" Der Proceβ in Yiddish, Or the Importance of Being Humorous"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3. Grzegorz Gazda

Grzegorz Gazda The Final Journey of Franz Kafka's Sisters Through me into the city full of woe; Through me the message of eternal pain; Through me the passage where the lost souls go. Dante Alighieri, Divine Comedy 1 Magic Prague, esoteric Prague, Golden Prague. 2 The capital of the Czech Republic bears those names and nicknames not without reason. It is a truly extraordinary and fascinating city. A cultural palimpsest of texts written through the ages, texts that have been magnificently preserved until our times. "An old in folio of stone pages," as V. Nezval wrote. 3 A Slavic city with over a thousand years of history, but a city which at the same time, due to historical conditions, belongs rather to the culture of the West. The capital of the Czechs in which, however, an important part has always been played by foreign ethnic communities. But this arti- cle is no place to present historical panoramas and details. Our subject matter goes back to the turn of the 20 t h century, so let us stop at that. 1 Fragment of an inscription at the gates of hell which begins the third canto of the Divine Comedy (trans. C. Carson). This quote was used as a motto in the novel Kruta leta (1963, The Cruel Years ) by Frantisek Kafka, a Czech writer and literary scholar. 1 will speak more of him and his novel in this article. 2 Among numerous books dealing with the cultural and artistic history of this city, see, for example, K. Krejci, Praga. Legenda i rzeczywistość, Warszawa 1974, trans, from the Czech by C. -

Dora Diamant – Kafkas Letzte Liebe in Neuss Ein Beitrag Zur Geschichte Des Rheinischen Landestheaters

Miszellen Annekatrin Schaller Dora Diamant – Kafkas letzte Liebe in Neuss Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte des Rheinischen Landestheaters »Das Drama (auf der Bühne) ist erschöpfender als der Roman, weil wir alles sehn, wovon wir sonst nur lesen. « Franz Kafka, Tagebücher Die Geschichte des Rheinischen Landestheaters Neuss ist noch nicht geschrieben. Sie hält zahlreiche spannende Geschichten bereit – über die reine Theatergeschichte und die Neusser Stadtgeschichte hinaus. Sie bietet zweifellos reichlich Stoff für das historische Gesche- hen seit der Weimarer Republik, einen kleinen Mosaikstein dazu möchte dieser Aufsatz beitragen. Eine Saison lang, vom Herbst 1928 bis zum Sommer 1929, gehörte eine Schauspielerin zum Ensemble des damaligen Rheinischen Städte bundtheaters, die zur literarischen Weltgeschichte zählt: Dora Diamant 1. Sie war eine ungewöhnliche Frau und eine starke Persön- Dora Diamant, um 1928 (Lask Collection) 263 Miszellen Schaller | Dora Diamant – Kafkas letzte Liebe in Neuss lichkeit mit einem bemerkenswerten Lebenslauf, und sie war »Kafkas letzte Liebe« 2 – die Frau, die dem Schriftsteller in seinem letzten Lebensjahr bis zum frühen Tod am 3. Juni 1924 zur Seite stand. An das Theater nach Neuss kam sie vier Jahre danach, im Anschluss an ihre zweijährige Ausbildung zur Schauspielerin an der Hochschule für Bühnenkunst in Düsseldorf. Das Rheinische Städtebundtheater war eine noch sehr junge Bühne, als Dora Diamant dort spielte. Erst wenige Jahre zuvor, 1925, war es gegründet worden. In seine vierte Spielzeit 1928/29 ging es mit -

