Hominid Adaptations and Extinctions Reviewed by MONTE L. Mccrossin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sergio Almécija

Sergio Almécija Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology Email: [email protected] Department of Anthropology Cellphone: (646) 943-1159 The George Washington University Science and Engineering Hall 800 22nd Street NW, Suite 6000 Washington, DC 20052 EDUCATION PhD, Cum Laude. Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and Universitat de Barcelona, Biological Anthropology, (October 30th, 2009). Dissertation: Evolution of the hand in Miocene apes: implications for the appearance of the human hand. Advisor: Salvador Moyà-Solà. MA with Advanced Studies Certificate (DEA). Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Biological Anthropology, 2007. BS. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Biological Sciences, 2005. PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor. Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology, Department of Anthropology, The George Washington University. Present. Research Instructor. Department of Anatomical Sciences, Stony Brook University. 2012-2015. Fulbright Postdoctoral Fellow. Department of Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History and New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology. 2010-2012. Research Associate. Department of Paleoprimatology and Human Paleontology, Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont. 2010-present. RESEARCH INTERESTS Evolution of humans and apes. Based on the morphology of living and fossil hominoids (and other primates), to identify key skeletal adaptations defining different stages of great ape and human evolution, as well as the original selective pressures responsible for specific evolutionary transitions. Morphometrics. Apart from describing new great ape and hominin fossil materials, I am interested in broad comparative studies of key regions of the skeleton using state-of-the-art methods such as three-dimensional morphometrics and phylogenetically-informed comparative methods. -

A New Species of Mioeuoticus (Lorisiformes, Primates) from the Early Middle Miocene of Kenya

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 125(2), 59–65, 2017 A new species of Mioeuoticus (Lorisiformes, Primates) from the early Middle Miocene of Kenya Yutaka KUNIMATSU1*, Hiroshi TSUJIKAWA2, Masato NAKATSUKASA3, Daisuke SHIMIZU3, Naomichi OGIHARA4, Yasuhiro KIKUCHI5, Yoshihiko NAKANO6, Tomo TAKANO7, Naoki MORIMOTO3, Hidemi ISHIDA8 1Faculty of Business Administration, Ryukoku University, Kyoto 612-8577, Japan 2Department of Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medical Science and Welfare, Tohoku Bunka Gakuen University, Sendai 981-8551, Japan 3Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan 4Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Science and Technology, Keio University, Yokohama 223-8522, Japan 5Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, Saga 849-8501, Japan 6Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University, Suita 565-0871, Japan 7Japan Monkey Center, Inuyama 484-0081, Japan 8Professor Emeritus, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Received 24 November 2016; accepted 22 March 2017 Abstract We here describe a prosimian specimen discovered from the early Middle Miocene (~15 Ma) of Nachola, northern Kenya. It is a right maxilla that preserves P4–M3, and is assigned to a new species of the Miocene lorisid genus Mioeuoticus. Previously, Mioeuoticus was known from the Early Miocene of East Africa. The Nachola specimen is therefore the first discovery of this genus from the Middle Mi- ocene. The presence of a new lorisid species in the Nachola fauna indicates a forested paleoenvironment for this locality, consistent with previously known evidence including the abundance of large-bodied hominoid fossils (Nacholapithecus kerioi), the dominance of browsers among the herbivore fauna, and the presence of plenty of petrified wood. -

Human Evolution: a Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H

PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Human Evolution: A Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H. Smith HUMAN EVOLUTION: A PALEOANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE F.H. Smith Department of Anthropology, Loyola University Chicago, USA Keywords: Human evolution, Miocene apes, Sahelanthropus, australopithecines, Australopithecus afarensis, cladogenesis, robust australopithecines, early Homo, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Australopithecus africanus/Australopithecus garhi, mitochondrial DNA, homology, Neandertals, modern human origins, African Transitional Group. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reconstructing Biological History: The Relationship of Humans and Apes 3. The Human Fossil Record: Basal Hominins 4. The Earliest Definite Hominins: The Australopithecines 5. Early Australopithecines as Primitive Humans 6. The Australopithecine Radiation 7. Origin and Evolution of the Genus Homo 8. Explaining Early Hominin Evolution: Controversy and the Documentation- Explanation Controversy 9. Early Homo erectus in East Africa and the Initial Radiation of Homo 10. After Homo erectus: The Middle Range of the Evolution of the Genus Homo 11. Neandertals and Late Archaics from Africa and Asia: The Hominin World before Modernity 12. The Origin of Modern Humans 13. Closing Perspective Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS The basic course of human biological history is well represented by the existing fossil record, although there is considerable debate on the details of that history. This review details both what is firmly understood (first echelon issues) and what is contentious concerning humanSAMPLE evolution. Most of the coCHAPTERSntention actually concerns the details (second echelon issues) of human evolution rather than the fundamental issues. For example, both anatomical and molecular evidence on living (extant) hominoids (apes and humans) suggests the close relationship of African great apes and humans (hominins). That relationship is demonstrated by the existing hominoid fossil record, including that of early hominins. -

