Analysis of Public Criticism and Support of the Initiative for RECOM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Development of the Communication Regulatory

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Adin Sadic March 2006 2 This thesis entitled HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 by ADIN SADIC has been approved for the School of Telecommunications and the College of Communication by __________________________________________ Gregory Newton Associate Professor of Telecommunications __________________________________________ Gregory Shepherd Interim Dean, College of Communication 3 SADIC, ADIN. M.A. March 2006. Communication Studies History and Development of the Communication Regulatory Agency in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1998 – 2005 (247 pp.) Director of Thesis: Gregory Newton During the war against Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) over 250,000 people were killed, and countless others were injured and lost loved ones. Almost half of the B&H population was forced from their homes. The ethnic map of the country was changed drastically and overall damage was estimated at US $100 billion. Experts agree that misuse of the media was largely responsible for the events that triggered the war and kept it going despite all attempts at peace. This study examines and follows the efforts of the international community to regulate the broadcast media environment in postwar B&H. One of the greatest challenges for the international community in B&H was the elimination of hate language in the media. There was constant resistance from the local ethnocentric political parties in the establishment of the independent media regulatory body and implementation of new standards. -

The Role of Churches and Religious Communities in Sustainable Peace Building in Southeastern Europe”

ROUND TABLE: “THE ROLE OF CHUrcHES AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES IN SUSTAINABLE PEACE BUILDING IN SOUTHEASTERN EUROPE” Under THE auSPICES OF: Mr. Terry Davis Secretary General of the Council of Europe Prof. Jean François Collange President of the Protestant Church of the Augsburg Confession of Alsace and Lorraine (ECAAL) President of the Council of the Union of Protestant Churches of Alsace and Lorraine President of the Conference of the Rhine Churches President of the Conference of the Protestant Federation in France Strasbourg, June 19th - 20th 2008 1 THE ROLE OF CHURCHES AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES IN SUSTAINABLE PEACE BUILDING PUBLISHER Association of Nongovernmental Organizations in SEE - CIVIS Kralja Milana 31/II, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia Tel: +381 11 3640 174 Fax: +381 11 3640 202 www.civis-see.org FOR PUBLISHER Maja BOBIć CHIEF EDITOR Mirjana PRLJević EDITOR Bojana Popović PROOFREADER Kate DEBUSSCHERE TRANSLATORS Marko NikoLIć Jelena Savić TECHNICAL EDITOR Marko Zakovski PREPRESS AND DESIGN Agency ZAKOVSKI DESIGN PRINTED BY FUTURA Mažuranićeva 46 21 131 Petrovaradin, Serbia PRINT RUN 1000 pcs YEAR August 2008. THE PUBLISHING OF THIS BOOK WAS supported BY Peace AND CRISES Management FOUndation LIST OF CONTEST INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 APPELLE DE STraSBOURG ..................................................................................................... 7 WELCOMING addrESSES ..................................................................................................... -

2. Strategija Socijalne Uključenosti

IBHI Nezavisni biro za humanitarna pitanja Independent Bureau for Humanitarian Issues Safeta Hadžića 66A, 71000 Sarajevo Bosna i Hercegovina Tel: + 387 33 473 214 Fax: + 387 33 473 132 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.ibhibih.org Izdavač / Publisher Nezavisni biro za humanitarna pitanja - IBHI Urednica / Editor Ranka NINKOVIĆ-PAPIĆ Tehnički urednik / Technical Editor Dženan TRBIĆ Autori-ce / Authors Ana ABDELBASIT, Mira ĆUK, Demir IMAMOVIĆ, Ivan LOVRENOVIĆ, Žarko PAPIĆ, Vildana SELIMBEGOVIĆ, Azemina VUKOVIĆ Prevod / Translation Ana ABDELBASIT, Zemina BAHTO, Mirna KRŠLAK, Merima TAFRO Fotografija na naslovnoj strani / Cover page photo Damir ŠAGOLJ Dizajn naslovne strane / Cover design triptih, Sarajevo Štampa / Printing TDP d.o.o. Sarajevo Tiraž / Circulation 1000 Prvo izdanje / First Edition Sarajevo, februar/February 2009 Nezavisni biro za humanitarna pitanja (IBHI) zadržava autorska prava nad publikacijom. Citiranje navoda iz publikacije je dozvoljeno samo uz navođenje izvora: IBHI, Šta da se radi? Socijalna uključenost i civilno društvo – praktični koraci, (Sarajevo: IBHI, februar 2009. godine) The Independent Bureau for Humanitarian Issues (IBHI) reserves copyrights over this publication. Please cite source as: IBHI, What is to be Done? Social Inclusion and Civil Society – Practical Steps, (Sarajevo: IBHI, February 2009) Šta da se radi? Socijalna uključenost i civilno društvo – praktični koraci Sadržaj Ranka Ninković-Papić Predgovor ili pogled iznutra . 7 Azemina Vuković Jačanje civilnog društva: Naučene lekcije iz procesa pripreme BiH Strategije socijalnog uključivanja . 9 Žarko Papić Jačanje socijalnog uključivanja i NVO-a: Uloga NVO Fondacije za socijalno uključivanje . 32 Ana Abdelbasit 118 miliona koraka do saradnje . 55 Mira Ćuk Uloga i značaj lokalnih zajednica u procesu socijalnog uključivanja . 59 Demir Imamović Uloga civilnog društva u osiguranju i zaštiti prava na socijalnu uključenost . -

