Download Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Road to Hell

The road to hell Cormac McCarthy's vision of a post-apocalyptic America in The Road is terrifying, but also beautiful and tender, says Alan Warner Alan Warner The Guardian, Saturday 4 November 2006 Article history The Road by Cormac McCarthy 256pp, Picador, £16.99 Shorn of history and context, Cormac McCarthy's other nine novels could be cast as rungs, with The Road as a pinnacle. This is a very great novel, but one that needs a context in both the past and in so-called post-9/11 America. We can divide the contemporary American novel into two traditions, or two social classes. The Tough Guy tradition comes up from Fenimore Cooper, with a touch of Poe, through Melville, Faulkner and Hemingway. The Savant tradition comes from Hawthorne, especially through Henry James, Edith Wharton and Scott Fitzgerald. You could argue that the latter is liberal, east coast/New York, while the Tough Guys are gothic, reactionary, nihilistic, openly religious, southern or fundamentally rural. The Savants' blood line (curiously unrepresentative of Americans generally) has gained undoubted ascendancy in the literary firmament of the US. Upper middle class, urban and cosmopolitan, they or their own species review themselves. The current Tough Guys are a murder of great, hopelessly masculine, undomesticated writers, whose critical reputations have been and still are today cruelly divergent, adrift and largely unrewarded compared to the contemporary Savant school. In literature as in American life, success must be total and contrasted "failure" fatally dispiriting. But in both content and technical riches, the Tough Guys are the true legislators of tortured American souls. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

"On the hole business is very good."-- William Gaddis' rewriting of novelistic tradition in "JR" (1975) Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Thomas, Rainer Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 10:15:18 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/291833 INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

Women and the Presidency

Women and the Presidency By Cynthia Richie Terrell* I. Introduction As six women entered the field of Democratic presidential candidates in 2019, the political media rushed to declare 2020 a new “year of the woman.” In the Washington Post, one political commentator proclaimed that “2020 may be historic for women in more ways than one”1 given that four of these woman presidential candidates were already holding a U.S. Senate seat. A writer for Vox similarly hailed the “unprecedented range of solid women” seeking the nomination and urged Democrats to nominate one of them.2 Politico ran a piece definitively declaring that “2020 will be the year of the woman” and went on to suggest that the “Democratic primary landscape looks to be tilted to another woman presidential nominee.”3 The excited tone projected by the media carried an air of inevitability: after Hillary Clinton lost in 2016, despite receiving 2.8 million more popular votes than her opponent, ever more women were running for the presidency. There is a reason, however, why historical inevitably has not yet been realized. Although Americans have selected a president 58 times, a man has won every one of these contests. Before 2019, a major party’s presidential debates had never featured more than one woman. Progress toward gender balance in politics has moved at a glacial pace. In 1937, seventeen years after passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, Gallup conducted a poll in which Americans were asked whether they would support a woman for president “if she were qualified in every other respect?”4 * Cynthia Richie Terrell is the founder and executive director of RepresentWomen, an organization dedicated to advancing women’s representation and leadership in the United States. -

Laridae Salisbury University Undergraduate Academic Journal

SALISBURY UNIVERSITY Undergraduate Academic Journal BLACK GIRL M/\G/C Volume 2 – Fall 2020 Salisbury University Offce of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity (OURCA) Enough Is Enough Eric Johnson Jr. (Featured on the Cover) ABSTRACT Racism has led to continuous confict between people since the beginning of time, and it is time for this evil to end – enough is enough. Since the beginning of 2020, we have lost many lives due to COVID-19 and police brutality as the whole world watched. Police brutality is the use of excessive force by an offcer, which can be legally defned as a civil rights violation. Over the years, we have lost many of our citizens and justice was not served. Eric Garner, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbrey … and so many more. The fact that I can fll at least two pages with victims is sickening – enough is enough! The brutality against African Americans this year has spiked to a recent all-time high. The videos of police killings have flled the news and internet – enough is enough. The death of George Floyd was heartbreaking. I personally couldn’t even fnish watching because the video was just so gruesome. All the lives that we have lost this year are heartbreaking – enough is enough. In this moment, the time we are in now, we do not need division. Instead, we need to come together in unity. The purpose of these photos is to show that enough is enough. I believe that one day we will all see the light at the end of this dark tunnel, but we have a long way still to go in order to come together. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Harpercollins Books for the First-Year Student