The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research

Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Edited by Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham Chapters written in honour of Professor Colin P Groves Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Taxonomic tapestries : the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research / Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham, editors. ISBN: 9781925022360 (paperback) 9781925022377 (ebook) Subjects: Biology--Classification. Biology--Philosophy. Human ecology--Research. Coexistence of species--Research. Evolution (Biology)--Research. Taxonomists. Other Creators/Contributors: Behie, Alison M., editor. Oxenham, Marc F., editor. Dewey Number: 578.012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph courtesy of Hajarimanitra Rambeloarivony Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Contributors . .vii List of Figures and Tables . ix PART I 1. The Groves effect: 50 years of influence on behaviour, evolution and conservation research . 3 Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham PART II 2 . Characterisation of the endemic Sulawesi Lenomys meyeri (Muridae, Murinae) and the description of a new species of Lenomys . 13 Guy G Musser 3 . Gibbons and hominoid ancestry . 51 Peter Andrews and Richard J Johnson 4 . -

Unravelling the Positional Behaviour of Fossil Hominoids: Morphofunctional and Structural Analysis of the Primate Hindlimb

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Doctorado en Biodiversitat Facultad de Ciènces Tesis doctoral Unravelling the positional behaviour of fossil hominoids: Morphofunctional and structural analysis of the primate hindlimb Marta Pina Miguel 2016 Memoria presentada por Marta Pina Miguel para optar al grado de Doctor por la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, programa de doctorado en Biodiversitat del Departamento de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia (Facultad de Ciències). Este trabajo ha sido dirigido por el Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont) y el Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez (The George Washington Univertisy). Director Co-director Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez A mis padres y hermana. Y a todas aquelas personas que un día decidieron perseguir un sueño Contents Acknowledgments [in Spanish] 13 Abstract 19 Resumen 21 Section I. Introduction 23 Hominoid positional behaviour The great apes of the Vallès-Penedès Basin: State-of-the-art Section II. Objectives 55 Section III. Material and Methods 59 Hindlimb fossil remains of the Vallès-Penedès hominoids Comparative sample Area of study: The Vallès-Penedès Basin Methodology: Generalities and principles Section IV. -

Title Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of The

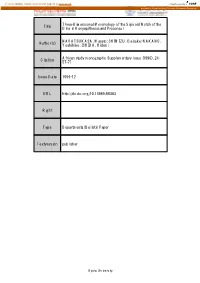

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Three-Dimensional Morphology of the Sigmoid Notch of the Title Ulna in Kenyapithecus and Proconsul NAKATSUKASA, Masato; SHIMIZU, Daisuke; NAKANO, Author(s) Yoshihiko; ISHIDA, Hidemi African study monographs. Supplementary issue (1996), 24: Citation 57-71 Issue Date 1996-12 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/68383 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, Suppl. 24: 57-71, December 1996 57 THREE-DIMENSIONAL MORPHOLOGY OF THE SIGMOID NOTCH OF THE ULNA IN KENYAPITHECUS AND PROCONSUL Masato Nakatsukasa Daisuke Shimizu Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University Yoshihiko Nakano Department of Biological Anthropology, Faculty of Human Sciences, Osaka University Hidemi Ishida Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Faculty of Science, Kyoto University ABSTRACT The three-dimensional (3-D) morphology of the sigmoid notch was examined in Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, and several living anthropoids by using an automatic 3-D digitizer. It was revealed that Kenyapithecus and Proconsul exhibit a very similar morphology of the dis tal region of the sigmoid notch; including the absence of a median keel and a downward sloped coronoid process. In addition, the proxilnal region of the sigmoid notch is curved more acutely relative to the distal region in Proconsul. This morphological complex is unique and not found in the examined living primates. The benefits of 3-D morphometries are discussed. Key Words: Kenyapithecus, Proconsul, sigmoid notch, three-dimensional morphometrics, ulna. INTRODUCTION Recently, automatic three-dimensional (3-0) digitizers have become more fre quently to be used for biometrics. -

