The Numinous in Gothic and Post-Gothic Ghost Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extraterrestrial Places in the Cthulhu Mythos

Extraterrestrial places in the Cthulhu Mythos 1.1 Abbith A planet that revolves around seven stars beyond Xoth. It is inhabited by metallic brains, wise with the ultimate se- crets of the universe. According to Friedrich von Junzt’s Unaussprechlichen Kulten, Nyarlathotep dwells or is im- prisoned on this world (though other legends differ in this regard). 1.2 Aldebaran Aldebaran is the star of the Great Old One Hastur. 1.3 Algol Double star mentioned by H.P. Lovecraft as sidereal The double star Algol. This infrared imagery comes from the place of a demonic shining entity made of light.[1] The CHARA array. same star is also described in other Mythos stories as a planetary system host (See Ymar). The following fictional celestial bodies figure promi- nently in the Cthulhu Mythos stories of H. P. Lovecraft and other writers. Many of these astronomical bodies 1.4 Arcturus have parallels in the real universe, but are often renamed in the mythos and given fictitious characteristics. In ad- Arcturus is the star from which came Zhar and his “twin” dition to the celestial places created by Lovecraft, the Lloigor. Also Nyogtha is related to this star. mythos draws from a number of other sources, includ- ing the works of August Derleth, Ramsey Campbell, Lin Carter, Brian Lumley, and Clark Ashton Smith. 2 B Overview: 2.1 Bel-Yarnak • Name. The name of the celestial body appears first. See Yarnak. • Description. A brief description follows. • References. Lastly, the stories in which the celes- 3 C tial body makes a significant appearance or other- wise receives important mention appear below the description. -

Natural Selection and Coalescent Theory

Natural Selection and Coalescent Theory John Wakeley Harvard University INTRODUCTION The story of population genetics begins with the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species and the tension which followed concerning the nature of inheritance. Today, workers in this field aim to understand the forces that produce and maintain genetic variation within and between species. For this we use the most direct kind of genetic data: DNA sequences, even entire genomes. Our “Great Obsession” with explaining genetic variation (Gillespie, 2004a) can be traced back to Darwin’s recognition that natural selection can occur only if individuals of a species vary, and this variation is heritable. Darwin might have been surprised that the importance of natural selection in shaping variation at the molecular level would be de-emphasized, beginning in the late 1960s, by scientists who readily accepted the fact and importance of his theory (Kimura, 1983). The motivation behind this chapter is the possible demise of this Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution, which a growing number of population geneticists feel must follow recent observations of genetic variation within and between species. One hundred fifty years after the publication of the Origin, we are struggling to fully incorporate natural selection into the modern, genealogical models of population genetics. The main goal of this chapter is to present the mathematical models that have been used to describe the effects of positive selective sweeps on genetic variation, as mediated by gene genealogies, or coalescent trees. Background material, comprised of population genetic theory and simulation results, is provided in order to facilitate an understanding of these models. -

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball. -

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: the Fiction

Errata for H. P. Lovecraft: The Fiction The layout of the stories – specifically, the fact that the first line is printed in all capitals – has some drawbacks. In most cases, it doesn’t matter, but in “A Reminiscence of Dr. Samuel Johnson”, there is no way of telling that “Privilege” and “Reminiscence” are spelled with capitals. THE BEAST IN THE CAVE A REMINISCENCE OF DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON 2.39-3.1: advanced, and the animal] advanced, 28.10: THE PRIVILEGE OF REMINISCENCE, the animal HOWEVER] THE PRIVILEGE OF 5.12: wondered if the unnatural quality] REMINISCENCE, HOWEVER wondered if this unnatural quality 28.12: occurrences of History and the] occurrences of History, and the THE ALCHEMIST 28.20: whose famous personages I was] whose 6.5: Comtes de C——“), and] Comtes de C— famous Personages I was —”), and 28.22: of August 1690 (or] of August, 1690 (or 6.14: stronghold for he proud] stronghold for 28.32: appear in print.”), and] appear in the proud Print.”), and 6.24: stones of he walls,] stones of the walls, 28.34: Juvenal, intituled “London,” by] 7.1: died at birth,] died at my birth, Juvenal, intitul’d “London,” by 7.1-2: servitor, and old and trusted] servitor, an 29.29: Poems, Mr. Johnson said:] Poems, Mr. old and trusted Johnson said: 7.33: which he had said had for] which he said 30.24: speaking for Davy when others] had for speaking for Davy when others 8.28: the Comte, the pronounced in] the 30.25-26: no Doubt but that he] no Doubt that Comte, he pronounced in he 8.29: haunted the House of] haunted the house 30.35-36: to the Greater -