Franz Kafka Und Seıne Beziehungen Zu Den Frauen (Mit Hilfe Der

A ta tü r k Ü niversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi Journal of Social Sciences CiltVolume 10, SayıNumber 45, AralıkDecember 2010, 1-19 Franz Kafka und Seıne Beziehungen Zu Den Frauen (Mit Hilfe der Frauenbildrecherche von Franz Kafka und Max Brod gemeinsam geschriebenen fragmenteren Roman “Richard und Samuel”) Franz Kafka and his Relation With Woman (Using the image of woman research of Franz Kafka and Max Brod fragments co- written novel, “Richard and Samuel”) Ahmet SARI Cemile Akyıldız ERCAN Atatürk Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Atatürk Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Alman Dili ve Edebiyatı Bölümü Alman Dili ve Edebiyatı Bölümü [email protected] [email protected] ZUSAMMENFASSUNG In diesem Aufsatz wird Kafkas Beziehungen zu den Frauen untersucht. War Kafka wirklich ein Frauenhasser, oder war er ein Casanova? Warum konnte er, obwohl er wollte, keine Beziehungen zu den Frauen knüpfen? Wollte er es nicht, weil er schreibgierig war, oder wollte er es wirklich, aber konnte er es nicht? Die Geliebten von Franz Kafka werden in diesem Aufsatz zuerst vorgestellt. Dann soll in dem mit Max Brod gemeinsam geschriebenen Reise-Roman “Richard und Samuel” das Frauenbild gezeigt und analysiert werden. Der fragmentere Roman wird uns zeigen, wie die Beziehungen der beiden Freunde Franz Kafka und Max Brod zu den Frauen sind. Anahtar Kelimeler: Franz Kafka, Max Brod, Richard und Samuel, Reiseroman, Frauen ABSTRACT In this essay, we study Kafka's relationships with women. Was Kafka really a woman-hater, or was he a Casanova? Why couldn’t he, though he did want to build relationships with women? If he did not want to have relationship with women, was that because of his love of writing, or did he really not want to do so? The lovers of Franz Kafka are mentioned in this essay first and then the image of woman found in the travel novel written collaboratively with Max Brod,” Richard and Samuel“, is demonstrated and examined. -

Kathi Diamant to the Horton Plaza Theatres Foundation Board of Directors

RECEIVED MAY 2 0 2013 OFFICE OF COUNICILMEMBER TODD GLORIA City Of San Diego COUNCILMEMBER MARTI EMERALD DISTRICT NINE MEMORANDUM DATE: May 20, 2013 Reference: M-13-05-10 TO: Council President Todd Gloria FROM: Councilmember Marti Emerald SUBJECT: Nomination of Kathi Diamant to the Horton Plaza Theatres Foundation Board of Directors It is with great pleasure that I nominate Ms. Kathi Diamant to the Horton Plaza Theatres Foundation Board of Directors. Ms. Diannant brings an impressive background in both arts and academia clearly showing her many and ongoing contributions to San Diego's cultural community. An actress herself, she performed in countless stage productions, including at the Tenth Avenue Playhouse in downtown San Diego. Ms. Diamant's more than 25 years of experience in broadcast media and print journalism include her most recent role as an on-air anchor and producer at KPBS, where she continues to volunteer in fundraising and community outreach. Ms. Diamant is a respected author, receiving countless accolades for her award-winning biography Kafka's Last Love: The Mystery of Dora Diamant. This passion-driven project led her to found and direct San Diego State University's Kafka Project, which is dedicated to investigating the lost works of internationally renowned writer Franz Kafka. She is a frequent contributor to the San Diego Union-Tribune and other Southern California publications with her articles spanning travel, arts, and culture, and shares her love of the arts with students as an adjunct professor at both San Diego State University's (SDSU) College of Arts and Letters and Osher Institute for Lifelong Learning. -

