Human Origins and Environmental Backgrounds Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sergio Almécija

Sergio Almécija Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology Email: [email protected] Department of Anthropology Cellphone: (646) 943-1159 The George Washington University Science and Engineering Hall 800 22nd Street NW, Suite 6000 Washington, DC 20052 EDUCATION PhD, Cum Laude. Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and Universitat de Barcelona, Biological Anthropology, (October 30th, 2009). Dissertation: Evolution of the hand in Miocene apes: implications for the appearance of the human hand. Advisor: Salvador Moyà-Solà. MA with Advanced Studies Certificate (DEA). Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont at Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Biological Anthropology, 2007. BS. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Biological Sciences, 2005. PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor. Center for the Advanced Study of Human Paleobiology, Department of Anthropology, The George Washington University. Present. Research Instructor. Department of Anatomical Sciences, Stony Brook University. 2012-2015. Fulbright Postdoctoral Fellow. Department of Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History and New York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology. 2010-2012. Research Associate. Department of Paleoprimatology and Human Paleontology, Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont. 2010-present. RESEARCH INTERESTS Evolution of humans and apes. Based on the morphology of living and fossil hominoids (and other primates), to identify key skeletal adaptations defining different stages of great ape and human evolution, as well as the original selective pressures responsible for specific evolutionary transitions. Morphometrics. Apart from describing new great ape and hominin fossil materials, I am interested in broad comparative studies of key regions of the skeleton using state-of-the-art methods such as three-dimensional morphometrics and phylogenetically-informed comparative methods. -

A New Species of Mioeuoticus (Lorisiformes, Primates) from the Early Middle Miocene of Kenya

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 125(2), 59–65, 2017 A new species of Mioeuoticus (Lorisiformes, Primates) from the early Middle Miocene of Kenya Yutaka KUNIMATSU1*, Hiroshi TSUJIKAWA2, Masato NAKATSUKASA3, Daisuke SHIMIZU3, Naomichi OGIHARA4, Yasuhiro KIKUCHI5, Yoshihiko NAKANO6, Tomo TAKANO7, Naoki MORIMOTO3, Hidemi ISHIDA8 1Faculty of Business Administration, Ryukoku University, Kyoto 612-8577, Japan 2Department of Rehabilitation, Faculty of Medical Science and Welfare, Tohoku Bunka Gakuen University, Sendai 981-8551, Japan 3Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan 4Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Science and Technology, Keio University, Yokohama 223-8522, Japan 5Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, Saga 849-8501, Japan 6Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University, Suita 565-0871, Japan 7Japan Monkey Center, Inuyama 484-0081, Japan 8Professor Emeritus, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Received 24 November 2016; accepted 22 March 2017 Abstract We here describe a prosimian specimen discovered from the early Middle Miocene (~15 Ma) of Nachola, northern Kenya. It is a right maxilla that preserves P4–M3, and is assigned to a new species of the Miocene lorisid genus Mioeuoticus. Previously, Mioeuoticus was known from the Early Miocene of East Africa. The Nachola specimen is therefore the first discovery of this genus from the Middle Mi- ocene. The presence of a new lorisid species in the Nachola fauna indicates a forested paleoenvironment for this locality, consistent with previously known evidence including the abundance of large-bodied hominoid fossils (Nacholapithecus kerioi), the dominance of browsers among the herbivore fauna, and the presence of plenty of petrified wood. -

The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research

Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Taxonomic Tapestries The Threads of Evolutionary, Behavioural and Conservation Research Edited by Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham Chapters written in honour of Professor Colin P Groves Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: Taxonomic tapestries : the threads of evolutionary, behavioural and conservation research / Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham, editors. ISBN: 9781925022360 (paperback) 9781925022377 (ebook) Subjects: Biology--Classification. Biology--Philosophy. Human ecology--Research. Coexistence of species--Research. Evolution (Biology)--Research. Taxonomists. Other Creators/Contributors: Behie, Alison M., editor. Oxenham, Marc F., editor. Dewey Number: 578.012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph courtesy of Hajarimanitra Rambeloarivony Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2015 ANU Press Contents List of Contributors . .vii List of Figures and Tables . ix PART I 1. The Groves effect: 50 years of influence on behaviour, evolution and conservation research . 3 Alison M Behie and Marc F Oxenham PART II 2 . Characterisation of the endemic Sulawesi Lenomys meyeri (Muridae, Murinae) and the description of a new species of Lenomys . 13 Guy G Musser 3 . Gibbons and hominoid ancestry . 51 Peter Andrews and Richard J Johnson 4 . -

