Short-Acting Inhaled B2-Agonists: Why, Whom, What, How?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Validation of New Analytical Methodology for Determining Fenoterolhydrobromide by HPLC: Application in Pharmaceutical Products

Artigo Original/Original Article Validation of new analytical methodology for determining fenoterolhydrobromide by HPLC: application in pharmaceutical products Validação de uma nova metodologia analítica para determinação de bromidrato de fenoterol por CLAE: aplicações em produtos farmacêuticos RIALA6/1475 *Helena Miyoco YANO1, Fernanda Fernandes FARIAS1, Marcelo Beiriz DEL BIANCO1, Pedro Lopez GARCIA2 *Endereço para correspondência: 1Núcleo de Ensaios Físicos e Químicos em Medicamentos, Centro de Medicamentos, Cosméticos e Saneantes, Instituto Adolfo Lutz, Av. Doutor Arnaldo, 355, CEP: 01246-902, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] 2Departamento de Farmácia, Faculdade de Ciências Farmacêuticas, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. Recebido: 31.10.2011- Aceito para publicação: 20.04.2012 RESUMO Bromidrato de fenoterol é um agente agonista adrenérgico β2-seletivo utilizado para tratamento de asma e doenças pulmonares crônicas obstrutivas. A metodologia analítica por cromatografia líquida de alta eficiência (CLAE) foi desenvolvida e validada para a determinação quantitativa de bromidrato de fenoterol. A condição analítica empregada incluiu coluna em fase reversa C18 (150 mm × 3,9 mm d.i., 5 µm) Thermo®, fase móvel composta de mistura de acetonitrila e água (30:70, v/v) com 0,1% de trietilamina e pH ajustado para 5,0 com ácido fórmico, vazão de 1,0 mL.min-1 e detecção em UV a 276 nm. A faixa de linearidade foi de 0,025 a 0,15 mg.mL-1; a curva analítica mostrou coeficiente de correlação > 0,999. O limite de detecção (LD) foi de 0,003 mg.mL-1 e o limite de quantificação de 0,012 mg.mL-1. -

Ep 2560611 B1

(19) TZZ Z___T (11) EP 2 560 611 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61K 9/00 (2006.01) 03.01.2018 Bulletin 2018/01 (86) International application number: (21) Application number: 11719211.2 PCT/EP2011/056227 (22) Date of filing: 19.04.2011 (87) International publication number: WO 2011/131663 (27.10.2011 Gazette 2011/43) (54) "PROCESS FOR PROVIDING PARTICLES WITH REDUCED ELECTROSTATIC CHARGES" VERFAHREN ZUR BEREITSTELLUNG VON PARTIKELN MIT REDUZIERTEN ELEKTROSTATISCHEN LADUNGEN PROCÉDÉ DE PRÉPARATION DE PARTICULES AYANT DES CHARGES ÉLECTROSTATIQUES RÉDUITES (84) Designated Contracting States: • GUCHARDI ET AL: "Influence of fine lactose and AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB magnesium stearate on low dose dry powder GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO inhaler formulations", INTERNATIONAL PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICS, ELSEVIER BV, NL LNKD- DOI:10.1016/J.IJPHARM.2007.06.041, (30) Priority: 21.04.2010 EP 10160565 vol. 348, no. 1-2, 19 December 2007 (2007-12-19), pages 10-17, XP022393884, ISSN: 0378-5173 (43) Date of publication of application: • ELAJNAF A ET AL: "Electrostatic 27.02.2013 Bulletin 2013/09 characterisation of inhaled powders: Effect of contact surface and relative humidity", (73) Proprietor: Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A. EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHARMACEUTICAL 43100 Parma (IT) SCIENCES, ELSEVIER, AMSTERDAM, NL LNKD- DOI:10.1016/J.EJPS.2006.07.006, vol. 29, no. 5, 1 (72) Inventors: December 2006 (2006-12-01), pages 375-384, • COCCONI, Daniela XP025137181, ISSN: 0928-0987 [retrieved on I-43100 Parma (IT) 2006-12-01] • MUSA, Rossella • CHAN ET AL: "Dry powder aerosol drug I-43100 Parma (IT) delivery-Opportunities for colloid and surface scientists", COLLOIDS AND SURFACES. -

