Supporting Public Service Broadcasting Learning from Bosnia and Herzegovina’S Experience Acknowledgements 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Development of the Communication Regulatory

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Adin Sadic March 2006 2 This thesis entitled HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 by ADIN SADIC has been approved for the School of Telecommunications and the College of Communication by __________________________________________ Gregory Newton Associate Professor of Telecommunications __________________________________________ Gregory Shepherd Interim Dean, College of Communication 3 SADIC, ADIN. M.A. March 2006. Communication Studies History and Development of the Communication Regulatory Agency in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1998 – 2005 (247 pp.) Director of Thesis: Gregory Newton During the war against Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) over 250,000 people were killed, and countless others were injured and lost loved ones. Almost half of the B&H population was forced from their homes. The ethnic map of the country was changed drastically and overall damage was estimated at US $100 billion. Experts agree that misuse of the media was largely responsible for the events that triggered the war and kept it going despite all attempts at peace. This study examines and follows the efforts of the international community to regulate the broadcast media environment in postwar B&H. One of the greatest challenges for the international community in B&H was the elimination of hate language in the media. There was constant resistance from the local ethnocentric political parties in the establishment of the independent media regulatory body and implementation of new standards. -

2. Strategija Socijalne Uključenosti

IBHI Nezavisni biro za humanitarna pitanja Independent Bureau for Humanitarian Issues Safeta Hadžića 66A, 71000 Sarajevo Bosna i Hercegovina Tel: + 387 33 473 214 Fax: + 387 33 473 132 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.ibhibih.org Izdavač / Publisher Nezavisni biro za humanitarna pitanja - IBHI Urednica / Editor Ranka NINKOVIĆ-PAPIĆ Tehnički urednik / Technical Editor Dženan TRBIĆ Autori-ce / Authors Ana ABDELBASIT, Mira ĆUK, Demir IMAMOVIĆ, Ivan LOVRENOVIĆ, Žarko PAPIĆ, Vildana SELIMBEGOVIĆ, Azemina VUKOVIĆ Prevod / Translation Ana ABDELBASIT, Zemina BAHTO, Mirna KRŠLAK, Merima TAFRO Fotografija na naslovnoj strani / Cover page photo Damir ŠAGOLJ Dizajn naslovne strane / Cover design triptih, Sarajevo Štampa / Printing TDP d.o.o. Sarajevo Tiraž / Circulation 1000 Prvo izdanje / First Edition Sarajevo, februar/February 2009 Nezavisni biro za humanitarna pitanja (IBHI) zadržava autorska prava nad publikacijom. Citiranje navoda iz publikacije je dozvoljeno samo uz navođenje izvora: IBHI, Šta da se radi? Socijalna uključenost i civilno društvo – praktični koraci, (Sarajevo: IBHI, februar 2009. godine) The Independent Bureau for Humanitarian Issues (IBHI) reserves copyrights over this publication. Please cite source as: IBHI, What is to be Done? Social Inclusion and Civil Society – Practical Steps, (Sarajevo: IBHI, February 2009) Šta da se radi? Socijalna uključenost i civilno društvo – praktični koraci Sadržaj Ranka Ninković-Papić Predgovor ili pogled iznutra . 7 Azemina Vuković Jačanje civilnog društva: Naučene lekcije iz procesa pripreme BiH Strategije socijalnog uključivanja . 9 Žarko Papić Jačanje socijalnog uključivanja i NVO-a: Uloga NVO Fondacije za socijalno uključivanje . 32 Ana Abdelbasit 118 miliona koraka do saradnje . 55 Mira Ćuk Uloga i značaj lokalnih zajednica u procesu socijalnog uključivanja . 59 Demir Imamović Uloga civilnog društva u osiguranju i zaštiti prava na socijalnu uključenost . -

PUBLLISHED by Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’S Years on Trial

PUBLLISHED BY Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’s Years on Trial A collection of all the articles published by BIRN about Radovan Karadzic’s trial before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the UN’s International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals. This e-book contains news stories, analysis pieces, interviews and other articles on the trial of the former Bosnian Serb leader for crimes including genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Produced by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Introduction Radovan Karadzic was the president of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Repub- lika Srpska during wartime, when some of the most horrific crimes were committed on European soil since World War II. On March 20, 2019, the 73-year-old Karadzic faces his final verdict after being initially convicted in the court’s first-instance judgment in March 2016, and then appealing. The first-instance verdict found him guilty of the Srebrenica genocide, the persecution and extermination of Croats and Bosniaks from 20 municipal- ities across Bosnia and Herzegovina, and being a part of a joint criminal enterprise to terrorise the civilian population of Sarajevo during the siege of the city. He was also found guilty of taking UN peacekeepers hostage. Karadzic was initially indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in 1995. He then spent 12 years on the run, and was finally arrested in Belgrade in 2008 and extradited to the UN tribunal. As the former president of the Republika Srpska and the supreme com- mander of the Bosnian Serb Army, he was one of the highest political fig- ures indicted by the Hague court. -

