Post-Postmodernism, Neoliberalism, and the Contemporary Novel’S Contract with the Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Road to Hell

The road to hell Cormac McCarthy's vision of a post-apocalyptic America in The Road is terrifying, but also beautiful and tender, says Alan Warner Alan Warner The Guardian, Saturday 4 November 2006 Article history The Road by Cormac McCarthy 256pp, Picador, £16.99 Shorn of history and context, Cormac McCarthy's other nine novels could be cast as rungs, with The Road as a pinnacle. This is a very great novel, but one that needs a context in both the past and in so-called post-9/11 America. We can divide the contemporary American novel into two traditions, or two social classes. The Tough Guy tradition comes up from Fenimore Cooper, with a touch of Poe, through Melville, Faulkner and Hemingway. The Savant tradition comes from Hawthorne, especially through Henry James, Edith Wharton and Scott Fitzgerald. You could argue that the latter is liberal, east coast/New York, while the Tough Guys are gothic, reactionary, nihilistic, openly religious, southern or fundamentally rural. The Savants' blood line (curiously unrepresentative of Americans generally) has gained undoubted ascendancy in the literary firmament of the US. Upper middle class, urban and cosmopolitan, they or their own species review themselves. The current Tough Guys are a murder of great, hopelessly masculine, undomesticated writers, whose critical reputations have been and still are today cruelly divergent, adrift and largely unrewarded compared to the contemporary Savant school. In literature as in American life, success must be total and contrasted "failure" fatally dispiriting. But in both content and technical riches, the Tough Guys are the true legislators of tortured American souls. -

2016 Fiction Longlist Release FINAL

RELEASE: SEPTEMBER 15, 2016 Contact: Sherrie Young 9:30 a.m. EDT National Book Foundation (212) 685-0261 [email protected] 2016 NATIONAL BOOK AWARDS LONGLIST FOR FICTION The ten contenders for the National Book Award for Fiction. New York, NY (September 15, 2016) – The National Book Foundation today announced the Longlist for the 2016 National Book Award for Fiction. Finalists will be revealed on October 13. (Please note that this date was originally set for October 12, but has been changed to acknowledge Yom Kippur.) The Fiction Longlist includes a former National Book Award Winner for Young People’s Literature and two titles by former National Book Award Finalists for Fiction. The list also includes three Pulitzer Prize finalists. One title is currently shortlisted for the 2016 Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction and another was recently selected for Oprah’s Book Club. There is one debut novel on the list. The year’s Longlist is told from and about locations all around the world. Authors hail from and titles explore locations that range from Alaska, New Delhi, Bulgaria, and even a reimagined United States. Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad follows Cora, a fugitive slave, as she escapes the south on a literal underground railroad in a speculative historical fiction that reckons with the true legacy of liberation and escape. In a very different journey, former Pulitzer Prize finalist Lydia Millet’s Sweet Lamb of Heaven follows a mother as she traverses the country with her daughter, fleeing her powerful husband. What Belongs to You, a debut novel by Garth Greenwell, finds its American narrator in Sofia, Bulgaria attempting to reconcile the shame and desire bound up in his own sexuality. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

"On the hole business is very good."-- William Gaddis' rewriting of novelistic tradition in "JR" (1975) Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Thomas, Rainer Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 10:15:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/291833 INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Enthymema XXIII 2019 the Sentence Is Most Important: Styles of Engagement in William T. Vollmann's Fictions

