Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rebecca Swenson Dissertation March 27 2012 Ford Times FINAL

Brand Journalism: A Cultural History of Consumers, Citizens, and Community in Ford Times A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Rebecca Dean Swenson IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisor : Dr. John Eighmey March 2012 © Rebecca Dean Swenson 2012 Acknowledgements This dissertation would not have been completed without the assistance, support, love of many people. Thank you to my committee: Dr. John Eighmey, Dr. Mary Vavrus, Dr. Kathleen Hansen and Dr. Heather LaMarre for your input, wise guidance, and support. John Eighmey and Mary Vavrus, I am grateful for your encouragement and enthusiasm for my work from the kitchen (Betty Crocker Masters Thesis) to the garage (this dissertation on Ford.) You both cheered me on during my time in graduate school, and I always left our meetings feeling energized and ready the return to the project ahead. Kathy Hansen and Heather LaMarre both stepped in towards the end of this process. Thank you for your willingness to do so. Thank you to Dr. Albert Tims, who offered much support throughout the program and an open door for students. I appreciate all of the institutional support, including the Ralph Casey award, which allowed me to dedicate time to research and writing. Thank you to Dr. Hazel Dicken-Garcia for encouraging me to apply for the Ph.D. program, and to Dr. Jisu Huh and Sara Cannon, who very kindly helped me navigate a mountain of paperwork my last semester. Thank you to my fellow Murphy Hall graduate students for the encouragement, feedback, study dates, play dates, and fun. -

In Re Ford Motor Company Securities Litigation 00-CV-74233

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN SOUTHERN DIVISION Master C e No. 00-74233 In re FORD MOTOR CO. CLASS A TION SECURITIES LITIGATION The Honorable Avern Cohn DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL CONSOLIDATED COMPLAINT FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 l r" CJ'^ zti ^ OVERVIEW 1. This is an action on behalf of all purchasers of the common stock of Ford Motor Company, Inc. ("Ford") between March 31, 1998 and August 31, 2000 (the "Class Period"). This action arises out of the conduct of Ford to conceal from the investment community defects in Ford's Explorer sport-utility vehicles equipped with steel-belted radial ATX tires manufactured by Bridgestone Corp.'s U.S. subsidiary, Bridgestone/Firestone, Inc. ("Bridgestone/Firestone"). The Explorer is Ford's most important product and its largest selling vehicle, which has accounted for 25% of Ford's profits during the 1990s. Due to the success of the Explorer, Ford became Bridgestone/ Firestone's largest customer and sales of ATX tires have been the largest source of revenues and profits for Bridgestone/Firestone during the 1990s. During the Class Period, Ford and Bridgestone had knowledge ofthousands ofclaims for and complaints concerning ATX tire failures, especially ATX tires manufactured at Bridgestone/Firestone's Decatur, Illinois plant during and after a bitter 1994-1996 strike, due to design and manufacturing defects in, and under-inflation of, the tires, which, when combined with the unreasonably dangerous and unstable nature of the Explorer, resulted in over 2,200 rollover accidents, 400 serious injuries and 174 fatalities by 2000. -

UVA-BC-0145 FORD's E-BUSINESS STRATEGY in the Fall of 1999, Jacques Nasser, Ford Motor Company President and Chief Executive O

Graduate School of Business Administration UVA-BC-0145 University of Virginia FORD’S E-BUSINESS STRATEGY In the fall of 1999, Jacques Nasser, Ford Motor Company president and chief executive officer, announced a grand new vision for the firm: to become the “world’s leading consumer company providing automotive products and services.” Key to that dream was the transformation of the business using Web technologies. The company that taught the world how to mass- produce cars for the consumer market was going to become the leading e-business firm. Brian P. Kelly, Ford’s e-business vice president, described Ford’s plan to rebuild itself as a move to “consumercentric” from “dealercentric,” and stated that Ford would transform itself from being a “manufacturer to dealers” into a “marketer to consumers.” Our consumer-connect business has a totally integrated strategy to reach the consumer in conjunction with our dealers at every touch point. Ford continues to be at the forefront, integrating our global e-commerce activity from the consumer back through the entire supply chain, including linking our Customer Assistance Centers and in-vehicle communications.1 New Web sites were launched for buyers and owners. In-car computer and communications services were announced that would bring travel, security, entertainment, and Web access to the motorist and an electronic connection between consumers and the Ford Motor Company. In February, the company announced it was purchasing Internet PCs for all employees, “to reach its vision of being on the leading edge of technology and connect more closely with its customers.” In March 2000, the company announced the creation of a business- to-business integrated supplier exchange through a single global portal, a joint venture with GM and DaimlerChrysler to create the world’s largest virtual marketplace. -