The Media in Bosnia and Herzegovina: a Case Study of International Intervention in Media Democratization

The Media in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Case Study of International Intervention in Media Democratization Aleksandra Tomié Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal March 2002 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Aleksandra Tomié 2002 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 canada canada The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libnuy ofCanada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies oftbis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership ofthe L'auteur conselVe la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son pemnsslOn. autorisation. 0-612-79043-6 Canada ABSTRACT The thesis examines the work ofthe media in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the post-war period and efforts to restructure its institutions and change joumalistic practices. The main focus is placed the effort ofthe Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe to facilitate "free and fair elections" in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the creation of the Media Experts Commission, which was to regulate the work of the media during this period. -

Construction Media Assistance As a Tool of Post-Conflict

University of Graz A House of Cards: Bosnian media under (re)construction Media assistance as a tool of post-conflict democratization and state building Student: Niđara Ahmetašević Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Florian Bieber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy under the Joint PhD Programme in Diversity Management and Governance. Graz, June 2013 2 © 2013 Niđara Ametašević All rights reserved 3 ABSTRACT A House of Cards: Bosnian media under (re)construction Media assistance as a tool of post-conflict democratization and state building Niđara Ahmetašević Since the 1980s, media assistance is often used as a tool in democratization processes and state building in post-conflict or fragile states. A number of international organizations, governmental, non-governmental, or inter-governmental, foundations and professional organizations are getting involved in assisting media to develop, while sending material and technical support, offering trainings but also getting involved in the establishment of regulatory bodies, and introducing media laws. This method is yet not well researched, and its effectiveness is under the question in academia as well as by practitioners in the field. In this thesis, I explore whether media assistance was an effective tool of democratization and state-building in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country that became semi-protectorate after the signing of the Dayton Peace Accord. This thesis discuses if the imposition of the rules that regulate the media, can contribute to the process of democratization and state building, and look into how it affected professionalization of the media. The case of Bosnia is particularly indicative since it was one of the first and one of the biggest media assistance efforts, and some of the methods tested here have been transferred to other post-conflict countries, like Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq. -

Sustainability of Professional Journalism in the Media Business Environment of the Western Balkans

NATIONAL DATA OVERVIEW: BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA SUSTAINABILITY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISM IN THE MEDIA BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT OF THE WESTERN BALKANS This report is based on the Study that has been carried out by a team of researchers including: Lead researcher: Brankica Petković, Peace Institute, Ljubljana, Slovenia Regional researcher: Sanela Hodžić, Mediacentar, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina National researchers: Sanela Hodžić and Anida Sokol Language editing: Stephen Yeo, Michael Randall and Toby Vogel Research conducted: June-November 2019 Report published: June 2020 This research reflects the economic position and needs of independent media outlets in 2018 and 2019, with the majority of market data pertaining to 2018 and research being finalised in November 2019. The report does not cover the dramatic changes occurring in 2020, when the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic dealt yet another blow to media businesses and further diminished the pros- pects for sustainability of independent media in the Western Balkans. This document has been produced within the EU TACSO 3 project, under the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the team of researchers and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. Copyright notice © European Union, 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. It is in line with the: 1. EU communication and visibility requirements page 24 https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/communication-visibility-requirements-2018_ en.pdf 2. The new Copyright Directive from July 2020 https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_19_1151 Disclaimer This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. -

