History, DOI: 10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 Published online: 28 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 23 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tnah20 Download by: [BBSRC] Date: 21 March 2017, At: 02:56 JOURNAL OF NATURAL HISTORY, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar Dan Blumgart a, Julia Dolhema and Christopher J. Raxworthyb aMadagascar Research and Conservation Institute, BP 270, Hellville, Nosy Be, Madagascar; bDivision of Vertebrate Zoology, American, Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY A six month herpetological survey was undertaken between March Received 16 August 2016 and September 2015 on Nosy Komba, an island off of the north- Accepted 17 January 2017 west coast of mainland Madagascar which has undergone con- KEYWORDS fi siderable anthropogenic modi cation. A total of 14 species were Herpetofauna; conservation; found that have not been previously recorded on Nosy Komba, Madagascar; Nosy Komba; bringing the total island diversity to 52 (41 reptiles and 11 frogs). -

PRAVILNIK O PREKOGRANIĈNOM PROMETU I TRGOVINI ZAŠTIĆENIM VRSTAMA ("Sl

PRAVILNIK O PREKOGRANIĈNOM PROMETU I TRGOVINI ZAŠTIĆENIM VRSTAMA ("Sl. glasnik RS", br. 99/2009 i 6/2014) I OSNOVNE ODREDBE Ĉlan 1 Ovim pravilnikom propisuju se: uslovi pod kojima se obavlja uvoz, izvoz, unos, iznos ili tranzit, trgovina i uzgoj ugroţenih i zaštićenih biljnih i ţivotinjskih divljih vrsta (u daljem tekstu: zaštićene vrste), njihovih delova i derivata; izdavanje dozvola i drugih akata (potvrde, sertifikati, mišljenja); dokumentacija koja se podnosi uz zahtev za izdavanje dozvola, sadrţina i izgled dozvole; spiskovi vrsta, njihovih delova i derivata koji podleţu izdavanju dozvola, odnosno drugih akata; vrste, njihovi delovi i derivati ĉiji je uvoz odnosno izvoz zabranjen, ograniĉen ili obustavljen; izuzeci od izdavanja dozvole; naĉin obeleţavanja ţivotinja ili pošiljki; naĉin sprovoĊenja nadzora i voĊenja evidencije i izrada izveštaja. Ĉlan 2 Izrazi upotrebljeni u ovom pravilniku imaju sledeće znaĉenje: 1) datum sticanja je datum kada je primerak uzet iz prirode, roĊen u zatoĉeništvu ili veštaĉki razmnoţen, ili ukoliko takav datum ne moţe biti dokazan, sledeći datum kojim se dokazuje prvo posedovanje primeraka; 2) deo je svaki deo ţivotinje, biljke ili gljive, nezavisno od toga da li je u sveţem, sirovom, osušenom ili preraĊenom stanju; 3) derivat je svaki preraĊeni deo ţivotinje, biljke, gljive ili telesna teĉnost. Derivati većinom nisu prepoznatljivi deo primerka od kojeg potiĉu; 4) država porekla je drţava u kojoj je primerak uzet iz prirode, roĊen i uzgojen u zatoĉeništvu ili veštaĉki razmnoţen; 5) druga generacija potomaka -

Cop13 Analyses Cover 29 Jul 04.Qxd

IUCN/TRAFFIC Analyses of the Proposals to Amend the CITES Appendices at the 13th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties Bangkok, Thailand 2-14 October 2004 Prepared by IUCN Species Survival Commission and TRAFFIC Production of the 2004 IUCN/TRAFFIC Analyses of the Proposals to Amend the CITES Appendices was made possible through the support of: The Commission of the European Union Canadian Wildlife Service Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Department for Nature, the Netherlands Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, Germany Federal Veterinary Office, Switzerland Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Dirección General para la Biodiversidad (Spain) Ministère de l'écologie et du développement durable, Direction de la nature et des paysages (France) IUCN-The World Conservation Union IUCN-The World Conservation Union brings together states, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique global partnership - over 1 000 members in some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. IUCN builds on the strengths of its members, networks and partners to enhance their capacity and to support global alliances to safeguard natural resources at local, regional and global levels. The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions. With 8 000 scientists, field researchers, government officials and conservation leaders, the SSC membership is an unmatched source of information about biodiversity conservation. SSC members provide technical and scientific advice to conservation activities throughout the world and to governments, international conventions and conservation organizations. -