S t u d e n t Featured Titles • American History and Society • Food, Health, and the Environment • World Issues • Memoir/World Views • Memoir/ American Voices • World Fiction • Fiction • Classic Fiction • Religion • Orientation Resources • Inspiration/Self-Help • Study Resources www.HarperAcademic.com Index View Print Exit Books for t H e f i r s t - Y e A r s t u d e n t • • 1 FEATURED TITLES The Boy Who Harnessed A Pearl In the Storm the Wind How i found My Heart in tHe Middle of tHe Ocean Creating Currents of eleCtriCity and Hope tori Murden McClure William kamkwamba & Bryan Mealer During June 1998, Tori Murden McClure set out to William Kamkwamba was born in Malawi, Africa, a row across the Atlantic Ocean by herself in a twenty- country plagued by AIDS and poverty. When, in three-foot plywood boat with no motor or sail. 2002, Malawi experienced their worst famine in 50 Within days she lost all communication with shore, years, fourteen-year-old William was forced to drop ultimately losing updates on the location of the Gulf out of school because his family could not afford the Stream and on the weather. In deep solitude and $80-a-year-tuition. However, he continued to think, perilous conditions, she was nonetheless learn, and dream. Armed with curiosity, determined to prove what one person with a mission determination, and a few old science textbooks he could do. When she was finally brought to her knees discovered in a nearby library, he embarked on a by a series of violent storms that nearly killed her, daring plan to build a windmill that could bring his she had to signal for help and go home in what felt family the electricity only two percent of Malawians like complete disgrace. -

Complete Catalog 7.6 MB

NEW WORLD LIBRARY WINTER–SPRING 2021 H J KRAMER ECKHART TOLLE EDITIONS NATARAJ PUBLISHING NAMASTE PUBLISHING Contents New Titles Primitive Mythology 2 Joseph Campbell 30 Three Simple Lines 3 Animals 32 Sacred Hags Oracle 4 Business & Prosperity 38 Pause. Breathe. Choose. 5 Celtic Studies 41 Be You, Only Better 6 Children’s 42 Becoming an Empowered Empath 7 Current Affairs / Social Change 43 Being Better 8 Eastern Philosophy 44 Go Big Now 9 Gift 48 Write a Poem, Save Your Life 10 Health & Wellness 49 The Full Spirit Workout 11 Literature, Writing & Creativity 55 Asking for a Pregnant Friend 12 Native American 60 Beyond Medicine 13 Parenting 61 Healing with Nature 14 Personal Growth 63 Permission Granted 15 Psychology & Philosophy 84 Oriental Mythology 16 Religion 88 Integrated Dog Training 17 Spanish Language 90 Women’s Interest 92 Backlist Audio 94 Bestsellers 18 Recently Published Titles 20 About New World Library 96 Eckhart Tolle 24 Academic Examination and Desk Copies 96 Shakti Gawain 26 Order Form 97 Dan Millman 28 Distribution and Contact Information 98 Primitive Mythology The Masks of God, Volume 1 Joseph Campbell Praise for The Masks of God: “The most comprehensive and the most imaginative treatment we have of a subject that sooner or later must claim every serious reader’s attention.” [ — New York Times ] • The first volume in Campbell’s monumental four-volume Masks of God series, originally published in 1959 by Viking and now revised with up-to-date science • Replaces the Penguin paperback edition of Primitive Mythology, which has sold over 215,000 copies since 1991 • The Masks of God titles have sold over 850,000 copies since 1991 and millions more since their original publication in the AVAILABLE IN DECEMBER late 1950s and early 1960s Mythology • $29.95 • Hardcover • This new hardcover Collected Works of Joseph Campbell 528 pp. -