ADD/ADHD: Strattera • Allergy/Anti-Inflammatories

EXAMPLES OF PERMITTED MEDICATIONS - 2015 ADD/ADHD: Strattera Allergy/Anti-Inflammatories: Corticosteroids, including Decadron, Depo-Medrol, Entocort, Solu-Medrol, Prednisone, Prednisolone, and Methylprednisolone Anesthetics: Alcaine, Articadent, Bupivacaine HCI, Chloroprocaine, Citanest Plain Dental, Itch-X, Lidocaine, Marcaine, Mepivacaine HCI, Naropin, Nesacaine, Novacain, Ophthetic, Oraqix, Paracaine, Polocaine, Pontocaine Hydrochloride, PrameGel, Prax, Proparacaine HCI, Ropivacaine, Sarna Ultra, Sensorcaine, Synera, Tetracaine, Tronothane HCI, and Xylocaine Antacids: Calci-Chew, Di-Gel, Gaviscon, Gelusil, Maalox, Mintox Plus, Mylanta, Oyst-Cal 500, Rolaids, and Tums Anti-Anxiety: Alprazolam, Atarax, Ativan, Buspar, Buspirone HCI, Chlordiazepoxide HCI, Clonazepam, Chlorazepate Dipotassium, Diastat, Diazepam, Hydroxyzine, Klonopin, Librium, Lorazepam, Niravam, Tranxene T-tab, Valium, Vistaril, and Xanax Antibiotics: Acetasol HC, Amoxil, Ampicillin, Antiben, Antibiotic-Cort, Antihist, Antituss, Avelox, Ceftazidime, Ceftin, Cefuroxime Axetil, Ceptaz, Cleocin, Cloxapen, Cortane-B Aqueous, Cortic, Cresylate, Debrox, Doryx, EarSol-HC, Fortaz, Gantrisin, Mezlin, Moxifloxacin, Neotic, Otocain, Principen, Tazicef, Tazidime, Trioxin, and Zyvox Anti-Depressants: Adapin, Anafranil, Asendin, Bolvidon, Celexa, Cymbalata, Deprilept, Effexor, Elavil, Lexapro, Luvox, Norpramin, Pamelor, Paxil, Pristiq, Prozac, Savella, Surmontil, Tofranil, Vivactil, Wellbutrin, Zoloft, and Zyban Anti-Diabetics: Actos, Amaryl, Avandia, Glipizide, Glucophage, -

Ep 2626065 A1

(19) TZZ Z_T (11) EP 2 626 065 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION published in accordance with Art. 153(4) EPC (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: A61K 31/137 (2006.01) A61K 31/135 (2006.01) 14.08.2013 Bulletin 2013/33 A61K 31/4704 (2006.01) A61K 31/58 (2006.01) A61K 31/56 (2006.01) A61K 9/12 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 11827927.2 A61K 9/14 A61P 11/06 (86) International application number: Date of filing: 01.02.2011 (22) PCT/CN2011/070883 (87) International publication number: WO 2012/041031 (05.04.2012 Gazette 2012/14) (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventor: WU, Wei-hsiu AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB Taipei GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO Taiwan (TW) PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR (74) Representative: Patentanwaltskanzlei WILHELM (30) Priority: 28.09.2010 CN 201010502339 & BECK Prinzenstrasse 13 (71) Applicant: Intech Biopharm Ltd. 80639 München (DE) Taipei (TW) (54) COMPOUND COMPOSITION FOR INHALATION USED FOR TREATING ASTHMA (57) An inhaled pharmaceutical composition con- tric way as a controller. The eccentric way control therapy tains primary active ingredients of beta2- agonist and cor- could create a low blood concentration period during the ticosteroids.The pharmaceuticalcompositions disclosed day and minimize the acute tolerance phenomenon (or in the present invention are to be inhaled by a patient so called tachyphylaxis) for bronchodilator - beta2-ago- when needed as a reliever, or administrated in an eccen- nists in treating asthma or other obstructive respiratory disorders. -

