Transportation: Past, Present and Future “From the Curators”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valley & Spruce Project Initial Study and Mitigated

VALLEY & SPRUCE PROJECT INITIAL STUDY AND MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION Prepared for: City of Rialto December 2017 VALLEY & SPRUCE PROJECT INITIAL STUDY AND MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION Prepared For: City of Rialto 150 S. Palm Avenue Rialto, CA 92376 Prepared By: Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. 401 B Street, Suite 600 San Diego, California 92101 December 2017 095894012 Copyright © 2017 Kimley-Horn and Associates, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Initial Study ............................................................................................................................................ 1 II. Description of Proposed Project ........................................................................................................... 2 III. Required Permits ................................................................................................................................... 8 IV. Environmental Factors Potentially Affected ......................................................................................... 9 V. Determination ........................................................................................................................................ 9 VI. Environmental Evaluation .................................................................................................................. 10 1. Aesthetics ................................................................................................................................ 10 2. Agricultural and Forestry Resources ..................................................................................... -

2016 Alpine Lenkradinterface Online

Alpine Electronics GmbH Wilhelm-Wagenfeld-Str. 1-3 D-80807 München Tel.: 089 2444 31 888 [email protected] - www.alpine.de Zünd- Rück- Anschluss- Telefon Speedpu Hand- Annehmen ung Dim-mer wärts- Marke Model Baujahr Original verbaute Headunit Adapter lse bremse typ Auflegen (ACC) gang Alfa 147 2000 - Blaupunkt Mid / High APF-S101AR Mini-ISO No Car Car No No No Alfa 156 2000 - Blaupunkt Mid / High APF-S101AR Mini-ISO No Car Car No No No Alfa GT 2004 - Blaupunkt Mid / High APF-S101AR Mini-ISO No Car Car No No No Alfa 159 2005 - Blaupunkt APF-S102AR Mini-ISO Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Alfa Brera 2006 - Blaupunkt APF-S102AR Mini-ISO Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Alfa Spider 2007 - Blaupunkt APF-S102AR Mini-ISO Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Alfa 147 2003 - Blaupunkt APF-S103AR Mini-ISO No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Alfa Giulietta 2010 - Blaupunkt APF-S104AR Mini-ISO Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Alfa MiTo 2008 - Blaupunkt APF-S104AR Mini-ISO Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Alfa Giulietta 2014 - APF-S106AR Mini-ISO Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Alfa MiTo 2014 - APF-S106AR Mini-ISO Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Audi A3 1996 - 2003 Concert / Symphony APF-S100AU Mini-ISO No Car Car No No No Audi A4 1995 - 2004 Chorus / Blaupunkt APF-S100AU Mini-ISO No Car Car No No No Audi A6 1997 - 2004 Matsushita / Grundig APF-S100AU Mini-ISO No Car Car No No No Audi TT 1999 - 2005 Matsushita / Grundig APF-S100AU Mini-ISO No Car Car No No No Audi A2 (8Z) 1999 - 2005 with "removable" OEM-HU, with CAN-Bus, without MMI APF-S101AU Mini-ISO / 40-way No Yes Yes Yes Yes No Audi A3 (8P) 05/2003 - 2013 with "removable" -

Brian Mcmahon Chad Roberts, Roxanne Sands, James A

RAMSEY COUNTY “Abide with Me” Grace Craig Stork, 1916 Rebecca A. Ebnet-Mavencamp —Page 10 HıstoryA Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society Fall 2016 Volume 51, Number 3 A Workplace Accident John Anderson’s Fall from the High Bridge John T. Sielaff, page 3 Towering above the Mississippi River flood plain, St. Paul’s Smith Avenue High Bridge, seen here in a 1905 postcard, connected the city’s oldest residential neighborhood, West Seventh Street, with its newest at the time, Cherokee Heights, or the Upper West Side. John Anderson, a painter working on the bridge in 1902, fell and survived the accident. His story tells us much about the dangers in the workplace then and now. Photo by the Detroit Photographic Company, courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY RAMSEY COUNTY President Chad Roberts Founding Editor (1964–2006) Virginia Brainard Kunz Editor Hıstory John M. Lindley Volume 51, Number 3 Fall 2016 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE MISSION STATEMENT OF THE RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ON JANUARY 25, 2016: James Miller Preserving our past, informing our present, inspiring our future Chair Jo Anne Driscoll First Vice Chair Carl Kuhrmeyer C O N T E N T S Second Vice Chair Susan McNeely 3 A Workplace Accident Secretary Kenneth H. Johnson John Anderson’s Fall from the High Bridge Treasurer John T. Sielaff William B. Frels Immediate Past Chair 10 “Abide with Me” Anne Cowie, Cheryl Dickson, Mari Oyanagi Grace Craig Stork, 1916 Eggum, Thomas Fabel, Martin Fallon, Rebecca A. -