No 811/2008 of 13 August 2008 Suspending the Introduction Into the Community of Specimens of Certain Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

14.8.2008EN Official Journal of the European Union L 219/17 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 811/2008 of 13 August 2008 suspending the introduction into the Community of specimens of certain species of wild fauna and flora THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, — Accipiter erythropus, Aquila rapax, Gyps africanus, Lophaetus occipitalis and Poicephalus gulielmi from Guinea, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, — Hieraaetus ayresii, Hieraaetus spilogaster, Polemaetus bellicosus, Falco chicquera, Varanus ornatus (wild and Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 of ranched specimens) and Calabaria reinhardtii (wild 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna specimens) from Togo, and flora by regulating trade therein (1), and in particular Article 19(2) thereof, — Agapornis pullarius and Poicephalus robustus from Côte d’Ivoire, After consulting the Scientific Review Group, — Stephanoaetus coronatus from Côte d’Ivoire and Togo, Whereas: — Pyrrhura caeruleiceps from Colombia; Pyrrhura pfrimeri (1) Article 4(6) of Regulation (EC) No 338/97 provides that from Brazil, the Commission may establish restrictions to the intro duction of certain species into the Community in accordance with the conditions laid down in points (a) — Brookesia decaryi, Uroplatus ebenaui, Uroplatus fimbriatus, to (d) thereof. Furthermore, implementing measures for Uroplatus guentheri, Uroplatus henkeli, Uroplatus lineatus, such restrictions have been laid down in Commission Uroplatus malama, Uroplatus phantasticus, Uroplatus Regulation (EC) No 865/2006 of 4 May 2006 laying pietschmanni, Uroplatus sikorae, Euphorbia ankarensis, down detailed rules concerning the implementation of Euphorbia berorohae, Euphorbia bongolavensis, Euphorbia Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 of the protection duranii, Euphorbia fiananantsoae, Euphorbia iharanae, of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade Euphorbia labatii, Euphorbia lophogona, Euphorbia 2 therein ( ). -

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History Database

Literature Cited in Lizards Natural History database Abdala, C. S., A. S. Quinteros, and R. E. Espinoza. 2008. Two new species of Liolaemus (Iguania: Liolaemidae) from the puna of northwestern Argentina. Herpetologica 64:458-471. Abdala, C. S., D. Baldo, R. A. Juárez, and R. E. Espinoza. 2016. The first parthenogenetic pleurodont Iguanian: a new all-female Liolaemus (Squamata: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. Copeia 104:487-497. Abdala, C. S., J. C. Acosta, M. R. Cabrera, H. J. Villaviciencio, and J. Marinero. 2009. A new Andean Liolaemus of the L. montanus series (Squamata: Iguania: Liolaemidae) from western Argentina. South American Journal of Herpetology 4:91-102. Abdala, C. S., J. L. Acosta, J. C. Acosta, B. B. Alvarez, F. Arias, L. J. Avila, . S. M. Zalba. 2012. Categorización del estado de conservación de las lagartijas y anfisbenas de la República Argentina. Cuadernos de Herpetologia 26 (Suppl. 1):215-248. Abell, A. J. 1999. Male-female spacing patterns in the lizard, Sceloporus virgatus. Amphibia-Reptilia 20:185-194. Abts, M. L. 1987. Environment and variation in life history traits of the Chuckwalla, Sauromalus obesus. Ecological Monographs 57:215-232. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2003. Anfibios y reptiles del Uruguay. Montevideo, Uruguay: Facultad de Ciencias. Achaval, F., and A. Olmos. 2007. Anfibio y reptiles del Uruguay, 3rd edn. Montevideo, Uruguay: Serie Fauna 1. Ackermann, T. 2006. Schreibers Glatkopfleguan Leiocephalus schreibersii. Munich, Germany: Natur und Tier. Ackley, J. W., P. J. Muelleman, R. E. Carter, R. W. Henderson, and R. Powell. 2009. A rapid assessment of herpetofaunal diversity in variously altered habitats on Dominica. -

