Lizards & Snakes: Alive!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veiled Chameleon Care Sheet Because We Care !!!

Veiled Chameleon Care Sheet Because we care !!! 1250 Upper Front Street, Binghamton, NY 13901 607-723-2666 Congratulations on your new pet. The popularity of the veiled chameleon is due to a number of factors: veiled chameleons are relatively hardy, large, beautiful, and prolific. Veiled chameleons are native to Yemen and southern Saudi Arabia, they are quite tolerant of tem- perature and humidity extremes, which contributes to its hardiness as a captive. Veiled chameleons are among the easiest chameleons to care for, but they still require careful attention. They range in size from 6-12 inches and will live up to five years with the proper care. Males tend to be larger and more colorful than females. With their ability to change colors, prehensile tails, independently moving eyes and stuttering walk make them fascinating to watch. They become stressed very easily so regular handling is not recommended. HOUSING A full-screen enclosure is a must for veiled chameleons. Zoomed’s ReptiBreeze is an ideal habitat. Glass aquariums can lead to respiratory diseases due to the stagnant air not being circulated, and they will be stressed if they can see their reflection. These Chameleons also need a large enclosure to climb around in because smaller enclosures will stress them. A 3’x3’x3’ or 2’x2’x4’ habitat is best, but larger is bet- ter. Chameleons should be house separately to avoid fighting. The interior of the enclosure should be furnished with medium sized vines and foliage for the chameleons to hide in. The medium sized vines provide important horizontal perches for the chameleon to rest and bask. -

Laws of Malaysia

LAWS OF MALAYSIA ONLINE VERSION OF UPDATED TEXT OF REPRINT Act 716 WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ACT 2010 As at 1 December 2014 2 WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ACT 2010 Date of Royal Assent … … 21 October 2010 Date of publication in the Gazette … … … 4 November 2010 Latest amendment made by P.U.(A)108/2014 which came into operation on ... ... ... ... … … … … 18 April 2014 3 LAWS OF MALAYSIA Act 716 WILDLIFE CONSERVATION ACT 2010 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY Section 1. Short title and commencement 2. Application 3. Interpretation PART II APPOINTMENT OF OFFICERS, ETC. 4. Appointment of officers, etc. 5. Delegation of powers 6. Power of Minister to give directions 7. Power of the Director General to issue orders 8. Carrying and use of arms PART III LICENSING PROVISIONS Chapter 1 Requirement for licence, etc. 9. Requirement for licence 4 Laws of Malaysia ACT 716 Section 10. Requirement for permit 11. Requirement for special permit Chapter 2 Application for licence, etc. 12. Application for licence, etc. 13. Additional information or document 14. Grant of licence, etc. 15. Power to impose additional conditions and to vary or revoke conditions 16. Validity of licence, etc. 17. Carrying or displaying licence, etc. 18. Change of particulars 19. Loss of licence, etc. 20. Replacement of licence, etc. 21. Assignment of licence, etc. 22. Return of licence, etc., upon expiry 23. Suspension or revocation of licence, etc. 24. Licence, etc., to be void 25. Appeals Chapter 3 Miscellaneous 26. Hunting by means of shooting 27. No licence during close season 28. Prerequisites to operate zoo, etc. 29. Prohibition of possessing, etc., snares 30. -

