Praise for the Dawn Prayer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Student Numbers Drop

Recliner, $425 SPORTS In Today’s PAGE 1 Classifieds! AND WEEKLY Charlotte Sun HERALD RAYS WIN AGAIN ON ROAD FLORIDA CITRUS IN CRISIS Evan Longoria singles home the winning run in the 10th inning The $9 billion industry is facing its biggest threat yet, thanks to a as Tampa Bay takes its eighth victory in past 11 away games. mottled brown bug no bigger than a pencil eraser. THE WIRE PAGE 1 An Edition of the Sun VOL. 122 NO. 237 AMERICA’S BEST COMMUNITY DAILY MONDAY AUGUST 25, 2014 www.sunnewspapers.net $1.00 HACKIN’ AROUND Jerry Wilson Student numbers drop By ADAM KREGER enrollment has slipped for funding for education to entire operation.” is all STAFF WRITER the third straight year, and over $19.6 billion, which At the start of the current is down almost 11 percent equates to districts receiv- school year — which began Florida Gov. Rick Scott from nine years ago. ing $7,176 per student — a for most schools last week announced Thursday that “It’s a concern from the $232 per-student increase — there were 15,968 stu- shook up per-student spending perspective that it means over the current school year, dents enrolled in Charlotte should be the highest in the declining revenue,” said according to a press release County’s public schools. erry Wilson loves Elvis Presley. state’s history next year. Doug Whittaker, superin- from Scott’s office. When the 2003-04 Anyone who knows the local car However, the news comes tendent of Charlotte County “That money gets spread school year began, there J dealer knows that. -

LEAVING Hotill CALAFORNIX

LEAVING HOtILL CALAFORNIX Undamming the world’s rivers, forcing the collection of that which falls from the heavens and/or your ass, o camillo. An autobiographic historical expose, for Life. Introit I’m John Lawrence Kanazawa Jolley. Currently life on the planet is having a stroke, diagnosed from a human’s anatomy point of view, severe blockage of its flow ways. From life’s point of view humans are dam, slacker home building, ditch digging, drain the well dry, devil’s GMO food of the god’s, monocultural, sewage pumpers or porous dam sheddy flushtoile.t. ecocide artists. Compounding this problem is a machine/computer/vessel/organism that creates clone doppelganger pirates that’ve highjacked the surface guilty of the same crime. If we do anything well its intuitive container transportation. This is the case. I’m educated University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Environmental Horticulture. I’m a trapper, gardener, carpenter, fisherperson, cooper and teacher. Drainage is the most important idea to consider when gardening. I paddled a canoe across North America and back, been through Lake Sacagawea twice. I’m a bullfighter, the foremost gardener in the world, the point spokesman for life, the man himself, hole puncher, obstacle remover, the pencil man, the one, Christ almighty. The character who appears again when it’s an “Obama nation of desolation” to save the world from damnation. I’m a specialist, designed specifically to solve the currentless dam problem. The timeliest, most intelligent, aggressive, offensive, desperate character ever created, for a reason. The health of life on the planet is in severe question. -

Nothing Is Impossible

Nothing is Impossible. Autobiography of William Hamilton Robertson (Known as Wullie, Scottie, Ginger, Sparks and Bill) Ballenbreich by Avonbridge, Falkirk Me my mum and Fred Explanation about Fred KARNO who I refer to in this book. Frederick John Westcott (26 March 1866 – 18 September 1941), best known by his stage name Fred Karno, was a theatre impresario of the British music hall. Karno is credited with inventing the custard-pie-in –the-face gag. During the 1890s, in order to circumvent stage censorship, Karno developed a form of sketch comedy without dialogue. Cheeky authority defying playlets such as “Jail Birds” (1896) in which prisoners play tricks on warders and “Early Birds” (1903) where a small man defeats a large ruffian in London’s East End can be seen as precursors of movie silent comedy. In fact, among the young comedians who worked for him were Charlie Chaplin and Arthur Jefferson, who later adopted the name of Stan Laurel. These were part of what was known as “Fred Karno’s Army”, a phrase still occasionally used in the U.K. to refer to a chaotic group or organisation. The phrase was also adopted by British solders into a trench song in the First World War, as a parody of, or rather to the tune of, the hymn “The Church’s One Foundation”. In the Second World War it was adapted as the anthem of “The Guinea Pig Club”, the first line becoming ”We are McIndoe’s Army”. The men, having their burnt faces etc. rebuilt, by the Famous Plastic Surgeon Mr. -

