Essays: Archaeologists and Missionaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Cincinnati

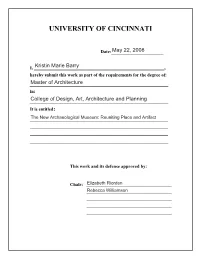

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________May 22, 2008 I, _________________________________________________________,Kristin Marie Barry hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Architecture in: College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning It is entitled: The New Archaeological Museum: Reuniting Place and Artifact This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________Elizabeth Riorden _______________________________Rebecca Williamson _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The New Archaeological Museum: Reuniting Place and Artifact Kristin Barry Bachelor of Science in Architecture University of Cincinnati May 30, 2008 Submittal for Master of Architecture Degree College of Design, Art, Architecture and Planning Prof. Elizabeth Riorden Abstract Although various resources have been provided at archaeological ruins for site interpretation, a recent change in education trends has led to a wider audience attending many international archaeological sites. An innovation in museum typology is needed to help tourists interpret the artifacts that been found at the site in a contextual manner. Through a study of literature by experts such as Victoria Newhouse, Stephen Wells, and other authors, and by analyzing successful interpretive center projects, I have developed a document outlining the reasons for on-site interpretive centers and their functions and used this material in a case study at the site of ancient Troy. My study produced a research document regarding museology and design strategy for the physical building, and will be applicable to any new construction on a sensitive site. I hope to establish a precedent that sites can use when adapting to this new type of visitors. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank a number of people for their support while I have been completing this program. -

Turkeyâ•Žs Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities

International Journal of Legal Information the Official Journal of the International Association of Law Libraries Volume 38 Article 12 Issue 2 Summer 2010 7-1-2010 Who Owns the Past? Turkey’s Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities Kathleen Price Levin College of Law, University of Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli The International Journal of Legal Information is produced by The nI ternational Association of Law Libraries. Recommended Citation Price, Kathleen (2010) "Who Owns the Past? Turkey’s Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities," International Journal of Legal Information: Vol. 38: Iss. 2, Article 12. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/ijli/vol38/iss2/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Legal Information by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Who Owns the Past? Turkey’s Role in the Loss and Repatriation of Antiquities KATHLEEN PRICE* “Every flower is beautiful in its own garden. Every antiquity is beautiful in its own country.” --Sign in Ephesus Museum lobby, quoted in Lonely Planet Turkey (11th ed.) at 60. “History is beautiful where it belongs.”—OzgenAcar[Acar Erghan] , imprinted on posters in Turkish libraries, classrooms, public buildings and shops and quoted in S. Waxman, Loot at 151; see also S. Waxman ,Chasing the Lydian Hoard, Smithsonian.com, November 14, 2008. The movement of cultural property1 from the vanquished to the victorious is as old as history. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

Scholars Debate Homer's Troy

Click here for Full Issue of Fidelio Volume 11, Number 3-4, Summer-Fall 2002 Appendix: Scholars Debate Homer’s Troy Hypothesis and the Science of History he main auditorium of the University of Tübingen, eries at the site of Troy (near today’s Hisarlik, Turkey) for TGermany was packed to the rafters for two days on more than a decade. In 2001 they coordinated an exhibi- February 15-16 of this year, with dozens fighting for tion, “Troy: Dream and Reality,” which has been wildly standing room. Newspaper and journal articles had popular, drawing hundreds of thousands to museums in drawn the attention of all scholarly Europe to a highly several German cities for six months. They gradually unusual, extended debate. Although Germany was hold- unearthed a grander, richer, and militarily tougher ing national elections, the opposed speakers were not ancient city than had been found there before, one that politicians; they were leading archeologists. The magnet comports with Homer’s Troy of the many gates and broad of controversy, which attracted more than 900 listeners, streets; moreover, not a small Greek town, but a great was the ancient city of Troy, and Homer, the deathless maritime city allied with the Hittite Empire. Where the bard who sang of the Trojan War, and thus sparked the famous Heinrich Schliemann, in the Nineteenth century, birth of Classical Greece out of the dark age which had showed that Homer truly pinpointed the location of Troy, followed that war. and of some of the long-vanished cities whose ships had One would never have expected such a turnout to hear sailed to attack it, Korfmann’s team has added evidence a scholarly debate over an issue of scientific principle. -