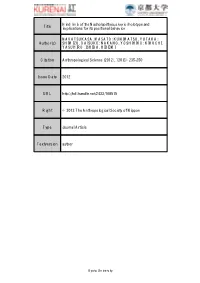

Title Hind Limb of the Nacholapithecus Kerioi Holotype And

Hind limb of the Nacholapithecus kerioi holotype and Title implications for its positional behavior NAKATSUKASA, MASATO; KUNIMATSU, YUTAKA; Author(s) SHIMIZU, DAISUKE; NAKANO, YOSHIHIKO; KIKUCHI, YASUHIRO; ISHIDA, HIDEMI Citation Anthropological Science (2012), 120(3): 235-250 Issue Date 2012 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/168515 Right © 2012 The Anthropological Society of Nippon Type Journal Article Textversion author Kyoto University Hind limb of the Nacholapithecus kerioi holotype and implications for its positional behavior (revised) Masato Nakatsukasa, Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Yutaka Kunimatsu, Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Daisuke Shimizu, Japan Monkey Centre, Inuyama, Aichi 484-0081, Japan Yosihiko Nakano, Department of Biological Anthropology, Osaka University, Suita, Osaka 565-8502, Japan Yashihiro Kikuchi, Department of Anatomy and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Saga University, Saga 849-8501, Japan Hidemi Ishida, Department of Nursing, Seisen University, Hikone, Shiga 521-1123, Japan Running title: Nacholapithecus hind limb Corresponding author Masato Nakatsukasa, Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan [email protected] 1 Abstract We present the final description of the hind limb elements of the Nacholapithecus kerioi holotype (KNM-BG 35250) from the middle Miocene of Kenya. Previously, it has been noted that the postcranial (i.e., the phalanges, spine, and shoulder girdle) anatomy of N. kerioi shows greater affinity to other early/middle Miocene African hominoids, collectively called "non-specialized pronograde arboreal quadrupeds", than to extant hominoids. This was also the case for the hind limb. -

Reassessment of the Phylogenetic Relationships of the Late Miocene Apes Hispanopithecus and Rudapithecus Based on Vestibular Morphology

Reassessment of the phylogenetic relationships of the late Miocene apes Hispanopithecus and Rudapithecus based on vestibular morphology Alessandro Urciuolia,1, Clément Zanollib, Sergio Almécijaa,c,d, Amélie Beaudeta,e,f,g, Jean Dumoncelh, Naoki Morimotoi, Masato Nakatsukasai, Salvador Moyà-Solàa,j,k, David R. Begunl, and David M. Albaa,1 aInstitut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Barcelona, Spain; bUniv. Bordeaux, CNRS, MCC, PACEA, UMR 5199, F-33600 Pessac, France; cDivision of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024; dNew York Consortium in Evolutionary Primatology, New York, NY 10016; eDepartment of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 1QH, United Kingdom; fSchool of Geography, Archaeology, and Environmental Studies, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, WITS 2050, South Africa; gDepartment of Anatomy, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0001, South Africa; hLaboratoire Anthropology and Image Synthesis, UMR 5288 CNRS, Université de Toulouse, 31073 Toulouse, France; iLaboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, 606 8502 Kyoto, Japan; jInstitució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats, 08010 Barcelona, Spain; kUnitat d’Antropologia, Departament de Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal i Ecologia, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, 08193 Barcelona, Spain; and lDepartment of Anthropology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 2S2, Canada Edited by Justin S. Sipla, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member C. O. Lovejoy December 3, 2020 (received for review July 19, 2020) Late Miocene great apes are key to reconstructing the ancestral Dryopithecus and allied forms have long been debated. Until a morphotype from which earliest hominins evolved. Despite con- decade ago, several species of European apes from the middle sensus that the late Miocene dryopith great apes Hispanopithecus and late Miocene were included within this genus (9–16). -

A Unique Middle Miocene European Hominoid and the Origins of the Great Ape and Human Clade Salvador Moya` -Sola` A,1, David M

