Construction Media Assistance As a Tool of Post-Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History and Development of the Communication Regulatory

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Adin Sadic March 2006 2 This thesis entitled HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE COMMUNICATION REGULATORY AGENCY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA 1998 – 2005 by ADIN SADIC has been approved for the School of Telecommunications and the College of Communication by __________________________________________ Gregory Newton Associate Professor of Telecommunications __________________________________________ Gregory Shepherd Interim Dean, College of Communication 3 SADIC, ADIN. M.A. March 2006. Communication Studies History and Development of the Communication Regulatory Agency in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1998 – 2005 (247 pp.) Director of Thesis: Gregory Newton During the war against Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H) over 250,000 people were killed, and countless others were injured and lost loved ones. Almost half of the B&H population was forced from their homes. The ethnic map of the country was changed drastically and overall damage was estimated at US $100 billion. Experts agree that misuse of the media was largely responsible for the events that triggered the war and kept it going despite all attempts at peace. This study examines and follows the efforts of the international community to regulate the broadcast media environment in postwar B&H. One of the greatest challenges for the international community in B&H was the elimination of hate language in the media. There was constant resistance from the local ethnocentric political parties in the establishment of the independent media regulatory body and implementation of new standards. -

Čertovy Obrázky V Historii a Současnosti (Výtvarná Realizace Mariášových Karet)

Jihočeská univerzita v Českých Budějovicích Pedagogická fakulta České Budějovice 2007 Diplomová práce ČERTOVY OBRÁZKY V HISTORII A SOUČASNOSTI (VÝTVARNÁ REALIZACE MARIÁŠOVÝCH KARET) The Devil’s Books in History and Present (Art Realisation of Whist Cards) Autor: Vendula Smilová Vedoucí diplomové práce: doc. PaedDr. Matouš Vondrák, CSc. Anotace Tato diplomová práce se skládá ze dvou základních částí. Z části teoretické, kterou právě držíte v ruce a z části praktické, kterou najdete ve zmenšené verzi reprodukova- nou v obrazové příloze a jejíž originály budou prezentovány při její obhajobě. V praktické části své práce jsem vytvořila kompletní soubor mariášových karet, technikou kolorovaného linorytu. V teoretickém doprovodu výtvarné části se zabývám historií a současností karetní hry. Dočtete se o původu karet, o jejich cestě na evropský kontinent a jejich putování po něm, o kartách v českých zemích a o současném karetním světě. Dále se věnuji druhům karet, zejména kartám mariášovým (ty dokonce tvoří samostatnou kapitolu), karetním hrám (především hrám na našem území a hrám hraným mariášovými kartami), techno- logii výroby karetních listů a hráčům. Celou jednu kapitolu jsem pak zasvětila povídání o mé praktické realizaci kolekce mariášových karet, kde objasňuji jak volbu tématu, tak vznik jednotlivých figur a barevnost. Annotation This diploma thesis consists of two basic parts. The theoretical part, which you hold in your hands just now, and the practical part, which you can find in reduced ver- sion in the image supplement of this work and whose originals will be presented by the day of the diploma thesis defence session. In practical part of my work I have created a full collection of the whist cards using coloured lino-cut technology. -

