Ali Dissertation Revised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walt Whitman, Where the Future Becomes Present, Edited by David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson

7ALT7HITMAN 7HERETHE&UTURE "ECOMES0RESENT the iowa whitman series Ed Folsom, series editor WALTWHITMAN WHERETHEFUTURE BECOMESPRESENT EDITEDBYDAVIDHAVENBLAKE ANDMICHAELROBERTSON VOJWFSTJUZPGJPXBQSFTTJPXBDJUZ University of Iowa Press, Iowa City 52242 Copyright © 2008 by the University of Iowa Press www.uiowapress.org All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Design by Richard Hendel No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. All reasonable steps have been taken to contact copyright holders of material used in this book. The publisher would be pleased to make suitable arrangements with any whom it has not been possible to reach. The University of Iowa Press is a member of Green Press Initiative and is committed to preserving natural resources. Printed on acid-free paper issn: 1556–5610 lccn: 2007936977 isbn-13: 978-1-58729–638-3 (cloth) isbn-10: 1-58729–638-1 (cloth) 08 09 10 11 12 c 5 4 3 2 1 Past and present and future are not disjoined but joined. The greatest poet forms the consistence of what is to be from what has been and is. He drags the dead out of their coffins and stands them again on their feet .... he says to the past, Rise and walk before me that I may realize you. He learns the lesson .... he places himself where the future becomes present. walt whitman Preface to the 1855 Leaves of Grass { contents } Acknowledgments, ix David Haven Blake and Michael Robertson Introduction: Loos’d of Limits and Imaginary Lines, 1 David Lehman The Visionary Whitman, 8 Wai Chee Dimock Epic and Lyric: The Aegean, the Nile, and Whitman, 17 Meredith L. -

The Road to Hell

The road to hell Cormac McCarthy's vision of a post-apocalyptic America in The Road is terrifying, but also beautiful and tender, says Alan Warner Alan Warner The Guardian, Saturday 4 November 2006 Article history The Road by Cormac McCarthy 256pp, Picador, £16.99 Shorn of history and context, Cormac McCarthy's other nine novels could be cast as rungs, with The Road as a pinnacle. This is a very great novel, but one that needs a context in both the past and in so-called post-9/11 America. We can divide the contemporary American novel into two traditions, or two social classes. The Tough Guy tradition comes up from Fenimore Cooper, with a touch of Poe, through Melville, Faulkner and Hemingway. The Savant tradition comes from Hawthorne, especially through Henry James, Edith Wharton and Scott Fitzgerald. You could argue that the latter is liberal, east coast/New York, while the Tough Guys are gothic, reactionary, nihilistic, openly religious, southern or fundamentally rural. The Savants' blood line (curiously unrepresentative of Americans generally) has gained undoubted ascendancy in the literary firmament of the US. Upper middle class, urban and cosmopolitan, they or their own species review themselves. The current Tough Guys are a murder of great, hopelessly masculine, undomesticated writers, whose critical reputations have been and still are today cruelly divergent, adrift and largely unrewarded compared to the contemporary Savant school. In literature as in American life, success must be total and contrasted "failure" fatally dispiriting. But in both content and technical riches, the Tough Guys are the true legislators of tortured American souls. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

"On the hole business is very good."-- William Gaddis' rewriting of novelistic tradition in "JR" (1975) Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Thomas, Rainer Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 10:15:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/291833 INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Philosophical Fiction? on J. M. Coetzee's Elizabeth Costello

Philosophical Fiction? On J. M. Coetzee’s Elizabeth Costello Robert Pippin University of Chicago i he modern fate of the ideal of the beautiful is deeply intertwined with the beginnings of European aesthetic modernism. More specifically, from the point of view of modernism, commitment to the ideal of the beautiful is often understood to be both Tirrelevant and regressive. This claim obviously requires a gloss on “modernity” and “modern- ism.” Here is a conventional view. European modernism in the arts can be considered a reaction to the form of life coming into view in the mid-nineteenth century as the realization of early Enlightenment ideals: that is, the supreme cognitive authority of modern natural science, a new market economy based on the accumulation of private capital, rapid urbanization and industri- alization, ostensibly democratic institutions still largely controlled by elites, the privatization of religion and so the secularization of the public sphere. The modernist moment arose from some sense that this form of life was so unprecedented in human history that art’s very purpose or rationale, its mode of address to an audience, had to be fundamentally rethought. Nothing about the purpose or value of art, as it had been understood, could be taken for granted any longer, and the issue was: what kind of art, committed to what ideal, could be credible in such a world (if any)? A response to such a development was taken by some to require a novelty, experimentation and formal radicality so extreme as to seem unintelligible to its “first responders.” Modernism was to be an anti-Romanticism, rejecting lyrical expression of the inner in favor of impersonal- ity, or of multiple, fractured authorial personae, attempting an ironic distancing, experimental 2 republics of letters innovation, and, in so-called high modernism, assuming an elite position, sometimes with mul- tiple, obscure allusions, defiantly resistant to commercialization or a public role. -