The Letter of Support to the Initiative For

President of Kosovo, Mrs. Atifete Jahjaga Member of Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mr. Bakir Izetbegovic President of Serbia, Mr. Boris Tadic President of Slovenia, Mr. Danilo Turk President of Macedonia, Mr. Djordje Ivanov President of Montenegro, Mr. Filip Vujanovic President of Croatia, Mr. Ivo Josipovic Member of Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mr. Nebojsa Radmanovic Member of Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Mr. Zeljko Komsic Subject: Establishment of RECOM Sarajevo, Belgrade, Prishtina, Zagreb, Skopje, Podgorica, Ljubljana October 2011 Your Excellencies, Presidents and Members of Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, We believe that citizens of the countries of the former Yugoslavia have a need and the right to know all the facts about war crimes and other massive human rights violations committed during the wars of the 1990s. They also have the right and a need, we believe, to know the consequences of those wars. This is why we are writing to you. For over a decade, since the weapons have been muted, post-Yugoslav societies have not been able to cope with the heavy legacy of the war past, largely because the fate of a number of those killed, forcibly disappeared, tortured, and persecuted – the people who suffered in so many different, horrible ways – remains unknown to date. Only a few names of those who died are known, but more than 13,000 families of forcibly disappeared persons are still searching for their loved ones. On top of this, there is no organized, systematic mechanism for the victims to seek and obtain fair reparation; and the lack of reliable facts about the victims is continually used for political manipulation, nationalist promotion, hatred and intolerance. -

Bosnia Doesn’T Work 15 Michael Schmunk

Table of Contents Foreword by the Editors 5 Ernst M. Felberbauer, Predrag Jureković and Frederic Labarre Welcome Speech 7 Johann Pucher PART I: OVERCOMING POLITICAL OBSTACLES, FACING ECONOMIC CHALLENGES 13 A Country with Several Nations, but Without a Proper State? Why Bosnia Doesn’t Work 15 Michael Schmunk Multiple Faces of the Bosnian ”Crisis Circle”: Ethnonationalism and Ethnopolitics in Post-Dayton-Bosnia and their Effects on Democratization 31 Vedran Džihić PART II: REGIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL FACTORS OF INFLUENCE 55 Bosnia: Hostage of Belgrade 57 Sonja Biserko The Regional Cooperation Council’s Role 63 Alphan Solen NATO and Reform in Bosnia-Herzegovina 67 Bruce McLane PART III: RELEVANT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE SECURITY SECTOR 77 The Challenge of Reaching Self Sustainability in a Post-War Environment 79 Denis Hadžović 3 The Next Step in Defence Reform: Establishing a Military Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina 91 Heinz Vetschera The Religious Radicalism and its Impact on the Security Development in Bosnia and Herzegovina 113 Velko Attanassoff Recent Developments in Fighting Organized Crime in Bosnia- Herzegovina 131 Stephen Alexander Goddard PART IV: SOCIAL BARRIERS AND WAYS OF DEALING WITH THEM 145 Lessons of Peacebuilding for the Balkans and Beyond: Towards a Culture of Dialogue, Reconciliation and Transformation 147 Dennis J.D. Sandole The Role of Media in the Process of Peace-Building 177 Drago Pilsel The Role of Education for Sustainable Peace-Building 183 Wolfgang Benedek PART VI: CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 205 Conclusions and Recommendations 207 Predrag Jureković List of Authors and Editors 217 4 Foreword by the Editors Bosnia and Herzegovina in almost 14 years of the post-Dayton period has not become a functional state despite some successes that have been achieved in regard to the Euro-Atlantic integration processes. -

PUBLLISHED by Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’S Years on Trial