Enthymema XXIII 2019 The Sentence Is Most Important: Styles of Engagement in William T. Vollmann’s Fictions Christopher K. Coffman Boston University Abstract – William T. Vollmann frequently asserts that his ideal reader will appreci- ate the functionality and beauty of his sentences. This article begins by taking such claims seriously, and draws on both literary and rhetorical stylistics to explore some of the many ways that his texts answer to his intention to find “the right sentence for the right job.” In particular, this article argues that Vollmann’s stylistic decisions are most notable when they most directly satisfy his effort to produce texts that fos- ter empathetic knowledge, serve truth, resist abusive power, and encourage charita- ble action. Extended close analyses of passages from an early and from a mid-ca- reer text (The Rainbow Stories and Europe Central) illustrate Vollmann’s con- sistency across two decades of his career regarding choices in the areas of figura- tion (including schemes and tropes of comparison, repetition, balance, naming, and amplification), grammar, deixis, allusion, and other compositional strategies. Partic- ular attention is paid to passages that display the stylistic mechanisms underlying Vollmann’s negotiation of his texts’ moral qualities, including both the moral con- tent of the worlds represented in the texts, and the moral responsibility the texts bear with regard to their audience. The results of my analyses demonstrate that Vollmann typically prioritizes openness, critique, and dialogue not only in terms of incident and character, but also on the scale of the phrase, clause, and sentence. Ultimately, this article shows how Vollmann’s sentences serve his declared inten- tions and allow readers to recognize compatibilities between Vollmann’s works and the characteristic features of post-postmodernist writing in general. -

A NEW DIRECTION for CHICK LIT by Rachel

ABSTRACT CONSCIOUSNESS-RAISING: A NEW DIRECTION FOR CHICK LIT by Rachel R. Rode Schaefer Focusing on novels published outside of the popular market, this thesis seeks to draw attention to work being published under the label of chick lit that subverts standard chick lit genre conventions. While much work has been and is being done that concentrates on popular market chick lit, such as Helen Fielding’s Bridget Jones’s Diary (1996) and Candace Bushnell’s Sex and the City (1996), only cursory attention is being given to transnational, minority, and religious chick lit. This thesis considers chick lit within the larger history of women’s writing in order to contextualize the genre. Since chick lit has been connected to both feminism and post-feminism in its origins, consideration of this genre as a feminist genre focuses attention on how chick lit functions as a consciousness-raising genre. CONSCIOUSNESS-RAISING: A NEW DIRECTION FOR CHICK LIT A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University In partial fulfillment of Master of Arts Department of English by Rachel R. Rode Schaefer Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2015 Advisor_________________________________ Dr. Madelyn Detloff Reader__________________________________ Dr. Mary Jean Corbett Reader__________________________________ Dr. Theresa Kulbaga © Rachel R. Rode Schaefer 2015 Table of Contents Introduction: Reading Chick Lit as Consciousness-Raising Novel ................................................ 1 Project Summary ........................................................................................................................ -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Form and Ideology in Jonathan Franzen's Fiction

Universidad de Córdoba Departamento de Filología Inglesa y Alemana The Romance of Community: Form and Ideology in Jonathan Franzen’s Fiction Tesis doctoral presentada por Jesús Blanco Hidalga Dirigida por Dr. Julián Jiménez Heffernan Dra. Paula Martín Salván VºBº Directores de la Tesis Doctoral Fdo. El Doctorando Dr. Julián Jiménez Heffernan Jesús Blanco Hidalga Dra. Paula Martín Salván Córdoba, 2015 TITULO: The Romance of Community: Form and Ideology in Jonathan Frazen's Fiction AUTOR: Jesús Blanco Hidalga © Edita: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Córdoba. 2015 Campus de Rabanales Ctra. Nacional IV, Km. 396 A 14071 Córdoba www.uco.es/publicaciones [email protected] Index: Description of contents: Aim, scope and structure of this work………………………...5 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………….14 1.1. Justification of this work…………………………………………………...14 1.2. The narrative of conversion………………………………………………..15 1.3. Theoretical coordinates and critical procedures…………………………...24 1.3.1. Socially symbolic narratives……………………………….……..26 1.3.2. The question of realism: clarifying terms………………….……..33 1.3.3. Realism, contingency and the weight of inherited forms………...35 1.3.4. Realism, totality and late capitalism……………………….……..39 1.3.5. The problem of perspective………………………………………43 1.4. Community issues………………………………………………………….48 2. The critical reception of Jonathan Franzen’s novels………………………………...53 2.1. Introduction: a controversial novelist.……………………………………..53 2.2. Early fiction: The Twenty-Seventh City and Strong Motion……………….56 2.3. The Corrections and the Oprahgate……………………………………….60 2.4. Hybrid modes and postmodern uncertainties……………………...………66 2.5. The art of engagement…..………………………………………...……….75 2.6. Freedom as the latest Great American Novel?.............................................81 2.7. Latest critical references…………………………………………………...89 2.8. -