Darwin Initiative Annual Report

Darwin Initiative Annual Report Important note: To be completed with reference to the Reporting Guidance Notes for Project Leaders: it is expected that this report will be about 10 pages in length, excluding annexes Submission Deadline: 30 April 2013 Project Reference 19-014 Project Title Implementing CITES in Madagascar Host Country/ies Madagascar UK contract holder institution University of Kent Host country partner Madagasikara Voakajy institutions Other partner institutions - Management Authority CITES Madagascar - Scientific Authority CITES Madagascar Darwin Grant Value £254,788 Start/end dates of project 1 April 2012 – 31 March 2015 Reporting period and number 1 April 2012 to March 2013 Annual Report 1 Project Leader name Richard A. Griffiths Project website www.madagasikara-voakajy.org Report authors, main Christian J. Randrianantoandro, Julie H. Razafimanahaka, contributors and date Richard Jenkins, Richard A. Griffiths 29 April 2013 Madagascar is underachieving in its implementation of CITES Article IV, on the regulation of trade in specimens of species included in Appendix II. There is a concern that unless significant improvements are made, both the number of species and individuals exported will become so few as to jeopardize the potential wider benefits of the trade to conservation and livelihoods. In 2011, there were 141 Malagasy animal species on Appendix II of CITES and most had either been suspended from the trade (48 chameleons and 28 geckos) or had attracted scrutiny from the CITES Animals Committee (e.g. Mantella frogs, Uroplatus lizards), indicating actual or potential problems with the implementation of the convention. Moreover, CITES exports provide little benefits to local livelihoods or biodiversity conservation. -

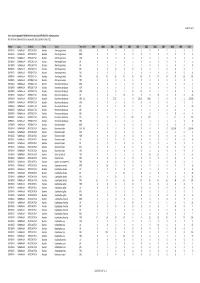

Gross Trade in Appendix II FAUNA (Direct Trade Only), 1999-2010 (For

AC25 Inf. 5 (1) Gross trade in Appendix II FAUNA (direct trade only), 1999‐2010 (for selection process) N.B. Data from 2009 and 2010 are incomplete. Data extracted 1 April 2011 Phylum Class TaxOrder Family Taxon Term Unit 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Total CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia BOD 0 00001000102 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia BON 0 00080000008 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia HOR 0 00000110406 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia LIV 0 00060000006 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKI 1 11311000008 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKP 0 00000010001 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia SKU 2 052101000011 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Ammotragus lervia TRO 15 42 49 43 46 46 27 27 14 37 26 372 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Antilope cervicapra TRO 0 00000020002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae BOD 0 00100001002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae HOP 0 00200000002 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae HOR 0 0010100120216 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae LIV 0 0 5 14 0 0 0 30 0 0 0 49 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae MEA KIL 0 5 27.22 0 0 272.16 1000 00001304.38 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae MEA 0 00000000101 CHORDATA MAMMALIA ARTIODACTYLA Bovidae Bison bison athabascae -

COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2017/1915 Of

20.10.2017 EN Official Journal of the European Union L 271/7 COMMISSION IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2017/1915 of 19 October 2017 prohibiting the introduction into the Union of specimens of certain species of wild fauna and flora THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 338/97 of 9 December 1996 on the protection of species of wild fauna and flora by regulating trade therein (1), and in particular Article 4(6) thereof, Whereas: (1) The purpose of Regulation (EC) No 338/97 is to protect species of wild fauna and flora and to guarantee their conservation by regulating trade in animal and plant species listed in its Annexes. The species listed in the Annexes include the species set out in the Appendices to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora signed in 1973 (2) (the Convention) as well as species whose conservation status requires that trade from, into and within the Union be regulated or monitored. (2) Article 4(6) of Regulation (EC) No 338/97 provides that the Commission may establish restrictions to the introduction of specimens of certain species into the Union in accordance with the conditions laid down in points (a) to (d) thereof. (3) On the basis of recent information, the Scientific Review Group established pursuant to Article 17 of Regulation (EC) No 338/97 has concluded that the conservation status of certain species listed in Annex B to Regulation (EC) No 338/97 would be seriously jeopardised if their introduction into the Union from certain countries of origin is not prohibited. -