PDF Download

30 June 2020 ISSN: 2560-1628 2020 No. 26 WORKING PAPER Belt and Road Initiative and Platform “17+1”: Perception and Treatment in the Media in Bosnia and Herzegovina Igor Soldo Kiadó: Kína-KKE Intézet Nonprofit Kft. Szerkesztésért felelős személy: Chen Xin Kiadásért felelős személy: Wu Baiyi 1052 Budapest Petőfi Sándor utca 11. +36 1 5858 690 [email protected] china-cee.eu Belt and Road Initiative and Platform “17+1”: Perception and Treatment in the Media in Bosnia and Herzegovina Igor Soldo Head of the Board of Directors, Foundation for the Promotion and Development of the Belt and Road Initiative, BiH Abstract The Belt and Road Initiative, as well as cooperation China - Central and Eastern European Countries (hereinafter: CEE) through the Platform "17+1" require the creation of a higher level of awareness of citizens about all aspects of the advantages of these foreign policy initiatives aimed at mutual benefit for both China and the participating countries. Of course, the media always play a key role in providing quality information to the general public, with the aim of better understanding all the benefits that these Chinese initiatives can bring to Bosnia and Herzegovina. Also, the media can have a great influence on decision makers by creating a positive environment and by accurate and objective information. Therefore, when it comes to media articles related to these topics, it is important to look at the situation objectively and professionally. The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of the media treatment of the Belt and Road Initiative and Platform "17+1" in Bosnia and Herzegovina, quantitative measuring of the total number of media releases dealing with these topics in the media with editorial board or visible editorial policy, and their qualitative analysis, as well as the analysis of additional, special relevant articles. -

Tekstovi Iz Ovog Biltena Su Za Internu Upotrebu I Ne Mogu Se Javno

71000 Sarajevo, BiH, Patriotske lige 30/III (Arhitektonski fakultet) http://www.mp-institut.com/ [email protected] tel/fax:++387 (0)71 206 542, 213 078 ANALYSIS OF THE MEDIA SITUATION IN BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA IN 1997 Author: Media Plan analytic-research team Chief analyst: Zoran Udovicic Based on: Media Plan documentation Date: December/January 1997/1998 1. Overview of development1 * The conditions in which the media in Bosnia-Herzegovina operate are very dynamic. In the past years, the media situation has radically changed. The first turnabout took place in 1990 when the dissolution of the socialist system began. New papers of a critical orientation were launched and a generation of young, nonconformist journalists developed. Many of them even today make up the nucleus of the liberal and professionally reputable papers. The media ownership transformation also began. The first multi-party elections were held in the fall of 1990. At that time, national homogenization was carried out to a large extent in the entire Yugoslavia. Yugoslavia’s disintegration began. The national parties which won the elections in Bosnia-Herzegovina were trying to obtain positions for themselves in the media. Many media organizations changed their 1 Monitoring Report series I and II (June 1996 – June 1997); Elections 96 – Media Monitoring Report, January 1996; Report on the Media Situation in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Media Plan / Reporters without Borders, Paris, January 1997; monthly media report of Media Plan, July 1997. patrons – from the hands of the communist authorities they went into the hands of the ruling national parties. In mid-1991, 377 newspapers and other editions were registered in Bosnia-Herzegovina, as well as 54 local radio stations, four TV stations, one news agency and the state RTV network with three channels. -

2. Strategija Socijalne Uključenosti

IBHI Nezavisni biro za humanitarna pitanja Independent Bureau for Humanitarian Issues Safeta Hadžića 66A, 71000 Sarajevo Bosna i Hercegovina Tel: + 387 33 473 214 Fax: + 387 33 473 132 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.ibhibih.org Izdavač / Publisher Nezavisni biro za humanitarna pitanja - IBHI Urednica / Editor Ranka NINKOVIĆ-PAPIĆ Tehnički urednik / Technical Editor Dženan TRBIĆ Autori-ce / Authors Ana ABDELBASIT, Mira ĆUK, Demir IMAMOVIĆ, Ivan LOVRENOVIĆ, Žarko PAPIĆ, Vildana SELIMBEGOVIĆ, Azemina VUKOVIĆ Prevod / Translation Ana ABDELBASIT, Zemina BAHTO, Mirna KRŠLAK, Merima TAFRO Fotografija na naslovnoj strani / Cover page photo Damir ŠAGOLJ Dizajn naslovne strane / Cover design triptih, Sarajevo Štampa / Printing TDP d.o.o. Sarajevo Tiraž / Circulation 1000 Prvo izdanje / First Edition Sarajevo, februar/February 2009 Nezavisni biro za humanitarna pitanja (IBHI) zadržava autorska prava nad publikacijom. Citiranje navoda iz publikacije je dozvoljeno samo uz navođenje izvora: IBHI, Šta da se radi? Socijalna uključenost i civilno društvo – praktični koraci, (Sarajevo: IBHI, februar 2009. godine) The Independent Bureau for Humanitarian Issues (IBHI) reserves copyrights over this publication. Please cite source as: IBHI, What is to be Done? Social Inclusion and Civil Society – Practical Steps, (Sarajevo: IBHI, February 2009) Šta da se radi? Socijalna uključenost i civilno društvo – praktični koraci Sadržaj Ranka Ninković-Papić Predgovor ili pogled iznutra . 7 Azemina Vuković Jačanje civilnog društva: Naučene lekcije iz procesa pripreme BiH Strategije socijalnog uključivanja . 9 Žarko Papić Jačanje socijalnog uključivanja i NVO-a: Uloga NVO Fondacije za socijalno uključivanje . 32 Ana Abdelbasit 118 miliona koraka do saradnje . 55 Mira Ćuk Uloga i značaj lokalnih zajednica u procesu socijalnog uključivanja . 59 Demir Imamović Uloga civilnog društva u osiguranju i zaštiti prava na socijalnu uključenost . -