Body, Speech and Mind: Negotiating Meaning and Experience at a Tibetan Buddhist Center

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Anthropology Theses Department of Anthropology 12-2009 Body, Speech and Mind: Negotiating Meaning and Experience at a Tibetan Buddhist Center Amanda S. Woomer Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Woomer, Amanda S., "Body, Speech and Mind: Negotiating Meaning and Experience at a Tibetan Buddhist Center." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/anthro_theses/32 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BODY, SPEECH AND MIND: NEGOTIATING MEANING AND EXPERIENCE AT A TIBETAN BUDDHIST CENTER by AMANDA S. WOOMER Under the Direction of Dr. Emanuela Guano ABSTRACT Examining an Atlanta area Tibetan Buddhist center as a symbolic and imagined border- land space, I investigate the ways that meaning is created through competing narratives of spiri- tuality and “culture.” Drawing from theories of borderlands, cross-cultural interaction, narratives, authenticity and material culture, I analyze the ways that non-Tibetan community members of the Drepung Loseling center navigate through the interplay of culture and spirituality and how this interaction plays into larger discussions of cultural adaptation, appropriation and representa- tion. Although this particular Tibetan Buddhist center is only a small part of Buddhism’s exis- tence in the United States today, discourses on authenticity, representation and mediated under- standing at the Drepung Loseling center provide an example of how ethnic, social, and national boundaries may be negotiated through competing – and overlapping – narratives of culture. -

Party Women and the Rhetorical Foundations of Political Womanhood

“A New Woman in Old Fashioned Times”: Party Women and the Rhetorical Foundations of Political Womanhood A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Emily Ann Berg Paup IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, Advisor December 2012 © Emily Ann Berg Paup 2012 i Acknowledgments My favorite childhood author, Louis May Alcott, once wrote: “We all have our own life to pursue, our own kind of dream to be weaving, and we all have the power to make wishes come true, as long as we keep believing.” These words have guided me through much of my life as I have found a love of learning, a passion for teaching, and an appreciation for women who paved the way so that I might celebrate my successes. I would like to acknowledge those who have aided in my journey, helped to keep me believing, and molded me into the scholar that I am today. I need to begin by acknowledging those who led me to want to pursue a career in higher education in the first place. Dr. Bonnie Jefferson’s The Rhetorical Tradition was the first class that I walked into during my undergraduate years at Boston College. She made me fall in love with the history of U.S. public discourse and the study of rhetorical criticism. Ever since the fall of 2002, Bonnie has been a trusted colleague and friend who showed me what a passion for learning and teaching looked like. Dr. -

Download Issue

'i: 911 i" Virtual History An Intimate ALTERNATIVESAND COUNTERFACTUALS History of Killing EDITZBBY NIALL FERGUSON FACETO FACEKILLING IN 2OTHCENTURY WARFARE JOANNA BOORKE I~~~Bc~-:~i::: i::::;:: i:: i:: : - ;- :: : : - ;:i --- I'---a~E_ ~~:History des9~~1- I~by~eYeryhist0rian..,:!' team of historians~~ ~~fO'c~· venre asenes a~ "' IIIJLIIUIUe~~,mi*l·nlnml ce~ury:turningpeints.8 ~un~. -a·--PC~~n~·:nn~,,,l, : nsih, Tnlnnmnb ~~"l":"LUR""I:nl'uI rlr, Y,,, lli1~61L1~11 a or:nusslas:war - Duel The Sword and ALEXANDERHAMILTON, AARON BURR the Shield ANDTHE FUTUREOF AMERICA THE MITROKHINARCHIVE AND THOMASFLEMING THESECRET HISTORY OFTHE KGB CHRISTOPHER ANDREW AND VASILI MITROKHIN THOMAS FLEMINGI :::·j~:-~~ ---··-·-- ····-: ···~: ···~~-·I ~~~:·-·~·-· I c ~"~'` "e~ ,revea~lnD· andrelevant...it remindf~ men:~power;and P~~~ ~~Sed humanrl,;,:,~~~ --~~~~~mTade~lPilitrakhin·the KGB:asu,- ~P[aCe-I'~KennethT.Jacksonl·IU··`l:l~~ _ ~rjppe~~~ i~ Histbry:andSocial Sciencesl -I:~,=_S--L~lhP~~~k Review :=i:::- -VYIUI"U'PUIIIIIIIIV a ~A~IONA~BES~'ELLER~-~ 5~1n,ll ~a~p~~f~~ 1 I g ~ I a;~ ss1CI1I Igs 8 Some~p~o~l~ithink :Mexico City was the ii0ngestj Mmp!:)lI,ever,:'made.l BUtJ Ust i: gett ing Ithe~:~as toug her. As a kid, I Was~in:~::gang.·. in trouble With:the:law. ifnot ior a c~i:id~n·5:c0~iud9k Who saw more in:me:'-'who knew that when kids are supported by caring adults, they can learn from their mistakes - I could have landed in prison. He sent me to an alternative school where people helped me get on track. k The children's court gave me the chance to land on:my feet. -

