Antonio Iturbe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Cultural Life in the Theresienstadt Ghetto- Dr. Margalit Shlain [Posted on Jan 5Th, 2015] People Carry Their Culture with Them W](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3476/cultural-life-in-the-theresienstadt-ghetto-dr-margalit-shlain-posted-on-jan-5th-2015-people-carry-their-culture-with-them-w-673476.webp)

Cultural Life in the Theresienstadt Ghetto- Dr. Margalit Shlain [Posted on Jan 5Th, 2015] People Carry Their Culture with Them W

Cultural Life in the Theresienstadt Ghetto- Dr. Margalit Shlain [posted on Jan 5th, 2015] People carry their culture with them wherever they go. Therefore, when the last Jewish communities in Central Europe were deported to the Theresienstadt ghetto (Terezin in Czech), they created a cultural blossoming in the midst of destruction, at their last stop before annihilation. The paradoxical consequence of this cultural flourishing, both in the collective memory of the Holocaust era and, to a certain extent even today, is that of an image of the Theresienstadt ghetto as having had reasonable living conditions, corresponding to the image that the German propaganda machine sought to present. The Theresienstadt ghetto was established in the north-western part of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia on November 24, 1941. It was allegedly to be a "Jewish town" for the Protectorate’s Jews, but was in fact a Concentration and Transit Camp, which functioned until its liberation on May 8, 1945. At its peak (September 1942) the ghetto held 58,491 prisoners. Over a period of three and a half years, approximately 158,000 Jews, from the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Germany, Austria, Holland, Denmark, Slovakia, and Hungary, as well as evacuees from other concentration camps, were transferred to it. Of these, 88,129 were sent on to their death in the 'East', of whom only 4,134 survived. In Theresienstadt itself 35,409 died from "natural" causes like illness and hunger, and approximately 30,000 inmates were liberated in the ghetto. This ghetto had a special character, as the Germans had intended to turn it into a ghetto for elderly and privileged German Jews, according to Reinhard Heydrich’s announcement at the "Wannsee Conference" which took place on January 20th, 1942 in Berlin. -

Universidade Estadual De Campinas Instituto De Estudos Da Linguagem

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM JACQUELIN DEL CARMEN CEBALLOS GALVIS RETORNO SEM RETORNO ÀS CIDADES DA MORTE CAMPINAS 2020 JACQUELIN DEL CARMEN CEBALLOS GALVIS RETORNO SEM RETORNO ÀS CIDADES DA MORTE Tese de doutorado apresentada ao Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem da Universidade Estadual de Campinas como parte dos requisitos exigidos para obtenção do título de Doutora em Teoria e História Literária na área de Teoria e Crítica Literária. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Márcio Orlando Seligmann-Silva Este exemplar corresponde à versão final da Tese defendida por Jacquelin Del Carmen Ceballos Galvis e orientada pelo Prof. Dr. Márcio Orlando Seligmann- Silva. CAMPINAS 2020 Ficha catalográfica Universidade Estadual de Campinas Biblioteca do Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem Leandro dos Santos Nascimento - CRB 8/8343 Ceballos Galvis, Jacquelin Del carmen, 1978- C321r CebRetorno sem retorno às cidades da morte / Jacquelin Del carmen Ceballos Galvis. – Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2020. CebOrientador: Márcio Orlando Seligmann-Silva. CebTese (doutorado) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. Ceb1. Kulka, Otto Dov, 1933-. Paisagens da metrópole da morte : reflexões sobre a memória e a imaginação. 2. Testemunho. 3. Memória. 4. Luto. I. Seligmann-Silva, Márcio Orlando.. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. III. Título. Informações para Biblioteca Digital Título em outro idioma: Retorno sin retorno a las ciudades de la muerte Palavras-chave em inglês: Kulka, -

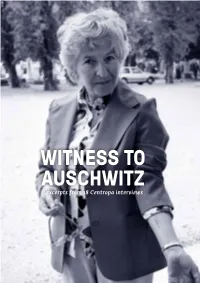

WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews WITNESS to AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews

WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ excerpts from 18 Centropa interviews WITNESS TO AUSCHWITZ Excerpts from 18 Centropa Interviews As the most notorious death camp set up by the Nazis, the name Auschwitz is synonymous with fear, horror, and genocide. The camp was established in 1940 in the suburbs of Oswiecim, in German-occupied Poland, and later named Auschwitz by the Germans. Originally intended to be a concentration camp for Poles, by 1942 Auschwitz had a second function as the largest Nazi death camp and the main center for the mass extermination of Europe’s Jews. Auschwitz was made up of over 40 camps and sub-camps, with three main sec- tions. The first main camp, Auschwitz I, was built around pre-war military bar- racks, and held between 15,000 and 20,000 prisoners at any time. Birkenau – also referred to as Auschwitz II – was the largest camp, holding over 90,000 prisoners and containing most of the infrastructure required for the mass murder of the Jewish prisoners. 90 percent of Auschwitz’s victims died at Birkenau, including the majority of the camp’s 75,000 Polish victims. Of those that were killed in Birkenau, nine out of ten of them were Jews. The SS also set up sub-camps designed to exploit the prisoners of Auschwitz for slave labor. The largest of these was Buna-Monowitz, which was established in 1942 on the premises of a synthetic rubber factory. It was later designated the headquarters and administrative center for all of Auschwitz’s sub-camps, and re-named Auschwitz III. All the camps were isolated from the outside world and surrounded by elec- trified barbed wire. -

The “Family Camp“ (B II B) of the Theresienstadt Deportees in Birkenau - Dr

The “Family Camp“ (B II b) of the Theresienstadt Deportees in Birkenau - Dr. Margalith Shlain [March 2013] On September 6, 1943, a transport with 5,007 Jewish prisoners from the Czech lands left ghetto Theresienstadt, “able-bodied” men with their families; they were chosen by the authorities to be sent purportedly to a labor camp but in fact to the concentration and extermination camp Auschwitz-Birkenau. In the framework of preparations for the visit of a delegation of the International Red Cross in the ghetto, planned for spring 1944, the Germans renewed transports from Theresienstadt as a solution for the overcrowding in the ghetto, after a pause of 7 months. It seems that the idea was to build a camp similar to Theresienstadt, to serve the Nazi propaganda and to weaken the potential for resistance in Theresienstadt (after the Jewish uprising in ghetto Warsaw). When they arrived in Auschwitz, no “selection” was carried out at the railway platform, families were not separated and none of them was sent to be killed in the gas chambers; their clothes were not changed and their hair not shorn. The men, women and children were housed at the “family camp” (B II b) that was assigned to them in Birkenau, though women and men were in separate blocks. In December 1943 a further 5,007 Jewish prisoners from Theresienstadt joined them and the camp with an area of 150 by 750 meters became quite full. In May 1944 another 7,503 Jewish prisoners from the ghetto arrived and the number of deportees from Theresienstadt in the “family camp” reached 17,517 persons . -

Dita Kraus, “The Librarian of Auschwitz”

TRIBUTE RESOLUTION HONORING DITA KRAUS, “THE LIBRARIAN OF AUSCHWITZ” Whereas January 27, 2020, was the 75th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, a World War II concentration camp in Poland created by Nazi Germany; Whereas Dita Kraus, “the librarian of Auschwitz,” was born July 12, 1929 in Prague as Edith (“Dita”) Polokova; Whereas Dita Kraus was deported to Theresienstadt in November 1942 for being of Jewish heritage, and then, at age 13, in December 1942, to Auschwitz where she received the tattoo 73305 on her lower left arm, she was assigned to Block 31, the Kinderblock (Children’s Block), where the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele kept the children that were destined to be used for his medical experiments; Whereas In this inhuman and dehumanizing environment, the young Dita maintained a library for the younger children with the guidance of teacher Fredy Hirsch; Whereas Dita Kraus’s library consisted of just eight books, including a Czech translation of The History of the World by G.H. Wells, smuggled from the luggage of Jews arriving on the selection ramps at Auschwitz; Whereas Dita Kraus kept the flame and passion of learning alive as a librarian who gave her younger charges a look at the world, a world most of them would never know; Whereas Dita Kraus used her small library as an affirmation of life, an interior intellectual oasis, and sought with only a handful of books, fragments at best, a defense against the inhumanity of the Nazi killing machine; Whereas We librarians know the saying that books have their own fate, -