Kafka's Last Trial

Kafka’s Last Trial - NYTimes.com 9/26/10 5:04 PM Reprints This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. You can order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers here or use the "Reprints" tool that appears next to any article. Visit www.nytreprints.com for samples and additional information. Order a reprint of this article now. September 22, 2010 Kafka’s Last Trial By ELIF BATUMAN During his lifetime, Franz Kafka burned an estimated 90 percent of his work. After his death at age 41, in 1924, a letter was discovered in his desk in Prague, addressed to his friend Max Brod. “Dearest Max,” it began. “My last request: Everything I leave behind me . in the way of diaries, manuscripts, letters (my own and others’), sketches and so on, to be burned unread.” Less than two months later, Brod, disregarding Kafka’s request, signed an agreement to prepare a posthumous edition of Kafka’s unpublished novels. “The Trial” came out in 1925, followed by “The Castle” (1926) and “Amerika” (1927). In 1939, carrying a suitcase stuffed with Kafka’s papers, Brod set out for Palestine on the last train to leave Prague, five minutes before the Nazis closed the Czech border. Thanks largely to Brod’s efforts, Kafka’s slim, enigmatic corpus was gradually recognized as one of the great monuments of 20th-century literature. The contents of Brod’s suitcase, meanwhile, became subject to more than 50 years of legal wrangling. While about two-thirds of the Kafka estate eventually found its way to Oxford’s Bodleian Library, the remainder — believed to comprise drawings, travel diaries, letters and drafts — stayed in Brod’s possession until his death in Israel in 1968, when it passed to his secretary and presumed lover, Esther Hoffe. -

REVIEWS Highlights the Love Affair Between the Author and the from PAST TOURS Little-Known Dora Diamant

KAFKA PROJECT “A summer tour of Germany, Poland and the Czech Republic REVIEWS highlights the love affair between the author and the FROM PAST TOURS little-known Dora Diamant. The story unfolds in the streets Magical Mystery 2008 TOUR of Prague, Czech Republic, where the German author was Literary History Tour born, moves to the Jewish Quarter of Krakow, Poland and "The Magical Mystery Literary History Tour in 2008 was indeed incredible. The leaders were superb and extremely knowledgeable making the trip so ends in Berlin, where the couple lived the Bohemian life memorable." SEPTEMBER 5 - 14, 2014 in the early 1920s. Proceeds from the trip support the Helene W. Feldman, Ph.D., Beverly Hills, CA nonprofit Kafka Project, which seeks to recover lost letters, “This was my first trip to Europe in my life, and it was indeed magical. I journals and notebooks by the author.” didn’t really know anything about Kafka before, but now he has come alive -Mary Forgione, Travel Editor, Los Angeles Times, Dec 5, 2011 for me, and I am also one of “Kafka’s last loves!” Vernetta Bergeron, San Diego, CA “Imagine going to some of Europe's most fascinating locales, and instead of doing the generic tourist thing, visiting the most fascinating, out-of-the- YES! SIGN ME UP FOR THE TOUR... way places with a small group of similar-minded, freewheeling intellectu- als. Not only did we take the unbeaten path, we learned so much and thoroughly enjoyed the company of our fellow travelers.” Register online www.kafkaproject.com Leslie W. -

Found: a Clue to Kafka’S Missing Treasure

K A F K A P R O J E C T A T S D S U FOUND: A CLUE TO KAFKA’S MISSING TREASURE For more than 60 years, Kafka scholars have believed it possible that Kafka’s last writings (unpublished notebooks and letters written in the last year of his life) may have survived, lost among Nazi-confiscated materials which were removed from Berlin during the Allied bombing for safekeeping in Silesia. The Kafka Project at SDSU has made an exciting breakthrough in the ongoing search for this missing literary treasure, the last love letters, and writings of literary giant Franz Kafka. Since 1998, the Kafka Project at SDSU has organized the research into the 20 notebooks and 35 letters Kafka wrote in the last year of his life, which were confiscated by the Gestapo in Berlin in 1933. Nazi files on German communists in the Bundesarchiv in Berlin in September of 2014. The Kafka Project examined stacks of files like these, similar to those compiled against Dora Diamant and the Lask family, by the Gestapo in the 1930s. In 1998, the Kafka Project spent four months in Berlin’s Nazi archives, followed by a six-week research project in Poland in 2008. A 2012 residency at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington D.C. led the Kafka Project team to look to Russia, where all confiscated German materials were sent by the Red Army following WWII. In 2013, the Kafka Project discovery of a still-uncatalogued Third-Reich-era archive, which had been returned from Russia to Stasi control in East Germany during the Cold War, prompted a top Kafka German scholar to get involved and two German universities have pledged support. -

