The Terraced Landscape in a Study of Historical Geography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comune Di Favale Di Malvaro Statuto

COMUNE DI FAVALE DI MALVARO STATUTO Approvato con Delibera del Consiglio Comunale n°37 del 28/12/1999 Modificato con Delibera del Consiglio Comunale n° 02 del 28/02/2000 TITOLO I PRINCIPI GENERALI Art. 1 – Autonomia statutaria 1. Il Comune di Favale di Malvaro è un Ente Locale autonomo, rappresenta la propria comunità, ne cura gli interessi e ne promuove lo sviluppo. 2. Il Comune si avvale della sua autonomia, nel rispetto della Costituzione e dei principi generali dell’ordinamento, per lo sviluppo della propria attività e il perseguimento dei suoi fini istituzionali. 3. Il Comune rappresenta la comunità di Favale di Malvaro nei rapporti con lo Stato, con la Regione Liguria, con la Provincia di Genova e con gli altri enti o soggetti pubblici e privati. Art. 2 – Finalità 1. Il Comune promuove lo sviluppo e il progresso civile, sociale ed economico della comunità di Favale di Malvaro, ispirandosi ai valori e agli obiettivi della Costituzione. 2. Il Comune ricerca la collaborazione e la cooperazione con altri soggetti pubblici e privati e promuove la partecipazione dei singoli cittadini, delle associazioni e delle forze sociali ed economiche all’attività amministrativa. 3. In particolare il Comune ispira la sua azione ai seguenti principi: a) rimozione di tutti gli ostacoli che impediscono l’effettivo sviluppo della persona umana e l’eguaglianza degli individui; b) promozione di una cultura di pace e cooperazione internazionale e di integrazione razziale; c) recupero, tutela e valorizzazione delle risorse naturali, ambientali, storiche, -

TIGULLIO Ambito : 2.4 - FONTANABUONA : Neirone, Moconesi, Tribogna, Favale Di Malvaro, Lorsica, Cicagna, Orero, Coreglia Ligure, San Colombano Certenoli, Carasco

PROVINCIA DI GENOVA Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento Area : 2 - TIGULLIO Ambito : 2.4 - FONTANABUONA : Neirone, Moconesi, Tribogna, Favale di Malvaro, Lorsica, Cicagna, Orero, Coreglia Ligure, San Colombano Certenoli, Carasco • Analisi : L’ambito comprende il bacino del Lavagna, la porzione terminale del bacino del T.Sturla, nonchè il bacino medio- Altri fenomeni d'instabilità in atto sono stati rilevati all’interno dei corpi di alcune paleofrane. Nell’area del bacino si alto del T.Cicana (affluente dello Sturla). trovano un gran numero di aree detritiche riferibili a corpi di paleofrana (la superficie totale di queste aree, 88 in totale, è di poco superiore al 3 % della superficie dell’intero bacino). Questi accumuli possono considerarsi in Profilo : AREE STORICAMENTE INONDATE massima parte ormai completamente stabilizzati e solo in particolari condizioni l’intero corpo di frana, o una porzione di esso, può essere considerato suscettibile di potenziale riattivazione. Sul torrente Lavagna eventi alluvionali 1948 e 1953 in località Piana di Calvari, Pian Dei Cunei , La Pozza e Rientra in questa fenomenologia la paleofrana di grandi dimensioni su cui sorge il paese di Ognio. In questo caso, Perella in comune di San Colombano Certenoli in sponda destra e sinistra, asportazione argini . per esempio, alcuni piccoli dissesti che hanno interessato manufatti dimostrano la potenziale riattivazione del A Carasco alla confluenza con lo Sturla, da Campo Martino a Terrarossa in sponda destra e sinistra. corpo di paleofrana. Un altro caso critico è quello della paleofrana in località Cassottana presso Cicagna. La instabilità del corpo Profilo : AREE INTERESSATE DA RISCHIO IDRAULICO detritico è indicata dal franamento di una porzione di pendio coltivato a fasce che ha interessato la strada comunale e invaso i piani inferiori di una abitazione privata. -

