Body, Speech and Mind: Negotiating Meaning and Experience at a Tibetan Buddhist Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laridae Salisbury University Undergraduate Academic Journal

SALISBURY UNIVERSITY Undergraduate Academic Journal BLACK GIRL M/\G/C Volume 2 – Fall 2020 Salisbury University Offce of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity (OURCA) Enough Is Enough Eric Johnson Jr. (Featured on the Cover) ABSTRACT Racism has led to continuous confict between people since the beginning of time, and it is time for this evil to end – enough is enough. Since the beginning of 2020, we have lost many lives due to COVID-19 and police brutality as the whole world watched. Police brutality is the use of excessive force by an offcer, which can be legally defned as a civil rights violation. Over the years, we have lost many of our citizens and justice was not served. Eric Garner, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbrey … and so many more. The fact that I can fll at least two pages with victims is sickening – enough is enough! The brutality against African Americans this year has spiked to a recent all-time high. The videos of police killings have flled the news and internet – enough is enough. The death of George Floyd was heartbreaking. I personally couldn’t even fnish watching because the video was just so gruesome. All the lives that we have lost this year are heartbreaking – enough is enough. In this moment, the time we are in now, we do not need division. Instead, we need to come together in unity. The purpose of these photos is to show that enough is enough. I believe that one day we will all see the light at the end of this dark tunnel, but we have a long way still to go in order to come together. -

Harpercollins Books for the First-Year Student

S t u d e n t Featured Titles • American History and Society • Food, Health, and the Environment • World Issues • Memoir/World Views • Memoir/ American Voices • World Fiction • Fiction • Classic Fiction • Religion • Orientation Resources • Inspiration/Self-Help • Study Resources www.HarperAcademic.com Index View Print Exit Books for t H e f i r s t - Y e A r s t u d e n t • • 1 FEATURED TITLES The Boy Who Harnessed A Pearl In the Storm the Wind How i found My Heart in tHe Middle of tHe Ocean Creating Currents of eleCtriCity and Hope tori Murden McClure William kamkwamba & Bryan Mealer During June 1998, Tori Murden McClure set out to William Kamkwamba was born in Malawi, Africa, a row across the Atlantic Ocean by herself in a twenty- country plagued by AIDS and poverty. When, in three-foot plywood boat with no motor or sail. 2002, Malawi experienced their worst famine in 50 Within days she lost all communication with shore, years, fourteen-year-old William was forced to drop ultimately losing updates on the location of the Gulf out of school because his family could not afford the Stream and on the weather. In deep solitude and $80-a-year-tuition. However, he continued to think, perilous conditions, she was nonetheless learn, and dream. Armed with curiosity, determined to prove what one person with a mission determination, and a few old science textbooks he could do. When she was finally brought to her knees discovered in a nearby library, he embarked on a by a series of violent storms that nearly killed her, daring plan to build a windmill that could bring his she had to signal for help and go home in what felt family the electricity only two percent of Malawians like complete disgrace. -

Complete Catalog 7.6 MB

NEW WORLD LIBRARY WINTER–SPRING 2021 H J KRAMER ECKHART TOLLE EDITIONS NATARAJ PUBLISHING NAMASTE PUBLISHING Contents New Titles Primitive Mythology 2 Joseph Campbell 30 Three Simple Lines 3 Animals 32 Sacred Hags Oracle 4 Business & Prosperity 38 Pause. Breathe. Choose. 5 Celtic Studies 41 Be You, Only Better 6 Children’s 42 Becoming an Empowered Empath 7 Current Affairs / Social Change 43 Being Better 8 Eastern Philosophy 44 Go Big Now 9 Gift 48 Write a Poem, Save Your Life 10 Health & Wellness 49 The Full Spirit Workout 11 Literature, Writing & Creativity 55 Asking for a Pregnant Friend 12 Native American 60 Beyond Medicine 13 Parenting 61 Healing with Nature 14 Personal Growth 63 Permission Granted 15 Psychology & Philosophy 84 Oriental Mythology 16 Religion 88 Integrated Dog Training 17 Spanish Language 90 Women’s Interest 92 Backlist Audio 94 Bestsellers 18 Recently Published Titles 20 About New World Library 96 Eckhart Tolle 24 Academic Examination and Desk Copies 96 Shakti Gawain 26 Order Form 97 Dan Millman 28 Distribution and Contact Information 98 Primitive Mythology The Masks of God, Volume 1 Joseph Campbell Praise for The Masks of God: “The most comprehensive and the most imaginative treatment we have of a subject that sooner or later must claim every serious reader’s attention.” [ — New York Times ] • The first volume in Campbell’s monumental four-volume Masks of God series, originally published in 1959 by Viking and now revised with up-to-date science • Replaces the Penguin paperback edition of Primitive Mythology, which has sold over 215,000 copies since 1991 • The Masks of God titles have sold over 850,000 copies since 1991 and millions more since their original publication in the AVAILABLE IN DECEMBER late 1950s and early 1960s Mythology • $29.95 • Hardcover • This new hardcover Collected Works of Joseph Campbell 528 pp. -