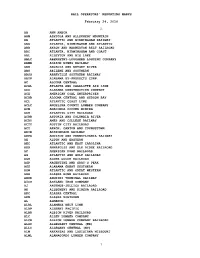

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 a AA

RAIL OPERATORS' REPORTING MARKS February 24, 2010 A AA ANN ARBOR AAM ASHTOLA AND ALLEGHENY MOUNTAIN AB ATLANTIC AND BIRMINGHAM RAILWAY ABA ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND ATLANTIC ABB AKRON AND BARBERTON BELT RAILROAD ABC ATLANTA, BIRMINGHAM AND COAST ABL ALLEYTON AND BIG LAKE ABLC ABERNETHY-LOUGHEED LOGGING COMPANY ABMR ALBION MINES RAILWAY ABR ARCADIA AND BETSEY RIVER ABS ABILENE AND SOUTHERN ABSO ABBEVILLE SOUTHERN RAILWAY ABYP ALABAMA BY-PRODUCTS CORP. AC ALGOMA CENTRAL ACAL ATLANTA AND CHARLOTTE AIR LINE ACC ALABAMA CONSTRUCTION COMPANY ACE AMERICAN COAL ENTERPRISES ACHB ALGOMA CENTRAL AND HUDSON BAY ACL ATLANTIC COAST LINE ACLC ANGELINA COUNTY LUMBER COMPANY ACM ANACONDA COPPER MINING ACR ATLANTIC CITY RAILROAD ACRR ASTORIA AND COLUMBIA RIVER ACRY AMES AND COLLEGE RAILWAY ACTY AUSTIN CITY RAILROAD ACY AKRON, CANTON AND YOUNGSTOWN ADIR ADIRONDACK RAILWAY ADPA ADDISON AND PENNSYLVANIA RAILWAY AE ALTON AND EASTERN AEC ATLANTIC AND EAST CAROLINA AER ANNAPOLIS AND ELK RIDGE RAILROAD AF AMERICAN FORK RAILROAD AG ATLANTIC AND GULF RAILROAD AGR ALDER GULCH RAILROAD AGP ARGENTINE AND GRAY'S PEAK AGS ALABAMA GREAT SOUTHERN AGW ATLANTIC AND GREAT WESTERN AHR ALASKA HOME RAILROAD AHUK AHUKINI TERMINAL RAILWAY AICO ASHLAND IRON COMPANY AJ ARTEMUS-JELLICO RAILROAD AK ALLEGHENY AND KINZUA RAILROAD AKC ALASKA CENTRAL AKN ALASKA NORTHERN AL ALMANOR ALBL ALAMEDA BELT LINE ALBP ALBERNI PACIFIC ALBR ALBION RIVER RAILROAD ALC ALLEN LUMBER COMPANY ALCR ALBION LUMBER COMPANY RAILROAD ALGC ALLEGHANY CENTRAL (MD) ALLC ALLEGANY CENTRAL (NY) ALM ARKANSAS AND LOUISIANA -

