Reassessment of the Phylogenetic Relationships of the Late Miocene Apes Hispanopithecus and Rudapithecus Based on Vestibular Morphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sergio Almécija

Sergio Almécija Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology Email: [email protected] Department of Anthropology Cellphone: (646) 943-1159 The George Washington University Science and Engineering Hall 800 22nd Street NW, Suite 6000 Washington, DC 20052 EDUCATION PhD, Cum Laude. Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and Universitat de Barcelona, Biological Anthropology, (October 30th, 2009). Dissertation: Evolution of the hand in Miocene apes: implications for the appearance of the human hand. Advisor: Salvador Moyà-Solà. MA with Advanced Studies Certificate (DEA). Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Biological Anthropology, 2007. BS. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Biological Sciences, 2005. PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor. Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology, Department of Anthropology, The George Washington University. Present. Research Instructor. Department of Anatomical Sciences, Stony Brook University. 2012-2015. Fulbright Postdoctoral Fellow. Department of Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History and New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology. 2010-2012. Research Associate. Department of Paleoprimatology and Human Paleontology, Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont. 2010-present. RESEARCH INTERESTS Evolution of humans and apes. Based on the morphology of living and fossil hominoids (and other primates), to identify key skeletal adaptations defining different stages of great ape and human evolution, as well as the original selective pressures responsible for specific evolutionary transitions. Morphometrics. Apart from describing new great ape and hominin fossil materials, I am interested in broad comparative studies of key regions of the skeleton using state-of-the-art methods such as three-dimensional morphometrics and phylogenetically-informed comparative methods. -

A New Species of Mioeuoticus (Lorisiformes, Primates) from the Early Middle Miocene of Kenya

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 125(2), 59–65, 2017 A new species of Mioeuoticus (Lorisiformes, Primates) from the early Middle Miocene of Kenya Yutaka KUNIMATSU1*, Hiroshi TSUJIKAWA2, Masato NAKATSUKASA3, Daisuke SHIMIZU3, Naomichi OGIHARA4, Yasuhiro KIKUCHI5, Yoshihiko NAKANO6, Tomo TAKANO7, Naoki MORIMOTO3, Hidemi ISHIDA8 1Faculty of Business Administration, Ryukoku University, Kyoto 612-8577, Japan 2Department of Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medical Science and Welfare, Tohoku Bunka Gakuen University, Sendai 981-8551, Japan 3Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan 4Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Science and Technology, Keio University, Yokohama 223-8522, Japan 5Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, Saga 849-8501, Japan 6Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University, Suita 565-0871, Japan 7Japan Monkey Center, Inuyama 484-0081, Japan 8Professor Emeritus, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Received 24 November 2016; accepted 22 March 2017 Abstract We here describe a prosimian specimen discovered from the early Middle Miocene (~15 Ma) of Nachola, northern Kenya. It is a right maxilla that preserves P4–M3, and is assigned to a new species of the Miocene lorisid genus Mioeuoticus. Previously, Mioeuoticus was known from the Early Miocene of East Africa. The Nachola specimen is therefore the first discovery of this genus from the Middle Mi- ocene. The presence of a new lorisid species in the Nachola fauna indicates a forested paleoenvironment for this locality, consistent with previously known evidence including the abundance of large-bodied hominoid fossils (Nacholapithecus kerioi), the dominance of browsers among the herbivore fauna, and the presence of plenty of petrified wood. -