(EU) 2015/56 Оd 15

16.1.2015. HR Službeni list Europske unije L 10/1 II. (Nezakonodavni akti) UREDBE UREDBA KOMISIJE (EU) 2015/56 оd 15. siječnja 2015. o izmjeni, u odnosu na trgovinu vrstama divlje faune i flore, Uredbe (EZ) br. 865/2006 o utvrđivanju detaljnih pravila o provedbi Uredbe Vijeća (EZ) br. 338/97 EUROPSKA KOMISIJA, uzimajući u obzir Ugovor o funkcioniranju Europske unije, uzimajući u obzir Uredbu Vijeća (EZ) br. 338/97 od 9. prosinca 1996. o zaštiti vrsta divlje faune i flore uređenjem trgovine njima (1), a posebno njezin članak 19. stavke 2., 3. i 4., budući da: (1) Za provedbu određenih rezolucija donesenih na šesnaestom sastanku Konferencije potpisnica Konvencije o međunarodnoj trgovini ugroženim vrstama divlje faune i flore (CITES) (3. – 14. ožujka 2013.), u daljnjem tekstu „Konvencija”, neke odredbe treba izmijeniti, a daljnje odredbe treba dodati Uredbi Komisije (EZ) br. 865/2006 (2). (2) Posebno, u skladu s Rezolucijom Konferencije potpisnica CITES-a 16.8, treba umetnuti posebne odredbe namijenjene pojednostavljenju nekomercijalnog prekograničnog prometa glazbenih instrumenata. (3) Iskustvo stečeno provedbom Uredbe (EZ) br. 865/2006, u vezi s Provedbenom uredbom Komisije (EU) br. 792/2012 (3), pokazalo je da neke njezine odredbe treba izmijeniti kako bi se osigurala usklađena i učinkovita provedba Uredbe unutar Unije. To je posebno slučaj kod prvog unošenja u Uniju lovačkih trofeja primjeraka nekih vrsta ili populacija navedenih u Prilogu B Uredbi (EZ) br. 338/97, za koje postoji zabrinutost u pogledu održivosti trgovine lovačkim trofejima ili za koje postoje naznake značajne nezakonite trgovine. U takvim je slučajevima potreban stroži nadzor uvoza u Uniju, a odstupanje utvrđeno člankom 7. -

West Indian Iguana Husbandry Manual

1 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 4 Natural history ............................................................................................................................... 7 Captive management ................................................................................................................... 25 Population management .............................................................................................................. 25 Quarantine ............................................................................................................................... 26 Housing..................................................................................................................................... 26 Proper animal capture, restraint, and handling ...................................................................... 32 Reproduction and nesting ........................................................................................................ 34 Hatchling care .......................................................................................................................... 40 Record keeping ........................................................................................................................ 42 Husbandry protocol for the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima)................................. 43 Nutrition ...................................................................................................................................... -

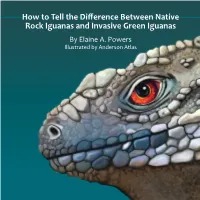

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas by Elaine A

How to Tell the Difference Between Native Rock Iguanas and Invasive Green Iguanas By Elaine A. Powers Illustrated by Anderson Atlas Many of the islands in the Caribbean Sea, known as the West Rock Iguanas (Cyclura) Indies, have native iguanas. B Cuban Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila), Cuba They are called Rock Iguanas. C Sister Isles Rock Iguana (Cyclura nubila caymanensis), Cayman Brac and Invasive Green Iguanas have been introduced on these islands and Little Cayman are a threat to the Rock Iguanas. They compete for food, territory D Grand Cayman Blue Iguana (Cyclura lewisi), Grand Cayman and nesting areas. E Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collei), Jamaica This booklet is designed to help you identify the native Rock F Turks & Caicos Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata), Turks and Caicos. Iguanas from the invasive Greens. G Booby Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura carinata bartschi), Booby Cay, Bahamas H Andros Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura), Andros, Bahamas West Indies I Exuma Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura figginsi), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Exumas BAHAMAS J Allen’s Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura cychlura inornata), Exuma Islands, J Islands Bahamas M San Salvador Andros Island H Booby Cay K Anegada Iguana (Cyclura pinguis), British Virgin Islands Allens Cay White G I Cay Ricord’s Iguana (Cyclura ricordi), Hispaniola O F Turks & Caicos L CUBA NAcklins Island M San Salvador Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi), San Salvador, Bahamas Anegada HISPANIOLA CAYMAN ISLANDS K N Acklins Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi nuchalis), Acklins Islands, Bahamas B PUERTO RICO O White Cay Rock Iguana (Cyclura rileyi cristata), Exuma Islands, Bahamas Grand Cayman D C JAMAICA BRITISH P Rhinoceros Iguana (Cyclura cornuta), Hispanola Cayman Brac & VIRGIN Little Cayman E L P Q Mona ISLANDS Q Mona Island Iguana (Cyclura stegnegeri), Mona Island, Puerto Rico Island 2 3 When you see an iguana, ask: What kind do I see? Do you see a big face scale, as round as can be? What species is that iguana in front of me? It’s below the ear, that’s where it will be. -