The Post-Postmodern Aesthetics of John Fowles Claiborne Johnson Cordle

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 5-1981 The post-postmodern aesthetics of John Fowles Claiborne Johnson Cordle Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Recommended Citation Cordle, Claiborne Johnson, "The post-postmodern aesthetics of John Fowles" (1981). Master's Theses. Paper 444. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE POST-POSTMODERN AESTHETICS OF JOHN FOWLES BY CLAIBORNE JOHNSON CORDLE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF ~.ASTER OF ARTS ,'·i IN ENGLISH MAY 1981 LTBRARY UNIVERSITY OF RICHMONl:» VIRGINIA 23173 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION . p . 1 CHAPTER 1 MODERNISM RECONSIDERED . p • 6 CHAPTER 2 THE BREAKDOWN OF OBJECTIVITY . p • 52 CHAPTER 3 APOLLO AND DIONYSUS. p • 94 CHAPTER 4 SYNTHESIS . p . 102 CHAPTER 5 POST-POSTMODERN HUMANISM . p . 139 ENDNOTES • . p. 151 BIBLIOGRAPHY . • p. 162 INTRODUCTION To consider the relationship between post modernism and John Fowles is a task unfortunately complicated by an inadequately defined central term. Charles Russell states that ... postmodernism is not tied solely to a single artist or movement, but de fines a broad cultural phenomenon evi dent in the visual arts, literature; music and dance of Europe and the United States, as well as in their philosophy, criticism, linguistics, communications theory, anthropology, and the social sciences--these all generally under thp particular influence of structuralism. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Abubakr Bin Ṭufayl's Ḥayy Bin Yaqzān and Its Reception in Early Modern

Abubakr bin Ṭufayl’s Ḥayy bin Yaqzān and its Reception in Early Modern England by Muhammad I.U. Sid-Ahmad Ismail A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy submitted to the Graduate Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright by Muhammad I.U. Sid-Ahmad (2014) Abubakr bin Ṭufayl’s Ḥayy bin Yaqzān and its Reception in Early Modern England Muhammad I.U. Sid-Ahmad Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto 2014 Abstract This study of Abubakr bin Ṭufayl’s Ḥayy bin Yaqzān and its reception in early modern England aims to determine the extent and nature of John Milton’s, John Locke’s and Daniel Defoe’s engagement of Ḥayy. I begin with historical research that offers the interpretative contexts upon which my comparative analyses rely. The dissertation begins with a study of seventeenth-century England where Ḥayy was received and twelfth-century Morocco where it was written, correcting misunderstandings in recent studies of the meaning and role of Ḥayy. In Chapter Two, I argue that Milton’s representation of Adam’s awakening in Book VIII of Milton’s Paradise Lost may have been influenced by Ḥayy. I further suggest considering whether Milton had access to other medieval Islamic sources, particularly Islamic stories of ascent. The shared elements suggest considering these stories part of a common cycle. As for John Locke, my analysis corrects earlier suggestions that his Essay Concerning Humane Understanding and Ḥayy are in agreement. I show that Locke in fact disagreed with the claims made in Ḥayy. -

Aalborg Universitet Dialogues on Poetry Mediatization and New

Aalborg Universitet Dialogues on Poetry Mediatization and New Sensibilities Ringgaard, Dan; Kjerkegaard, Stefan Publication date: 2017 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Ringgaard, D., & Kjerkegaard, S. (Eds.) (2017). Dialogues on Poetry: Mediatization and New Sensibilities. (1. ed.) Aalborg Universitetsforlag. Studies in Contemporary Poetry / Studier i samtidslyrik, No. 4 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: June 16, 2020 DIALOGUES ON Mediatization and New Sensibilities Edited by Stefan Kjerkegaard Dan Ringgaard DIALOGUES ON Mediatization and New Sensibilities Edited by Stefan Kjerkegaard Dan Ringgaard DIALOGUES ON POETRY Mediatization and New Sensibilities Redaktører Stefan Kjerkegaard og Dan Ringgaard OA-udgave © Redaktørerne og Aalborg Universitetsforlag, 2017 4. udgivelse i serien Studies in Contemporary Poetry / Studier i samtidslyrik Serieredaktører: Professor dr.phil. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