Download Full Article in PDF Format

Dryopithecins, Darwin, de Bonis, and the European origin of the African apes and human clade David R. BEGUN University of Toronto, Department of Anthropology, 19 Russell Street, Toronto, ON, M5S 2S2 (Canada) [email protected] Begun R. D. 2009. — Dryopithecins, Darwin, de Bonis, and the European origin of the African apes and human clade. Geodiversitas 31 (4) : 789-816. ABSTRACT Darwin famously opined that the most likely place of origin of the common ancestor of African apes and humans is Africa, given the distribution of its liv- ing descendents. But it is infrequently recalled that immediately afterwards, Darwin, in his typically thorough and cautious style, noted that a fossil ape from Europe, Dryopithecus, may instead represent the ancestors of African apes, which dispersed into Africa from Europe. Louis de Bonis and his collaborators were the fi rst researchers in the modern era to echo Darwin’s suggestion about apes from Europe. Resulting from their spectacular discoveries in Greece over several decades, de Bonis and colleagues have shown convincingly that African KEY WORDS ape and human clade members (hominines) lived in Europe at least 9.5 million Mammalia, years ago. Here I review the fossil record of hominoids in Europe as it relates to Primates, Dryopithecus, the origins of the hominines. While I diff er in some details with Louis, we are Hispanopithecus, in complete agreement on the importance of Europe in determining the fate Rudapithecus, of the African ape and human clade. Th ere is no doubt that Louis de Bonis is Ouranopithecus, hominine origins, a pioneer in advancing our understanding of this fascinating time in our evo- new subtribe. -

Human Evolution: a Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H

PHYSICAL (BIOLOGICAL) ANTHROPOLOGY - Human Evolution: A Paleoanthropological Perspective - F.H. Smith HUMAN EVOLUTION: A PALEOANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE F.H. Smith Department of Anthropology, Loyola University Chicago, USA Keywords: Human evolution, Miocene apes, Sahelanthropus, australopithecines, Australopithecus afarensis, cladogenesis, robust australopithecines, early Homo, Homo erectus, Homo heidelbergensis, Australopithecus africanus/Australopithecus garhi, mitochondrial DNA, homology, Neandertals, modern human origins, African Transitional Group. Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reconstructing Biological History: The Relationship of Humans and Apes 3. The Human Fossil Record: Basal Hominins 4. The Earliest Definite Hominins: The Australopithecines 5. Early Australopithecines as Primitive Humans 6. The Australopithecine Radiation 7. Origin and Evolution of the Genus Homo 8. Explaining Early Hominin Evolution: Controversy and the Documentation- Explanation Controversy 9. Early Homo erectus in East Africa and the Initial Radiation of Homo 10. After Homo erectus: The Middle Range of the Evolution of the Genus Homo 11. Neandertals and Late Archaics from Africa and Asia: The Hominin World before Modernity 12. The Origin of Modern Humans 13. Closing Perspective Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary UNESCO – EOLSS The basic course of human biological history is well represented by the existing fossil record, although there is considerable debate on the details of that history. This review details both what is firmly understood (first echelon issues) and what is contentious concerning humanSAMPLE evolution. Most of the coCHAPTERSntention actually concerns the details (second echelon issues) of human evolution rather than the fundamental issues. For example, both anatomical and molecular evidence on living (extant) hominoids (apes and humans) suggests the close relationship of African great apes and humans (hominins). That relationship is demonstrated by the existing hominoid fossil record, including that of early hominins. -

The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research

Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Edited by Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham Chapters written in honour of Professor Colin P Groves Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Taxonomic tapestries : the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research / Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham, editors. ISBN: 9781925022360 (paperback) 9781925022377 (ebook) Subjects: Biology--Classification. Biology--Philosophy. Human ecology--Research. Coexistence of species--Research. Evolution (Biology)--Research. Taxonomists. Other Creators/Contributors: Behie, Alison M., editor. Oxenham, Marc F., editor. Dewey Number: 578.012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph courtesy of Hajarimanitra Rambeloarivony Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Contributors . .vii List of Figures and Tables . ix PART I 1. The Groves effect: 50 years of influence on behaviour, evolution and conservation research . 3 Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham PART II 2 . Characterisation of the endemic Sulawesi Lenomys meyeri (Muridae, Murinae) and the description of a new species of Lenomys . 13 Guy G Musser 3 . Gibbons and hominoid ancestry . 51 Peter Andrews and Richard J Johnson 4 . -