Franz Kafka in Context

FRANZ KAFKA IN CONTEXT edited by CAROLIN DUTTLINGER University of Oxford 2679CC 423:86 846 1:6:C6:C.6:6.1/,04C2CD364CCC96,23:86,6 C67D622:2362C9CC 423:86 846C6 9CC: 8 University Printing House, Cambridge cb2 8bs,UnitedKingdom One Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor, New York, ny 10006,USA 477 Williamstown Road, Port Melbourne, vic 3207,Australia 314-321, 3rd Floor, Plot 3, Splendor Forum, Jasola District Centre, New Delhi - 110025,India 79 Anson Road, #06-04/06,Singapore079906 Cambridge University Press is part of the University of Cambridge. It furthers the University’s mission by disseminating knowledge in the pursuit of education, learning, and research at the highest international levels of excellence. www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781107085497 doi: 10.1017/9781316084243 C ⃝ Cambridge University Press 2018 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2018 Printed in the United Kingdom by Clays, St Ives plc AcataloguerecordforthispublicationisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data Names: Duttlinger, Carolin, 1976–editor. Title: Franz Kafka in context / edited by Carolin Duttlinger. Description: New York : Cambridge University Press, 2017.|Series:Literatureincontext| Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifers: LCCN 2017034613 | isbn 9781107085497 -

Kafka in Love

KAFKA IN LOVE Genre: Romantic Dramedy Period: 1912 to 1924 Locations: Prague, Prague's countryside, Berlin, Vienna Pitch Between 1912 and his death in 1924, Franz Kafka was engaged four times but never married. We follow here the main relationships of his romantic life, all of which were initially long distance, through the love letters Franz exchanges with his fiancees Felice, Julie, Milena and Dora. Here, between Prague, Berlin and Vienna, the literary genius becomes a man - flawed, scared, funny and always ironically and cruelly aware of his own limitations. Beyond the tragedy of his life and the depth of his writings, Kafka is a modern lover, seducing women, often too scared to get close to them, comedic in spite of himself and always ready to make fun of himself. One of the most influential authors of the last century becomes the uniquely charming lead of an unexpected romantic dramedy. Synopsis Felice In 1912, Franz Kafka is walking in Prague at night towards his best friend's house for dinner. Max Brod and Franz Kafka met ten years before when they were both law students. Their common passion for literature brought them closer, and Max will remain Franz's best friend until his death. As he goes there every night, Franz feels at home in the joyful chaos of Max Brod's family house. That night, he meets Felice Bauer for the first time and according to what he wrote in his diary, Kafka is far from impressed by what he sees in the young woman. Nevertheless, Kafka sends Felice who lives in Berlin more than a hundred love letters in the three months that follow. -