Biologie, Ecologie Et Conservation Animales ETUDE ECO-BIOLOGIQUES DES UROPLATE

UNIVERSITE D’ANTANANARIVO FACULTE DES SCIENCES DEPARTEMENT DE BIOLOGIE ANIMALE DEPARTEMENT DE BIOLOGIE ANIMALE Latimeria chalumnae MEMOIRE POUR L’OBTENTION DU Diplôme d’Etudes Approfondies (D.E.A.) Formation Doctorale : Sciences de la vie Option : Biologie, Ecologie et Conservation Animales ETUDE ECO-BIOLOGIQUES DES UROPLATES ET IMPLICATION DES ANALYSES PHYLOGENETIQUES DANS LEUR SYSTEMATIQUE Présenté par : Melle RATSOAVINA Mihaja Fanomezana Devant le JURY composé de : Président : Madame RAMILIJAONA RAVOAHANGIMALALA Olga, Professeur Titulaire Rapporteurs : Madame RAZAFIMAHATRATRA Emilienne, Maître de Conférences Examinateurs: Madame RAZAFINDRAIBE Hanta, Maître de conférences Monsieur EDWARD LOUIS, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, PhD Soutenu publiquement le 27 Février 2009 ________________________________________________________________Remerciements REMERCIEMENTS Cette étude a été réalisée dans le cadre de l’accord de collaboration entre le Département de Biologie Animale, Faculté des Sciences, Université d’Antananarivo et Henry Doorly Zoo Omaha. Nebraska. USA, dans le cadre du projet Madagascar Biogeography Project (MBP). Je tiens à exprimer ma profonde reconnaissance à: - Madame RAMILIJAONA RAVOAHANGIMALALA Olga, Professeur Titulaire, Responsable de la formation doctorale, d'avoir accepté de présider ce mémoire et consacré son précieux temps pour la commission de lecture. - Madame RAZAFIMAHATRATRA Emilienne, Maître de conférences, encadreur et rapporteur qui a accepté de diriger et de corriger ce mémoire. Je la remercie pour ses nombreux conseils. - Madame RAZAFINDRAIBE Hanta, Maître de conférences, qui a accepté de faire partie de la commission de lecture, de juger ce travail et de figurer parmi les membres du jury. - Monsieur Edward LOUIS, Doctor of Veterinary Medecine, PhD d’être parmi les membres du jury et qui m’a permis d’avoir intégrer l’équipe de HDZ et de m’avoir inculqué les a priori des travaux de recherche. -

Reglamento De Ejecución (Ue)

20.10.2017 ES Diario Oficial de la Unión Europea L 271/7 REGLAMENTO DE EJECUCIÓN (UE) 2017/1915 DE LA COMISIÓN de 19 de octubre de 2017 por el que se prohíbe la introducción en la Unión de especímenes de determinadas especies de fauna y flora silvestres LA COMISIÓN EUROPEA, Visto el Tratado de Funcionamiento de la Unión Europea, Visto el Reglamento (CE) n.o 338/97 del Consejo, de 9 de diciembre de 1996, relativo a la protección de especies de la fauna y flora silvestres mediante el control de su comercio (1), y en particular su artículo 4, apartado 6, Considerando lo siguiente: (1) El Reglamento (CE) n.o 338/97 tiene como finalidad proteger las especies de fauna y flora silvestres y asegurar su conservación controlando el comercio de las especies de fauna y flora incluidas en sus anexos. Entre las especies que figuran en los anexos se encuentran las incluidas en los apéndices de la Convención sobre el Comercio Internacional de Especies Amenazadas de Fauna y Flora Silvestres firmada en 1973 (2) (la Convención), así como las especies cuyo estado de conservación exige regular o supervisar su comercio dentro de la Unión, o con origen o destino en la Unión. (2) De acuerdo con el artículo 4, apartado 6, del Reglamento (CE) n.o 338/97, la Comisión puede restringir la introducción de especímenes de determinadas especies en la Unión de acuerdo con las condiciones establecidas en sus letras a) a d). (3) Basándose en información reciente, el Grupo de Revisión Científica creado de conformidad con el artículo 17 del Reglamento (CE) n.o 338/97 ha llegado a la conclusión de que el estado de conservación de algunas especies incluidas en el anexo B del Reglamento (CE) n.o 338/97 se vería seriamente afectado si no se prohibiera su introducción en la Unión desde determinados países de origen. -