Suburbs in American Literature

FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA UNIVERZITY PALACKÉHO KATEDRA ANGLISTIKY A AMERIKANISTIKY SUBURBS IN AMERICAN LITERATURE A STUDY OF THREE SELECTED SUBURBAN NOVELS (Bakalářská práce) Autor: Lucie Růžičková Anglická filologie- Žurnalistika Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, PhD. OLOMOUC 2013 Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Suburbs in American Literature A Study of Three Selected Suburban Novels (Diplomová práce) Autor: Lucie Růžičková Studijní obor: Anglická a žurnalistika Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D. Počet stran (podle čísel): Počet znaků: Olomouc 2013 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla úplný seznam citované a použité literatury. V Olomouci dne 25.4. 2013 ………………………… I would like to say thank you to Mgr. Jiří Flajšar, Ph.D., who has been very patient with me and has been of a great support and help while supervising my thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS: 1. Introduction ………………………………………………………. 3 2. Suburbs – The Terminology ……………………………………… 5 2.1 American Suburbs ……………………………………………. 5 2.2 Brief history of American suburbia …………………………... 6 2.3 Suburban novel and well-know authors ……………………… 7 3. John Updike ………………………………………………………. 10 3.1 Biography ……………………………………………………... 10 3.2 Bibliography …………………………………………………... 11 4. Rabbit, Run – The Analysis ………………………………………. 13 4.1 The plot ……………………………………………………….. 13 4.2 The portrait of suburb ………………………………………… 16 4.3 Characters and their relationships …………………………….. 17 4.3.1 Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom ……………………………….. 17 4.3.2 Janice Angstrom …………………………………………. 18 4.3.3 Ruth Leonard …………………………………………….. 19 5. Richard Ford ……………………………………………………….. 21 5.1 Biography ……………………………………………………… 21 5.2 Bibliography …………………………………………………… 22 6. The Sportswriter - The Analysis …………………………………… 24 6.1 The plot ………………………………………………………… 24 6.2 The portrait of suburb ………………………………………….. 27 6.3 Characters and their relationships ……………………………… 28 6.3.1 Frank Bascombe …………………………………………. -

Ambivalence in the Fiction of Jonathan Franzen and Amitav Ghosh

Durham E-Theses The View from Somewhere: Ambivalence in The Fiction of Jonathan Franzen and Amitav Ghosh CHOU, MEGUMI,GRACE How to cite: CHOU, MEGUMI,GRACE (2019) The View from Somewhere: Ambivalence in The Fiction of Jonathan Franzen and Amitav Ghosh, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13619/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The View from Somewhere: Ambivalence in The Fiction of Jonathan Franzen and Amitav Ghosh Megumi Grace Chou Submitted for: M.A. by Research Department of English Studies, University of Durham November 2019 Thesis Abstract This thesis seeks to understand experiential ambivalence in the later works of American novelist Jonathan Franzen (1959-) and Indian writer of English Amitav Ghosh (1956-). Both authors note that there is an uncertainty and resistance inherent to our experience of the world, as rooted in contested notions of the past. -

View to More General Losses and the Attempts by the Subjects and the Poet to Navigate Those Events

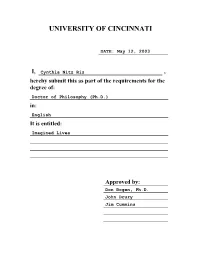

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 12, 2003 I, Cynthia Nitz Ris , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in: English It is entitled: Imagined Lives Approved by: Don Bogen, Ph.D. John Drury Jim Cummins IMAGINED LIVES A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English Composition and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2003 by Cynthia Nitz Ris B.A., Texas A&M University, 1978 J.D., University of Michigan, 1982 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Don Bogen, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation consists of a collection of original poetry by Cynthia Nitz Ris and a critical essay regarding William Gaddis’s novel A Frolic of His Own. Both sections are united by reflecting the difficulties of utilizing past experiences to produce a fixed understanding of lives or provide predictability for the future; all lives and events are in flux and in need of continual reimagining or recharting to provide meaning. The poetry includes a variety of forms, including free verse, sonnets, blank verse, sapphics, rhymed couplets, stanzaic forms including mad-song stanzas and rhymed tercets, variations on regular forms, and nonce forms. Poems are predominantly lyrical expressions, though many employ narrative strategies to a greater or lesser degree. The first of four units begins with a long-poem sequence which serves as prologue by examining general issues of loss through a Freudian lens. -