Chapter 1 - Introduction

EURASIAN MIDDLE AND LATE MIOCENE HOMINOID PALEOBIOGEOGRAPHY AND THE GEOGRAPHIC ORIGINS OF THE HOMININAE by Mariam C. Nargolwalla A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by M. Nargolwalla (2009) Eurasian Middle and Late Miocene Hominoid Paleobiogeography and the Geographic Origins of the Homininae Mariam C. Nargolwalla Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology University of Toronto 2009 Abstract The origin and diversification of great apes and humans is among the most researched and debated series of events in the evolutionary history of the Primates. A fundamental part of understanding these events involves reconstructing paleoenvironmental and paleogeographic patterns in the Eurasian Miocene; a time period and geographic expanse rich in evidence of lineage origins and dispersals of numerous mammalian lineages, including apes. Traditionally, the geographic origin of the African ape and human lineage is considered to have occurred in Africa, however, an alternative hypothesis favouring a Eurasian origin has been proposed. This hypothesis suggests that that after an initial dispersal from Africa to Eurasia at ~17Ma and subsequent radiation from Spain to China, fossil apes disperse back to Africa at least once and found the African ape and human lineage in the late Miocene. The purpose of this study is to test the Eurasian origin hypothesis through the analysis of spatial and temporal patterns of distribution, in situ evolution, interprovincial and intercontinental dispersals of Eurasian terrestrial mammals in response to environmental factors. Using the NOW and Paleobiology databases, together with data collected through survey and excavation of middle and late Miocene vertebrate localities in Hungary and Romania, taphonomic bias and sampling completeness of Eurasian faunas are assessed. -

Full Issue 114

South African Journal of Science volume 114 number 5/6 Decolonising engineering in South Africa The Grootfontein aquifer: Governance of a hydro-social system Household food waste disposal in South Africa South African behavioural ecology research in a global perspective Volume 114 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Number 5/6 John Butler-Adam Academy of Science of South Africa May/June 2018 MANAGING EDITOR Linda Fick Academy of Science of South Africa South African ONLINE PUBLISHING Journal of Science SYSTEMS ADMINISTRATOR Nadine Wubbeling Academy of Science of South Africa ONLINE PUBLISHING ADMINISTRATOR Sbonga Dlamini eISSN: 1996-7489 Academy of Science of South Africa ASSOCIATE EDITORS Nicolas Beukes Leader Department of Geology, University of Johannesburg The Fourth Industrial Revolution and education John Butler-Adam .................................................................................................................... 1 Chris Chimimba Department of Zoology and Entomology, University of Pretoria Book Review Towards human development friendly universities Linda Chisholm Merridy Wilson-Strydom .......................................................................................................... 2 Centre for Education Rights and Transformation, University of A new look at Old Fourlegs Johannesburg Brian W. van Wilgen ................................................................................................................. 4 Teresa Coutinho Department of Microbiology and Commentary Plant Pathology, University of Pretoria Decolonising -

Alternative Models for Evaluating Variation and Sexual Dimorphism in Fossil Hominoid Samples Jeremiah E

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 140:253–264 (2009) Beyond Gorilla and Pongo: Alternative Models for Evaluating Variation and Sexual Dimorphism in Fossil Hominoid Samples Jeremiah E. Scott,1* Caitlin M. Schrein,1 and Jay Kelley2 1School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Institute of Human Origins, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-4101 2Department of Oral Biology, College of Dentistry, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60612 KEY WORDS bootstrap; dental variation; Lufengpithecus; Ouranopithecus; Sivapithecus ABSTRACT Sexual size dimorphism in the postca- cies. Using these samples, we also evaluated molar dimor- nine dentition of the late Miocene hominoid Lufengpithe- phism and taxonomic composition in two other Miocene cus lufengensis exceeds that in Pongo pygmaeus, demon- ape samples—Ouranopithecus macedoniensis from strating that the maximum degree of molar size dimor- Greece, specimens of which can be sexed based on associ- phism in apes is not represented among the extant ated canines and P3s, and the Sivapithecus sample from Hominoidea. It has not been established, however, that Haritalyangar, India. Ouranopithecus is more dimorphic the molars of Pongo are more dimorphic than those of than the extant taxa but is similar to Lufengpithecus, any other living primate. In this study, we used resam- demonstrating that the level of molar dimorphism pling-based methods to compare molar dimorphism in required for the Greek fossil sample under the single-spe- Gorilla, Pongo,andLufengpithecus to that in the papio- cies taxonomy is not unprecedented when the compara- nin Mandrillus leucophaeus to test two hypotheses: tive framework is expanded to include extinct primates. (1) Pongo possesses the most size-dimorphic molars In contrast, the Haritalyangar Sivapithecus sample, if among living primates and (2) molar size dimorphism in it represents a single species, exhibits substantially Lufengpithecus is greater than that in the most dimorphic greater molar dimorphism than does Lufengpithecus. -