Provincia Località Zona Climatica Altitudine GENOVA ARENZANO D

Premi ctrl+f per cercare il tuo comune Provincia Località Zona climatica Altitudine GENOVA ARENZANO D 6 AVEGNO D 34 BARGAGLI E 341 BOGLIASCO D 25 BORZONASCA D 167 BUSALLA E 358 CAMOGLI D 32 CAMPO LIGURE E 342 CAMPOMORONE D 118 CARASCO D 26 CASARZA LIGURE D 34 CASELLA E 410 CASTIGLIONE CHIAVARESE E 271 CERANESI D 80 CHIAVARI D 5 CICAGNA D 88 COGOLETO D 4 COGORNO D 38 COREGLIA LIGURE E 308 CROCEFIESCHI F 742 DAVAGNA E 522 FASCIA F 900 FAVALE DI MALVARO E 300 FONTANIGORDA F 819 GENOVA D 19 GORRETO E 533 ISOLA DEL CANTONE E 298 LAVAGNA D 6 LEIVI E 272 LORSICA E 343 LUMARZO D 228 MASONE E 403 MELE D 125 MEZZANEGO D 83 MIGNANEGO D 137 MOCONESI D 132 MONEGLIA D 4 MONTEBRUNO F 655 MONTOGGIO E 438 NE D 68 NEIRONE E 342 ORERO D 169 PIEVE LIGURE D 168 PORTOFINO D 3 PROPATA F 990 RAPALLO D 2 RECCO D 5 REZZOAGLIO F 700 RONCO SCRIVIA E 334 RONDANINA F 981 ROSSIGLIONE E 297 ROVEGNO F 658 SAN COLOMBANO CERTENOLI D 45 SANTA MARGHERITA LIGURE D 13 SANTO STEFANO D'AVETO F 1012 SANT'OLCESE D 155 SAVIGNONE E 471 SERRA RICCÌ D 187 SESTRI LEVANTE D 4 SORI D 14 TIGLIETO E 500 TORRIGLIA F 769 TRIBOGNA E 279 USCIO E 361 VALBREVENNA E 533 VOBBIA E 477 ZOAGLI D 17 Provincia Località Zona climatica Altitudine IMPERIA AIROLE D 149 APRICALE D 273 AQUILA D'ARROSCIA E 495 ARMO E 578 AURIGO E 431 BADALUCCO D 179 BAJARDO F 900 BORDIGHERA C 5 BORGHETTO D'ARROSCIA D 155 BORGOMARO D 249 CAMPOROSSO C 25 CARAVONICA D 360 CARPASIO E 720 CASTEL VITTORIO E 420 CASTELLARO D 275 CERIANA D 369 CERVO C 66 CESIO E 530 CHIUSANICO D 360 CHIUSAVECCHIA D 140 CIPRESSA D 240 CIVEZZA D 225 -

Home Page BANDO HCP 2014 (Aggiornamento 22.8.2014)

Home page BANDO HCP 2014 (aggiornamento 22.8.2014) Aggiornamento casella A seguito di pubblicazione di specifico avviso pubblico dell’INPS, prevista entro settembre, gli utenti dell’INPS Gestione dipendenti pubblici, residenti nel territorio dell’ASL 4 Chiavarese potranno presentare domanda di intervento socio - assistenziale per sé, per i loro congiunti conviventi e per i loro familiari di primo grado non autosufficienti. La domanda di intervento socio-assistenziale dovrà essere trasmessa esclusivamente per via telematica attraverso il sito www.inps.it. La presentazione per via telematica, così come attraverso il contact center, richiede il possesso di un PIN on Line, da parte del soggetto richiedente che dovrà essere iscritto alla banca dati dell’INPS. In caso di particolari difficoltà il richiedente potrà presentare domanda attraverso il servizio di Contact Center al n. 803164 gratuito da numeri fissi e al n. 06 164 164 a pagamento da cellulare. Da lunedì 8 settembre saranno altresì aperti gli sportelli sociali per informazioni e supporto alla presentazione delle domande, come di seguito elencato: Rapallo P.za Molfino,10- Ex Ospedale Pian Terreno Martedì e venerdì dalle ore 10 alle13 Giovedì dalle 14,30 alle 17,30 Chiavari Via GB Ghio, 9 - c/o Distretto 15 Martedì dalle ore 9 alle 11 Mercoledì dalle ore 14 alle17 Cicagna Via Pian mercato,15 - Presidio Poliambulatoriale ASL 4 Chiavarese 2° e 4° Giovedì dalle ore 9 alle 11 E’ opportuno attivarsi per l’iscrizione in banca dati dell’Inps Gestione Dipendenti Pubblici del beneficiario o del richiedente, qualora non sia dipendente o pensionato, tramite il modulo iscrizione in banca dati scaricabile dalla sezione Moduli del sito INPS, Area dedicata alla gestione dei dipendenti pubblici e l’ acquisizione dell’attestazione ISEE presso un patronato. -