PUBLLISHED BY Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’s Years on Trial A collection of all the articles published by BIRN about Radovan Karadzic’s trial before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the UN’s International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals. This e-book contains news stories, analysis pieces, interviews and other articles on the trial of the former Bosnian Serb leader for crimes including genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Produced by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Introduction Radovan Karadzic was the president of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Repub- lika Srpska during wartime, when some of the most horrific crimes were committed on European soil since World War II. On March 20, 2019, the 73-year-old Karadzic faces his final verdict after being initially convicted in the court’s first-instance judgment in March 2016, and then appealing. The first-instance verdict found him guilty of the Srebrenica genocide, the persecution and extermination of Croats and Bosniaks from 20 municipal- ities across Bosnia and Herzegovina, and being a part of a joint criminal enterprise to terrorise the civilian population of Sarajevo during the siege of the city. He was also found guilty of taking UN peacekeepers hostage. Karadzic was initially indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in 1995. He then spent 12 years on the run, and was finally arrested in Belgrade in 2008 and extradited to the UN tribunal. As the former president of the Republika Srpska and the supreme com- mander of the Bosnian Serb Army, he was one of the highest political fig- ures indicted by the Hague court. -

The Media in Bosnia and Herzegovina: a Case Study of International Intervention in Media Democratization

The Media in Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Case Study of International Intervention in Media Democratization Aleksandra Tomié Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal March 2002 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Aleksandra Tomié 2002 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 canada canada The author has granted a non L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libnuy ofCanada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies oftbis thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership ofthe L'auteur conselVe la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son pemnsslOn. autorisation. 0-612-79043-6 Canada ABSTRACT The thesis examines the work ofthe media in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the post-war period and efforts to restructure its institutions and change joumalistic practices. The main focus is placed the effort ofthe Organization of Security and Cooperation in Europe to facilitate "free and fair elections" in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the creation of the Media Experts Commission, which was to regulate the work of the media during this period. -

Construction Media Assistance As a Tool of Post-Conflict

University of Graz A House of Cards: Bosnian media under (re)construction Media assistance as a tool of post-conflict democratization and state building Student: Niđara Ahmetašević Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Florian Bieber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy under the Joint PhD Programme in Diversity Management and Governance. Graz, June 2013 2 © 2013 Niđara Ametašević All rights reserved 3 ABSTRACT A House of Cards: Bosnian media under (re)construction Media assistance as a tool of post-conflict democratization and state building Niđara Ahmetašević Since the 1980s, media assistance is often used as a tool in democratization processes and state building in post-conflict or fragile states. A number of international organizations, governmental, non-governmental, or inter-governmental, foundations and professional organizations are getting involved in assisting media to develop, while sending material and technical support, offering trainings but also getting involved in the establishment of regulatory bodies, and introducing media laws. This method is yet not well researched, and its effectiveness is under the question in academia as well as by practitioners in the field. In this thesis, I explore whether media assistance was an effective tool of democratization and state-building in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country that became semi-protectorate after the signing of the Dayton Peace Accord. This thesis discuses if the imposition of the rules that regulate the media, can contribute to the process of democratization and state building, and look into how it affected professionalization of the media. The case of Bosnia is particularly indicative since it was one of the first and one of the biggest media assistance efforts, and some of the methods tested here have been transferred to other post-conflict countries, like Kosovo, Afghanistan, Iraq. -

Sustainability of Professional Journalism in the Media Business Environment of the Western Balkans

NATIONAL DATA OVERVIEW: BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA SUSTAINABILITY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISM IN THE MEDIA BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT OF THE WESTERN BALKANS This report is based on the Study that has been carried out by a team of researchers including: Lead researcher: Brankica Petković, Peace Institute, Ljubljana, Slovenia Regional researcher: Sanela Hodžić, Mediacentar, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina National researchers: Sanela Hodžić and Anida Sokol Language editing: Stephen Yeo, Michael Randall and Toby Vogel Research conducted: June-November 2019 Report published: June 2020 This research reflects the economic position and needs of independent media outlets in 2018 and 2019, with the majority of market data pertaining to 2018 and research being finalised in November 2019. The report does not cover the dramatic changes occurring in 2020, when the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic dealt yet another blow to media businesses and further diminished the pros- pects for sustainability of independent media in the Western Balkans. This document has been produced within the EU TACSO 3 project, under the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the team of researchers and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. Copyright notice © European Union, 2020 Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. It is in line with the: 1. EU communication and visibility requirements page 24 https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/communication-visibility-requirements-2018_ en.pdf 2. The new Copyright Directive from July 2020 https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_19_1151 Disclaimer This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. -