5 August 2004 Version

The study listed may include approved and non-approved uses, formulations or treatment regimens. The results reported in any single study may not reflect the overall results obtained on studies of a product. Before prescribing any product mentioned in this Register, healthcare professionals should consult prescribing information for the product approved in their country. Study No.: SAM 30020 Title: Efficacy and tolerability of the salmeterol/fluticasone 50/100 mcg combination Diskus, inhaled once daily in the evening, in comparison to the p.r.n. inhalation from the reproterol/sodium cromoglycate 0.5/ 1 mg combination MDI, as initial therapy for patients with mild asthma – a multicentre, randomised, open, parallel trial Rationale: The reproterol/sodium cromoglycate 0.5/ 1 mg combination is still widely used for the treatment of mild asthmatics. Usually, patients inhale the combination product from an MDI, and they adjust the dosage according to their asthma symptoms. Anti-inflammatory medication with an inhaled corticosteroid such as fluticasone is an alternative therapeutic option, and long-acting beta agonists can be used as bronchodilatory treatment. The study aimed to investigate whether the efficacy of the salmeterol/fluticasone 50/100-mcg combination (SFC), inhaled from the Diskus once daily in the evening, is superior to that of the PRN inhalation of the reproterol/sodium cromoglycate 0.5/ 1 mg combination (RS) from the metered dose inhaler. Phase: IV Study Period: 13 June 2002 to 27 June 2003 Study Design: This randomised, prospective, open, parallel group study had a total duration of ten weeks. There were two study periods: a run-in period of two weeks, and a treatment period of 8 weeks. -

That Had Torte I Una Altra Manian Literatura

THAT HAD TORTE I USUNA 20180016601A1ALTRA MANIAN LITERATURA UNA ( 19) United States (12 ) Patent Application Publication ( 10) Pub . No. : US 2018 / 0016601 A1 Qi et al. ( 43 ) Pub . Date: Jan . 18 , 2018 ( 54 ) METHODS FOR MODULATING GENOME C12N 15 / 10 (2006 .01 ) EDITING A6IK 38 / 46 ( 2006 .01 ) A61K 31 /365 (2006 .01 ) ( 71) Applicants: The Board of Trustees of the Leland A61K 31/ 63 ( 2006 .01 ) Stanford Junior University , Palo Alto , A61K 31 /513 ( 2006 . 01 ) CA (US ) ; The J . David Gladstone A61K 31 /505 ( 2006 .01 ) Institutes , a Testamentary Trust C12Q 1 / 68 ( 2006 .01 ) established under the Will of J . David C12N 9 / 22 ( 2006 . 01 ) Glads, San Francisco , CA ( US) ; The (52 ) U . S . CI. Regents of the University of CPC . .. - . C12N 15/ 907 ( 2013 .01 ) ; C12Q 1 /68 California , Oakland , CA (US ) ( 2013 . 01 ) ; C12Q 1 /44 ( 2013 .01 ) ; C12N 15 / 1024 (2013 .01 ) ; C12N 9 /22 ( 2013. 01 ) ; ( 72 ) Inventors : Lei S . Qi, Palo Alto , CA (US ) ; Sheng A61K 31/ 365 ( 2013 . 01) ; A61K 31 /63 Ding , Orinda , CA ( US ) ; Chen Yu , San ( 2013 .01 ) ; A61K 31/ 513 ( 2013 . 01 ) ; A61K Francisco , CA (US ) 31/ 505 ( 2013. 01 ) ; A61K 38 /465 (2013 . 01 ) (57 ) ABSTRACT ( 21 ) Appl. No. : 15 / 649, 304 Provided herein are methods and kits for modulating (22 ) Filed : Jul. 13 , 2017 genome editing of target DNA . The invention includes using small molecules that enhance or repress homology - directed Related U . S . Application Data repair (HDR ) and / or nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ ) (63 ) Continuation of application No . PCT /US2016 / repair of double - strand breaks in a target DNA sequence . -