Appendix C-Focus

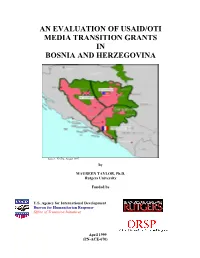

AN EVALUATION OF USAID/OTI MEDIA TRANSITION GRANTS IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Source: NATO, August 1997 by MAUREEN TAYLOR, Ph.D. Rutgers University Funded by U.S. Agency for International Development Bureau for Humanitarian Response Office of Transition Initiatives April 1999 (PN-ACE-670) LIST OF ACRONYMS....……............................………….........................................……...... ii MAP............................................…………..……….............................................................… iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................…………….............................................…….. iv I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND.........………......……........................………1 II. OTI STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES……………………………………………………….. 3 III. METHODOLOGY OF THE EVALUATION ………………………………….……… 4 IV. MEDIA TRANSITION GRANTS IN BOSNIAN FEDERATION ……………….……..6 Sarajevo ……………………………….………………………………………….……….6 Tuzla………………………………...…………………………….……………………. 10 Zenica……………………………………………………….……………………………13 V. MEDIA TRANSITION GRANTS IN REPUBLIKA SRPSKA………………...….……17 Banja Luka……………………………………………………………….……………... 17 VI. CONCLUSIONS...............……............................………………..........................……24 VII. LESSONS LEARNED.................................…………..……….....................................28 VIII. RECOMMENDATIONS……………...…………………..……………………………. 30 APPENDICES APPENDIX A: SITE VISITS WITH GRANTEES APPENDIX B: INTERVIEW SCHEDULE FOR GRANTEES APPENDIX C: FOCUS GROUP INTERVIEWS APPENDIX D: SURVEY DISTRRIBUTION APPENDIX E: SURVEY QUESTIONS APPENDIX -

Analysis of Public Criticism and Support of the Initiative for RECOM

Analysis of Public Criticism and Support of the Initiative for RECOM Igor Mekina / August 2011 The first report about the Initiative for the establishment of the Regional Commission for truth and truth-telling about war crimes in the former Yugoslavia was aired on Radio Free Europe on October 29, 2007. From then, until the end of August 2011, both print and electronic media published over 600 reports. These include, first and foremost, statements, interviews and opinions by advocates of RECOM; reviews of the Initiative; interviews with supporters or opponents of the idea of RECOM, articles, columns and op- eds; television and radio programs about RECOM; as well as various contributions directed against the Initiative. 1. Analysis objective and assessment criteria The main objective of this analysis is to investigate a number of critical evaluations and public controversies surrounding RECOM. In an effort to establish the truth, the analysis focuses on those contributions that launched a variety of charges against the Initiative for RECOM. The analysis comprises of more than 220 interviews, responses, articles, programs or written contributions in electronic media, all published on the website of the Initiative for RECOM (www.zarekom.org). In any evaluation of media coverage, truth is always the most important criterion. A commitment to truth and accuracy in reporting have been embraced in journalistic ethics as a basic obligation. From this obligation stem the fundamental principles of a journalistic code of ethics: journalists have a moral obligation to transmit, to the greatest extent possible, relevant and truthful information of public interest.1 For this reason, journalists are obliged to convey the truth as best as they can, to avoid intentional and unintentional falsehoods, recourse to prejudice and stereotypes, and to verify the veracity of others’ statements and allegations in order to detect and correct random or intentional errors. -

Sounds of Attraction

edited by Sounds of Attraction Miha Kozorog, Rajko Muršič Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Popular Music edited by Miha Kozorog and Rajko Muršič Miha Kozorog by edited Yugoslav and Post-Yugoslav Post-Yugoslav and Yugoslav Attraction Sounds ofSounds Popular Music Popular SOUNDS OF ATTRACTION: YUGOSLAV AND POST-YUGOSLAV POPULAR MUSIC Sounds of Attraction: Yugoslav and Published by/Založila: Znanstvena Post-Yugoslav Popular Music založba Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani (Ljubljana University Press, Uredila/Edited by Faculty of Arts) Miha Kozorog, Rajko Muršič Izdal/Issued by: Oddelek za etnologijo Recenzenta/Reviewers in kulturno antropologijo/ Svanibor Pettan Department of Ethnology and Cultural Jernej Mlekuž Anthropology Zbirka/Book series Za založbo/For the publisher Zupaničeva knjižnica, št. 43 Roman Kuhar, dekan Filozofske fakultete Univerze v Ljubljani/The Lektor/Proofreading dean of the Faculty of Arts, University Peter Altshul of Ljubljana Odgovorni urednik zbirke/ Ljubljana, 2017 Editor in chief Boštjan Kravanja Oblikovna zasnova zbirke/Design Vasja Cenčič Uredniški odbor zbirke/ Editorial board Bojan Baskar, Mateja Habinc, Vito Hazler, Jože Hudales, Božidar Jezernik, Delo je ponujeno pod licenco Creative Miha Kozorog, Boštjan Kravanja, Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 Uršula Lipovec Čebron, Ana Sarah International License (priznanje Lunaček Brumen, Mirjam Mencej, avtorstva, deljenje pod istimi pogoji). Rajko Muršič, Jaka Repič, Peter Simonič Prva izdaja, e-izdaja/ First edition/e-edition Fotografija na naslovnici/Cover photo Urša Valič Publikacija je na voljo na/Publication is available on: Vse pravice pridržane./ https://e-knjige.ff.uni-lj.si All rights reserved. DOI: 10.4312/9789612379643 Raziskovalni program št. P6-0187 je sofinancirala Javna agencija za raziskovalno dejavnost Republike Slovenije iz državnega Publikacija je brezplačna./Publication proračuna. -