H. P. Lovecraft-A Bibliography.Pdf

X-'r Art Hi H. P. LOVECRAFT; A BIBLIOGRAPHY compiled by Joseph Payne/ Brennan Yale University Library BIBLIO PRESS 1104 Vermont Avenue, N. W. Washington 5, D. C. Revised edition, copyright 1952 Joseph Payne Brennan Original from Digitized by GOO UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA L&11 vie 2. THE SHUNNED HOUSE. Athol, Mass., 1928. bds., labels, uncut. o. p. August Derleth: "Not a published book. Six or seven copies hand bound by R. H. Barlow in 1936 and sent to friends." Some stapled in paper covers. A certain number of uncut, unbound but folded sheets available. Following is an extract from the copyright notice pasted to the unbound sheets: "Though the sheets of this story were printed and marked for copyright in 1928, the story was neither bound nor cir- culated at that time. A few copies were bound, put under copyright, and circulated by R. H. Barlow in 1936, but the first wide publication of the story was in the magazine, WEIRD TALES, in the following year. The story was orig- inally set up and printed by the late W. Paul Cook, pub- lisher of THE RECLUSE." FURTHER CRITICISM OF POETRY. Press of Geo. G. Fetter Co., Louisville, 1952. 13 p. o. p. THE CATS OF ULTHAR. Dragonfly Press, Cassia, Florida, 1935. 10 p. o. p. Christmas, 1935. Forty copies printed. LOOKING BACKWARD. C. W. Smith, Haverhill, Mass., 1935. 36 p. o. p. THE SHADOW OVER INNSMOUTH. Visionary Press, Everett, Pa., 1936. 158 p. o. p. Illustrations by Frank Utpatel. The only work of the author's which was published in book form during his lifetime. -

The Drink Tank Sixth Annual Giant Sized [email protected]: James Bacon & Chris Garcia

The Drink Tank Sixth Annual Giant Sized Annual [email protected] Editors: James Bacon & Chris Garcia A Noise from the Wind Stephen Baxter had got me through the what he’ll be doing. I first heard of Stephen Baxter from Jay night. So, this is the least Giant Giant Sized Crasdan. It was a night like any other, sitting in I remember reading Ring that next Annual of The Drink Tank, but still, I love it! a room with a mostly naked former ballerina afternoon when I should have been at class. I Dedicated to Mr. Stephen Baxter. It won’t cover who was in the middle of what was probably finished it in less than 24 hours and it was such everything, but it’s a look at Baxter’s oevre and her fifth overdose in as many months. This was a blast. I wasn’t the big fan at that moment, the effect he’s had on his readers. I want to what we were dealing with on a daily basis back though I loved the novel. I had to reread it, thank Claire Brialey, M Crasdan, Jay Crasdan, then. SaBean had been at it again, and this time, and then grabbed a copy of Anti-Ice a couple Liam Proven, James Bacon, Rick and Elsa for it was up to me and Jay to clean up the mess. of days later. Perhaps difficult times made Ring everything! I had a blast with this one! Luckily, we were practiced by this point. Bottles into an excellent escape from the moment, and of water, damp washcloths, the 9 and the first something like a month later I got into it again, 1 dialed just in case things took a turn for the and then it hit. -

The Evolution Trilogy

1 The Evolution Trilogy Todd Borho 2 Contents Part 1 – James Bong Series - 4 Part 2 – SeAgora Novel - 184 Part 3 – Agora One Novel - 264 3 James Bong Premise: Anarchism, action, and comedy blended into a spoof of the James Bond franchise. Setting: Year: 2028 Characters and Locations: James Bong – Former MI6 asset for special operations. Now an anarchist committed to freeing people from statist hands. 30 years old, well built, steely gray eyes, dirty blond hair. Bong moves frequently. K – Nerdy anarchist hacker in his early twenties based in Acapulco, Mexico. Miss Moneybit – Feisty, attractive blogger in her late twenties and based in Washington, DC. General Small - Bumbling and incompetent General. Former Army Intel and now with the CIA. Sir Hugo Trax – MI6 officer who was involved in training and controlling Bong during Bong’s MI6 days. Episode 1 – Part 1 Scene 1 Bong is driving at a scorching speed down a desert highway in a black open-source 3D printed vehicle modeled after the Acura NSX. K’s voice: Bong! Bong (narrows eyes at encrypted blockchain based smartwatch): K, what the hell? I had my watch off! K (proud, sitting in his ridiculously overstuffed highback office chair): I know, I turned it on remotely. I’ve got great news! Bong (looking ahead at the cop car and the cop’s victim on the side of the road): Kinda busy right now. K (twirling in his chair): It can’t wait! It’s a go! It’s a go! I’m so excited! Bong (sarcastically): You’re breaking up on me. -