Novinarskog Druπtva I Sindikata Novinara Hrvatske Poπtarina Plaêena U Poπtanskom Uredu 51000 Rijeka Novinarfoto SINI©A SUNARA

broj 7/8/9/2010. glasilo Hrvatskog novinarskog druπtva i Sindikata novinara Hrvatske Poπtarina plaÊena u poπtanskom uredu 51000 Rijeka novinarfoto SINI©A SUNARA speluj mejesu njeæno li novinaritko mazohisti to jede iz ruke Ëilost i boljke stogodiπnjaka o dobro • journalism - public good • novinarstvo - javno dobro • journalism - public good novinarstvo - javno dobro • journalism - publicU povodu good • novinarstvo - javno dobro • journalism - public good • novinarstvo - javno dobro • journalism - public good • novinarstvo - javno dobro • journalism - public good stote obljetnice HND-a SADRÆAJ 3 2 SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ U povodu stote obljetnice HND-a »ilost i boljke zrelog stogodiπnjaka Zdenko Duka str. 4. SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ broj 7/8/9/2010. broj 7/8/9/2010. broj novinar novinar Javno financiranje medija Vaæno je imati kriterije Toni GabriÊ str. 6. SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ Okrugli stol Manjine na medijskoj margini Milan Cimeπa str. 9. SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SluËajevi Gorana MiliÊa i Æarka Domljana str.10. SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ SADRÆAJ Struka na raskrπÊu Povratak korijenima Milivoj –ilas str. -

Supporting Public Service Broadcasting Learning from Bosnia and Herzegovina’S Experience Acknowledgements 2

United Nations Development Programme Bureau for Development Policy Democratic Governance Group Supporting Public Service Broadcasting Learning from Bosnia and Herzegovina’s experience Acknowledgements 2 Acknowledgements This document has been developed by Alexandra Wilde, a Research Associate at the UNDP Oslo Governance Centre (OGC), a unit of the Democratic Governance Group (DGG) in collaboration with Elizabeth McCall, Civil Society Adviser at the OGC. The paper takes account of substantive comments received from colleagues within DGG, as well as from selected international specialists in broadcasting reform including from Article 19 (Andrew Puddpehatt), the Sarajevo Media Centre (Boro Kontic), the BBC World Service Trust and the BBC Bosnia Consultancy in Bosnia) and Ross Howard at the Institute for Media, Policy and Civil Society (IMPACS). The paper is also informed by consultations with representatives from Civil Society Organisations and the public service broadcasting and commercial broadcasting sectors in Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as key donors such as the EC and Japan. It also reflects comments received from Pauline Wilson, an independent consultant with extensive expertise in civil society and poverty issues. The paper benefits from the expertise, experience and assistance from UNDP Country office staff in Sarajevo, especially Hideko Shimoji, Moises Venancio and Ubavka Dizdarevic. Further advice and information can be obtained from the Democratic Governance Group of UNDP. Contact Elizabeth McCall, Civil Society/ Access to Information Advisor at [email protected]. October 2004 UNDP is the UN’s global development network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. We are on the ground in 166 countries, working with them on their own solutions to global and national development challenges. -

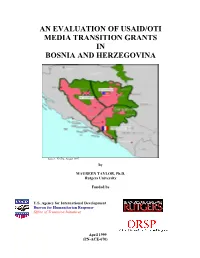

Appendix C-Focus

AN EVALUATION OF USAID/OTI MEDIA TRANSITION GRANTS IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Source: NATO, August 1997 by MAUREEN TAYLOR, Ph.D. Rutgers University Funded by U.S. Agency for International Development Bureau for Humanitarian Response Office of Transition Initiatives April 1999 (PN-ACE-670) LIST OF ACRONYMS....……............................………….........................................……...... ii MAP............................................…………..……….............................................................… iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................…………….............................................…….. iv I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND.........………......……........................………1 II. OTI STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES……………………………………………………….. 3 III. METHODOLOGY OF THE EVALUATION ………………………………….……… 4 IV. MEDIA TRANSITION GRANTS IN BOSNIAN FEDERATION ……………….……..6 Sarajevo ……………………………….………………………………………….……….6 Tuzla………………………………...…………………………….……………………. 10 Zenica……………………………………………………….……………………………13 V. MEDIA TRANSITION GRANTS IN REPUBLIKA SRPSKA………………...….……17 Banja Luka……………………………………………………………….……………... 17 VI. CONCLUSIONS...............……............................………………..........................……24 VII. LESSONS LEARNED.................................…………..……….....................................28 VIII. RECOMMENDATIONS……………...…………………..……………………………. 30 APPENDICES APPENDIX A: SITE VISITS WITH GRANTEES APPENDIX B: INTERVIEW SCHEDULE FOR GRANTEES APPENDIX C: FOCUS GROUP INTERVIEWS APPENDIX D: SURVEY DISTRRIBUTION APPENDIX E: SURVEY QUESTIONS APPENDIX