A unique Middle Miocene European hominoid and the origins of the great ape and human clade Salvador Moya` -Sola` a,1, David M. Albab,c, Sergio Alme´ cijac, Isaac Casanovas-Vilarc, Meike Ko¨ hlera, Soledad De Esteban-Trivignoc, Josep M. Roblesc,d, Jordi Galindoc, and Josep Fortunyc aInstitucio´Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avanc¸ats at Institut Catala`de Paleontologia (ICP) and Unitat d’Antropologia Biolo`gica (Dipartimento de Biologia Animal, Biologia Vegetal, i Ecologia), Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; bDipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Universita`degli Studi di Firenze, Via G. La Pira 4, 50121 Florence, Italy; cInstitut Catala`de Paleontologia, Universitat Auto`noma de Barcelona, Edifici ICP, Campus de Bellaterra s/n, 08193 Cerdanyola del Valle`s, Barcelona, Spain; and dFOSSILIA Serveis Paleontolo`gics i Geolo`gics, S.L. c/ Jaume I nu´m 87, 1er 5a, 08470 Sant Celoni, Barcelona, Spain Edited by David Pilbeam, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved March 4, 2009 (received for review November 20, 2008) The great ape and human clade (Primates: Hominidae) currently sediments by the diggers and bulldozers. After 6 years of includes orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans. fieldwork, 150 fossiliferous localities have been sampled from the When, where, and from which taxon hominids evolved are among 300-m-thick local stratigraphic series of ACM, which spans an the most exciting questions yet to be resolved. Within the Afro- interval of 1 million years (Ϸ12.5–11.3 Ma, Late Aragonian, pithecidae, the Kenyapithecinae (Kenyapithecini ؉ Equatorini) Middle Miocene). -

Dental Anatomy of the Early Hominid, Orrorin Tugenensis, from the Lukeino Formation, Tugen Hills, Kenya

Revue de Paléobiologie, Genève (décembre 2018) 37 (2): 577-591 ISSN 0253-6730 Dental anatomy of the early hominid, Orrorin tugenensis, from the Lukeino Formation, Tugen Hills, Kenya Brigitte SENUT1,*, Martin PICKFORD2 & Dominique GOMMERY3 1 CR2P - Centre de Recherche en Paléontologie - Paris, MNHN - CNRS - Sorbonne Université, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, CP 38, 8, rue Buffon, F-75252 Paris cedex 05, France. E-mail: *[email protected] 2 CR2P - Centre de Recherche en Paléontologie - Paris, MNHN - CNRS - Sorbonne Université, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, CP 38, 8, rue Buffon, F-75252 Paris cedex 05, France. E-mail: [email protected] 3 CR2P - Centre de Recherche en Paléontologie - Paris, CNRS - MNHN - Sorbonne Université, Campus Pierre et Marie Curie - Jussieu, T. 46 - 56, E.5, Case 104, F-75252 Paris cedex 05, France. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Subsequent to the initial publication of the Late Miocene hominid genus and species, Orrorin tugenensis, in 2001, additional dental remains were discovered which comprise the subject of this paper. Detailed descriptions of all the Orrorin fossils are provided and comparisons are made with other late Miocene and early Pliocene hominoid fossils, in particular Ardipithecus ramidus, Ardipithecus kadabba and Sahelanthropus tchadensis. The Late Miocene Lukeino Formation from which the remains of Orrorin were collected, has yielded rare remains of a chimpanzee-like hominoid as well as a gorilla-sized ape. Although comparisons with Ardipithecus ramidus are difficult due to the fact that measurements of the teeth have not been published, it is concluded thatAr. ramidus is chimpanzee-like in several features, whereas some of the Ardipithecus kadabba fossils are close to Orrorin (others are more chimpanzee-like). -

Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) from the Upper

Geobios 50 (2017) 197–209 Available online at ScienceDirect www.sciencedirect.com Original article A new Elasmotheriini (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae) from the upper § Miocene of Samburu Hills and Nakali, northern Kenya a, b c d Naoto Handa *, Masato Nakatsukasa , Yutaka Kunimatsu , Hideo Nakaya a Museum of Osaka University, 1-20 Machikaneyama-cho, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-0043, Japan b Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kitashirakawa-oiwakecho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan c Faculty of Business Administration, Ryukoku University, 67 Tsukamoto-cho, Fukakusa, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto 612-8577, Japan d Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kagoshima University, 1-21-35 Korimoto, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Several rhinocerotid cheek teeth and mandibular fragments from the upper Miocene of the Samburu Received 15 August 2016 Hills and Nakali in northern Kenya are described. These specimens show characteristics that place them Accepted 20 April 2017 in the Tribe Elasmotheriini such as a constricted protocone, a developed antecrochet, and coronal Available online 8 May 2017 cement. The present specimens are compared with other Elasmotheriini species from Eurasia and sub- Saharan East Africa. They are found to be morphologically different from the previously known species of Keywords: Elasmotheriini. Morphologically, they are most similar to Victoriaceros kenyensis from the middle Elasmotheriini Miocene of Kenya, but differ from V. kenyensis in having the upper molars with the simple crochet, Rhinocerotidae lingual groove of the protocone and enamel ring in the medisinus. Therefore, the present specimens are Late Miocene assigned to a new genus and species of Elasmotheriini: Samburuceros ishidai. -

Fleagle and Lieberman 2015F.Pdf

15 Major Transformations in the Evolution of Primate Locomotion John G. Fleagle* and Daniel E. Lieberman† Introduction Compared to other mammalian orders, Primates use an extraordinary diversity of locomotor behaviors, which are made possible by a complementary diversity of musculoskeletal adaptations. Primate locomotor repertoires include various kinds of suspension, bipedalism, leaping, and quadrupedalism using multiple pronograde and orthograde postures and employing numerous gaits such as walking, trotting, galloping, and brachiation. In addition to using different locomotor modes, pri- mates regularly climb, leap, run, swing, and more in extremely diverse ways. As one might expect, the expansion of the field of primatology in the 1960s stimulated efforts to make sense of this diversity by classifying the locomotor behavior of living primates and identifying major evolutionary trends in primate locomotion. The most notable and enduring of these efforts were by the British physician and comparative anatomist John Napier (e.g., Napier 1963, 1967b; Napier and Napier 1967; Napier and Walker 1967). Napier’s seminal 1967 paper, “Evolutionary Aspects of Primate Locomotion,” drew on the work of earlier comparative anatomists such as LeGros Clark, Wood Jones, Straus, and Washburn. By synthesizing the anatomy and behavior of extant primates with the primate fossil record, Napier argued that * Department of Anatomical Sciences, Health Sciences Center, Stony Brook University † Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University 257 You are reading copyrighted material published by University of Chicago Press. Unauthorized posting, copying, or distributing of this work except as permitted under U.S. copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher. fig. 15.1 Trends in the evolution of primate locomotion. -

Forelimb Long Bones of Nacholapithecus (KNM-BG 35250) from the Middle Miocene in Nachola, Northern Kenya

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 126(3), 135–149, 2018 Forelimb long bones of Nacholapithecus (KNM-BG 35250) from the middle Miocene in Nachola, northern Kenya Tomo TAKANO1*, Masato NAKATSUKASA2, Yutaka KUNIMATSU3, Yoshihiko NAKANO4, Naomichi OGIHARA5**, Hidemi ISHIDA6 1Japan Monkey Centre, Kanrin 26, Inuyama, Aichi 484-0081, Japan 2Laboratory of Physical Anthropology, Graduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan 3Faculty of Business Administration, Ryukoku University, Kyoto 612-8577, Japan 4Laboratory of Biological Anthropology, Department of Human Science, Osaka University, Suita, Osaka 565-0871, Japan 5Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Science and Technology, Keio University, Yokohama, Kanagawa 223-8522, Japan 6Professor Emeritus, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan Received 1 May 2017; accepted 22 October 2018 Abstract This paper provides a thorough description of humeral, ulnar, and radial specimens of the Nacholapithecus holotype (KNM-BG 35250). A spool-shaped humeral trochlea (and keeled sigmoid notch of the ulna) is a hallmark of elbow joint evolution in hominoids. In lacking this feature, the elbow of Nacholapithecus is comparatively primitive, resembling that of proconsulids. However, the humer- oulnar joint in Nacholapithecus is specialized for higher stability than that in proconsulids. The humer- oradial joint (humeral capitulum) resembles that of extant apes and Sivapithecus. This condition may represent an intermediate stage leading to the fully modern elbow in extant apes. If this is the case, spe- cialization of the humeroradial joint preceded that of the humeroulnar joint. Nacholapithecus elbow joint morphology suggests more enhanced forearm rotation compared to proconsulids. This observation ac- cords with the forelimb-dominated positional behavior of Nacholapithecus relative to proconsulids, which has been proposed on the grounds of limb proportions and the morphology of the phalanges, shoulder girdle, and vertebrae. -

