1The Court Recognizes That in Its Discretion, It Could Grant the Motion As Uncontested Pursuant to Local Rule 7.1(C)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Re Ford Motor Company Securities Litigation 00-CV-74233

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION Master C e No. 00-74233 In re FORD MOTOR CO. CLASS A TION SECURITIES LITIGATION The Honorable Avern Cohn DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL CONSOLIDATED COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 l r" CJ'^ zti ^ OVERVIEW 1. This is an action on behalf of all purchasers of the common stock of Ford Motor Company, Inc. ("Ford") between March 31, 1998 and August 31, 2000 (the "Class Period"). This action arises out of the conduct of Ford to conceal from the investment community defects in Ford's Explorer sport-utility vehicles equipped with steel-belted radial ATX tires manufactured by Bridgestone Corp.'s U.S. subsidiary, Bridgestone/Firestone, Inc. ("Bridgestone/Firestone"). The Explorer is Ford's most important product and its largest selling vehicle, which has accounted for 25% of Ford's profits during the 1990s. Due to the success of the Explorer, Ford became Bridgestone/ Firestone's largest customer and sales of ATX tires have been the largest source of revenues and profits for Bridgestone/Firestone during the 1990s. During the Class Period, Ford and Bridgestone had knowledge ofthousands ofclaims for and complaints concerning ATX tire failures, especially ATX tires manufactured at Bridgestone/Firestone's Decatur, Illinois plant during and after a bitter 1994-1996 strike, due to design and manufacturing defects in, and under-inflation of, the tires, which, when combined with the unreasonably dangerous and unstable nature of the Explorer, resulted in over 2,200 rollover accidents, 400 serious injuries and 174 fatalities by 2000. -

UVA-BC-0145 FORD's E-BUSINESS STRATEGY in the Fall of 1999, Jacques Nasser, Ford Motor Company President and Chief Executive O

Graduate School of Business Administration UVA-BC-0145 University of Virginia FORD’S E-BUSINESS STRATEGY In the fall of 1999, Jacques Nasser, Ford Motor Company president and chief executive officer, announced a grand new vision for the firm: to become the “world’s leading consumer company providing automotive products and services.” Key to that dream was the transformation of the business using Web technologies. The company that taught the world how to mass- produce cars for the consumer market was going to become the leading e-business firm. Brian P. Kelly, Ford’s e-business vice president, described Ford’s plan to rebuild itself as a move to “consumercentric” from “dealercentric,” and stated that Ford would transform itself from being a “manufacturer to dealers” into a “marketer to consumers.” Our consumer-connect business has a totally integrated strategy to reach the consumer in conjunction with our dealers at every touch point. Ford continues to be at the forefront, integrating our global e-commerce activity from the consumer back through the entire supply chain, including linking our Customer Assistance Centers and in-vehicle communications.1 New Web sites were launched for buyers and owners. In-car computer and communications services were announced that would bring travel, security, entertainment, and Web access to the motorist and an electronic connection between consumers and the Ford Motor Company. In February, the company announced it was purchasing Internet PCs for all employees, “to reach its vision of being on the leading edge of technology and connect more closely with its customers.” In March 2000, the company announced the creation of a business- to-business integrated supplier exchange through a single global portal, a joint venture with GM and DaimlerChrysler to create the world’s largest virtual marketplace. -

Important Notice

IMPORTANT NOTICE THIS OFFERING IS AVAILABLE ONLY TO INVESTORS WHO ARE NON-U.S. PERSONS (AS DEFINED IN REGULATION S UNDER THE UNITED STATES SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 (THE “SECURITIES ACT”) (“REGULATION S”)) LOCATED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. IMPORTANT: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the attached document (the “document”) and you are therefore advised to read this carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the document. In accessing the document, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from Sky plc (formerly known as British Sky Broadcasting Group plc) (the “Issuer”), Sky Group Finance plc (formerly known as BSkyB Finance UK plc), Sky UK Limited (formerly known as British Sky Broadcasting Limited), Sky Subscribers Services Limited or Sky Telecommunications Services Limited (formerly known as BSkyB Telecommunications Services Limited) (together, the “Guarantors”) or Barclays Bank PLC or Société Générale (together, the “Joint Lead Managers”) as a result of such access. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE IN THE UNITED STATES OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE SECURITIES AND THE GUARANTEES HAVE NOT BEEN, AND WILL NOT BE, REGISTERED UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT, OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OF THE UNITED STATES OR OTHER JURISDICTION AND THE SECURITIES AND THE GUARANTEES MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, WITHIN THE UNITED STATES OR TO, OR FOR THE ACCOUNT OR BENEFIT OF, U.S. -