DAS IST: Das Jüdische Brünn Herunterladen5 MB

TIC BRNO ↓ DAS IST: Das Jüdische Brünn 21. 1. 1890 — 15. 7. 1971 1. 6. 1893 — 27. 7. 1968 TIC BRNO ← PERSÖNLICHKEITEN01PERSÖNLICHKEITEN01 21. 1. 1890 — 15. 7. 1971 1. 6. 1893 — 27. 7. 1968 TIC BRNO ← TICTIC BRNOBRNO ↓↓ GeborenGeboren in: in: Malacky Malacky GeborenGeboren in: in: Bystřice Bystřice nad nad Pernštejnem Pernštejnem GOGO TO TO BRNO.cz BRNO.cz ←← GestorbenGestorben in: in: Liverpool Liverpool GestorbenGestorben in: in: Brünn Brünn DASDAS IST:IST: GedenktafelGedenktafel in in der der Beethovenova-Str. Beethovenova-Str. 4 4 GeländeGelände Zoo Zoo Brünn Brünn DasDas JüdischeJüdische BrünnBrünn ERNSTERNST WIESNER WIESNER (Vlněna)(Vlněna) durch. durch. Ernst Ernst Wiesner Wiesner fl fl ohoh ausaus BrünnBrünn OTTOOTTO EISLER EISLER inin das das Konzentrationslager Konzentrationslager Auschwitz, Auschwitz, wo wo amam 15. 15. März März 1939 1939 mit mit einem einem der der letzten letzten Züge, Züge, erer seinen seinen Bruder Bruder Moritz Moritz traf. traf. Sie Sie überlebten überlebten EinEin herausragender herausragender jüdischer jüdischer Architekt, Architekt, dem dem kurzkurz vor vor der der deutschen deutschen Okkupation. Okkupation. Er Er ver- ver- EinEin Mann, Mann, dessen dessen Leben Leben Gegenstand Gegenstand eines eines gemeinsamgemeinsam den den Todesmarsch Todesmarsch nach nach Buchen- Buchen- BrünnBrünn sein sein modernes modernes Gesicht Gesicht verdankt. verdankt. Ernst Ernst brachtebrachte denden KriegKrieg inin Großbritannien,Großbritannien, wowo erer AbenteuerfiAbenteuerfi lms lms seinsein könnte.könnte. DerDer -

6 Theresienstadt

21 Theresienstadt „Also, Theresienstadt, das war ein großer Betrug. Alles dort war Betrug.“ 1 2. Theresienstadt 2.1. Von Terezín zu Theresienstadt 2.1.1. Terezín Als im Oktober 1780 Kaiser Josef II. den Grundstein für eine Befestigungsanlage 60 Kilometer nördlich von Prag legte, die preußische Invasoren daran hindern sollte nach Prag vorzudringen, glaubten die Gründer noch an die Bedeutung der Festung für die Verteidigung der habsburgischen Monarchie. Die Garnisonsstadt, die der Kaiser nach seiner Mutter Maria Theresia benannt hatte, verlor jedoch bald ihre erhoffte strategische Bedeutung. 2.1.2. Voraussetzungen für die Entstehung des Konzentrationslagers Im Auftrag von Heinrich Himmler 2 wurde die alte Festungsstadt Terezín Ende November 1941 in das Konzentrationslager Theresienstadt umgewandelt. Theresienstadt wurde zum Sinnbild nationalsozialistischer Propaganda, welche die Welt - auch die Öffentlichkeit in Deutschland - über die Verbrechen der Nationalsozialisten in den Konzentrationslagern täuschen sollte. Himmler ließ Theresienstadt zu einem „Modellghetto” ausbauen. Der Besuch einer Kommission des Internationalen Roten Kreuzes war ein Teil ihrer Propaganda. Die Kommission wurde über die wirkliche Funktion von Theresienstadt getäuscht, indem ihnen Theresienstadt als „Potemkinsches Dorf“ vorgestellt wurde. In seinem Abschlußbericht schreibt der schweizerische Delegierte Maurice Rossell vom Internationalen Roten Kreuzes über seinen Besuch in Theresienstadt vom 23. Juni 1944, „(...) im Ghetto eine Stadt zu finden, die fast ein normales Leben lebt.” 1 Interview mit Frau S. in Deutschland. April 1999. S. 11, Z. 43 f. 2 Heinrich Himmler (7.10.1900-23.5.1945) war ab 1933 Polizeipräsident von München, ab 1936 Chef der deutschen Polizei, ab 1943 Reichsinnenminister und ab Juli 1944 Befehlshaber des Ersatzheeres. Er ist mitverantwortlich für den Ausbau der Konzentrationslager und für die Ermordung von Juden in Osteuropa. -