Download Issue

'i: 911 i" Virtual History An Intimate ALTERNATIVESAND COUNTERFACTUALS History of Killing EDITZBBY NIALL FERGUSON FACETO FACEKILLING IN 2OTHCENTURY WARFARE JOANNA BOORKE I~~~Bc~-:~i::: i::::;:: i:: i:: : - ;- :: : : - ;:i --- I'---a~E_ ~~:History des9~~1- I~by~eYeryhist0rian..,:!' team of historians~~ ~~fO'c~· venre asenes a~ "' IIIJLIIUIUe~~,mi*l·nlnml ce~ury:turningpeints.8 ~un~. -a·--PC~~n~·:nn~,,,l, : nsih, Tnlnnmnb ~~"l":"LUR""I:nl'uI rlr, Y,,, lli1~61L1~11 a or:nusslas:war - Duel The Sword and ALEXANDERHAMILTON, AARON BURR the Shield ANDTHE FUTUREOF AMERICA THE MITROKHINARCHIVE AND THOMASFLEMING THESECRET HISTORY OFTHE KGB CHRISTOPHER ANDREW AND VASILI MITROKHIN THOMAS FLEMINGI :::·j~:-~~ ---··-·-- ····-: ···~: ···~~-·I ~~~:·-·~·-· I c ~"~'` "e~ ,revea~lnD· andrelevant...it remindf~ men:~power;and P~~~ ~~Sed humanrl,;,:,~~~ --~~~~~mTade~lPilitrakhin·the KGB:asu,- ~P[aCe-I'~KennethT.Jacksonl·IU··`l:l~~ _ ~rjppe~~~ i~ Histbry:andSocial Sciencesl -I:~,=_S--L~lhP~~~k Review :=i:::- -VYIUI"U'PUIIIIIIIIV a ~A~IONA~BES~'ELLER~-~ 5~1n,ll ~a~p~~f~~ 1 I g ~ I a;~ ss1CI1I Igs 8 Some~p~o~l~ithink :Mexico City was the ii0ngestj Mmp!:)lI,ever,:'made.l BUtJ Ust i: gett ing Ithe~:~as toug her. As a kid, I Was~in:~::gang.·. in trouble With:the:law. ifnot ior a c~i:id~n·5:c0~iud9k Who saw more in:me:'-'who knew that when kids are supported by caring adults, they can learn from their mistakes - I could have landed in prison. He sent me to an alternative school where people helped me get on track. k The children's court gave me the chance to land on:my feet. -