Unravelling the Positional Behaviour of Fossil Hominoids: Morphofunctional and Structural Analysis of the Primate Hindlimb

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi queda condicionat a lʼacceptació de les condicions dʼús establertes per la següent llicència Creative Commons: http://cat.creativecommons.org/?page_id=184 ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis queda condicionado a la aceptación de las condiciones de uso establecidas por la siguiente licencia Creative Commons: http://es.creativecommons.org/blog/licencias/ WARNING. The access to the contents of this doctoral thesis it is limited to the acceptance of the use conditions set by the following Creative Commons license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/?lang=en Doctorado en Biodiversitat Facultad de Ciènces Tesis doctoral Unravelling the positional behaviour of fossil hominoids: Morphofunctional and structural analysis of the primate hindlimb Marta Pina Miguel 2016 Memoria presentada por Marta Pina Miguel para optar al grado de Doctor por la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, programa de doctorado en Biodiversitat del Departamento de Biologia Animal, de Biologia Vegetal i d’Ecologia (Facultad de Ciències). Este trabajo ha sido dirigido por el Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà (Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont) y el Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez (The George Washington Univertisy). Director Co-director Dr. Salvador Moyà Solà Dr. Sergio Almécija Martínez A mis padres y hermana. Y a todas aquelas personas que un día decidieron perseguir un sueño Contents Acknowledgments [in Spanish] 13 Abstract 19 Resumen 21 Section I. Introduction 23 Hominoid positional behaviour The great apes of the Vallès-Penedès Basin: State-of-the-art Section II. Objectives 55 Section III. Material and Methods 59 Hindlimb fossil remains of the Vallès-Penedès hominoids Comparative sample Area of study: The Vallès-Penedès Basin Methodology: Generalities and principles Section IV. -

Taxonomic Tapestries the Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research

Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Edited by Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham Chapters written in honour of Professor Colin P Groves Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Taxonomic tapestries : the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research / Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham, editors. ISBN: 9781925022360 (paperback) 9781925022377 (ebook) Subjects: Biology--Classification. Biology--Philosophy. Human ecology--Research. Coexistence of species--Research. Evolution (Biology)--Research. Taxonomists. Other Creators/Contributors: Behie, Alison M., editor. Oxenham, Marc F., editor. Dewey Number: 578.012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph courtesy of Hajarimanitra Rambeloarivony Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Contributors . .vii List of Figures and Tables . ix PART I 1. The Groves effect: 50 years of influence on behaviour, evolution and conservation research . 3 Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham PART II 2 . Characterisation of the endemic Sulawesi Lenomys meyeri (Muridae, Murinae) and the description of a new species of Lenomys . 13 Guy G Musser 3 . Gibbons and hominoid ancestry . 51 Peter Andrews and Richard J Johnson 4 . -

Evolution of Grasping Among Anthropoids

doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01582.x Evolution of grasping among anthropoids E. POUYDEBAT,* M. LAURIN, P. GORCE* & V. BELSà *Handibio, Universite´ du Sud Toulon-Var, La Garde, France Comparative Osteohistology, UMR CNRS 7179, Universite´ Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris 6), Paris, France àUMR 7179, MNHN, Paris, France Keywords: Abstract behaviour; The prevailing hypothesis about grasping in primates stipulates an evolution grasping; from power towards precision grips in hominids. The evolution of grasping is hominids; far more complex, as shown by analysis of new morphometric and behavio- palaeobiology; ural data. The latter concern the modes of food grasping in 11 species (one phylogeny; platyrrhine, nine catarrhines and humans). We show that precision grip and precision grip; thumb-lateral behaviours are linked to carpus and thumb length, whereas primates; power grasping is linked to second and third digit length. No phylogenetic variance partitioning with PVR. signal was found in the behavioural characters when using squared-change parsimony and phylogenetic eigenvector regression, but such a signal was found in morphometric characters. Our findings shed new light on previously proposed models of the evolution of grasping. Inference models suggest that Australopithecus, Oreopithecus and Proconsul used a precision grip. very old behaviour, as it occurs in anurans, crocodilians, Introduction squamates and several therian mammals (Gray, 1997; Grasping behaviour is a key activity in primates to obtain Iwaniuk & Whishaw, 2000). On the contrary, the food. The hand is used in numerous activities of manip- precision grip, in which an object is held between the ulation and locomotion and is linked to several func- distal surfaces of the thumb and the index finger, is tional adaptations (Godinot & Beard, 1993; Begun et al., usually viewed as a derived function, linked to tool use 1997; Godinot et al., 1997). -