Important Notice

IMPORTANT NOTICE THIS OFFERING IS AVAILABLE ONLY TO INVESTORS WHO ARE NON-U.S. PERSONS (AS DEFINED IN REGULATION S UNDER THE UNITED STATES SECURITIES ACT OF 1933 (THE “SECURITIES ACT”) (“REGULATION S”)) LOCATED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. IMPORTANT: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the attached document (the “document”) and you are therefore advised to read this carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the document. In accessing the document, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them any time you receive any information from Sky plc (formerly known as British Sky Broadcasting Group plc) (the “Issuer”), Sky Group Finance plc (formerly known as BSkyB Finance UK plc), Sky UK Limited (formerly known as British Sky Broadcasting Limited), Sky Subscribers Services Limited or Sky Telecommunications Services Limited (formerly known as BSkyB Telecommunications Services Limited) (together, the “Guarantors”) or Barclays Bank PLC or Société Générale (together, the “Joint Lead Managers”) as a result of such access. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE IN THE UNITED STATES OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE SECURITIES AND THE GUARANTEES HAVE NOT BEEN, AND WILL NOT BE, REGISTERED UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT, OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OF THE UNITED STATES OR OTHER JURISDICTION AND THE SECURITIES AND THE GUARANTEES MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, WITHIN THE UNITED STATES OR TO, OR FOR THE ACCOUNT OR BENEFIT OF, U.S. -

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All Rights Reserved

Public Citizen Copyright © 2016 by Public Citizen Foundation All rights reserved. Public Citizen Foundation 1600 20th St. NW Washington, D.C. 20009 www.citizen.org ISBN: 978-1-58231-099-2 Doyle Printing, 2016 Printed in the United States of America PUBLIC CITIZEN THE SENTINEL OF DEMOCRACY CONTENTS Preface: The Biggest Get ...................................................................7 Introduction ....................................................................................11 1 Nader’s Raiders for the Lost Democracy....................................... 15 2 Tools for Attack on All Fronts.......................................................29 3 Creating a Healthy Democracy .....................................................43 4 Seeking Justice, Setting Precedents ..............................................61 5 The Race for Auto Safety ..............................................................89 6 Money and Politics: Making Government Accountable ..............113 7 Citizen Safeguards Under Siege: Regulatory Backlash ................155 8 The Phony “Lawsuit Crisis” .........................................................173 9 Saving Your Energy .................................................................... 197 10 Going Global ...............................................................................231 11 The Fifth Branch of Government................................................ 261 Appendix ......................................................................................271 Acknowledgments ........................................................................289 -

Vote Summary Report Reporting Period: 10/01/2017 to 12/31/2017

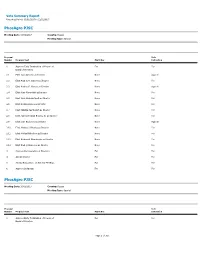

Vote Summary Report Reporting Period: 10/01/2017 to 12/31/2017 PhosAgro PJSC Meeting Date: 10/02/2017 Country: Russia Meeting Type: Special Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Early Termination of Powers of For For Board of Directors 2.1 Elect Igor Antoshin as Director None Against 2.2 Elect Andrey A. Guryev as Director None For 2.3 Elect Andrey G. Guryev as Director None Against 2.4 Elect Yury Krugovykh as Director None For 2.5 Elect Sven Ombudstvedt as Director None For 2.6 Elect Roman Osipov as Director None For 2.7 Elect Natalya Pashkevich as Director None For 2.8 Elect James Beeland Rogers, Jr. as Director None For 2.9 Elect Ivan Rodionov as Director None Against 2.10 Elect Marcus J. Rhodes as Director None For 2.11 Elect Mikhail Rybnikov as Director None For 2.12 Elect Aleksandr Sharabayko as Director None For 2.13 Elect Andrey Sharonov as Director None For 3 Approve Remuneration of Directors For For 4 Amend Charter For For 5 Amend Regulations on General Meetings For For 6 Approve Dividends For For PhosAgro PJSC Meeting Date: 10/02/2017 Country: Russia Meeting Type: Special Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Mgmt Rec Instruction 1 Approve Early Termination of Powers of For For Board of Directors Page 1 of 767 Vote Summary Report Reporting Period: 10/01/2017 to 12/31/2017 PhosAgro PJSC Proposal Vote Number Proposal Text Mgmt Rec Instruction 2.1 Elect Igor Antoshin as Director None Against 2.2 Elect Andrey A. -