SBA Chief of Staff to Speak at New ABA Session at BEA Session at BEA

May 07, 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS: SBA Chief of Staff to Speak at New ABA • SBA Chief of Staff to Speak at New ABA Session at BEA Session at BEA ................................................ 1 May 07, 2009 -- Ana M. Ma, chief of staff at the U.S. Small • ABA Annual Meeting to Include Vote to Amend Business Administration, will be one of the featured speakers at a Bylaws .............................................................. 2 new ABA session at BookExpo America, "How SBA and the Federal Stimulus Package Can Help Your Business," to be held • IndieBound on the Rise! ................................... 3 Saturday, May 30, from 10:30 a.m. - noon, at the Javits Convention • Wine Guru Gary Vaynerchuk to Lead Social Center. Media Session at BEA ...................................... 3 "Ms. Ma is looking forward to talking with the members of the • ABA Announces Details of New CEO Contract American Booksellers Association," said SBA spokesman Jonathan .......................................................................... 3 Swain. "Ms. Ma will share what the SBA is doing as part of the • Trade Associations Call on Minnesota Recovery Act to help small businesses get access to much-needed Governor to Support E-Fairness Bill ................. 3 capital in these tough economic times, and how SBA is working to be a real partner with small businesses across the country in • North Carolina Latest State to Introduce creating jobs and driving our nation's economic recovery." Internet Sales Tax Provision ............................ 5 "We're delighted to have someone as knowledgeable about small • ABACUS Survey Works to Increase business issues as Ana Ma speak at this very important educational Participation: How Bookstores Benefit ............. 5 session," said ABA COO Oren Teicher, who will serve as • BTW Talks With New AAP Head Tom Allen ... -

Download Issue

I Sj~a a m v, -i 3 a 5 8 E1Zi: J· :I I~ ncD 09 O " ~g 3 3 n, 8 dr, -i--IPP~"~s 2 * " ~5~-rg .o~,·~ , qy ~ c ~ZnS a 3 I'3 ~j~5~f~ n ;r; W x -~E -·w ~· r~· I 3 v, 3 x o 3 ~:~Ye:i ·C de 5~;O~ h'l ::: ~oH iS~S~ ~V13 ~D n:i:::i:·z: ~V ~ j~ E· P,k< C) I ~ M oa ·i~" (D O n, t ~D e ~~ "s ~-aa s K "3 ;j' -- a Z K = C- -~· -- ~e ~ f S i- n~ ~i p~i r : F f t\ c ;j =: =- rr a x c; G 6 1: =j Ir~ =·o- ~ ~ - u- a I: W c; = r; b rv- 77~ = r; c. = C~C~ i= c. WQ WQAUTUMN 2002 THE WILSON QUARTERLY Published by the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars WQ website: Wilsonquarterly.com 12 LOCKWOOD IN ’84 by Jill Norgren Belva Lockwood’s campaign for the presidency in 1884 may have been quixotic, but it was historic, too, and as spirited and principled as the candidate herself. 22 LAST WORDS OF WILLIAM GADDIS by Paul Maliszewski Gaddis was a great American novelist, who failed to attract a great American audience. Perhaps that’s to his credit. 31 GERMANY ADRIFT Martin Walker • Steven Bach • John Hooper Little more than a decade after reunification, Germans are feeling the sting of truth in the old saying that the real problems begin when you finally get what you’ve always wanted. -

Anthropology Anthropology 2012

New Books & Selected Backlist | 2012 Anthropology Anthropology 2012 Contents New books and selected backlist Cultural On our website you’ll find much more than we can Anthropology 1 include in this catalog: a complete list of our books in Religion & Anthropology, sample chapters, tables of contents, and Culture 9 many other features, including ebook availability. Global Anthropology 13 Ordering information Asia 14 Order online at www.ucpress.edu/go/anthropology Forthcoming in 2012 16 To receive a 20% discount, enter source code 12M5196 into the shopping cart. Archaeology & Biological Discount only available on books shipped to North America, Anthropology 17 South America, Australia, and New Zealand UC Publishing For international orders, email [email protected] Services 18 For our desk and exam copy policy or to request a desk copy, Books for the visit www.ucpress.edu/go/instructors Classroom 19 Text Adoption Information 19 Join our email list Journals 20 It’s a fast and convenient way to be alerted about new and bestselling books and special discount offers. Author Index 21 Sign up today at www.ucpress.edu/subscribe Join UC Press As a nonprofit organization, UC Press relies on the generosity of the philanthropic community. To learn about giving levels and membership benefits, including special author events and book discounts, visit www.ucpress.edu. Or call our Director of Development at 510-643-8465. Cover art is from The Paper Road by Erik Mueggler. See facing page. Art at left is from Coffee Life in Japan by Merry White. See page 15. Cultural Anthropology Anthropology 2012 The Paper Road Archive and Experience in the Botanical Exploration of West China and Tibet Erik Mueggler This book interweaves the stories of two early twentieth-cen- tury botanists to explore the collaborative relationships each formed with Yunnan villagers in gathering botanical speci- mens from the borderlands between China, Tibet, and Burma. -