Kas 20598-1522-2- 30.Pdf

Media Plan Institute in cooperation with the Konrad Adenauer Foundation’s Media Program for South East Europe implemented the project “The Internet: Freedom without Boundaries?” The goal of the project was to use results of monitoring and analysis of influential web portals to stimulate media professionalism and the public which uses the Internet in order to actively respect professional (journalistic) and ethical postulates of communication on the Internet. THE INTERNET - FREEDOM WITHOUT BOUNDARIES? Sarajevo, November 2010. Publisher: Media Plan Institute, Sarajevo [email protected] www.mediaplan.ba Editor: Radenko Udovicic [email protected] Translation from Bosnian: Kanita Halilovic Language of the edition: Bosnian, Serbian, Croatian (as chosen by the authors), English Cover and Layout: Mirza Latifovi} Print: CPU Sarajevo Circulation: 500 copies 2 THE INTERNET - FREEDOM WITHOUT BOUNDARIES? Sarajevo, November 2010. 3 THE INTERNET - FREEDOM WITHOUT BOUNDARIES? 4 Introduction Introduction DEPROFESSIONALIZATION OF COMMUNICATION Radenko Udovicic Information technologies are changing the lifestyle of individuals and the community. The internet has become the most democratic means of com- munication and offers unimagined development opportunities. Internet portals and websites of mainstream public media (press, radio and television) are increasingly occupying people’s attention. The trend of internet use in Bosnia-Herzegovina is rising. Portals are not just carries of information provided by news agencies and mainstream media; they are increasingly becoming exclusive sources of information in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Basically speaking, new media primarily means new channels of communi- cation. Whenever we start using old media in a new way, we get new media. This term is often used by popular journalism which by new media denotes the Internet, network sites, computers and computer games, as well as dif- ferent kinds of consoles (PS2 and 3, Nintendo), CD-ROMs, DVDs and so on. -

MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: BOSNIA and HERZEGOVINA Mapping Digital Media: Bosnia and Herzegovina

COUNTRY REPORT MAPPING DIGITAL MEDIA: BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Mapping Digital Media: Bosnia and Herzegovina A REPORT BY THE OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS WRITTEN BY Amer Dzˇihana (lead reporter) Kristina C´endic´ (reporter) Meliha Tahmaz (assistant reporter) EDITED BY Marius Dragomir and Mark Thompson (Open Society Media Program editors) EDITORIAL COMMISSION Yuen-Ying Chan, Christian S. Nissen, Dusˇan Reljic´, Russell Southwood, Michael Starks, Damian Tambini The Editorial Commission is an advisory body. Its members are not responsible for the information or assessments contained in the Mapping Digital Media texts OPEN SOCIETY MEDIA PROGRAM TEAM Meijinder Kaur, program assistant; Morris Lipson, senior legal advisor; and Gordana Jankovic, director OPEN SOCIETY INFORMATION PROGRAM TEAM Vera Franz, senior program manager; Darius Cuplinskas, director 11 June 2012 Contents Mapping Digital Media ..................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 6 Context ............................................................................................................................................. 10 Social Indicators ................................................................................................................................ 12 Economic Indicators ........................................................................................................................ -

Bih Media Round-Up, 20/5/2002

BiH Media Round-up, 20/5/2002 BiH State-related Issues Law on Succession adopted Belkic welcomes adoption of the Succession Law BiH Council of Ministers Chairman says adoption of succession law promotes cooperation with IMF Treasury Minister: BiH suffered damage of 15 million KM by sale of the gold PDHR Hays: BiH to face financial problems if fails to pass state Budget BiH Presidency adopts new draft Budget for 2002 SDA against erasing a provision on financing the lawsuit against FRY from the draft BiH Budget Judicial reform in BiH – Petritsch to remove corrupted judges Commercial media support formation of public radio-TV service BiH Election Commission President: a total of 57 parties and four independent candidates to run in the October elections CIPS project to be inaugurated, new ID card presented at a ceremony in Sarajevo on Monday BiH officials, US military company discuss single defense program State Border Service knows about smuggling at the Raca border crossing A conference on necessity of constitutional reforms held in Sarajevo Federation Vecernji List: Interview with Nikola Grabovac, the Federation Deputy Prime Minister and the Finance Minister Police arrest one, file charges against four in Mostar arms case Halilovic and Filipovic deny speculations on split-up inside the Alliance for Change SDA strongly condemns sale of Arab-donated weapons to Israel ONASA: Interview with Slavo Kukic, the President of the HPT Mostar Steering Board Vecernji List: Toby Robinson believes the third GSM license if given to Eronet rescues Hercegovacka