Diapositiva 1

L’AGRICOLTURA SOCIALE IN LIGURIA E FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA AREE PILOTA A CONFRONTO 1 INDICE PREMESSA LIGURIA E FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA A CONFRONTO ◦ VAL FONTANABUONA E VAL TREBBIA – GAL GENOVESE ◦ GEMONESE, CANAL DEL FERRO E VAL CANALE – GAL OPEN LEADER TERRITORIO SVILUPPO DEMOGRAFICO SITUAZIONE SOCIO ECONOMICA SERVIZI DI INTERESSE GENERALE SETTORE AGRICOLO L’AGRICOLTURA SOCIALE ◦ COS’E’ L’AGRICOLTURA SOCIALE ◦ UNIONE EUROPEA: NORMATIVA ED ESPERIENZE ◦ ITALIA: NORMATIVA ED ESPERIENZE ◦ FRIULI VENEZIA GIULIA : NORMATIVA ED ESPERIENZE ◦ LIGURIA: NORMATIVA ED ESPERIENZE BIBLIOGRAFIA 2 PREMESSA OBIETTIVI E FINALITA’ DEL PROGETTO DI COOPERAZIONE SOCIALE INTERTERRITORIALE “AGRICOLTURA SOCIALE VERSO IL DISTRETTO SOCIO RURALE” L’obiettivo generale del progetto è creare un distretto socio rurale, ovvero un sistema produttivo caratterizzato da un'identità storico/culturale e territoriale omogenea derivante dall'integrazione fra attività agricole e altre attività locali, nonché dalla produzione di beni o servizi di particolare specificità, coerenti con le tradizioni e le vocazioni naturali e territoriali. Il distretto rurale è lo strumento flessibile per valorizzare al meglio le produzioni locali e tipiche, le risorse naturali e artigianali, le attività turistiche ed imprenditoriali, creando un’immagine riconoscibile del nostro territorio. Un’importante occasione per contribuire alla tutela dell’ambiente, creare una politica industriale di sviluppo ed innovazione e sostenere una diffusa qualificazione delle risorse umane in ogni settore. 3 PREMESSA -

Direzione Sociosanitaria Dipartimento Di Cure Primarie E Attività Distrettuali S.S.D

PO/ RSA 40 MODULO DOMANDA DI INSERIMENTO IN LISTA DI M/RSA 2 ATTESA PER LE STRUTTURERESIDENZIALI/ SEMIRESIDENZIALI IN CONVENZIONE CON ASL 4 Rev. 0 SSD RSA Pag. 1 DOMANDA DI INSERIMENTO IN LISTA DI ATTESA PER LE STRUTTURE RESIDENZIALI/SEMIRESIDENZIALI IN CONVENZIONE CON ASL 4 Direzione Sociosanitaria Dipartimento di Cure Primarie e Attività Distrettuali S.S.D. RSA e Attività Geriatrica Territoriale Cognome __________________________________ Nome ________________________________ Data di nascita _________ Comune di nascita ____________________________ Provincia_______ Indirizzo _________________________________________________ Telefono _______________ Cod Fiscale___________________________________________________ La domanda è presentata dallo stesso per conto dello stesso da: Cognome _______________________ Nome________________ data di nascita ______________ Comune di nascita _____________________ Provincia _________ Indirizzo ___________________________________________________ Telefono _____________ Cod. Fiscale_____________________________________________ in qualità di: Familiare: Tutore/Amministratore di sostegno: Altro (specificare)________________ dichiara che la persona si trova presso: ________________________________________________ dichiara di indicare come scelta preferenziale MASSIMO n. 2 strutture residenziali: DISTRETTO 14 CASA LAURA S.R.L. - RAPALLO VILLA SAN FORTUNATO - RAPALLO KOS CARE MINERVA - RAPALLO VILLA CHIARA S.R.L. - RAPALLO RESIDENZAVilla Chiara TASSO - Rapallo - RAPALLO VILLA SORRISO S.R.L - RAPALLO PII ISTITUTI -