2010 BHP Billiton Summary Review

In this Summary Review People and Safety Our results at a glance Karen Wood describes our commitment to our people A snapshot of our results and five-year financial summary and safety, including our approach to leadership See page 2 See page 24 Chairman’s Review – Environment and Communities Our strategy delivers The way we manage our responsibilities to the An overview of the year by Jacques Nasser AO environment and communities in which we operate See page 4 is explained by J Michael Yeager See page 26 Chief Executive Officer’s Report – An unchanged strategy Board of Directors The year in review, by Marius Kloppers The profiles of BHP Billiton’s Directors See page 6 See page 28 Customer Sector Groups Group Management Committee An update from each of our Customer Sector Groups, Profiles of the senior management team at BHP Billiton providing a snapshot of BHP Billiton’s operational performance See page 31 See page 13 Corporate Governance Summary Finance and Marketing overview A summary of BHP Billiton governance An outline of our financial position from Alex Vanselow and See page 32 an update on our marketing operations by Alberto Calderon Remuneration Summary See page 20 Key policy principles and information about Performance update of our operations our remuneration Details of key achievements in Ferrous and Coal See page 34 by Marcus Randolph and highlights of the year Shareholder information in Non-Ferrous by Andrew Mackenzie Key dates and information relevant for shareholders, See page 22 including our dividend policy and payments See page 36 Corporate Directory A list of major BHP Billiton offices and share registries See Inside Back Cover This Summary Review is designed to provide you with an update on This Summary Review is not a substitute for the Annual Report 2010 the operations and performance of BHP Billiton over the year ended and does not contain all the information needed to give as full an 30 June 2010 in a concise and easy-to-read format. -

UAW Vice-President's Office: Donald Ephlin Records

UAW Vice-President’s Office: Don Ephlin Records 52 linear feet 1960s-2000, bulk 1970s-1980s Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI Finding aid written by Maureen Simari & Aimee Ergas on January 11, 2011. Accession Number: LR001404 Creator: Donald F. Ephlin Acquisition: The records of the UAW Vice-President’s Office from Don Ephlin’s tenure were deposited at the Reuther Library in 1989, 1990, and 1994. Language: Material entirely in English. Access: Collection is open for research. Use: Refer to the Walter P. Reuther Library Rules for Use of Archival Materials. Restrictions: Researchers may encounter records of a sensitive nature – personnel files, case records and those involving investigations, legal and other private matters. Privacy laws and restrictions imposed by the Library prohibit the use of names and other personal information, which might identify an individual, except with written permission from the Director and/or the donor. Notes: Citation style: “UAW Vice-President’s Office: Don Ephlin Records, Box [#], Folder [#], Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University” Related Material: Two boxes of audiotapes, videotapes, photographs and other A-V material were transferred to the Reuther’s Audiovisual Department (Box 51-52). Related books and serials can be found in the Reuther’s Library Collection. PLEASE NOTE: Material in this collection has been arranged by series ONLY. Folders are not arranged within each series – we have provided an inventory based on their original order. Subjects may be dispersed throughout several boxes within any given series. History Donald F. Ephlin became active in the UAW at the General Motors Assembly Plant in Framingham, MA in the late 1940s, before joining the International Union staff in 1960 as a member of the GM and Aerospace Departments. -

Starring Matt Damon and Christian Bale)

SEPTEMBER 2019 a The 6 Questions All Good Stories Must Answer (Starring Matt Damon and Christian Bale) I have a confession to make: I'm hooked on trailers - and not the kind you hitch to your car or truck. It's probably because I love going to the movies, and a well-made trailer is a tantalizing taste of pleasure soon to come. It occurred to me recently, however, that a movie trailer could also be a useful tool when it comes to teaching storytelling. Think about it: at its essence a trailer is designed to sell you a story, and it has 2-3 minutes (in theaters) or 30-60 seconds (on TV) to convince you it's a good story. What defines a good story? There are numerous elements that contribute to any story's success, but one yardstick to measure that success is to ask how well the story answers six questions that the audience, whether they are consciously aware of it or not, will definitely ask: 1. Who is the story about? 2. What do they want? 3. What stands in their way that makes the pursuit interesting? 4. How do they respond to those barriers or obstacles? 5. What happens in the end? 6. What does it mean? I was reminded of these essential questions last week when I saw the trailer for "Ford v. Ferrari," a feature film starring Matt Damon and Christian Bale due in theaters this November. Based on a true story, the movie follows Damon and Bale (portraying auto racing legends Carroll Shelby and Ken Miles, respectively) as they try to win the legendary 24 Hours of Le Mans. -