Love and Family in the Jewish Past

University of California at San Diego HITO 106 LOVE AND FAMILY IN THE JEWISH PAST Winter quarter 2015 Professor Deborah Hertz Department of History HSS 6024 858 534 5501 Office Hours: Tuesdays and Thursdays 11-12 Class meets Tuesdays and Thursdays 12:30—1:50 in HSS 1305 Rather than sending me emails, it is better to speak to me before or after class or call me in my office during my office hour. Better yet, come to office hours!!!! Course Description. This course explores Jewish women’s experiences from the seventeenth century to the present, covering Europe, the United States, and Israel. We examine work, marriage, motherhood, spirituality, education, community and politics across three centuries and three continents. Requirements. Students should do the reading and come prepared for discussion in class. This is a small class and we shall rely on each student for vigorous debate in the classroom!!! Ongoing conversations on our TED web site: please post a very short [no more than five sentences] comment on the readings on the evening before those texts are discussed in class, for at least 10 out of the class sessions. Your contributions to our TED conversations will count toward the 10 points of your grade focused on class participation. [If you have difficulty logging onto the site, please visit the Academic Computing Services office in the AP and M Building, 2113, 858 822 3315. Log in by visiting the site http://TED.ucsd.edu.] 1 Essays and class presentations. Students are expected to write a 15 page essay, due at the end of the quarter. -

Holocaust Education Week Presented By

HOLOCAUST EDUCATION WEEK PRESENTED BY An intergenerational experience at the Neuberger’s Yom Hashoah Yom at the Neuberger’s experience An intergenerational for the Neuberger. Dahlia Katz Photography Photo: 2019. commemoration, UJA Federation of Greater Toronto is the Neuberger’s sustaining sponsor. UJA is proud to support the Neuberger’s world- class programming during Holocaust Education Week and its year-round educational and remembrance programs. facebook.com/HoloCentre @Holocaust_Ed @Holocaust_Ed Annual Student Symposium. Photo: Seed9 for Photo: Annual Student Symposium. the Neuberger. Cover photos: Pola Garfinkle (Paula Dash), Allison Nazarian’s grandmother, sewing in the Lodz Ghetto, circa 1941-2. Courtesy of Allison Nazarian via the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. / Rally participant, 2018. Photo: Lorie Shaull. / Caring Corrupted archival images courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Holocaust Museum, Houston, and US Library of Congress via the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. We are delighted to welcome you to the 39th year of Holocaust Education Week. As you flip through this year’s guide, you will see that our programs curated around the theme, The Holocaust and Now, appear to have been “torn from the headlines.” With so much social, cultural and political turmoil occurring globally, we find ourselves discussing the relationship between the Holocaust and what is happening around us today. It is both timely and necessary for HEW to address our current zeitgeist–the rise of global antisemitism, denial, hate crimes, both online and in our own neighbourhoods, a reckoning with difficult aspects of our Canadian past; and conversely, an examination of how the legacy of the Holocaust has inspired positivity, action and change. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES The Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile and the Jews during World War 2 (1938-1948) By Jan Láníček Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 1 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Doctor of Philosophy THE CZECHOSLOVAK GOVERNMENT-IN-EXILE AND THE JEWS DURING WORLD WAR 2 (1938-1948) by Jan Láníček The thesis analyses Czechoslovak-Jewish relations in the twentieth century using the case study of the Czechoslovak Government-in-Exile in London and its activities during the Second World War. In order to present the research in a wider perspective, it covers the period between the Munich Agreement, when the first politicians left Czechoslovakia, and the Communist Coup in February 1948. Hence the thesis evaluates the political activities and plans of the Czechoslovak exiles, as well as the implementation of the plans in liberated Czechoslovakia after 1945. -