Belva Ann Lockwood, Feminist Lawyer

Syracuse University SURFACE The Courier Libraries 7-1971 Belva Ann Lockwood, Feminist Lawyer Sylvia G. L. Dannett Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc Part of the American Studies Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Dannett, Sylvia G. L. "Belva Ann Lockwood, Feminist Lawyer." The Courier 8.4 (1971): 40-50. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Courier by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • The old Phillipsburg, New Jersey passenger station on the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad. 1913 THE COURIER SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY ASSOCIATES VOLUME VIII, NUMBER 4 JULY, 1971 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Geddes, New York, 1829-1935: Letters of George Owens Richard G. Case 3 "I Am Satisfied With What 1 Have Done": Collis P. Huntington, 19th Century Entrepreneur Alice M. Vestal 20 The D.L. & W. -A Nostalgic Glimpse 35 The Satirical Rogue Once More: Robert Francis on Poets and Poetry 36 Belva Ann Lockwood, Feminist Lawyer Sylvia G. L. Dannett 40 Open for Research ... Notes on Collections 51 News of Library Associates 54 Belva Ann Lockwood. Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society, New York City 40 Belva Ann Lockwood, Feminist Lawyer by Sylvia G. L. Dannett Mrs. Dannett has been pursuing research in the University Archives on Belva Ann Lockwood, 1857 graduate of Genesee College and recipient of a master's degree in 1872 and an honorary LL.D. -

View to More General Losses and the Attempts by the Subjects and the Poet to Navigate Those Events

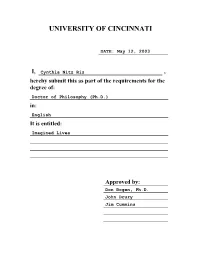

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 12, 2003 I, Cynthia Nitz Ris , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in: English It is entitled: Imagined Lives Approved by: Don Bogen, Ph.D. John Drury Jim Cummins IMAGINED LIVES A dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D.) in the Department of English Composition and Comparative Literature of the College of Arts and Sciences 2003 by Cynthia Nitz Ris B.A., Texas A&M University, 1978 J.D., University of Michigan, 1982 M.A., University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Don Bogen, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation consists of a collection of original poetry by Cynthia Nitz Ris and a critical essay regarding William Gaddis’s novel A Frolic of His Own. Both sections are united by reflecting the difficulties of utilizing past experiences to produce a fixed understanding of lives or provide predictability for the future; all lives and events are in flux and in need of continual reimagining or recharting to provide meaning. The poetry includes a variety of forms, including free verse, sonnets, blank verse, sapphics, rhymed couplets, stanzaic forms including mad-song stanzas and rhymed tercets, variations on regular forms, and nonce forms. Poems are predominantly lyrical expressions, though many employ narrative strategies to a greater or lesser degree. The first of four units begins with a long-poem sequence which serves as prologue by examining general issues of loss through a Freudian lens.