BA North American Studies Summer 2021

Datum: 04.03.2021 Semester: Sommer 2021 Seite 1 von 42 BA-Studiengang I. Kerncurriculum B.AS.101: Analysis and Interpretation 4508505 Introduction to the Study of American Literature and Culture Einführung SWS: 2; Anz. Teiln.: 15 Künnemann, Vanessa Di 12:00 - 14:00 Raum: Jacob-Grim SEP 0.244 , wöchentlich Von: 13.04.2021 Bis: 13.07.2021 Mo 12:00 - 14:00Portfolio am: 02.08.2021 Bemerkung zum Termin: Stand Februar 2021:Die Prüfungsleistung dieses Kurses ist im SoSe auf- grund der Corona-Epidemie voraussichtlich nicht eine Präsenzklausur am 13.07.21, sondern ein Portfolio aus den Seminarleistungen und einem Take Home Exam (statt Klausur) mit Abgabe des Take Home Exam-An- teils der Prüfungsleistung am 02.08.21 nach zweiwöchiger Bearbeitungs- zeit. Updates werden im Kurs bekannt gegegeben. Prüfungsleistung: Portfolio aus Seminarleistungen und Take Home Exam Module zum Termin: B.EP.01.1A: Grundlagen der Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft . B.EP.01.1B: Grundlagen der Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft . Di 12:00 - 14:00Prüfungsvorleistung am: 13.07.2021 Module zum Termin: B.AS.101.PrVor: Introduction to the Study of American Literature and Culture . Di 12:00 - 14:00Klausur am: 13.07.2021 Bemerkung zum Termin: Given the pandemic, the Prüfungsleistung will probably not be an exam (Klausur), but a Portfolio (consisting of class requirements (Seminarlei- stungen) and a Take Home Exam) in the summer term. Please pay atten- tion to announcements at the beginning of class!. Module zum Termin: B.EP.01.1A: Grundlagen der Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft . B.EP.01.1B: Grundlagen der Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft . Module B.EP.01.1A: Grundlagen der Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft B.EP.01.1B: Grundlagen der Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft B.AS.101.PrVor: Introduction to the Study of American Literature and Culture Kommentar This class is designed to introduce students to standard concepts, methods, and re- sources of (American) literary and cultural studies. -

Ali Dissertation Revised

Recuperating Deliberation in Early-Postmodern US Fiction by Alistair M. C. Chetwynd A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor Gregg D. Crane, Chair Professor Patricia S. Yaeger, Chair (Deceased) Professor Sarah Buss Professor Jonathan E. Freedman Associate Professor Gillian C. White Acknowledgments This project took an aeon, and first thanks are equally to the English department at the University of Michigan for time and money, and my family and friends for never actually saying out loud that I should give it up and do something easier and more useful with my life. I’m also extremely grateful to each of my committee for stepping in to help me work on something a long way from any of their own academic interests. I really miss Patsy Yaeger: in particular her enthusiasm about getting to read bits of what she called a “weird” and “wonky” project. I’m grateful to her for feedback on sentence-level writing and the excellent, frequent marginal comment “Where’s The Joy???” Gregg Crane very helpfully took over after Patsy’s death, and his exhortations to be more precise, especially in talking about the relationship between fictions and philosophies, were always energizing: only Danny Hack’s Novel Theory course pushed me more forcefully in the directions my PhD work finally took than Gregg’s 20-second aside about how useful he found early pragmatism for thinking about literature, back in the second or third class session I sat in at Michigan.