The Use of Stems in the Selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for Pharmaceutical Substances

WHO/PSM/QSM/2006.3 The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances 2006 Programme on International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Quality Assurance and Safety: Medicines Medicines Policy and Standards The use of stems in the selection of International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for pharmaceutical substances FORMER DOCUMENT NUMBER: WHO/PHARM S/NOM 15 © World Health Organization 2006 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization can be obtained from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press, at the above address (fax: +41 22 791 4806; e-mail: [email protected]). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. -

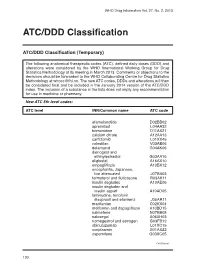

ATC/DDD Classification

WHO Drug Information Vol. 27, No. 2, 2013 ATC/DDD Classification ATC/DDD Classification (Temporary) The following anatomical therapeutic codes (ATC), defined daily doses (DDD) and alterations were considered by the WHO International Working Group for Drug Statistics Methodology at its meeting in March 2013. Comments or objections to the decisions should be forwarded to the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology at [email protected]. The new ATC codes, DDDs and alterations will then be considered final and be included in the January 2014 version of the ATC/DDD index. The inclusion of a substance in the lists does not imply any recommendation for use in medicine or pharmacy. New ATC 5th level codes: ATC level INN/Common name ATC code afamelanotide D02BB02 apremilast L04AA32 brimonidine D11AX21 calcium citrate A12AA13 carfilzomib L01XX45 colestilan V03AE06 delamanid G04AK06 dienogest and ethinylestradiol G03AA16 eliglustat A16AX10 empagliflozin A10BX12 encephalitis, Japanese, live attenuated J07BA03 formoterol and fluticasone R03AK11 insulin degludec A10AE06 insulin degludec and insulin aspart A10AD05 lamivudine, tenofovir disoproxil and efavirenz J05AR11 macitentan C02KX04 metformin and dapagliflozin A10BD15 nalmefene N07BB05 naloxegol A06AH03 nomegestrol and estrogen G03FB12 obinutuzumab L01XC15 ocriplasmin S01AX22 ospemifene G03XC05 Continued/ 130 WHO Drug Information Vol. 27, No. 2, 2013 ATC/DDD Classification ATC level INN/Common name ATC code pomalidomide L04AX06 serelaxin C01DX21 strontium ranelate and colecalciferol -

100 Storage Condition=50 C/Ambrh

USOO595.5058A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: S.9SS,0589 9 Jager et al. (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 21,9 1999 54). STABILIZED MEDICINAL AEROSOL 56) References Cited SOLUTION FORMULATIONS CONTAINING U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS IPRATROPIUM BROMIDE a 5,118,494 6/1992 Schultz et al. ............................ 424/45 75 Inventors: Paul Donald Jager, Waterbury; Mark 5,190,029 3/1993 Byron et al. ... ... 128/200.14 James Kontny, New Milford, both of 5,225,183 7/1993 Purewal et al. ........................... 424/45 Conn.; Jurgen Hubert Nagel 5.439,670 8/1995 Purewal et al. ... 424/45 Ingelheim/Rhein, Germany s 5,605,674 2/1997 Purewal et al. ........................... 424/45 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 73 Assignee: Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Ridgefield, 0372 777 6/1990 European Pat. Off.. Conn. Primary Examiner Raj Bawa Attorney, Agent, or Firm Morgan & Finnegan, LLP 21 Appl.pp No.: 08/843,180 57 ABSTRACT 22 Filed: Apr. 14, 1997 Stabilized medicinal aeroSol Solution formulations compris O O ing medicaments that degrade or decompose by interaction Related U.S. Application Data with solvents or water, an HFC propellant, a cosolvent and an acid are described. Further, Specific medicinal aeroSol 63 Staggypt.NE "A iGs Solution formulations comprising ipratropium bromide or No. 08/153.549, Nov. 22, 1993, abandoned E. is a fenoterol, ethyl alcohol, 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane or 1,1,1, continuation-in-part of application No. 07/987,852, Dec. 9, 2,3,3,3-heptafluoropropane, and either an inorganic acid or 1992, abandoned. an organic acid are described. The acids are present in 51 Int. -