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All Rights Reserved

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All rights reserved. Public Citizen Foundation 1600 20th St. NW Washington, D.C. 20009 www.citizen.org ISBN: 978-1-58231-099-2 Doyle Printing, 2016 Printed in the United States of America PUBLIC CITIZEN THE SENTINEL OF DEMOCRACY CONTENTS Preface: The Biggest Get ...................................................................7 Introduction ....................................................................................11 1 Nader’s Raiders for the Lost Democracy....................................... 15 2 Tools for Attack on All Fronts.......................................................29 3 Creating a Healthy Democracy .....................................................43 4 Seeking Justice, Setting Precedents ..............................................61 5 The Race for Auto Safety ..............................................................89 6 Money and Politics: Making Government Accountable ..............113 7 Citizen Safeguards Under Siege: Regulatory Backlash ................155 8 The Phony “Lawsuit Crisis” .........................................................173 9 Saving Your Energy .................................................................... 197 10 Going Global ...............................................................................231 11 The Fifth Branch of Government................................................ 261 Appendix ......................................................................................271 Acknowledgments ........................................................................289 -

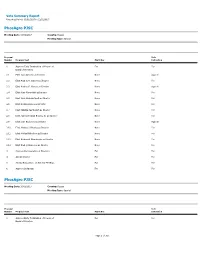

Vote Summary Report Reporting Period: 10/01/2017 to 12/31/2017

Vote Summary Report Reporting Period: 10/01/2017 to 12/31/2017 PhosAgro PJSC Meeting Date: 10/02/2017 Country: Russia Meeting Type: Special Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Early Termination of Powers of For For Board of Directors 2.1 Elect Igor Antoshin as Director None Against 2.2 Elect Andrey A. Guryev as Director None For 2.3 Elect Andrey G. Guryev as Director None Against 2.4 Elect Yury Krugovykh as Director None For 2.5 Elect Sven Ombudstvedt as Director None For 2.6 Elect Roman Osipov as Director None For 2.7 Elect Natalya Pashkevich as Director None For 2.8 Elect James Beeland Rogers, Jr. as Director None For 2.9 Elect Ivan Rodionov as Director None Against 2.10 Elect Marcus J. Rhodes as Director None For 2.11 Elect Mikhail Rybnikov as Director None For 2.12 Elect Aleksandr Sharabayko as Director None For 2.13 Elect Andrey Sharonov as Director None For 3 Approve Remuneration of Directors For For 4 Amend Charter For For 5 Amend Regulations on General Meetings For For 6 Approve Dividends For For PhosAgro PJSC Meeting Date: 10/02/2017 Country: Russia Meeting Type: Special Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Early Termination of Powers of For For Board of Directors Page 1 of 767 Vote Summary Report Reporting Period: 10/01/2017 to 12/31/2017 PhosAgro PJSC Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Mgmt Rec Instruction 2.1 Elect Igor Antoshin as Director None Against 2.2 Elect Andrey A. -