Gemeinsam Auf Dem Weg Zur Erinnerung

Tandem Koordinierungszentrum Deutsch-Tschechischer Jugendaustausch Koordinační centrum česko-německých výměn mládeže Gemeinsam auf dem Weg zur Erinnerung Materialien und Methodenbausteine für deutsch-tschechische Erinnerungsarbeit Impressum Herausgeber Koordinierungszentrum Deutsch-Tschechischer Jugendaustausch – Tandem Maximilianstraße 7 · 93047 Regensburg Koordinační centrum česko-německých výměn mládeže Tandem Westböhmische Universität in Pilsen Riegrova 17 · 306 14 Plzeň Redaktion Bernhard Schoßig, Thomas Rudner, Jan Lontschar, Jitka Walterová Übersetzungen Milada Vlachová Copyright Tandem und die Autorinnen und Autoren Gestaltung und Satz Marko Junghänel, München Titelbild Tandem/Filip Singer Druck Schmidl Druck GmbH, Lappersdorf Auflage 1. Auflage 2015, 1.000 Exemplare ISBN 978-3-925628-00-9 Die Koordinierungszentren fördern die gegenseitige Annäherung und die Entwicklung freundschaftlicher Beziehungen zwischen jungen Menschen aus Deutschland und Tschechien. Die Koordinierungszentren beraten und unterstützen staatliche und nichtstaatliche Institutionen und Organisationen in Deutschland und Tschechien bei der Durchführung und Intensivierung des deutsch-tschechischen Jugendaustausches und der internationalen Zusammenarbeit im Bereich der Jugendarbeit. Im Zentrum der Arbeit steht die Begegnung junger Menschen. Gemeinsam auf dem Weg Gefördert durch das Bundesministerium für Familie, zur Erinnerung Senioren, Frauen und Jugend und durch das Ministerium für Schule, Jugend und Sport der Tschechischen Republik Materialien und Methodenbausteine -

Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Teachers' Program Summer 2014

Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Teachers’ Program Summer 2014 Documents Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Teachers’ Program American Gathering of Holocaust Survivors and Their Descendants 122 W 30th St # 205 New York, NY 10001-4009 (212) 239-4230 www.hajrtp.org June – July 2014 Program Directors Elaine Culbertson Stephen Feinberg COPYRIGHT NOTICE The Content here is provided under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License (“CCPL” or “license”). This Content is protected by copyright and/or other applicable law. Any use of the Content other than as authorized under this license or copyright law is prohibited. By exercising any rights to the work provided here, you accept and agree to be bound by the terms of this license. To the extent this license may be considered to be a contract, the licensor grants you the rights contained here in consideration of your acceptance of such terms and conditions. Under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License, you are invited to copy, distribute and/or modify the Content, and to use the Content here for personal, educational, and other noncommercial purpose on the following terms: • You must cite the author and source of the Content as you would material from any printed work. • You must also cite and link to, when possible, the website as the source of the Content. • You may not remove any copyright, trademark, or other proprietary notices, including attribution, information, credits, and notices that are placed in or near the Content. • You must comply with all terms or restrictions other than copyright (such as trademark, publicity, and privacy rights, or contractual restrictions) as may be specified in the metadata or as may otherwise apply to the Content.