Custom Imprint

CUSTOM IMPRINT TO CREATE A COMPREHENSIVE PROMOTIONAL PROGRAM SpecCast is a leading manufacturer of quality die-cast metal, fine pewter and resin collectibles. We have over 30 years experience in providing the best quality products and services to our customers. Our goal is to build a long-term relationship and create a successful promotional program, that you, the customer, will be satisfied and confident in doing business with us. Send us your logo, we can do the rest! We will duplicate corporate or organizational logos to you exact specifications. Our highly creative and experienced graphic artists can also create the images you want to convey. Our quality collectibles are great for: Premiums and Promotions - For customer appreciation, employee gifts and incentives. Event Marketing - For new store openings, new product introductions and special events or anniversaries. Retail Programs - Help increase store traffic, build brand recognition and customer loyalty. Perfect for businesses of all sizes! The SpecCast Custom Imprint Program offers quality variations to choose from. We now offer the lowest minimums in the industry. For as little as 48 units, you can have a customized collectible. Call us at 1-800-844-8067 ext 252 or e-mail [email protected] for a free quote! 1 WANT A REPLICA OF AN ITEM IN YOUR CUSTOMER’S PRODUCT LINE? We can replicate any item by developing a custom tool to replicate this item with several options for material, and suggestions for the size/scale. Working from specifications that you would provide, our design team will review and provide a quote for both the new tool and the unit cost, then once approved, a CAD design of the new mold will be provided; once the CAD is approved, a model will be made for review/approval and then production of tooling and the actual replicas will begin. -

TORRANCE HERALD Twonfy.Thrsef Wunlocl Tjtomomi.KS, for Sale Trucks, Truck*, Etc

MISCELLANEOUS 9S HO AUTOMOBILES, AUTOMOBILES. 112 112 \UTOMOBILES, IK AUTOMOBILES. 112 \UTOMOBII,ES, 112 ANUARV 29, 1953 TORRANCE HERALD Twonfy.Thrsef Wunlocl tJTOMOmi.KS, For Sale Trucks, Truck*, Etc. Trucks, Etc. Truck*. Etc. AUTOMOBILES. 112 AUTOMOBILES, \U CASH 1 FILL. DIRT McCdllum Buick \You'll Be Proud to Sing WRECKED, ntlRNMD. AND A-l Month End FOR SALE 'You Belor g to Me' TRANSPORTATION VERMONT Auto Wreckers In A Ca r From We Load 2264ft 80. Vermont SPECIALS Torrance 3895 LOT CLEARANCE SALE CARS FOLEY RANCH 1949 FORD Club Coupe OUR WANTED Custom model with radio 3401 Spencer St. 1951 DODGE CORONET 1951 PLYMOUTH Belve These Cars CARS end TRUCKS and heater. Refinished in Torranct 4-Dopr Sedan. Radio, dere. Radio, heater, 2 TO WRECK Terrace Green Clearance Sale beautiful heater and gyromatic tone finish, like new MUST BE SOLD matching custom MIKE McMANUS with new transmission. Nice. thloughout. MIMEOCIHAPH mnchlne. Rtcel- seat covers. lont condition. Will print post Terminal 40317 BUY with CONFIDENCE OWN with PRIDE Choice cardu. Vie. Iltunnable. $1125 $1895 $1895 Your Phorto Torrance 2032 1951 PJBNTIAC 8 CONVERTIBLE. ........... .$2295 in 20 VOLUME encyclopedia jet, TRAILERS 1948 CHEVROLET y2 -ton 1950 CHEVROLET Club 1950 .MERCURY 4-Door DeluZS nrodel with even- nerwory. Including hvdrn- American P(<oplr»' 19111 year matlc. General Premium Una. Just aold In W&. 10,000 «>nk, with hoohcale. All JI20. For Sain or Trade Panel. Refinished in Pacific Coupe, Radio and Sedan. Overdrive, seat covers. In' fine $195. ' 12-FT. Sportsman House Trailer. blue, chrome work perfect, heater, whitewalls. A Hound-up ['OIITABLB Western Heal buy. -