The Penguin Book of Card Games

PENGUIN BOOKS The Penguin Book of Card Games A former language-teacher and technical journalist, David Parlett began freelancing in 1975 as a games inventor and author of books on games, a field in which he has built up an impressive international reputation. He is an accredited consultant on gaming terminology to the Oxford English Dictionary and regularly advises on the staging of card games in films and television productions. His many books include The Oxford History of Board Games, The Oxford History of Card Games, The Penguin Book of Word Games, The Penguin Book of Card Games and the The Penguin Book of Patience. His board game Hare and Tortoise has been in print since 1974, was the first ever winner of the prestigious German Game of the Year Award in 1979, and has recently appeared in a new edition. His website at http://www.davpar.com is a rich source of information about games and other interests. David Parlett is a native of south London, where he still resides with his wife Barbara. The Penguin Book of Card Games David Parlett PENGUIN BOOKS PENGUIN BOOKS Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia) Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia -

Contemporary Nostalgia

Contemporary Nostalgia Edited by Niklas Salmose Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Humanities www.mdpi.com/journal/humanities Contemporary Nostalgia Contemporary Nostalgia Special Issue Editor Niklas Salmose MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade Special Issue Editor Niklas Salmose Linnaeus University Sweden Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Humanities (ISSN 2076-0787) from 2018 to 2019 (available at: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/ humanities/special issues/Contemporary Nostalgia). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Article Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-03921-556-0 (Pbk) ISBN 978-3-03921-557-7 (PDF) Cover image courtesy of Wikimedia user jarekt. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/ wiki/File:Cass Scenic Railroad State Park - Shay 11 - 05.jpg. c 2019 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Special Issue Editor ...................................... vii Niklas Salmose Nostalgia Makes Us All Tick: A Special Issue on Contemporary Nostalgia Reprinted from: Humanities 2019, 8, 144, doi:10.3390/h8030144 ................... -