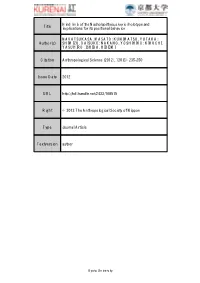

Title Hind Limb of the Nacholapithecus Kerioi Holotype And

Hind limb of the Nacholapithecus kerioi holotype and Title implications for its positional behavior NAKATSUKASA, MASATO; KUNIMATSU, YUTAKA; Author(s) SHIMIZU, DAISUKE; NAKANO, YOSHIHIKO; KIKUCHI, YASUHIRO; ISHIDA, HIDEMI Citation Anthropological Science (2012), 120(3): 235-250 Issue Date 2012 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/168515 Right © 2012 The Anthropological Society of Nippon Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University Hind limb of the Nacholapithecus kerioi holotype and implications for its positional behavior (revised) Masato Nakatsukasa, Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Yutaka Kunimatsu, Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Daisuke Shimizu, Japan Monkey Centre, Inuyama, Aichi 484-0081, Japan Yosihiko Nakano, Department of Biological Anthropology, Osaka University, Suita, Osaka 565-8502, Japan Yashihiro Kikuchi, Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, Saga 849-8501, Japan Hidemi Ishida, Department of Nursing, Seisen University, Hikone, Shiga 521-1123, Japan Running title: Nacholapithecus hind limb Corresponding author Masato Nakatsukasa, Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan [email protected] 1 Abstract We present the final description of the hind limb elements of the Nacholapithecus kerioi holotype (KNM-BG 35250) from the middle Miocene of Kenya. Previously, it has been noted that the postcranial (i.e., the phalanges, spine, and shoulder girdle) anatomy of N. kerioi shows greater affinity to other early/middle Miocene African hominoids, collectively called "non-specialized pronograde arboreal quadrupeds", than to extant hominoids. This was also the case for the hind limb. -

A Unique Middle Miocene European Hominoid and the Origins of the Great Ape and Human Clade Salvador Moya` -Sola` A,1, David M

A unique Middle Miocene European hominoid and the origins of the great ape and human clade Salvador Moya` -Sola` a,1, David M. Albab,c, Sergio Alme´ cijac, Isaac Casanovas-Vilarc, Meike Ko¨ hlera, Soledad De Esteban-Trivignoc, Josep M. Roblesc,d, Jordi Galindoc, and Josep Fortunyc aInstitucio´Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avanc¸ats at Institut Catala`de Paleontologia (ICP) and Unitat d’Antropologia Biolo`gica (Dipartimento de Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal, i Ecologia), Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; bDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita`degli Studi di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121 Florence, Italy; cInstitut Catala`de Paleontologia, Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; and dFOSSILIA Serveis Paleontolo`gics i Geolo`gics, S.L. c/ Jaume I nu´m 87, 1er 5a, 08470 Sant Celoni, Barcelona, Spain Edited by David Pilbeam, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved March 4, 2009 (received for review November 20, 2008) The great ape and human clade (Primates: Hominidae) currently sediments by the diggers and bulldozers. After 6 years of includes orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans. fieldwork, 150 fossiliferous localities have been sampled from the When, where, and from which taxon hominids evolved are among 300-m-thick local stratigraphic series of ACM, which spans an the most exciting questions yet to be resolved. Within the Afro- interval of 1 million years (Ϸ12.5–11.3 Ma, Late Aragonian, pithecidae, the Kenyapithecinae (Kenyapithecini ؉ Equatorini) Middle Miocene). -