Liicycle PARADE L'abbing Ihkougil PARK PLAZA Fnlkancl THIRTY-FIFTH

-- -- liICYCLE PARADE l'AbbING IHKOUGIl PARK PLAZA FNlKANCl THIRTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE CITY OF BROOKLYN AND THE FIRST OF THE COUNTY OF KINGS FOR THE YEAR 1895 BROOKLYN PRINTED FOR THE COMMISSIONER THE OFFICIAL LIST. Commissioner, FRANK SQUIER. Deputy Commissioner, HENRY L. PALMER. Secretary, JOHN EDWARD SMITII, General Superintendent, RUDOLPH ULRICH. Landscape Architects, Advisory, OLMSTED, OLMSTED & ELIOT. Paymaster, ROBERT H. SMITH. Assistant Paymaster, OSCAR C. WHEDON. Property and Labor Clerk, WILLIAM A. BOOTH. Stenographer, MAY G. HAMILTON. THECOMMISSIONER~S REPORT OF THE WORK OF THE DURINGTHE YEAR 1895. OFIJICE OF THE COMMISSIONEROF THE DEPARTMENTOF PARKS, " LITCHFIELD MANSION,"PROSPECT PARK, BROOI~LYN,January st, 1896. To the Honorable, the Common Council : GENTLEMEN-I have the honor herewith to submit to your Honorable Body my Annual Report concerning the care of the Parks and Parkways of the City of Brooklyn and of the County of Kings, which have been under my charge during the year 1895. There have been more than the usual developments in the way of care and improvement of the parks, and in addition there has been an acquisition of property which doubles the area of park lands existing at the beginning of the year, thus placing the city somewhat on a par with other great cities of the country. Steps have also been taken in the direction of increas- ing the pleasure drives, and the County now owns nearly all the property needed for the creation of the most charming drive in the world-the Hay Ridge Parkway, or, as it is popularly called, the Shore Drive. -

MCO Arrival Wayfnding Map

MCO Arrival Wayfnding Map N SIDE Gates 1-29 Level 1 Gates 100-129 Ground Transportation & Baggage Claim (8A) Level 2 Baggage Claim Gates 10-19 Gates Ticketing Locations 20-29 Gates 100-111 A-1 A-2 Level 3 A-3 A-4 2 1 Gates Gates 1-9 112-129 Hyatt Regency - Lvl.4 - Lvl.4 Regency Hyatt Security Checkpoint To Gates 70 - 129 70 Gates To Food Court To Gates 1-59 1-59 Gates To Security Checkpoint Gates 70-79 Gates 50-59 To Parking “C” Gates 3 90-99 4 B-1 B-2 Level 3 B-3 B-4 Gates Gates 30-39 Ticketing Locations Gates 80-89 40-49 Gates 70-99 Level 2 Gates 30-59 Baggage Claim Level 1 Ground Transportation & Baggage Claim (28B) SIDE C Check-in and baggage claim locations subject to change. Please check signage on arrival. *Map not to scale Find it ALL in One Place Welcome to Orlando Download the Orlando MCO App Available for International Airport (MCO) OrlandoAirports.net /flymco @MCO @flymco Flight Arrival Guide 03/18 To reach the Main Terminal, The journey to the To retrieve checked baggage, take follow directions on the overhead Main Terminal (A-Side or B-Side) the stairs, escalator or elevator down signage to the shuttle station 2 takes just over one minute. As the 4 6 to the Arrivals/Baggage Claim on which is located in the center train transports you, observe the Level 2. Check the monitors to of the Airside Terminal. signage and listen to the instructions determine the correct carousel directing you to either Baggage Claim A for your flight. -

TIMES MAGAZINE for EARLY FORD ENTHUSIASTS an International Organization Volume 57, Number 6 November/December 2020

TIMES MAGAZINE FOR EARLY FORD ENTHUSIASTS An International Organization Volume 57, Number 6 November/December 2020 1934 Standard Fordor Sedan An International Organization Copyright @ The Early Ford V-8 Club, 2020 P.O. Box 1715 Maple Grove, MN 55311 Volume 57 Number 6 November/December 2020 Contributions of material for publication in the V-8 TIMES are gratefully accepted. It will be assumed they are donated unless other arrangements are made. CONTENTS Inside Departments... From the Oval Office .............................................................................. 1 From the Editor ...................................................................................... 2 Letters ...................................................................................................... 3 Reader’s Reply ........................................................................................ 7 In Transit. ................................................................................................ 11 Early Ford V-8 Foundation .................................................................... 17 Regional Group News ............................................................................. 83 CARrespondence (Tech Advisors) ......................................................... 95 Page 21 Classified Ads ........................................................................................ 103 Features... Opinion .....................................................................................................15 Ford Notes: -

GOOGLE LLC V. ORACLE AMERICA, INC

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus GOOGLE LLC v. ORACLE AMERICA, INC. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT No. 18–956. Argued October 7, 2020—Decided April 5, 2021 Oracle America, Inc., owns a copyright in Java SE, a computer platform that uses the popular Java computer programming language. In 2005, Google acquired Android and sought to build a new software platform for mobile devices. To allow the millions of programmers familiar with the Java programming language to work with its new Android plat- form, Google copied roughly 11,500 lines of code from the Java SE pro- gram. The copied lines are part of a tool called an Application Pro- gramming Interface (API). An API allows programmers to call upon prewritten computing tasks for use in their own programs. Over the course of protracted litigation, the lower courts have considered (1) whether Java SE’s owner could copyright the copied lines from the API, and (2) if so, whether Google’s copying constituted a permissible “fair use” of that material freeing Google from copyright liability. In the proceedings below, the Federal Circuit held that the copied lines are copyrightable. -