WO 2014/141069 Al 18 September 2014 (18.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/141069 Al 18 September 2014 (18.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, 150 Industrial A61K 9/00 (2006.01) A61K 31/00 (2006.01) Road, San Carlos, California 94070 (US). A61K 9/16 (2006.01) (74) Agent: MAZZA, Michael; Novartis Vaccines and Dia (21) International Application Number: gnostics, Inc., 4560 Horton Street, Emeryville, California PCT/IB2014/059632 94608 (US). (22) International Filing Date: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 11 March 2014 ( 11.03.2014) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (25) Filing Language: English BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, (26) Publication Language: English DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (30) Priority Data: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, 61/784,865 14 March 2013 (14.03.2013) US MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US) : NO¬ OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, VARTIS AG [CH/CH]; Lichtstrasse 35, CH-4056 Basel SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, (CH). -

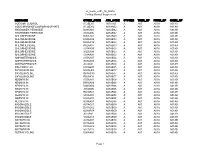

Vr Meds Ex01 3B 0825S Coding Manual Supplement Page 1

vr_meds_ex01_3b_0825s Coding Manual Supplement MEDNAME OTHER_CODE ATC_CODE SYSTEM THER_GP PHRM_GP CHEM_GP SODIUM FLUORIDE A12CD01 A01AA01 A A01 A01A A01AA SODIUM MONOFLUOROPHOSPHATE A12CD02 A01AA02 A A01 A01A A01AA HYDROGEN PEROXIDE D08AX01 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB HYDROGEN PEROXIDE S02AA06 A01AB02 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE B05CA02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D08AC02 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE D09AA12 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE R02AA05 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S01AX09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S02AA09 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB CHLORHEXIDINE S03AA04 A01AB03 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B A07AA07 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B G01AA03 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB AMPHOTERICIN B J02AA01 A01AB04 A A01 A01A A01AB POLYNOXYLIN D01AE05 A01AB05 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE D08AH03 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE G01AC30 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB OXYQUINOLINE R02AA14 A01AB07 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN A07AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN B05CA09 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN D06AX04 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN J01GB05 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN R02AB01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S01AA03 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S02AA07 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB NEOMYCIN S03AA01 A01AB08 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE A07AC01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE D01AC02 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE G01AF04 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE J02AB01 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB MICONAZOLE S02AA13 A01AB09 A A01 A01A A01AB NATAMYCIN A07AA03 A01AB10 A A01 -

Pharmacology and Therapeutics of Bronchodilators

1521-0081/12/6403-450–504$25.00 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Vol. 64, No. 3 Copyright © 2012 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 4580/3762238 Pharmacol Rev 64:450–504, 2012 ASSOCIATE EDITOR: DAVID R. SIBLEY Pharmacology and Therapeutics of Bronchodilators Mario Cazzola, Clive P. Page, Luigino Calzetta, and M. Gabriella Matera Department of Internal Medicine, Unit of Respiratory Clinical Pharmacology, University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata,’ Rome, Italy (M.C., L.C.); Department of Pulmonary Rehabilitation, San Raffaele Pisana Hospital, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico, Rome, Italy (M.C., L.C.); Sackler Institute of Pulmonary Pharmacology, Institute of Pharmaceutical Science, King’s College London, London, UK (C.P.P., L.C.); and Department of Experimental Medicine, Unit of Pharmacology, Second University of Naples, Naples, Italy (M.G.M.) Abstract............................................................................... 451 I. Introduction: the physiological rationale for using bronchodilators .......................... 452 II. -Adrenergic receptor agonists .......................................................... 455 A. A history of the development of -adrenergic receptor agonists: from nonselective  Downloaded from adrenergic receptor agonists to 2-adrenergic receptor-selective drugs.................... 455  B. Short-acting 2-adrenergic receptor agonists........................................... 457 1. Albuterol........................................................................ 457