THE COLLECTION of MRS. HENRY FORD II New York & London

PRESS RELEASE | NEW YORK | L O N D O N I FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE : 8 FEBRUARY 2021 THE COLLECTION OF MRS. HENRY FORD II New York & London Palm Beach: 30 March, Christie’s New York – Live Eaton Square and Turville Grange: 15 April, Christie’s London – Live Eaton Square, London, England Palm Beach, Florida, USA Turville Grange, Buckinghamshire, England Christie’s announces the principal Collection of Mrs. Henry Ford II, to be offered across two live sales in New York and London this spring. Part I of The Collection of Mrs. Henry Ford II, from her Palm Beach home, will be offered in a live sale at Christie’s New York on 30 March followed by Part II, from her English residences in London’s prestigious Eaton Square and her country home, Turville Grange in Buckinghamshire, to be offered at Christie’s London on 15 April. The New York and London collection sales build on the strong momentum established by the highly successful sales of Mrs. Henry Ford II’s important Impressionist paintings and jewelry at Christie’s New York last December, with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Pierreuse, achieving the top price of the 20th Century Sale: Hong Kong to New York. The collection of Mrs. Henry Ford II to be offered this spring, comprises approximately 650 lots and is expected to realize in excess of $5 million across both the New York and London auctions. Highlights of the collection include important impressionist works as well as masterpieces of the decorative arts from the celebrated interiors created by McMillen for Henry Ford II at Grosse Pointe, Michigan in the 1950s; the collection there was considered almost without rival in its own time. -

Research Center New and Unprocessed Archival Accessions

NEW AND UNPROCESSED ARCHIVAL ACCESSIONS List Published: April 2020 Benson Ford Research Center The Henry Ford 20900 Oakwood Boulevard ∙ Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 USA [email protected] ∙ www.thehenryford.org New and Unprocessed Archival Accessions April 2020 OVERVIEW The Benson Ford Research Center, home to the Archives of The Henry Ford, holds more than 3000 individual collections, or accessions. Many of these accessions remain partially or completely unprocessed and do not have detailed finding aids. In order to provide a measure of insight into these materials, the Archives has assembled this listing of new and unprocessed accessions. Accessions are listed alphabetically by title in two groups: New Accessions contains materials acquired 2018-2020, and Accessions 1929-2017 contains materials acquired since the opening of The Henry Ford in 1929 through 2017. The list will be updated periodically to include new acquisitions and remove those that have been more fully described. Researchers interested in access to any of the collections listed here should contact Benson Ford Research Center staff (email: [email protected]) to discuss collection availability. ACCESSION NUMBERS Each accession is assigned a unique identification number, or accession number. These are generally multi-part codes, with the left-most digits indicating the year in which the accession was acquired by the Archives. There, are however, some exceptions. Numbering practices covering the majority of accessions are outlined below. - Acquisitions made during or after the year 2000 have 4-digit year values, such as 2020, 2019, etc. - Acquisitions made prior to the year 2000 have 2-digit year values, such as 99 for 1999, 57 for 1957, and so forth. -

Ford) Compared with Japanese

A MAJOR STUDY OF AMERICAN (FORD) COMPARED WITH JAPANESE (HONDA) AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY – THEIR STRATEGIES AFFECTING SURVIABILTY PATRICK F. CALLIHAN Bachelor of Engineering in Material Science Youngstown State University June 1993 Master of Science in Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering Youngstown State University March 2000 Submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF ENGINEERING at the CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY AUGUST, 2010 This Dissertation has been approved for the Department of MECHANICAL ENGINEERING and the College of Graduate Studies by Dr. L. Ken Keys, Dissertation Committee Chairperson Date Department of Mechanical Engineering Dr. Paul A. Bosela Date Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Dr. Bahman Ghorashi Date Department of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering Dean of Fenn College of Engineering Dr. Chien-Hua Lin Date Department Computer and Information Science Dr. Hanz Richter Date Department of Mechanical Engineering ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First I would like to express my sincere appreciation to Dr. Keys, my advisor, for spending so much time with me and providing me with such valuable experience and guidance. I would like to thank each of my committee members for their participation: Dr. Paul Bosela, Dr. Baham Ghorashi, Dr. Chien-Hua Lin and Dr. Hanz Richter. I want to especially thank my wife, Kimberly and two sons, Jacob and Nicholas, for the sacrifice they gave during my efforts. A MAJOR STUDY OF AMERICAN (FORD) COMPARED WITH JAPANESE (HONDA) AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY – THEIR STRATEGIES AFFECTING SURVIABILTY PATRICK F. CALLIHAN ABSTRACT Understanding the role of technology, in the automotive industry, is necessary for the development, implementation, service and disposal of such technology, from a complete integrated system life cycle approach, to assure long-term success.