Human Origins and Environmental Backgrounds Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects

HUMAN ORIGINS AND ENVIRONMENTAL BACKGROUNDS DEVELOPMENTS IN PRIMATOLOGY: PROGRESS AND PROSPECTS Series Editor: Russell H. Tuttle University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois This peer-reviewed book series will meld the facts of organic diversity with the conti- nuity of the evolutionary process. The volumes in this series will exemplify the diver- sity of theoretical perspectives and methodological approaches currently employed by primatologists and physical anthropologists. Specific coverage includes: primate behavior in natural habitats and captive settings; primate ecology and conservation; functional morphology and developmental biology of primates; primate systematics; genetic and phenotypic differences among living primates; and paleoprimatology. ALL APES GREAT AND SMALL VOLUME 1: AFRICAN APES Edited by Birute M. F. Galdikas, Nancy Erickson Briggs, Lori K. Sheeran, Gary L. Shapiro and Jane Goodall THE GUENONS: DIVERSITY AND ADAPTATION IN AFRICAN MONKEYS Edited by Mary E. Glenn and Marina Cords ANIMAL BODIES, HUMAN MINDS: APE, DOLPHIN, AND PARROT LANGUAGE SKILLS William A. Hillix and Duane M. Rumbaugh COMPARATIVE VERTEBRATE COGNITION: ARE PRIMATES SUPERIOR TO NON-PRIMATES Lesley J. Rogers and Gisela Kaplan ANTHROPOID ORIGINS: NEW VISIONS Callum F. Ross and Richard F. Kay MODERN MORPHOMETRICS IN PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Edited by Dennis E. Slice NURSERY REARING OF NON-HUMAN PRIMATES IN THE 21ST CENTURY Edited by Gene P. Sackett, Gerald Ruppenthal and Kate Elias BEHAVIORAL FLEXIBILITY IN PRIMATES: CAUSES AND CONSEQUENCES Clara B. Jones NEW -

A New Dryopithecine Mandibular Fragment from the Middle Miocene

Journal of Human Evolution 145 (2020) 102790 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Short Communications A new dryopithecine mandibular fragment from the middle Miocene of Abocador de Can Mata and the taxonomic status of ‘Sivapithecus’ occidentalis from Can Vila (Valles-Pened es Basin, NE Iberian Peninsula) * David M. Alba a, , Josep Fortuny a, Josep M. Robles a, Federico Bernardini b, c, Miriam Perez de los Ríos d, Claudio Tuniz c, b, e, Salvador Moya-Sol a a, f, g, * Clement Zanolli h, a Institut Catala de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Edifici ICTA-ICP, Carrer de les Columnes s/n, Campus de la UAB, Cerdanyola del Valles, Barcelona, 08193, Spain b Centro Fermi, Museo Storico della Fisica e Centro di Studi e Ricerche ‘Enrico Fermi’, Piazza del Viminale 1, Roma, 00184, Italy c Multidisciplinary Laboratory, The ‘Abdus Salam’ International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Via Beirut 31, Trieste, 34151, Italy d ~ Departamento de Antropología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de Chile, Ignacio Carrera Pinto, 1045, Nunoa,~ Santiago, Chile e Center for Archaeological Science, University of Wollongong, Northfields Ave, Wollongong, NSW, 2522, Australia f Unitat d'Antropologia Biologica, Department de Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal i Ecologia, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Campus de la UAB, Cerdanyola del Valles, Barcelona, Spain g Institucio Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (ICREA), Pg. Lluís Companys 23, Barcelona, 08010, Spain h Laboratoire PACEA, UMR 5199 CNRS, Universite de Bordeaux, allee Geoffroy Saint Hilaire, 33615 Pessac Cedex, France article info Article history: 2012; Alba et al., 2018).