Der Proceβ in Yiddish, Or the Importance of Being Humorous Iris Bruce

Document generated on 09/26/2021 4:55 a.m. TTR Traduction, terminologie, re?daction Der Proceβ in Yiddish, or The Importance of being Humorous Iris Bruce Traduire les sociolectes Article abstract Volume 7, Number 2, 2e semestre 1994 Der Proceß in Yiddish, or the Importance of being Humorous — The article argues for a "humorous" Franz Kafka rather than a kajkaesque one and URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/037180ar criticizes the "Kafka myth" which cristallized after WWII and emphasized DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/037180ar foremost Kafka's existential anguish. Even before the war Max Brod as well as Walter Benjamin recognized the humorous dimension in Kafka's texts, much of See table of contents which lies in word plays and gesture; otherwise, the humour in Kafka was largely ignored, especially after WWII. The focus in this article is on English, German and Yiddish cultural contexts and ideologies which have determined different readings/ translations of Kafka's texts. In particular, the article Publisher(s) compares the pre-war English translation of Der Proceß by Edwin and Willa Association canadienne de traductologie Muir, which contributes to the "Kafka myth," with a post-war Yiddish translation by Melech Ravitch, which highlights the novel's humorous qualities. Not only does the Yiddish translation place Kafka's novel within a ISSN culturally specific literary genre and suggest an alternate "Jewish" reading of 0835-8443 (print) the text; by drawing on both the English translation and the German original, 1708-2188 (digital) Ravitch also "corrects" the anguish laden "Kafka myth" and constitutes a challenge to the rather humourless genre of the kafkaesque so widespread still Explore this journal in contemporary English and German speaking cultures. -

Reader03.Pdf

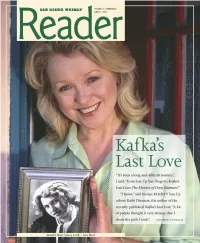

KAFKA’S LAST LOVE Kafka Diamant Tracks Down Kafka’s hairbrush The San Diego Reader, June 12, 2003 By Judith Moore “It’s been a long and difficult journey,” I said, “from Sun Up San Diego to Kafka’s Last Love: The Mystery of Dora Diamant.” “I know,” said former KFMB-TV Sun Up co-host Kathi Diamant, the author of the recently published Kafka’s Last Love. "A lot of people thought it very strange that I chose the path I took. I loved my seven years on Sun Up, and I loved the perqs—the beautiful clothes from Saks Fifth Avenue, the hair and makeup artists who made me look as good as I possibly could every morning. But perhaps it was because on Sun Up that I interviewed so many people about their passions that made me want to follow my own—my longing to find out about Dora Diamant's life and to tell her story. Led by Dora, I found myself entered into a world far from television studios. I found myself spending weeks in Nazi archives in Berlin, and feeling my heart pound when I approached a shelf where there might be some Kafka or Dora treasure. I found myself at a gravesite in Poland and in the room in the Kierling Sanatorium outside Vienna where Kafka died. I often asked myself, ‘Kathi, how did you get here?’” The short version of what took Kathi Diamant from the Channel 8 studios on Kearny Mesa to Prague and Berlin and Athens and London and Jerusalem is that Kathi Diamant was drawn to those places by Dora Diamant. -

Seeing the Middle Ages Through Transnational Lenses in American Comics and Graphic Novels

PALACKÝ UNIVERSITY IN OLOMOUC FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND AMERICAN STUDIES SEEING THE MIDDLE AGES THROUGH TRANSNATIONAL LENSES IN AMERICAN COMICS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS DISSERTATION BY ELIZABETH ALLYN WOOCK SUPERVISED BY PROF. PHDR. MARCEL ARBEIT, DR. OLOMOUC, CZECH REPUBLIC MARCH 2020 1 I, Elizabeth Allyn Woock declare that this dissertation and the work presented in it are my own and have been generated by me as the result of my own original research. I confirm that where I have consulted and quoted from the published work of others, this is always clearly attributed. I have acknowledged all sources of help in bibliography. Part of the research for this dissertation was funded by two grant projects: IGA_FF_2019_037 “Youth literature in British and American culture: criteria, forms, and genres (Literatura pro dospívající mládež v anglické a americké kultuře: kritéria, formy, žánry) in 2019, and IGA_FF_2018_037 “From literature to film, television series and comics: new forms of British and American literary” (Od literatury k filmu, televizní sérii a komiksu: nové podoby děl anglické a americké literatury) in 2018. Signed: ___________________________ Date: ___________________________ 2 CONTENTS Contents .............................................................................................................................. 3 Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgments..............................................................................................................