At Thirty-Three, My Anger Hasn't Subsided. It's Gotten

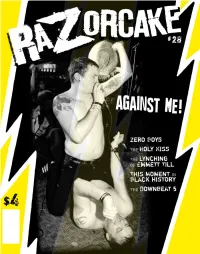

t thirty-three, my anger hasn’t subsided. It’s gotten And to all this, I don’t have a real answer. I don’t think I’m naïve. I deeper. It’s more like magma keeping me warm instead of lava don’t think I’m expecting too much, but it’s hard not to feel shat upon by AAshooting haphazardly all over the place. It’s managed. You see, the world-at-large every step of the way. There are a couple of things that I’ve been able to channel the balled-fist, I’m hitting-walls-and-breaking- temper my anger. First off, when we were doing our math, I got another knuckles anger into something of a long-burning fuse. Oh, I’m angry, but number: sixty-four. That’s how many folks help out Razorcake in some I’m probably one of the calmest angry people you’re likely to meet. I take way, shape, or form on a regular basis. Damn, that’s awesome. Sixty- all of my “fuck yous” and edit. I take my “you’ve got to be fucking kid- four people, without whom this zine would just be a hair-brained ding me”s and take pictures and write. I seek revenge by working my ass scheme. off. Anger, coupled with belief, is a powerful motivator. The second element is a little harder to explain. Recently, I was in an What do I have to be angry about? I don’t think it’s obvious, but we do adjacent town, South Pasadena. -

Model Builder September 1972

CARL GOLDBERG MODELS THAT '«RANGER 42 The Versatile Almost- ARE REALLY Ready-To-Fly Fun Model. $1995 GREAT TO FLY! SKYLANE 62 © Takes Single To 4 Channel Proportional Radio. Molded Fuselage...One Piece Molded Wing, Stabilizer and Vertical Fin. Also Free Flight. Span 42". Weight 26 oz. For .049— Semi-Scale Beauty in .10 Engines. a Great Flying Model! I $2295 1-Piece Full-Length Sides ToU8h Roomy Cabin and Front End. For 2 To 4 Channel Proportional Steerable Nose Gear. Span 62". Weight 4>/2-5 Lbs. For 35 To .45 Engines. *OJ FEATURES: Now With 1-Piece Full-Length Sides. Takes 2 to 4 Channel Pro portional. Span 56". Weight 3V4-4V4 lbs. For .15-.19-.35 Engines. • See-through cabin, with die-cut plywood cabin sides FEATURES: • Shaped leading edges plus sheeting • Semi-symmetrical wing section • Coil-sprung nose gear. • Cleanly die-cut parts that fit formed main gear i / R Q w w & r • Shaped and notched leading and • Clark Y wing section, hardwood struts For Single or 2 Channel, trailing edges Pulse or Digital. Span 37" • Steerable nose gear, formed main gear • Cleanly die-cut ribs, fuse sides, Weight 18 oz. For .049 formers, etc. Engines. • New simple "Symmet-TRU'' $8.95 1/2A SKYLANE $9.95 wing construction For Single or 2 Channel, Pulse or Digital Span 4 2". Weight 22 0 2 . For .049 To -10 Engines Š A o e íto ittq $ 2 9 9 5 The GnndvearGoodyear Rar.prRacer With FnmiPhEnough ^ Area and Stability So You Can Fly It! For 4 Channel Proportional. -

Risk Criticism: Precautionary Reading in an Age of Environmental

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages RISK CRITICISM Revised Pages Revised Pages Risk Criticism PRECAUTIONARY READING IN AN AGE OF ENVIRONMENTAL UNCERTAINTY Molly Wallace UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © 2016 by Molly Wallace All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2019 2018 2017 2016 4 3 2 1 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Wallace, Molly, author. Title: Risk criticism : precautionary reading in an age of environmental uncertainty / Molly Wallace. Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2015038637 | ISBN 9780472073023 (hardback) | ISBN 9780472053025 (paperback) | ISBN 9780472121694 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Ecocriticism. | Criticism. | Risk in literature. | Environmental risk assessment. | Risk-taking (Psychology) Classification: LCC PN98.E36 W35 2016 | DDC 809/.93355— dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015038637 Revised Pages For my family Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This book has been a number of years in the writing, and I am deeply grate- ful for the support and encouragement that I have received along the way. -