Tesi Dottorato

1 UNIVERSIT Á DEGLI STUDI F EDERICO II FACOLT Á DI SCIENZE MATEMATICHE FISICHE E NATURALI Dottorato di ricerca in Biologia Avanzata indirizzo in Biologia Evoluzionistica (ciclo XVIII) Radiazione evolutiva dei Gecconidi africani: un approccio cromosomico e molecolare Tutore: Candidato: Ch.mo Prof . GAETANO ODIERNA Dott. GENNARO APREA Coordinatore: Ch.ma Prof.ssa SILVANA FILOSA 2 3 Indice 1. Introduzione 5 1,1 Evoluzione e filogenesi dei Gekkota 5 1,2 I cromosomi e il loro ruolo nei processi di speciazione 8 1,2a L’evoluzione cromosomica nei Gekkota 11 1,3 I marcatori molecolari 12 1,3a Il DNA mitocondriale 12 1,3b Il DNA nucleare 13 1,3b1 Il DNA ribosomiale 14 1,3b2 Il DNA a sequenza unica 16 1,3b3 Il DNA satellite 17 2. Scopo 21 3. Materiali e Metodi 28 3,1 Specie utilizzate e loro provenienza 28 3,2 Analisi citologiche: Metodiche impiegate 35 3,3 Analisi molecolari: Metodiche impiegate 36 3.3a DNA altamente ripetuto 40 4. Risultati 47 4,1 Phelsuma 47 4,1a Morfologia e NOR 47 4,1b Distribuzione e composizione della eterocromatina 47 4,2 Uroplatus 47 4,2a Morfologia e NOR 47 4,2b Distribuzione e composizione della eterocromatina 48 4,3 Paroedura 48 4,3a Morfologia e NOR 48 4,3b Distribuzione e composizione della eterocromatina 67 4,4 Microscalabotes e Lygodactylus 67 4,4a Morfologia e NOR 67 4,4b Distribuzione e composizione della eterocromatina 68 4,5 Ebenavia-Matoatoa-Blaesiodactylus-Geckolepis 68 4,5a Morfologia e NOR 68 4,5b Distribuzione e composizione della eterocromatina 68 4,6 Tarentola 68 4,6a Morfologia e NOR 68 4,6b Distribuzione e composizione della eterocromatina 77 4 4,7 Tropiocolotes-Stenodactylus-Ptyodactylus 77 4,1a Morfologia e NOR 77 4,1b Distribuzione e composizione della eterocromatina 77 5. -

Lizards & Snakes: Alive!

LIZARDSLIZARDS && SNAKES:SNAKES: ALIVE!ALIVE! EDUCATOR’SEDUCATOR’S GUIDEGUIDE www.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakeswww.sdnhm.org/exhibits/lizardsandsnakes Inside: • Suggestions to Help You Come Prepared • Must-Read Key Concepts and Background Information • Strategies for Teaching in the Exhibition • Activities to Extend Learning Back in the Classroom • Map of the Exhibition to Guide Your Visit • Correlations to California State Standards Special thanks to the Ellen Browning Scripps Foundation and the Nordson Corporation Foundation for providing underwriting support of the Teacher’s Guide KEYKEY CONCEPTSCONCEPTS Squamates—legged and legless lizards, including snakes—are among the most successful vertebrates on Earth. Found everywhere but the coldest and highest places on the planet, 8,000 species make squamates more diverse than mammals. Remarkable adaptations in behavior, shape, movement, and feeding contribute to the success of this huge and ancient group. BEHAVIOR Over 45O species of snakes (yet only two species of lizards) An animal’s ability to sense and respond to its environment is are considered to be dangerously venomous. Snake venom is a crucial for survival. Some squamates, like iguanas, rely heavily poisonous “soup” of enzymes with harmful effects—including on vision to locate food, and use their pliable tongues to grab nervous system failure and tissue damage—that subdue prey. it. Other squamates, like snakes, evolved effective chemore- The venom also begins to break down the prey from the inside ception and use their smooth hard tongues to transfer before the snake starts to eat it. Venom is delivered through a molecular clues from the environment to sensory organs in wide array of teeth.