Fall of Troy VII: New Archaeological Interpretations and Considerations

evidence regarding the question of a Trojan War is by no means conclusi ve (Sperling 1984:29). Fall of Troy VII: New Archaeological After a summary of the Homeric version of the Trojan War, I will give a brief explanation Interpretations and Considerations concerning the Homeric topography of the Trojan plain; in other words, I will explain why archaeologists have come to accept modem day Hisarlik as the site of ancient Troy. Swept into their city like a herd of Subsequently, having established the necessary frightened deer. the Trojans dried the sweat off their bodies. and drank and background information, the plimary section of quenched their thirst as they leant this paper wil1 be devoted to presenting the against the massive battlements. evidence believed to be indicative of an actual while the Achaeans advanced on the Trojan War. To this end, using post-processual wall with their shields at the slope. But Fate for her own evil purposes methodology, I hope to clitical1y evaluate such kept Hector where he was. olltside the evidence as being either suppOitive, contrary, or town in front of the Scaean Gate at present, inconclusive as to the validity of a (Homer. Iliad 22.1-6). historical Trojan War. It should also be noted, that if I am to This passage is from Homer's Iliad, an carry out such an attempt under the precepts of epic poem believed to have been composed post-processual archaeology, the issue of bias during the middle of the eighth century B.C. should be addressed. As "post-processual that accounts the last few weeks of the Greeks' archaeologists have pointed out, there are no ten-year siege on the city of Troy. -

Development of High Resolution Caesium Magnetometry 1992-1994

Fig. [. Troy 1894. Excavation of the fortification wall of the citadel of Troy VI by Wilhelm Dorpfcld in 1894 H. Becker In Search for the City Wall of Homers Troy - Development of High Resolution Caesium Magnetometry 1992-1994 Collaboration of Bavarian State Conservation Office, Depart• More than 100 years later the modern excavations in the ruins ment Archaeological Prospection and Aerial Archaeology of Hisarlik-Troy undertaken since 1988 by M. Korfmann (Uni• (H. Becker, J. W. E. Fassbinder) and the Troy Project. Universi• versity of Tubingen for the pre-Roman periodcs) and C. Rose ty of Tubingen and University of Cincinatti (M. Korfmann, (University of Cincinatti for the Hellenistic and Roman periods) B. Rose, H. G. Jansen) unearthed also some settlement patterns outside of the fortifica• Since 1868 when Heinrich Schliemann came to Troy trying to tion wall of the 6"' "city" Troy VI of the citadel which gave evi• verify the story of the Trojan war the site remains a focus for ar• dence for a "lower settlement" but there was still the city wall chaeological research. Schliemann worked very hard searching missing which should surround the "lower city" of Late Bronze the lower city of Troy as described in the Iliad. After the excava• AgeTroy VI. tion of numerous "wells" (today we would say deep trenches) Troy became a test field for the development of high resolu• and finding only pottery of the Roman and Greek period, but tion caesium magnetometry and marks the enormous step from none of older types which would be expected for the remains of Nanotesla- to Picotesla systems 1992/1993 and 1994. -

J03: Greek Lightstructures

1 Ancient Lighthouses - Part 3: Early Greek Aids To Navigation by Ken Trethewey Gravesend Cottage, Torpoint, Cornwall, PL11 2LX, UK Abstract: This paper offers an analysis of the methods of navigation used by the earliest Greek naviga- tors and their contributions to the building of lighthouses. Introduction his paper will consider groups of people who BCE Tpopulated the central Mediterranean over 0 thousands of years and who proved to be expert Hellenic Pharos of 323 to 31 Alexandria mariners. The landscapes in which they made their 280 homes were rugged and littered with thousands Classical of reefs, rocks and islands from the very small and 500 to 323 barely habitable to the large, resource-rich isles Archaic 750 to like Cyprus, Rhodes, Crete and Sicily where whole 500 new societies could seed and grow to maturity. Travel by sea between these widely separated col- Dark Ages 1100 to 1000 onies was of the utmost necessity, and where sea 750 Late travel was so perilous, the finest skills of technolo- Bronze Age gy and expertise were honed. Diverse at first, these Civilisation Mycaenean small centres of wisdom and progressive ideas 1600 to grew into a unified whole that we now identify 1100 as Greek, and that had a profound impact on the western civilization that many of us enjoy today. Minoan Helladic 2700 to 2800 to 1450 1600 Objectives 2000 The objectives of this paper are: 1. To describe the practices of sea travel in the different periods of ancient Greece. Cycladic 2. To identify the methods by which Greek 3200 to mariners navigated the seas. -