2010 BHP Billiton Summary Review

In this Summary Review People and Safety Our results at a glance Karen Wood describes our commitment to our people A snapshot of our results and five-year financial summary and safety, including our approach to leadership See page 2 See page 24 Chairman’s Review – Environment and Communities Our strategy delivers The way we manage our responsibilities to the An overview of the year by Jacques Nasser AO environment and communities in which we operate See page 4 is explained by J Michael Yeager See page 26 Chief Executive Officer’s Report – An unchanged strategy Board of Directors The year in review, by Marius Kloppers The profiles of BHP Billiton’s Directors See page 6 See page 28 Customer Sector Groups Group Management Committee An update from each of our Customer Sector Groups, Profiles of the senior management team at BHP Billiton providing a snapshot of BHP Billiton’s operational performance See page 31 See page 13 Corporate Governance Summary Finance and Marketing overview A summary of BHP Billiton governance An outline of our financial position from Alex Vanselow and See page 32 an update on our marketing operations by Alberto Calderon Remuneration Summary See page 20 Key policy principles and information about Performance update of our operations our remuneration Details of key achievements in Ferrous and Coal See page 34 by Marcus Randolph and highlights of the year Shareholder information in Non-Ferrous by Andrew Mackenzie Key dates and information relevant for shareholders, See page 22 including our dividend policy and payments See page 36 Corporate Directory A list of major BHP Billiton offices and share registries See Inside Back Cover This Summary Review is designed to provide you with an update on This Summary Review is not a substitute for the Annual Report 2010 the operations and performance of BHP Billiton over the year ended and does not contain all the information needed to give as full an 30 June 2010 in a concise and easy-to-read format. -

SATURDAY 28TH JULY 06:00 Breakfast 10:00 Saturday Kitchen

SATURDAY 28TH JULY All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 06:00 Breakfast 09:50 The Big Bang Theory 06:00 The Forces 500 Back-to-back Music! 10:00 Saturday Kitchen Live 10:15 The Cars That Made Britain Great 07:00 The Forces 500 Back-to-back Music! 11:30 Nadiya's Family Favourites 09:25 Saturday Morning with James Martin 11:05 Carnage 08:00 I Dream of Jeannie 12:00 Bargain Hunt 11:20 James Martin's American Adventure 11:55 Brooklyn Nine-Nine 08:30 I Dream of Jeannie 13:00 BBC News 11:50 Eat, Shop, Save 12:20 Star Trek: Voyager 09:00 I Dream of Jeannie 13:15 Wanted Down Under 12:20 Love Your Garden 13:00 Shortlist 09:30 I Dream of Jeannie 14:00 Money for Nothing 13:20 ITV Lunchtime News 13:05 Modern Family 10:00 I Dream of Jeannie 14:45 Garden Rescue 13:30 ITV Racing: Live from Ascot 13:30 Modern Family 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 15:30 Escape to the Country 16:00 The Chase 13:55 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 11:00 Hogan's Heroes 16:30 Wedding Day Winners 17:00 WOS Wrestling 14:20 The Fresh Prince of Bel Air 11:30 Hogan's Heroes 17:25 Monsters vs Aliens 14:45 Ashley Banjo's Secret Street Crew 12:00 Hogan's Heroes 18:50 BBC News 15:35 Jamie and Jimmy's Friday Night Feast 12:30 Hogan's Heroes 19:00 BBC London News 16:30 Bang on Budget 13:00 Airwolf The latest news, sport and weather from 17:15 Shortlist 14:00 Goodnight Sweetheart London. -