Hidden Leaves from the Necronomicon XIX Their Hidden

Hidden Leaves From The Necronomicon XIX Their Hidden Place I have seen much unmeant for mortal eyes in my wanderings beneath that dark and forgotten city. It is not the splendours of Irem that haunt my dreams with this madness, but another place, a place shrouded in utter silence; long unknown to man and shunned even by ghoul and nightgaunt. A stillness likened to millions of vanished years pressed with great heaviness upon my soul as I trod those labyrinths in terror, ever fearing that my footfalls might awaken the dread architects of this nameless region where the hand of time is bound and the wind does not whisper. Great was my fear of this place, but greater was the strange sleep-like fascination that gripped my mind and guided my feet ever downwards through realms unknown. My lamp cast it's radiance upon basalt walls, revealing mighty pillars hewn surely by no human hand, where curiously stained obelisks engraved with frightful images and cryptic characters reared above me into the darkness. A passage sloped before me, I descended. For what seemed to be an eternity I descended rapt in contemplation of the grim icons that stretched endlessly on either hand, depicting the strange deeds of Those Great Ones born not of mortal womb. They had dwelt here and passed on, yet the walls of the edifice bore Their mark: vast likenesses of those terrible beings of yore carved beneath a firmament of unguessed asterisms. Endlessly the way led downwards, ever downwards. The passage oftime had fled from my mind, Hypnos and eternity held my soul. -

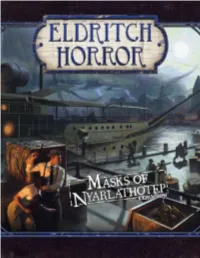

Eldritch Horror Components Except for the Components Itself, Charred Skin and Still-Hot Embers Flaking from the Limb

THE CHARRED MAN EXPANSION OVERVIEW Calvin Wright huddled in a corner of the empty barn. His tattered In the Masks of Nyarlathotep expansion, investigators must clothes were covered in dirt and bloodstains and reeked of death. It embark on an epic, world-spanning campaign to hinder the had been weeks since he had been able to change them. The ringing devious plots of multiple cults. Should they fail, Nyarlathotep, in his ears was growing louder. It is coming, Calvin thought to the Messenger of the Outer Gods, will succeed at opening the himself. Sure enough, tenebrous tendrils of inky-black smoke snaked Great Gate and bringing doom upon the Earth. This expansion their way toward him from cracks in the walls. includes two new Ancient Ones and new investigators, Calvin stared ahead, unblinking, unflinching, as the tendrils Monsters, and encounters. lashed violently past him, slicing his cheek, blood oozing from the This expansion also features new mechanics, including Personal fresh wound. He dug his fingernails into his forearm and clenched Stories, Unique Assets, Focus, and Resources. In addition, it his teeth as the dark shapes coalesced gradually into the vaguely introduces a new way to play: campaign mode. humanoid shape of a creature he had come to know all too well. Appearing to be burnt from head to toe, the creature’s skin was pitch black and gave off a faint orange glow, as if it burned from within. “What do you want, demon?” Calvin growled. USING THIS EXPANSION The entity responded with a voice that sounded to Calvin like the snapping of bones. -