Activity Budget and Spatial Behavior of the Emerald Tree Boa Corallus Batesii

Activity Budget and Spatial Behavior of the Emerald Tree Boa Corallus batesii Faculty Member #1 Joseph R. Mendelson III Signature Faculty Member #2 Emily G. Weigel Signature 2 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank my primary research advisor, Professor Joseph Mendelson, for your guidance and support. Thank you for inviting me to be a part of the emerald boa project and for investing so much time in helping me to become a scientist. I would also like to thank my second research advisor, Professor Emily Weigel, for helping me to get involved in research. Thank you for all of your help with my statistics and analysis and for providing detailed feedback to help me improve my scientific writing. Next, I would like to thank members of my research team: Liz Haseltine, Sav Berry, and Ellen Sproule. Thank you for organizing this study and for your help analyzing our 1,104 hours of video footage. I would like to thank members of the Spatial Ecology and Paleontology lab for your help in training me to become a better researcher. Thank you to Professor Jenny McGuire, Dr. Sílvia Pineda-Munoz, Dr. Yue Wang, Dr. Rachel Short, and Julia Schap. A special thanks to Ben Shipley and Danny Lauer for teaching me how to use R. Finally, I would like to thank my family for your continuous support while I study to become a wildlife biologist. Thank you for listening to me talk about snakes for the past few years. 3 Abstract Corallus batesii is a boid snake native to the Amazon basin. -

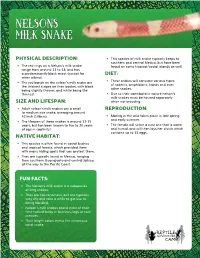

Nelsons Milk Snake

Nelsons Milk SNake PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION: • This species of milk snake typically keeps to southern and central Mexico, but have been • The red rings on a Nelson’s milk snake found on some tropical/costal islands as well. range from around 13 to 18, and has a predominantly black snout (except for DIET: when albino). • These snakes will consume various types • The red bands on the nelson’s milk snake are of rodents, amphibians, lizards and even the thickest stripes on their bodies, with black other snakes. being slightly thinner, and white being the thinnest. • Due to their cannibalistic nature nelson’s milk snakes must be housed separately SIZE AND LIFESPAN: when not breeding. • Adult nelson’s milk snakes are a small REPRODUCTION: to medium size snake, averaging around 42 inch (106cm). • Mating in the wild takes place in late spring and early summer. • The lifespan of these snakes is around 12-15 years, but has been known to live to 20 years • The female will select a nest site that is warm of age in captivity! and humid, and will then lays her clutch which contains up to 15 eggs. NATIVE HABITAT: • This species is often found in costal bushes and tropical forests, which provided them with many hiding spots that can protect them. • They are typically found in Mexico, ranging from southern Guanajuato and central Jalisco, all the way to the Pacific Coast. FUN FACTS: • The Nelson’s milk snake is a subspecies of king snakes. • They are nonvenomous, but are typically very shy and take a while to get use to being handled. -

Aberrant Colourations in Wild Snakes: Case Study in Neotropical Taxa and a Review of Terminology