The Man Behind the Cloud an Interview with Vmware’S Paul Maritz

fear, greed and fairy tales • p.j. o’rourke is out off wworkrk It Pays to Be Lucky Where Have the Leaders Gone? Formula One’s Benign Despot The Buck Starts Here The Man Behind the Cloud An Interview with VMware’s Paul Maritz Q1.2012.2012 chief executive officer Gary Burnison chief marketing officer Michael Distefano editor-in-chief Joel Kurtzman creative director Joannah Ralston circulation director Peter Pearsall marketing operations manager Reonna Johnson board of advisors Sergio Averbach Cheryl Buxton Joe Griesedieck Byrne Mulrooney Kristen Badgley Dennis Carey Robert Hallagan Indranil Roy Michael Bekins Bob Damon Katie Lahey Jane Stevenson Stephen Bruyant-Langer Ana Dutra Robert McNabb Anthony Vardy contributing editors Chris Bergonzi Stephanie Mitchell David Berreby P.J. O’Rourke Lawrence M. Fisher Glenn Rifkin Victoria Griffi th Adrian Wooldridge Cover photo of Paul Maritz: The Korn/Ferry International Briefi ngs on Talent and Leadership is published Jeff Singer quarterly by the Korn/Ferry Institute. The Korn/Ferry Institute was founded to serve Cover illustration: as a premier global voice on a range of talent management and leadership issues. The Zé Otavio Institute commissions, originates and publishes groundbreaking research utilizing Korn/ Ferry’s unparalleled expertise in executive recruitment and talent development combined with its preeminent behavioral research library. The Institute is dedicated to improving the state of global human capital for businesses of all sizes around the world. ISSN 1949-8365 Copyright 2012, Korn/Ferry International Requests for additional copies should be sent directly to: Briefi ngs Magazine 1900 Avenue of the Stars, Suite 2600, Los Angeles, CA 90067 briefi [email protected] Briefi ngs is produced with solar power, FSC-certifi ed Advertising Sales Representative: paper, and soy-based inks, Erica Springer + Associates, LLC in a fully sustainable and 1355 S. -

SATURDAY 24TH FEBRUARY 06:00 Breakfast 10:00 Winter Olympics 12:00 Football Focus 13:00 BBC News 13:15 Winter Olympics~ 16:00 Si

SATURDAY 24TH FEBRUARY All programme timings UK All programme timings UK All programme timings UK 06:00 Breakfast 09:50 Black-ish 06:00 Forces News 10:00 Winter Olympics 09:25 ITV News 10:15 There's Something About Megan 06:30 The Forces Sports Show 09:30 Saturday Morning with James Marr 11:05 Sinbad 07:00 Sea Power 11:25 Dancing on Ice 11:55 Brooklyn Nine-Nine 07:30 Airwolf Celebrity ice-skating contest. 12:20 Star Trek: Voyager 08:30 Flying Through Time 13:20 ITV News and Weather 13:05 Shortlist 09:00 Flying Through Time 13:30 Six Nations 13:10 Malcolm in the Middle 09:30 Flying Through Time Ireland v Wales. 13:35 Malcolm in the Middle 10:00 The Forces Sports Show 16:30 ITV News and Weather 14:00 Young & Hungry 10:30 Hogan's Heroes 16:50 Local News and Weather 14:20 Young & Hungry 11:00 Hogan's Heroes All the very latest local news and weather. 14:45 Spa Wars 11:30 Hogan's Heroes 17:00 The Chase 15:35 Don't Tell the Bride 12:00 Hogan's Heroes Quiz show in which four contestants must pit 16:25 The Middle 12:30 Hogan's Heroes 12:00 Football Focus their wits against The Chaser. 16:45 Modern Family 13:00 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 13:00 BBC News 18:00 Take Me Out 17:05 Shortlist 13:30 R Lee Ermey's Mail Call 13:15 Winter Olympics~ 10th Anniversary Special. -

Bskyb Finance UK

PROSPECTUS BSkyB Finance UK plc (incorporated with limited liability in England and Wales) (Registered Number 05576975) and British Sky Broadcasting Group plc (incorporated with limited liability in England and Wales) (Registered Number 02247735) £1,000,000,000 Euro Medium Term Note Programme unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed by BSkyB Finance UK plc BSkyB Publications Limited British Sky Broadcasting Group plc British Sky Broadcasting Limited Sky Subscribers Services Limited Sky In-Home Service Limited and BSkyB Investments Limited Under the Euro Medium Term Note Programme described in this Prospectus (the “Programme”), BSkyB Finance UK plc (“BSkyB Finance”) and British Sky Broadcasting Group plc (“BSkyB”) (each an “Issuer” and together, the “Issuers”), subject to compliance with all relevant laws, regulations and directives, may from time to time issue Euro Medium Term Notes (the “Notes”). Notes issued by BSkyB Finance will be guaranteed by BSkyB, British Sky Broadcasting Limited (“BSkyB Limited”), BSkyB Publications Limited (“BSkyB Publications”), Sky Subscribers Services Limited (“Sky Subscribers”), Sky In-Home Service Limited (“Sky In-Home”) and BSkyB Investments Limited (“BSkyB Investments”). Notes issued by BSkyB will be guaranteed by BSkyB Finance, BSkyB Limited, BSkyB Publications, Sky Subscribers, Sky In-Home and BSkyB Investments (when acting in its capacity as guarantor of the relevant Notes, each such entity (subject to change in accordance with Condition 3(c)) and any acceding guarantor is referred to as a “Guarantor” and the Guarantors of the Notes issued by BSkyB Finance are together, referred to herein as the “Guarantors”). The aggregate nominal amount of Notes outstanding will not at any time exceed £1,000,000,000 (or the equivalent in other currencies). -