Evolution Through the Search for Novelty

EVOLUTION THROUGH THE SEARCH FOR NOVELTY by JOEL LEHMAN B.S. Ohio State University, 2007 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science in the College of Engineering and Computer Science at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2012 Major Professor: Kenneth O. Stanley c 2012 Joel Lehman ii ABSTRACT I present a new approach to evolutionary search called novelty search, wherein only behav- ioral novelty is rewarded, thereby abstracting evolution as a search for novel forms. This new approach contrasts with the traditional approach of rewarding progress towards the objective through an objective function. Although they are designed to light a path to the objective, objective functions can instead deceive search into converging to dead ends called local optima. As a significant problem in evolutionary computation, deception has inspired many tech- niques designed to mitigate it. However, nearly all such methods are still ultimately sus- ceptible to deceptive local optima because they still measure progress with respect to the objective, which this dissertation will show is often a broken compass. Furthermore, al- though novelty search completely abandons the objective, it counterintuitively often out- performs methods that search directly for the objective in deceptive tasks and can induce evolutionary dynamics closer in spirit to natural evolution. The main contributions are to (1) introduce novelty search, an example of an effective search method that is not guided by actively measuring or encouraging objective progress; (2) validate novelty search by apply- ing it to biped locomotion; (3) demonstrate novelty search's benefits for evolvability (i.e. -

Regeln Für Mystische-Ruinen- Brandblasen Werfen

DER VERBRANNTE ÜBERBLICK Calvin Wright kauerte in der Ecke einer leeren Scheune. Seine zerlumpte Die Erweiterung Masken des Nyarlathotep schickt die Ermittler auf Kleidung war mit Blut und Schmutz verkrustet und stank nach Verwesung; eine epische, weltumspannende Kampagne, bei der es darum geht, er hatte sie seit Wochen nicht gewechselt. Das Pfeifen in seinen Ohren die teuflischen Pläne mehrerer Kulte zu durchkreuzen. Sollten sie wurde zusehends lauter. ‚Er ist im Anmarsch‘, dachte Calvin bei sich. Bald scheitern, wird Nyarlathotep, der Bote der Äußeren Götter, das Große schon krochen schattenhafte Tentakel aus tintenschwarzem Rauch durch die Tor öffnen und damit das Schicksal der Erde besiegeln. Mit dabei sind Risse in den Wänden und schlängelten auf ihn zu. zwei neue Große Alte sowie zahlreiche neue Ermittler, Monster und Ohne zu blinzeln, ohne auch nur mit der Wimper zu zucken, starrte Begegnungen. Calvin geradeaus, während die Fangarme an ihm vorbeischossen und seine Außerdem bietet die Erweiterung brandneue Spielmechaniken in Wange aufschlitzten. Blut quoll aus der frischen Wunde. Er krallte sich Form von persönlichen Geschichten, besonderen Unterstützungen, mit den Fingernägeln in seine Unterarme und biss die Zähne zusammen, Fokusmarkern und Ressourcen. Darüber hinaus gibt es eine völlig während die dunklen Formen allmählich zu einer menschenähnlichen neue Spielvariante: den Kampagnenmodus. Gestalt verschmolzen, die ihm nur allzu gut bekannt war. Sie schien von Kopf bis Fuß verbrannt zu sein, hatte kohlrabenschwarze Haut und verströmte ein fahles rötliches Leuchten, als würde sie von innen heraus glühen. ERWENDUNG DER RWEITERUNG „Was willst du, Dämon?“, fauchte Calvin. V E Das Wesen antwortete mit einer Stimme, die Calvin an das Knacken von Um mit der Erweiterung Masken des Nyarlathotep zu spielen, Knochen erinnerte. -

Acoustic Behavior and Ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus Mocinno, a Flagship Tropical Bird Species Pablo Rafael Bolanos Sittler

Acoustic behavior and ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno, a flagship tropical bird species Pablo Rafael Bolanos Sittler To cite this version: Pablo Rafael Bolanos Sittler. Acoustic behavior and ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno, a flagship tropical bird species. Biodiversity and Ecology. Museum national d’histoire naturelle - MNHN PARIS, 2019. English. NNT : 2019MNHN0001. tel-02048769 HAL Id: tel-02048769 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02048769 Submitted on 25 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Ecole Doctorale Sciences de la Nature et de l’Homme – ED 227 Année 2019 N°attribué par la bibliothèque |_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| THESE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DU MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Spécialité : écologie Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Pablo BOLAÑOS Le 18 janvier 2019 Acoustic behavior and ecology of the Resplendent Quetzal Pharomachrus mocinno, a flagship tropical bird species Sous la direction de : Dr. Jérôme SUEUR, Maître de Conférences, MNHN Dr. Thierry AUBIN, Directeur de Recherche, Université Paris Saclay JURY: Dr. Márquez, Rafael Senior Researcher, Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid Rapporteur Dr.