Zbornik Srebrenica

IZDAVAČ: Univerzitet u Sarajevu Institut za istraživanje zločina protiv čovječnosti i međunarodnog prava ZA IZDAVAČA: Dr. Rasim Muratović, naučni savjetnik UREDNICI: Dr. Fikret Bečirović Mr. Muamer Džananović DTP: Dipl. ing. Sead Muhić NASLOVNA STRANA: Dipl. ing. Sead Muhić ŠTAMPA: Štamparija Fojnica d.o.o. TIRAŽ: 300 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- CIP - Katalogizacija u publikaciji Nacionalna i univerzitetska biblioteka Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- “SREBRENICA 1995-2015: EVALUACIJA N A S L I J E Đ A I D U G O R O Č N I H POSLJEDICA GENOCIDA” Zbornik radova sa Međunarodne naučne k o n f e r e n c i j e o d r ž a n e 9 - 1 1 . j u l a 2 0 1 5 . g o d i n e Sarajevo – Tuzla – Srebrenica (Potočari): 9-11. juli 2015. Sarajevo, 2016. SADRŽAJ II K NJ I G A Kuka, Ermin, Značaj i uloga edukacije o genocidu u sigurnoj zoni UN-a Srebrenici, jula 1995. godine ..................11 Kurtćehajić, Suad, Genocid u Srebrenici kao osnov poništenja Dejtonskog mirovnog sporazuma .............................20 Kurtović, Rejhan, Deklaracija o Srebrenici između potreba i stvarnosti ...................................................................................31 Lapandić, Nermin, Jedanaesta faza genocida u Bosni i Hercegovini ................................................................................46 Mahmutović, Muhamed, Srebrenica - genocid kojeg nema u školskim udžbenicima! ...............................................................70 -

Izvještaj O Izrečenim Izvršnim Mjerama Regulatorne Agencije Za Komunikacije Za 2020

IZVJEŠTAJ O IZREČENIM IZVRŠNIM MJERAMA REGULATORNE AGENCIJE ZA KOMUNIKACIJE ZA 2020. GODINU april, 2021. godine SADRŽAJ: 1. UVOD .............................................................................................................................. 3 2. PREGLED KRŠENJA I IZREČENIH IZVRŠNIH MJERA ............................................................. 5 2.1 KRŠENJA KODEKSA O AUDIOVIZUELNIM MEDIJSKIM USLUGAMA I MEDIJSKIM USLUGAMA RADIJA ......... 5 2.2 KRŠENJA KODEKSA O KOMERCIJALNIM KOMUNIKACIJAMA .................................................................... 15 2.3 KRŠENJA PRAVILA O PRUŽANJU AUDIOVIZUELNIH MEDIJSKIH USLUGA I PRAVILA O PRUŽANJU MEDIJSKIH USLUGA RADIJA................................................................................................................................................. 19 2.4 KRŠENJA PRAVILA 79/2016 O DOZVOLAMA ZA DISTRIBUCIJU AUDIOVIZUELNIH MEDIJSKIH USLUGA I MEDIJSKIH USLUGA RADIJA ............................................................................................................................... 24 2.5 KRŠENJA ODREDBI IZBORNOG ZAKONA BiH ............................................................................................. 26 2.6 KRŠENJA PRAVILA I PROPISA U OBLASTI TEHNIČKIH PARAMETARA DOZVOLA ZA PRUŽANJE AVM USLUGA KOJI USLUGE PRUŽAJU PUTEM ZEMALJSKE RADIODIFUZIJE .............................................................................. 29 3. SAŽETAK ....................................................................................................................... -

Illustrative Probability Theory

http://math.uni-pannon.hu/~szalkai/Illustrative-PrTh-1.pdf 181102 Illustrative Probability Theory by István Szalkai, Veszprém, University of Pannonia, Veszprém, Hungary The original "Hungarian" deck of cards, from 1835 Note: This is a very short summary for better understanding. N and R denote the sets of natural and real numbers, □ denotes the end of theorems, proofs, remarks, etc., in quotation marks ("...") we also give the Hungarian terms /sometimes interchanged/. Further materials can be found on my webpage http://math.uni-pannon.hu/~szalkai in the Section "Valószínűségszámítás". dr. Szalkai István, [email protected] Veszprém, 2018.11.01. Content: 0. Prerequisites p. 3. 1. Events and the sample space p. 5. 2. The relative frequency and the probability p. 8. 3. Calculating the probability p. 9. 4. Conditional probability, independence of events p. 10. 5. Random variables and their characteristics p. 14. 6. Expected value, variance and dispersion p. 18. 7. Special discrete random variables p. 21. 8. Special continous random variables p. 27. 9. Random variables with normal distribution p. 29. 10. Law of large numbers p. 34. 11. Appendix Probability theory - Mathematical dictionary p. 37. Table of the standard normal distribution function () p. 38. Bibliography p. 40. Biographies p. 40. 2 0. Prerequisites Elementary combintorics and counting techniques. Recall and repeat your knowledge about combinatorics from secondary school: permuta- tions, variations, combinations, factorials, the binomial coefficients ("binomiális együtthatók") n n(n 1)...(n k 1) k k! and their basic properties, the Pascal triangle, Newton's binomial theorem. The above formula is defined for all natural numbers n,kN . -