Important Notice

IMPORTANT NOTICE THIS OFFERING IS AVAILABLE ONLY TO INVESTORS WHO ARE NON-U.S. PERSONS (AS DEFINED IN REGULATION S UNDER THE UNITED STATES SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 (THE “SECURITIES ACT”) (“REGULATION S”)) LOCATED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. IMPORTANT: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the attached document (the “document”) and you are therefore advised to read this carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the document. In accessing the document, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from British Sky Broadcasting Group plc (the “Issuer”), BSkyB Finance UK plc, British Sky Broadcasting Limited, Sky Subscribers Services Limited or Sky In-Home Service Limited (together, the “Guarantors”) or Bank of China Limited, London Branch, Barclays Bank PLC, BNP Paribas, DNB Markets, a division of DNB Bank ASA, HSBC Bank plc, J.P. Morgan Securities plc, Lloyds Bank plc, Mitsubishi UFJ Securities International plc, Mizuho International plc, Morgan Stanley & Co. International plc, SMBC Nikko Capital Markets Limited, Société Générale, The Royal Bank of Scotland plc or UniCredit Bank AG (together, the “Joint Lead Managers”) as a result of such access. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE IN THE UNITED STATES OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE SECURITIES AND THE GUARANTEES HAVE NOT BEEN, AND WILL NOT BE, REGISTERED UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT, OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OF THE UNITED STATES OR OTHER JURISDICTION AND THE SECURITIES AND THE GUARANTEES MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, WITHIN THE UNITED STATES OR TO, OR FOR THE ACCOUNT OR BENEFIT OF, U.S. -

21ST CENURY FOX, INC. / SKY PLC MERGER INQUIRY Response to the Provisional Findings 1. INTRODUCTION and EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Th

21ST CENURY FOX, INC. / SKY PLC MERGER INQUIRY Response to the Provisional Findings 1. INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 This submission is made on behalf of 21st Century Fox, Inc. (21CF) in response to the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA)’s provisional findings (the Provisional Findings) in relation to 21CF’s proposed acquisition of the remaining shares in Sky plc (Sky) (the Transaction). It should be read in conjunction with the additional submissions provided as Annex 1,1 prepared by Charles River Associates (CRA), which addresses the Provisional Findings from an economic perspective, and Annex 2,2 which responds to specific elements of the Provisional Findings in greater detail. 1.2 The Provisional Findings purport to show that the Transaction would result in a significant increase in the control of the Murdoch Family Trust (MFT) over Sky News and that, as a result of this increase in control, the diversity of viewpoints to which UK audiences are exposed would be reduced, and the political influence of the MFT enhanced, to such an extent that there can no longer be said to be a sufficient plurality of persons with control of the media enterprises serving UK audiences. Yet on examination, the basis for this claim proves extremely thin. 1.3 Most fundamentally, the Provisional Findings fail to engage to any meaningful extent with the sufficiency of plurality. The concept of “sufficient plurality” is central to the public interest consideration at issue. An adverse public interest finding cannot be justified on the basis that a transaction may reduce plurality. The reduction must be of such a scale that plurality would become insufficient overall.