2019 Cruisin Nationals Santa Maria, Ca

2019 Cruisin Nationals Santa Maria, Ca Rich Pichette Memorial Award Award to a person or persons for their achievements, dedication and contributions to the kustom car hobby. David Aguilar Chula Vista, CA Top 5 Wild Kustoms George Garcia Bellflower, CA 1958 Ford Ranchero Ray Silva Sun City, CA 1935 Ford Cherie Zocchi Walnut Creek, CA 1950 Mercury Chris Martinez Albuquerque, New Mexico 1951 Chevy Tony Wood Valley Village, CA 1967 Ford Wagon Top 5 Mild Kustoms Todd Nichols / Gambino San Jose, CA 1963 Ford T Bird Eckerts Rod & Custom Molalla, WA 1949 Hudson Pete De Leon Beaumont, CA 1950 Mercury Andy Sapien Hacienda Heights, CA 1950 Chevy Fleetline Nick Dias Chula Vista, CA 1950 Chevy Convertible Top 3 Early Kustoms Richard Metter Santee, CA 1940 Mercury Scott Gillen Malibu, CA 1936 Ford Coupe Steve Pierce Napa, CA 1940 Buick Top 2 Early Hot Rods Gary Miller Castro Valley, CA 1934 Ford Pickup Art Serna Lindsay, CA 1929 Ford Pickup Top 2 Under Construction Roger Castillo Mission Hills, CA 1938 Ford Carlos Andrede Chula Vista, CA 1939 Cadillac Top 2 Commercial Pepper Sanchez Tulare, CA 1955 Chevy Pickup Guy Garza Fontana, CA 1948 Chevy Suburban George Barris Family Award For Outstanding Custom Alex Gambino San Jose, CA 1963 Ford T Bird John D’Agostino Kustom Award of Excellence Steve Pierce Napa, CA 1940 Buick Mayor of Santa Maria Award Carly Brogren Monroe, WA 1939 Lincoln Zephyr Santa Maria City Counsel Award Sergio Edell Oakland, CA 1940 Ford Coupe Santa Maria Chamber Of Commerce Visitors & Convention Bureau Award Tom Pessagno Castaic, CA 1964 Buick Riviera Gene Winfield Award For Outstanding Custom John Deollos South Jordon, UT 1954 Ford Ranch Wagon Larry Watson Award Jeff Myers Arkansas City, Kansas 1957 Ford Ranchero Bill Hines Award Alvin Garnica San Jose, CA 1951 Chevy Satan Angels C.C. -

The Rise of Mobility As a Service Reshaping How Urbanites Get Around

Issue 20 | 2017 Complimentary article reprint The rise of mobility as a service Reshaping how urbanites get around By Warwick Goodall, Tiffany Dovey Fishman, Justine Bornstein, and Brett Bonthron Illustration by Traci Daberko Breakthroughs in self-driving cars are only the beginning: The entire way we travel from point A to point B is changing, creating a new ecosystem of personal mobility. The shift will likely affect far more than transportation and automakers—industries from insurance and health care to energy and media should reconsider how they create value in this emerging environment. Deloitte offers a suite of services to help clients tackle Future of Mobility- related challenges, including setting strategic direction, planning operating models, and implementing new operations and capabilities. Our wide array of expertise allows us to become a true partner throughout an organization’s comprehensive, multidimensional journey of transformation. About Deloitte Deloitte refers to one or more of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, a UK private company limited by guarantee, and its network of member firms, each of which is a legally separate and independent entity. Please see http://www/deloitte.com/about for a detailed description of the legal structure of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited and its member firms. Please see http://www.deloitte.com/us/about for a detailed description of the legal structure of the US member firms of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited and their respective subsidiaries. Certain services may not be available to attest clients under the rules and regulations of public accounting. Deloitte provides audit, tax, consulting, and financial advisory services to public and private clients spanning multiple industries.