Advance Praise for the Writing Workshop

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR THE WRITING WORKSHOP “There are many guides to scientific writing out there, and I read most of them in preparation for teaching a writing workshop at MIT. Barbara’s was the one I referred students to most often. It’s down-to-earth, funny, and packed with advice that extends well beyond the fundamentals of good scientific writing to topics rang- ing from reproducibility and open science to time management and work/life balance. The resources for instructors are also excellent: She has templates to help students set both short- and long-term goals and in-class exercises to help novice writers hear the differ- ence between clunky writing and writing that sings. What is per- haps most distinctive about Barbara’s book is that she conveys the sense that writing should be a kind of meditation practice: a way to stay grounded in a supportive community while engaging deeply with ideas from a place of focus and clarity. I can’t think of a better book to support new and emerging writers.” —LAURA SHULZ, professor of cognitive science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology “This book is a gem. Funny, thoughtful, and humane; packed with wise advice and deep insights. This is essential reading for any academic who wants to be more prolific and write better. (Which means that it’s essential reading for all of us.)” —PAUL BLOOM, Brooks and Suzanne Regan Professor of Psychology at Yale University and author of Against Empathy. “This book is practical, funny, easy to use, and effective. Reading this book is like sitting down with a close friend who also happens to be a writing expert. -

Jabhat Al-Nusra in Syria

December 2014 Jennifer Cafarella MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 25 JABHAT AL-NUSRA IN SYRIA AN ISLAMIC EMIRATE FOR AL-QAEDA Cover: Members of al Qaeda’s Nusra Front drive in a convoy as they tour villages, which they said they have seized control of from Syrian rebel factions, in the southern countryside of Idlib, December 2, 2014. REUTERS/Khalil Ashawi. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2014 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2014 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 25 JABHAT AL-NUSRA IN SYRIA AN ISLAMIC EMIRATE FOR AL-QAEDA ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jennifer Cafarella is a Syria Analyst and Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War. In her research, she focuses on the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), the al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra (JN), and Syrian rebel groups. She is the author of “ISIS Works to Merge its Northern Front across Iraq and Syria,” “Local Dynamics Shift in Response to U.S.-Led Airstrikes in Syria,” and “Peace-talks between the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria.” In addition, she oversees the research for and production of weekly Syria Update maps and periodic Syria Control of Terrain maps. -

The Song of the Lark Cather, Willa

The Song of the Lark Cather, Willa Published: 1915 Categorie(s): Fiction, Westerns Source: http://gutenberg.org 1 About Cather: Wilella Sibert Cather (December 7, 1873 – April 24, 1947) is an eminent author from the United States. She is perhaps best known for her depictions of U.S. life in novels such as O Pion- eers!, My Ántonia, and Death Comes for the Archbishop. Also available on Feedbooks for Cather: • Death Comes for the Archbishop (1927) • O Pioneers! (1913) • A Lost Lady (1923) • My Ántonia (1918) • One of Ours (1923) • Sapphira and the Slave Girl (1940) • The Professor's House (1925) • The Troll Garden and Selected Stories (1905) • Youth and the Bright Medusa (1920) • Not Under Forty (1936) Copyright: This work is available for countries where copy- right is Life+50 or in the USA (published before 1923). Note: This book is brought to you by Feedbooks http://www.feedbooks.com Strictly for personal use, do not use this file for commercial purposes. 2 Part 1 Friends of Childhood 3 Chapter 1 Dr. Howard Archie had just come up from a game of pool with the Jewish clothier and two traveling men who happened to be staying overnight in Moonstone. His offices were in the Duke Block, over the drug store. Larry, the doctor's man, had lit the overhead light in the waiting-room and the double student's lamp on the desk in the study. The isinglass sides of the hard- coal burner were aglow, and the air in the study was so hot that as he came in the doctor opened the door into his little operating-room, where there was no stove. -