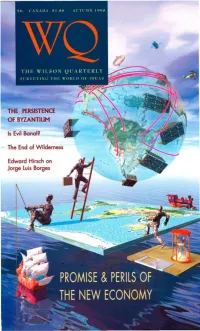

THE PERSISTENCE of Bylantium

.THE PERSISTENCE OF BYlANTIUM Is Evil Banal? The End of Wilderness Edward Hirsch on lorge luis Barges EDITOR’S COMMENT s the WQ goes to press, Wall Street is riding a roller coaster, alarmed by anxious talk of “global economic contagion” and wor- A ries about the prospects of U.S. companies. The economies of Japan, Russia, and Indonesia are only at the forefront of those teetering on the edge of disaster. Amid such alarms, this issue’s focus on the promise (and per- ils) of the emerging digital economy couldn’t be more timely. Consider, for example, the fact that the global network of telecommunica- tion-linked computers is already a big force, possibly the biggest, behind the rise of our interconnected global economy. Not only do networked technolo- gies make new kinds of commerce across borders and oceans possible; these technologies, and the content they carry, are increasingly the object of such commerce. As the digital economy goes, to a large extent, so goes the global economy. Consider, too, how networked technologies helped precipitate the turmoil. By linking national economies with others, the cybermarket has increasingly forced all players to play by common, or at least similar, rules—to some nations’ dismay and disadvantage. Customs, institutions, and practices that might have served their nations adequately in the relatively insular past— Japan’s elaborate protectionism, for example, or Indonesia’s crony capitalism— appear to be dysfunctional in today’s interconnected economy. Yet even where the problems are obvious, many national leaders are reluctant or unable to jet- tison traditional ways of doing business. -

Opening Doors INSIDE RICE SALLYPORT • the MAGAZINE of RICE UNIVERSITY • FALL 2004

The Magazine of Rice. University Opening Doors INSIDE RICE SALLYPORT • THE MAGAZINE OF RICE UNIVERSITY • FALL 2004 2 President's Message • 3 Returned Addressed Departments 5 Through the Sallyport • 14 Students • 38 Arts 40 On the Bookshelf • 42 Who's Who • 47 Scoreboard The new Boniuk 12 An enormous pool of 7 Center for the Study methane gas lies just and Advancement of beneath the ocean floor. Religious Tolerance Until now,scientists looks to establish a code thought that it had little ofreligious conduct. effect on the carbon cyde, 9 Fruit flies fly high aboard but they may be wrong. the International Space How do you encourage Station to help scientists 1 high-school students better understand to make the grade in genetic changes that science? A new training may occur in low-gravity program developed at environments. win The stars belong to everyone, but Rice helps students take ‘41F planetarium shows are available ownership ofscientific only to those who live near a concepts and principles. planetarium. That may change with a portable dome theater system developed at Rice. Do surveys alter the 11 perceptions ofthose who take them? Rice research suggests that surveys can subtly bias survey takers. And you thought A digitization project mayonnaise was just 5 in conjunction with the for sandwiches: Rice Shoah Foundation's researchers discover Visual History Archive unusual attractive will aid researchers and properties ofcertain educators in overcoming emulsions,including prejudice, intolerance, mayonnaise, that are and bigotry. similar to properties of Kevlar. 18 A Conversation with 28 Opening Doors David W. Leebron and Y. -

FORGING BONDS ACROSS BORDERS Transatlantic Collaborations for Women’S Rights and Social Justice in the Long Nineteenth Century

Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Supplement 13 (2017) FORGING BONDS ACROSS BORDERS Transatlantic Collaborations for Women’s Rights and Social Justice in the Long Nineteenth Century Edited by Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson and Anja Schüler Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Washington DC Editor: Richard F. Wetzell Supplement 13 Supplement Editor: Patricia C. Sutcliffe The Bulletin appears twice and the Supplement once a year; all are available free of charge. Current and back issues are available online at: www.ghi-dc.org/bulletin To sign up for a subscription or to report an address change, please contact Ms. Susanne Fabricius at [email protected]. For editorial comments or inquiries, please contact the editor at [email protected] or at the address below. For further information about the GHI, please visit our website www.ghi-dc.org. For general inquiries, please send an e-mail to [email protected]. German Historical Institute 1607 New Hampshire Ave NW Washington DC 20009-2562 Phone: (202) 387-3355 Fax: (202) 483-3430 © German Historical Institute 2017 All rights reserved ISSN 1048-9134 Cover: Offi cial board of the International Council of Women, 1899-1904; posed behind table at the Beethoven Saal, Berlin, June 8, 1904: Helene Lange, treasurer, Camille Vidart, recording secretary, Teresa Wilson, corresponding secretary, Lady Aberdeen, vice president, May Sewall, president, & Susan B. Anthony. Library of Congress P&P, LC-USZ62-44929. Photo by August Scherl. Bulletin of the German Historical Institute Supplement 13 | 2017 Forging Bonds Across Borders: Transatlantic Collaborations for Women’s Rights and Social Justice in the Long Nineteenth Century 5 INTRODUCTION Britta Waldschmidt-Nelson and Anja Schüler NEW WOMEN’S BIOGRAPHY 17 Transatlantic Freethinker, Feminist, and Pacifi st: Ernestine Rose in the 1870s Bonnie S. -

Download Issue

"The Reader's Catalog is the best book without a plot." --Newsweek "The most attractively laid out and compactlyinformative guide that I know of to books that are currently in print." -TheNew York ~imes "A catalog of 40,000 distinguished titles, organized in208 categories, forreaders who hunger "The catalog is forthe quality and variety available in discriminating yet expansive, today'smass-market bookstores. a feat of editingthat anyonewho has wast- Hallelyjah!"--~ime ed time rooting out data in the weeds of the Internet will appreciate." --Newsday "A browser's paradise." ---LibraryJournal "Avaluable literary tool that's "The scope of the endeavor notonly a reader'sresource, but also a is, as the kids are wont to browser:sdeligl~t." -Parade Magazine Say, awesome." --712eBaltimore Sun "Ihe best reading-group "lt must be called a and bookstore guide trumph." available." --I~he Los Angeles ~imes ~e Out ~lj!ir Gult)E~TH~~t~o~a~~B~oK~1-~ ~~~~ -II:I :: I ii 1111~ To ORDER:CALL 1-800-733-BOOK OR VISIT YOUR LOCAL BOOKSTORE TODAY 534·95 ' Distributed by Consortium "TheWorld & I is the greatest magazine ever. I read it cover to cover." FredTurek, Great Falls, Va. Try it ]FREE! NoRisk... No Cost... ~ToObligation! I~HEY~ EACH MONTH ~Ni~i,RL~2~i THE WORLD di I T~h~i~agazineforSerious Re" _,~,naive textl have ever seen OFFERS: .'~heMiorld E~Ipublishes themost compl··---- . betterperiodical· ina~y66years on thisp~,~tNo~nepub~"h~S toolfor me ~amesKrasowski~8v~falo,N.Y.IYsalearning CuRRar DearpotentialSubscriber: continuingtoleam? - a readerWho enjoys -

Copyright by Rebecca Anne D'orsogna 2013

Copyright by Rebecca Anne D’Orsogna 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Rebecca Anne D’Orsogna Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Yoga in America: History, Community Formation, and Consumerism Committee: Janet M. Davis, Supervisor Robert H. Abzug Carolyn Eastman Nhi T. Lieu Julia Mickenberg Yoga in America: History, Community Formation, and Consumerism by Rebecca Anne D’Orsogna, A.B.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication For Pete and Charlotte Yoga in America: History, Community Formation, and Consumerism Rebecca Anne D’Orsogna, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2013 Supervisor: Janet M. Davis This dissertation explores the ways in which various Western yoga teachers have interpreted and presented yoga to an American audience, and how media outlets have represented those yoga practices to a broader American audience between the 1890s and the 2010s. In particular, the case studies illuminate the ways in which contemporary concerns have influenced how yoga teachers and media reports have framed and responded to yoga practices. In this dissertation, I present a series of Western yoga practitioners that embody the most interesting and distinctive representations of popular understanding of yoga for their individual historical moments. Though the chapters do not reflect a linear development, recurrent discourses concerning Orientalism, post- colonialism, race, gender, sexuality, and class in the United States re-emerge in each chapter as different yoga schools respond to local and global concerns.