William James Stillman

WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project William James Stillman HDT WHAT? INDEX WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN 1828 William James Stillman was born in a family of 7th-Day Baptists in Schenectady, New York. HDT WHAT? INDEX WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN 1848 William James Stillman graduated from the Union College of Schenectady. He would study art under Frederic Edwin Church. HDT WHAT? INDEX WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN 1850 Influenced by MODERN PAINTERS, William James Stillman sailed for England, where he would seek out John Ruskin. He would have an opportunity also to meet J.M.W. Turner, and would fall under the influence of Rossetti and Millais. After his return to America he would come to be described as “the American Pre- Raphaelite.” HDT WHAT? INDEX WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN WILLIAM JAMES STILLMAN 1852 In London, Lajos Kossuth became an intimate of Giuseppe Mazzini, and joined his revolutionary committee. ITALY Thomas Mayne Reid, Jr.’s THE YOUNG VOYAGEURS; OR, THE BOY HUNTERS IN THE NORTH. The author engaged in a plan for Kossuth to travel incognito across Europe as his man-servant “James Hawkins” under a Foreign Office passport “for the free passage of Captain Mayne Reid, British subject, travelling on the Continent with a man-servant.” In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s THE BLITHEDALE ROMANCE there was talk of the reading of THE DIAL: Being much alone, during my recovery, I read interminably [page 677] in Mr. Emerson’s Essays, the Dial, Carlyle’s works, George Sand’s romances, (lent me by Zenobia,) and other books which one or another of the brethren or sisterhood had brought with them. -

Religioso.Pdf

RELIGIOUS ORIGIN AND LEGENDS OF CASTILLA ACUDECTO - SEGOVIA ORIGIN AND LEGENDS OF CASTILLA BURGOS PALENCIA BURGOS ATAPUERCA PALENCIA COBARRUBIAS SANTO DOMINGO DE SILOS SORIA LERMA VALLADOLID BURGO DE OSMA VALLADOLID AYLLÓN SEGOVIA From $ SEGOVIA 409 3 Days I 2 Nights MADRID MADRID Areas: Castilla y León MONASTERIO SILOS Tour Type: Urban, Religious, Historical Day 01 . Madrid- Ayllon- Burgos De Osma- Monasterio De Silos- Covarrubias- Burgos.- Welcome to your Europamundo Trip Style!!! The information about the meeting place and start time of your circuit can be found on your voucher. We leave to the Northern Mountains of Madrid, and at the beautiful town of AYLLÓN, in the vicinity of the Mountains with the same name, with its red archi- tecture and medieval atmosphere. We continue towards BURGO DE OSMA, an ancient and monumental episco- pal city, located in the province of Soria and known for its history and beautiful Cathedral (entrance included). We visit the SAINT DOMINGO OF SILOS MONASTERY (admission includ- CATEDRAL BURGOS ed), a place of spiritual refuge and one the most beautiful places to admire the Spanish Romanic Art, unique in Europe. Then we arrive at the noble city of CO- VARRUBIAS, with its old walled case, its typical Houses. In the Collegiate Church we can admire the triptych and also visit the tomb of Fernán Gonzalez, first count of Castilla. and its interesting vintage weapons collection. After a brief journey, arrival and accommodation in the city of BURGOS. Day 02 . Burgos- Atapuerca- Lerma- Palencia.- After breakfast time to get to know the city of BURGOS, crossroads; its spectacular Gothic Cathedral stands out, built for more than three centuries, where the tomb of El Cid and his wife Da. -