Jabhat Al-Nusra in Syria

December 2014 Jennifer Cafarella MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 25 JABHAT AL-NUSRA IN SYRIA AN ISLAMIC EMIRATE FOR AL-QAEDA Cover: Members of al Qaeda’s Nusra Front drive in a convoy as they tour villages, which they said they have seized control of from Syrian rebel factions, in the southern countryside of Idlib, December 2, 2014. REUTERS/Khalil Ashawi. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2014 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2014 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 | Washington, DC 20036 www.understandingwar.org Jennifer Cafarella MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 25 JABHAT AL-NUSRA IN SYRIA AN ISLAMIC EMIRATE FOR AL-QAEDA ABOUT THE AUTHOR Jennifer Cafarella is a Syria Analyst and Evans Hanson Fellow at the Institute for the Study of War. In her research, she focuses on the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), the al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra (JN), and Syrian rebel groups. She is the author of “ISIS Works to Merge its Northern Front across Iraq and Syria,” “Local Dynamics Shift in Response to U.S.-Led Airstrikes in Syria,” and “Peace-talks between the Islamic State and Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria.” In addition, she oversees the research for and production of weekly Syria Update maps and periodic Syria Control of Terrain maps. -

The Foreign Fighters Phenomenon and Related Security Trends in the Middle East

de l’atelier de Points saillants Points The Foreign Fighters au Moyen-Orient au Phenomenon tendances connexes connexes tendances and Related sécurité et les les et sécurité Security Trends étrangers, la la étrangers, in the Middle East des combattants combattants des Le phénomène phénomène Le Highlights from the workshop Photo credit: istockphoto.com credit: Photo Canada of Right in Queen the Majesty Her © Printed in Canada in Printed Published January 2016 January Published www.csis-scrs.gc.ca are made and the identity of speakers and participants is not disclosed. not is participants and speakers of identity the and made are workshop was conducted under the Chatham House rule; therefore, no attributions attributions no therefore, rule; House Chatham the under conducted was workshop nor does it represent any formal position of the organisations involved. The The involved. organisations the of position formal any represent it does nor support ongoing discussion, the report does not constitute an analytical document, document, analytical an constitute not does report the discussion, ongoing support (CSIS) as part of the CSIS academic outreach program. Offered as a means to to means a as Offered program. outreach academic CSIS the of part as (CSIS) by speakers at, a workshop organised by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Service Intelligence Security Canadian the by organised workshop a at, speakers by This report is based on the views expressed during, and short papers contributed contributed papers short and during, expressed -

Profiles of Islamic State Leaders” By: Kyle Orton ISBN 978-1-909035-25-6!

Profles of Islamic State Leaders Kyle Orton Published in 2016 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society Millbank Tower 21-24 Millbank London SW1P 4QP Registered charity no. 1140489 Tel: +44 (0)20 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society 2016 The Henry Jackson Society All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its Trustees Title: “Governing the Caliphate: Profiles of Islamic State Leaders” By: Kyle Orton ISBN 978-1-909035-25-6! £10.00 where sold All rights reserved Photo Credits Cover Photo: Islamic State Flag http://batya-1431.deviantart.com/art/Islamic-state-flag-488615075 Governing the Caliphate: Profiles of Islamic State Leaders ! ! ! Kyle Orton www.henryjacksonsociety.org Table of Contents Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Background……………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 1.! The Caliph………………………………………………………………………………………… 16 2.! The Shura Council……………………………………………………………………………… 24 3.! The Military Council…………………………………………………………………………… 37 4.! The Security and Intelligence Council…………………………………………………… 52 5.! The Shari’a Council……………………………………………………………………………. 54 6.! The Media Council…………………………………………………………………………….. 58 7.! The Cabinet………………………………………………………………………………………. 62 ! ! GOVERNING THE CALIPHATE: PROFILES OF ISLAMIC STATE LEADERS ! Introduction This paper is a comprehensive compilation of the leadership of the Islamic State (IS), the personnel and the structures by which they relate to one another within the territory governed by IS, and in its external wing that launches terrorist attacks around the world. Two years on from its declaration of a caliphate in June 2014, IS has lost 45% of its territory in Iraq and between 16% and 20% of its territory in Syria.1 But the foreign attacks continue to increase in scale and frequency.