Glaciation (Oakley, 1950). Variations in the Proposed Beginning Dates

EVOLUTION OF THE HUMAN HAND AMD THE GREAT HAND-AXE TRADITION Grover S. Krantz The hand-axe is both the earliest and the longest persisting of standar- dized stone tools. They present a continuous history of one tool type from the first to the third interglacial periods, a span.of at least 200,000 years and perhaps as many as half a million. Equally remarkable is their geographical range which covers all of Africa, western Europe and southern Asia--fully half of-the then habitable Old Vorld. Aside from differences in the local stone that was utilized, hand-axes from this whole area are constructed on the same plan and show no clear regional typology. Other tool types occur with hand-axes: utilized flakes are found at all levels, and in the later half of the sequence there-are cleavers, ovates, trimmed flakes and spherical stone balls. Throughout the sequence, however, the basic design of the hand-axe continues with its intended formnapparently unchanged. We thus have a continuous record of man's attempts to produce a single type of 'implement over mst of his tool making history. (See Figure 1.) Recent discoveries of fossil man have made it increasingly evident that biological evolution of the human body was also in progress coincident with the development of ancient stone tool types. 'While the exact time of appearance of Homo siens is still in some dispute (see Stewart, 1950 and Oakley., 1957), it is no nowseriously maintained that the earliest tool makers necessarily approximated the modern or even the neanderthal morphologies. -

A Unique Middle Miocene European Hominoid and the Origins of the Great Ape and Human Clade Salvador Moya` -Sola` A,1, David M

A unique Middle Miocene European hominoid and the origins of the great ape and human clade Salvador Moya` -Sola` a,1, David M. Albab,c, Sergio Alme´ cijac, Isaac Casanovas-Vilarc, Meike Ko¨ hlera, Soledad De Esteban-Trivignoc, Josep M. Roblesc,d, Jordi Galindoc, and Josep Fortunyc aInstitucio´Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avanc¸ats at Institut Catala`de Paleontologia (ICP) and Unitat d’Antropologia Biolo`gica (Dipartimento de Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal, i Ecologia), Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; bDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita`degli Studi di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121 Florence, Italy; cInstitut Catala`de Paleontologia, Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; and dFOSSILIA Serveis Paleontolo`gics i Geolo`gics, S.L. c/ Jaume I nu´m 87, 1er 5a, 08470 Sant Celoni, Barcelona, Spain Edited by David Pilbeam, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved March 4, 2009 (received for review November 20, 2008) The great ape and human clade (Primates: Hominidae) currently sediments by the diggers and bulldozers. After 6 years of includes orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans. fieldwork, 150 fossiliferous localities have been sampled from the When, where, and from which taxon hominids evolved are among 300-m-thick local stratigraphic series of ACM, which spans an the most exciting questions yet to be resolved. Within the Afro- interval of 1 million years (Ϸ12.5–11.3 Ma, Late Aragonian, pithecidae, the Kenyapithecinae (Kenyapithecini ؉ Equatorini) Middle Miocene). -

West African Chimpanzees

Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan West African Chimpanzees Compiled and edited by Rebecca Kormos, Christophe Boesch, Mohamed I. Bakarr and Thomas M. Butynski IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group IUCN The World Conservation Union Donors to the SSC Conservation Communications Programme and West African Chimpanzees Action Plan The IUCN Species Survival Commission is committed to communicating important species conservation information to natural resource managers, decision makers and others whose actions affect the conservation of biodiversity. The SSC’s Action Plans, Occasional Papers, newsletter Species and other publications are supported by a wide variety of generous donors including: The Sultanate of Oman established the Peter Scott IUCN/SSC Action Plan Fund in 1990. The Fund supports Action Plan development and implementation. To date, more than 80 grants have been made from the Fund to SSC Specialist Groups. The SSC is grateful to the Sultanate of Oman for its confidence in and support for species conservation worldwide. The Council of Agriculture (COA), Taiwan has awarded major grants to the SSC’s Wildlife Trade Programme and Conser- vation Communications Programme. This support has enabled SSC to continue its valuable technical advisory service to the Parties to CITES as well as to the larger global conservation community. Among other responsibilities, the COA is in charge of matters concerning the designation and management of nature reserves, conservation of wildlife and their habitats, conser- vation of natural landscapes, coordination of law enforcement efforts, as well as promotion of conservation education, research, and international cooperation. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) provides significant annual operating support to the SSC.