SALAMANDRA 57(1): 124–138 Claudio Borteiro et al. SALAMANDRA 15 February 2021 ISSN 0036–3375 German Journal of Herpetology Aberrant colourations in wild snakes: case study in Neotropical taxa and a review of terminology Claudio Borteiro1, Arthur Diesel Abegg2,3, Fabrício Hirouki Oda4, Darío Cardozo5, Francisco Kolenc1, Ignacio Etchandy6, Irasema Bisaiz6, Carlos Prigioni1 & Diego Baldo5 1) Sección Herpetología, Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Miguelete 1825, Montevideo 11800, Uruguay 2) Instituto Butantan, Laboratório Especial de Coleções Zoológicas, Avenida Vital Brasil, 1500, Butantã, CEP 05503-900 São Paulo, SP, Brazil 3) Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Zoologia, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Zoologia, Travessa 14, Rua do Matão, 321, Cidade Universitária, 05508-090, São Paulo, SP, Brazil 4) Universidade Regional do Cariri, Departamento de Química Biológica, Programa de Pós-graduação em Bioprospecção Molecular, Rua Coronel Antônio Luiz 1161, Pimenta, Crato, Ceará 63105-000, CE, Brazil 5) Laboratorio de Genética Evolutiva, Instituto de Biología Subtropical (CONICET-UNaM), Facultad de Ciencias Exactas Químicas y Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Misiones, Felix de Azara 1552, CP 3300, Posadas, Misiones, Argentina 6) Alternatus Uruguay, Ruta 37, km 1.4, Piriápolis, Uruguay Corresponding author: Claudio Borteiro, e-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received: 2 April 2020 Accepted: 18 August 2020 by Arne Schulze Abstract. The criteria used by previous authors to define colour aberrancies of snakes, particularly albinism, are varied and terms have widely been used ambiguously. The aim of this work was to review genetically based aberrant colour morphs of wild Neotropical snakes and associated terminology. We compiled a total of 115 cases of conspicuous defective expressions of pigmentations in snakes, including melanin (black/brown colour), xanthins (yellow), and erythrins (red), which in- volved 47 species of Aniliidae, Boidae, Colubridae, Elapidae, Leptotyphlopidae, Typhlopidae, and Viperidae. -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List Common Name Scientific Name Status Snakes Cape cobra Naja nivea Puffadder Bitis arietans Albany adder Bitis albanica very rare Night adder Causes rhombeatus Bergadder Bitis atropos Horned adder Bitis cornuta Boomslang Dispholidus typus Rinkhals Hemachatus hemachatus Herald/Red-lipped snake Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia Olive house snake Lamprophis inornatus Night snake Lamprophis aurora Brown house snake Lamprophis fuliginosus fuliginosus Speckled house snake Homoroselaps lacteus Wolf snake Lycophidion capense Spotted harlequin snake Philothamnus semivariegatus Speckled bush snake Bitis atropos Green water snake Philothamnus hoplogaster Natal green watersnake Philothamnus natalensis occidentalis Shovel-nosed snake Prosymna sundevalli Mole snake Pseudapsis cana Slugeater Duberria lutrix lutrix Common eggeater Dasypeltis scabra scabra Dappled sandsnake Psammophis notosticus Crossmarked sandsnake Psammophis crucifer Black-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus laevissimus Common/Red-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus rufulus Tortoises/terrapins Angulate tortoise Chersina angulata Leopard tortoise Geochelone pardalis Green parrot-beaked tortoise Homopus areolatus Marsh/Helmeted terrapin Pelomedusa subrufa Tent tortoise Psammobates tentorius Lizards/geckoes/skinks Rock Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus niloticus niloticus Water Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus exanthematicus albigularis Tasman's Girdled Lizard Cordylus tasmani Cape Girdled Lizard Cordylus cordylus Southern Rock Agama Agama atra Burrowing -

Controlled Animals

Environment and Sustainable Resource Development Fish and Wildlife Policy Division Controlled Animals Wildlife Regulation, Schedule 5, Part 1-4: Controlled Animals Subject to the Wildlife Act, a person must not be in possession of a wildlife or controlled animal unless authorized by a permit to do so, the animal was lawfully acquired, was lawfully exported from a jurisdiction outside of Alberta and was lawfully imported into Alberta. NOTES: 1 Animals listed in this Schedule, as a general rule, are described in the left hand column by reference to common or descriptive names and in the right hand column by reference to scientific names. But, in the event of any conflict as to the kind of animals that are listed, a scientific name in the right hand column prevails over the corresponding common or descriptive name in the left hand column. 2 Also included in this Schedule is any animal that is the hybrid offspring resulting from the crossing, whether before or after the commencement of this Schedule, of 2 animals at least one of which is or was an animal of a kind that is a controlled animal by virtue of this Schedule. 3 This Schedule excludes all wildlife animals, and therefore if a wildlife animal would, but for this Note, be included in this Schedule, it is hereby excluded from being a controlled animal. Part 1 Mammals (Class Mammalia) 1. AMERICAN OPOSSUMS (Family Didelphidae) Virginia Opossum Didelphis virginiana 2. SHREWS (Family Soricidae) Long-tailed Shrews Genus Sorex Arboreal Brown-toothed Shrew Episoriculus macrurus North American Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Old World Water Shrews Genus Neomys Ussuri White-toothed Shrew Crocidura lasiura Greater White-toothed Shrew Crocidura russula Siberian Shrew Crocidura sibirica Piebald Shrew Diplomesodon pulchellum 3. -

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use.