Download and Read Here

THOMAS FARRER AND THE PRE-RAPHAELITE MOVEMENT IN AMERICA by Lawrence B. Siddall The Pre-Raphaelite movement in American art was brief, lasting only ten years from about 1857 to1867. It appeared quickly on the horizon and then virtually vanished. In that short time, however, the movement made a significant impact. Yet little is known about it today. “It is a largely forgotten chapter in American Art”.1 What most defined this movement was the desire to revolutionize art in America and establish an aesthetic that was based on the principle of truth in nature as found in the writings of John Ruskin, the mid-19th century British critic, writer and artist. Ruskin wrote: “The word truth, as applied to art, signifies the faithful statement, either to the mind or senses, of any fact of nature.”2 While some of the artists associated with this movement called themselves Realists or Naturalists, most preferred the term Pre-Raphaelite because they saw their cause as similar to that of the Pre-Raphaelite artists in England who also wanted to change the course of art, in their case rejecting the traditional and rigid standards of the Royal Academy. The British artists, too, had been strongly influenced by the writings of Ruskin and took the name Pre-Raphaelite because they believed that true art existed only in Italian painting prior to Raphael. One difference between the British and American movements was the fact that the British artists had a preference for figural painting, whereas the Americans focused more on landscape, still-life and what was called the nature study (as distinct from a sketch). -

Troy and Homer

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Troy and Homer Version 1.0 November 2005 Ian Morris Stanford University Abstract: This is a review of Joachim Latacz’s book Troy and Homer: Towards a Solution of an Old Mystery (2004), focusing on the archaeological issues. © Ian Morris. [email protected] 1 Troy and Homer: Towards a Solution of an Old Mystery. By JOACHIM LATACZ. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2004. Pp. xix + 342. Cloth, $45.00. This is an excellent book by one of Europe’s leading Homerists. In the 1840s, well before Schliemann set spade to soil at Hisarlik, George Grote suggested that while Homer’s epics were excellent sources for the customs of eighth-century-BC Greece, we would never know whether the Trojan War he described really took place.1 Schliemann and Dörpfeld shocked classicists out of this view, but since the 1980s positions like Grote’s have returned to favor.2 The Trojan War itself dropped out of historians’ analyses of Homer, because it seemed that there was really very little we could say. Joachim Latacz argues to the contrary that the late Manfred Korfmann’s excavations at Troy since 1988 have changed the equation. Korfmann was the first archaeologist to explore Troy’s lower town. Against those who insisted that Troy VI (c. 1700-1200 BC) was basically just a castle on a hill, inconsistent with Homer’s account of windy Ilion, Korfmann concluded that the city covered some 20 hectares, with a population of 7,000-10,000 people. Its lower town was fortified, and its rulers grew rich by controlling trade between the Aegean and Black Seas. -

Neo-Pre-Raphaelitism: the Final Generations

Neo-Pre-Raphaelitism: The Final Generations Amanda B. Waterman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Susan Casteras, Chair Stuart Lingo Joseph Butwin Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art History ©Copyright 2016 Amanda B. Waterman University of Washington Abstract Neo Pre-Raphaelitism: The Final Generations Amanda B. Waterman Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Susan P. Casteras Art History The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group of seven young men who wanted to rebel against the teachings and orthodoxies of the Royal Academy. It was a short-lived movement, beginning in 1848 and ending in the early 1850s, but this dissertation will argue that their influence lived on and inspired a group of artists who were working at the turn of the century and well into the twentieth-century. This dissertation is unprecedented; it is the first publication which aims to specifically categorize certain artists whose oeuvres are indebted to various generations of Pre-Raphaelitism. In short, I am characterizing these artists and thereby dubbing them “Neo-Pre-Raphaelite,” channeling an early twentieth-century description of some of these artists. The most obvious reason to refer to them by this term is that they are stylistically and/or thematically linked to members of the original PRB or later generations / manifestations of Pre-Raphaelitism. The individuals on whom I am focusing are all British and produced Pre-Raphaelite inspired work from roughly 1895-1950. Consequently, the parameters within which I am working are threefold; firstly, the artists were exhibiting in the late 1880s/1890 – 1920 (a Neo-Pre-Raphaelite period that overlapped for most of them); secondly, those whose work echoed that of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood; and thirdly, persons having a working relationship with Edwin Austin Abbey—an American artist who was in a unique position to be a hybrid between the earlier PRB and these younger artists.