Forms of Frustration: Unrest and Unfulfillment in American Literature After 1934

Forms of Frustration: Unrest and Unfulfillment in American Literature after 1934 Ethan Charles Reed Canandaigua, NY M.A., University of Virginia, 2016 B.A., Brown University, 2012 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English University of Virginia May 2019 i Abstract This dissertation offers an account of what the condition we call frustration has meant and might mean for modern and contemporary literary study. Building on theories of affect as they relate to race, class, and gender in American literature, I focus in particular upon the articulation of feeling in the face of systemic injustice within recent US literary history. Building on recent scholarship suggesting that feeling gives structure to cultural formations, I argue that a history of unrest in America reveals a pattern of artistic response, a sensibility, precipitated by specific historical moments but translated into aesthetic practice through a stable constellation of affective structures. This constellation, I argue, is an affective situation governed not by anger, despair, or hope, but by frustration as a persistent structural condition. To this end, I examine continuities between politically-engaged aesthetic projects from three periods of discontent in American history: radical journals like Partisan Review in the 1930s; the revolutionary poetry of the Black Arts Movement in the 60s; and contemporary revenge-driven novels drawing from the Red Power movement. In pursuing this inquiry, my work attempts to offer an account of frustration that bridges the gap between specific articulation and historical pattern. Where Sianne Ngai uses an “ugly feeling” (like irritation) to investigate how Nella Larsen’s novel Quicksand articulates racial injustice, I attempt to trace a larger historical trajectory of a radical sensibility in America. -

Leslie Marmon Silko's Almanac of the Dead

Writing Counter-Histories of the Americas: Leslie Marmon Silko’s Almanac Of The Dead A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy University of Wollongong by Glenda Moylan-Brouff, B. A. Hons. School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications 2004 i This thesis is all my own work and has not been submitted for a degree to any other institution or university. Glenda Moylan-Brouff December, 2004. ii Contents Abstract i Acknowledgements ii Introduction 1 Chapter One: Re-evaluating Dominant Representations of Geronimo and the Apache Nation; Mapping the Politics of Colonial 14 Recuperation Chapter Two: Re-figuring Geronimo: Story/History and the Politics of Cultural Difference 71 Chapter Three: Photography and the Politics of Visual Representation 122 Chapter Four: Native American Interventions in the Politics of Photographic Representation 168 Chapter Five: Writing Indigenous Histories: The Politics of Genre and Cultural Difference in Leslie Marmon Silko’s Almanac Of The Dead 218 Chapter Six: Re-articulating the Politics of Native American Prophecy: Temporality and Resistance in Leslie Marmon Silko’s Almanac Of The Dead 261 Conclusion 308 Appendix 315 Works Cited 327 iii Abstract Writing Counter-histories of the Americas: Leslie Marmon Silko’s Almanac Of The Dead This thesis stages a critical interrogation of the colonial politics that have shaped and continue to shape representations of Native Americans in a North American context. This critical interrogation is based on a reading of Leslie Marmon Silko's landmark text Almanac Of The Dead. I argue that Silko's deployment of Native American counter-discourses of history and story-telling contests Eurocentric epistemologies and ideologies and their entrenched colonial relations of power/knowledge. -

View to More General Losses and the Attempts by the Subjects and the Poet to Navigate Those Events

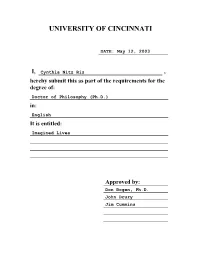

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 12, 2003 I, Cynthia Nitz Ris , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in: English It is entitled: Imagined Lives Approved by: Don Bogen, Ph.D. John Drury Jim Cummins IMAGINED LIVES A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English Composition and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2003 by Cynthia Nitz Ris B.A., Texas A&M University, 1978 J.D., University of Michigan, 1982 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Don Bogen, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation consists of a collection of original poetry by Cynthia Nitz Ris and a critical essay regarding William Gaddis’s novel A Frolic of His Own. Both sections are united by reflecting the difficulties of utilizing past experiences to produce a fixed understanding of lives or provide predictability for the future; all lives and events are in flux and in need of continual reimagining or recharting to provide meaning. The poetry includes a variety of forms, including free verse, sonnets, blank verse, sapphics, rhymed couplets, stanzaic forms including mad-song stanzas and rhymed tercets, variations on regular forms, and nonce forms. Poems are predominantly lyrical expressions, though many employ narrative strategies to a greater or lesser degree. The first of four units begins with a long-poem sequence which serves as prologue by examining general issues of loss through a Freudian lens.