Analysis of the Media Reporting Corruption In

ANALYSIS OF THE MEDIA REPORTING CORRUPTION IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA (15 -28. August, 2011.) Meše Selimovića 55 | Banja Luka 78000 | [email protected] | T: +387 51 221 920 | F: +387 51 221 921 | 033 222 152 | Soukbunar 42 | Sarajevo 71 000 | [email protected] | T: +387 33 200 653 | T/F: +387 33 222 152 www.prime.ba PIB: 401717540009 | JIB: 4401717540009 | JIB PJ 4401717540017 | Matični broj: 1971158 METHODOLOGICAL NOTES The basis of this analysis is the media reporting in the form of news genres or press releases whose content was dedicated to corruption in Bosnia and Herzegovina (examples of corruptive actions, research and reports on the level of corruption distribution, activities towards legal proceedings and prevention of corruption, etc.). While analyzing the media excerpts, attention was aimed toward determining the qualifications of the mentioned corruptive activities, i.e., the way they were mentioned and interpreted – who is the one that points out to the examples of corruption, who interprets them, and who is named as the perpetrator of these actions. The analysis included 135 texts and features from 9 daily newspapers (Dnevni avaz, Dnevni list, Euro Blic, Fokus, Glas Srpske, Nezavisne novine, Oslobodjenje, Press, Vecernji list), 2 weekly papers (Dani, Slobodna Bosna), 3 television stations (news programme of BHT, FTV, and RTRS, with two features from OBN and TV SA) and 7 web sites (24sata.info, bih.x.info, biznis.ba, depo.ba, dnevnik-ba, Sarajevo-x.com, zurnal.info) in the period between August 15 and 28, 2011. The excerpts were cross-referenced with each date during the analyzed period in order to estimate their frequency in newspapers, assuming that the frequency is one of the indicators of importance of the topic of corruption. -

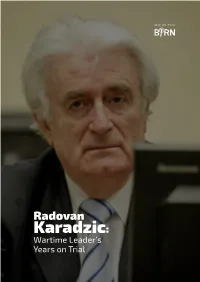

PUBLLISHED by Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’S Years on Trial

PUBLLISHED BY Radovan Karadzic: Wartime Leader’s Years on Trial A collection of all the articles published by BIRN about Radovan Karadzic’s trial before the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the UN’s International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals. This e-book contains news stories, analysis pieces, interviews and other articles on the trial of the former Bosnian Serb leader for crimes including genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity during the conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Produced by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. Introduction Radovan Karadzic was the president of Bosnia’s Serb-dominated Repub- lika Srpska during wartime, when some of the most horrific crimes were committed on European soil since World War II. On March 20, 2019, the 73-year-old Karadzic faces his final verdict after being initially convicted in the court’s first-instance judgment in March 2016, and then appealing. The first-instance verdict found him guilty of the Srebrenica genocide, the persecution and extermination of Croats and Bosniaks from 20 municipal- ities across Bosnia and Herzegovina, and being a part of a joint criminal enterprise to terrorise the civilian population of Sarajevo during the siege of the city. He was also found guilty of taking UN peacekeepers hostage. Karadzic was initially indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia in 1995. He then spent 12 years on the run, and was finally arrested in Belgrade in 2008 and extradited to the UN tribunal. As the former president of the Republika Srpska and the supreme com- mander of the Bosnian Serb Army, he was one of the highest political fig- ures indicted by the Hague court.