A New Late Miocene Great Ape from Kenya and Its Implications for the Origins of African Great Apes and Humans

A new Late Miocene great ape from Kenya and its implications for the origins of African great apes and humans Yutaka Kunimatsua,b, Masato Nakatsukasac, Yoshihiro Sawadad, Tetsuya Sakaid, Masayuki Hyodoe, Hironobu Hyodof, Tetsumaru Itayaf, Hideo Nakayag, Haruo Saegusah, Arnaud Mazurieri, Mototaka Saneyoshij, Hiroshi Tsujikawak, Ayumi Yamamotoa, and Emma Mbual aPrimate Research Institute, Kyoto University, Aichi 484-8506, Japan; cGraduate School of Science, Kyoto University, Kyoto 606-8502, Japan; dFaculty of Science and Engineering, Shimane University, Shimane 690-8504, Japan; eResearch Center for Inland Seas, Kobe University, Kobe 657-8501, Japan; fResearch Institute of Natural Sciences, Okayama University of Science, Okayama 700-0005, Japan; gFaculty of Science, Kagoshima University, Korimoto 1-21-35, Kagoshima 890-0065, Japan; hInstitute of Natural and Environmental Sciences, University of Hyogo, Sanda 669-1546, Japan; iE´ tudes Recherches Mate´riaux, 86022 Poitiers, France; jHayashibara Natural History Museum, Okayama 700-0907, Japan; kSchool of Medicine, Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8575, Japan; and lDepartment of Earth Sciences, National Museums of Kenya, P.O. Box 40658-00100, Nairobi, Kenya Edited by Alan Walker, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, and approved October 3, 2007 (received for review July 1, 2007) Extant African great apes and humans are thought to have di- (16, 17), in size and some morphological features, but a number verged from each other in the Late Miocene. However, few of differences lead us to assign the Nakali material to a different hominoid fossils are known from Africa during this period. Here we new genus. Nakalipithecus nakayamai and the associated primate describe a new genus of great ape (Nakalipithecus nakayamai gen. -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Moya` -Sola` et al. 10.1073/pnas.0811730106 SI Text netic relationships between all these taxa by classifying them all Systematic Framework. In Table S1 we provide a systematic into a single family Afropithecidae with 2 subfamilies (Keny- classification of living and fossil Hominoidea to the tribe level, apithecinae and Afropithecinae). by further including extant taxa and extinct genera discussed in The systematic scheme used here requires several nomencla- this paper. Hominoidea are defined as the group constituted by tural decisions, which deserve further explanation. The nomina Hylobatidae and Hominidae, plus all extinct taxa more closely Kenyapithecini and Kenyapithecinae are adopted instead of related to them than to Cercopithecoidea. Hominidae, in turn, Griphopithecinae and Griphopithecini (see also ref. 25) merely are defined as the group containing Ponginae and Homininae, because the former have priority. It is unclear why neither Begun plus all extinct forms more closely related to them than to (1) nor Kelley (2) specify the authorship of Griphopithecinae (or Hylobatidae. While this broad concept of Hominidae is currently Griphopithecidae), but, to our knowledge, the authorship of the used by many paleoprimatologists (e.g., refs. 1–2), the systematic latter nomina must be attributed to Begun (ref. 4, p. 232: Table position of primitive (or archaic) putative hominoids is far from 10.1), which therefore do not have priority over Kenyapithecinae clear (see below). Begun (3–5) employs the terms ‘‘Eohomi- Andrews, 1992. Griphopithecinae thus remains potentially valid noidea’’ and ‘‘Euhominoidea’’ to informally refer to hominoids only if Kenyapithecus (and Afropithecus, see below) are excluded of primitive and modern aspect, respectively.