Oggetto: Approvazione Programma Stralcio D'interventi Urgenti

“AMBITO TERRITORIALE OTTIMALE DELLA PROVINCIA DI GENOVA” SERVIZIO IDRICO INTEGRATO Provincia di Genova Direzione Ambiente, Ambiti Naturali e Trasporti Segreteria Tecnica A.T.O. ESTRATTO dal processo verbale della Conferenza dei Sindaci del 9 marzo 2012 Decisione N. 1 OGGETTO: Sentenza Corte Costituzionale 335/2008 – Calcolo degli oneri deducibili ai sensi e per gli effetti di cui all’ar. 8 sexies, legge 27 febbraio 2009 n. 13 “Disposizioni in materia di servizio idrico integrato”. L’anno duemiladodici, addì 9 del mese di marzo, alle ore 9.00 in Genova, presso la Sala multimediale dei Servizi Distaccati della Provincia di Genova, Largo F. Cattanei 3, si è adunata in seduta pubblica la Conferenza degli Enti Locali convenzionati per decidere sugli argomenti iscritti all’ordine del giorno. Presiede l’Assessore alle Politiche delle Acque della Provincia di Genova, Dott. Paolo Perfigli. Fatto l’appello nominale e constatato che la conferenza dei rappresentanti degli Enti Locali convenzionati è validamente costituita, ai sensi dell’art. 8 della Convenzione di Cooperazione, essendo presente la maggioranza assoluta degli enti suddetti determinata sia in termini numerici (n. 51 Comuni /67 ) sia in termini di rappresentanza (abitanti pari al 96.81% della popolazione dell’Ambito), come risulta dalla sottostante tabella: COMUNE PRESENTE ASSENTE ARENZANO X AVEGNO X BARGAGLI X BOGLIASCO X BORZONASCA X BUSALLA X CAMOGLI X CAMPO LIGURE X CAMPOMORONE X CARASCO X CASARZA LIGURE X CASELLA X CASTIGLIONE CHIAVARESE X CERANESI X CHIAVARI X CICAGNA X COGOLETO -

Ocxxxxx Manifesto Consiglio Regionale E Presidente Regione

ELEZIONE DEL PRESIDENTE DELLA GIUNTA REGIONALE E DEL CONSIGLIO REGIONALE DELLA LIGURIA DI DOMENICA 20 E LUNEDÌ 21 SETTEMBRE 2020 CIRCOSCRIZIONE ELETTORALE PROVINCIALE DI GENOVA N. 10 CANDIDATI ALLA CARICA DI PRESIDENTE DELLA GIUNTA REGIONALE E LISTE PROVINCIALI COLLEGATE PER L’ELEZIONE DEI CONSIGLIERI CANDIDATI A PRESIDENTE DELLA GIUNTA REGIONALE CARLO FERRUCCIO MARIKA CARPI SANSA CASSIMATIS Genova 08/04/1983 Savona 09/09/1968 Monte Carlo (Monaco) 23/01/1962 LISTA PROVINCIALE N. 1 LISTA PROVINCIALE N. 2 LISTA PROVINCIALE N. 3 LISTA PROVINCIALE N. 4 LISTA PROVINCIALE N. 5 LISTA PROVINCIALE N. 6 LISTA PROVINCIALE N. 7 Gian Piero BUSCAGLIA Margherita ASQUASCIATI Sebastiano SCIORTINO Giovanni LUNARDON Giovanni Battista PASTORINO detto Gianni Andrea BOCCACCIO Marika CASSIMATIS Alessandria 11/10/1953 Genova 12/08/1968 Genova 21/03/1957 Savona 19/11/1972 Genova 26/07/1959 Genova 30/01/1970 Monte Carlo (Monaco) 23/01/1962 Cornelia MATEI Fabio BERTOLDI Bruno VITALI Luca GARIBALDI Cesira BERTONI Andrea WEISS Sergio POGGI Ploiesti (Romania) 07/08/1975 Genova 28/04/1961 Pavia 04/06/1957 Chiavari (Ge) 03/11/1982 Arenzano (Ge) 30/03/1960 Genova 22/04/1983 Genova 17/05/1968 Carlo CARPI Paula BONGIORNI Massimiliano AMANTINI Patrizia Luisa AVAGN I NA Andrea CAVA ZZ A Fabio TOSI Nadia GENTILINI Genova 08/04/1983 Sestri Levante (Ge) 26/12/1969 Santa Margherita Ligure (Ge) 03/05/1972 Genova 19/06/1954 Sestri Levante (Ge) 06/11/1970 Rapallo (Ge) 24/09/1978 Chiavari (Ge) 23/12/1963 Silvana CARACCIOLO Selena CANDIA Angelo SPANÒ Maria Luisa BIORCI detta Bobo -

10.Notiziario.Primavera.Pdf

PROGETTO DI DIDATTICA AMBIENTALE Notiziario Ufficiale del ENCICLOPEDIA DEL PARCO diché inizia la sua covata, scegliendo un LA SETTIMANA DELLA CULTURA Parco Naturale Regionale dell’Aveto momento in cui il proprietario del nido è as - UNA PASSEGGIATA Direttore Responsabile: Luca Peccerillo IL CUCULO sente per deporvi le uova, (un solo uovo in La Settimana della Cultura, promossa tette ofiolitiche partecipanti al progetto: Redazione: Paolo Cresta, Maria Sciutti È un uccello piuttosto allungato, di dimen - ogni nido), eliminando ogni volta un uovo SUL FONDO DELL’OCEANO Aut. Trib. di Chiavari N°1 - 2005 dal Ministero per i Beni e le Attività le prime medie delle scuole di e Studio grafico e impaginazione Sagep Editori S.r.l. sioni discrete (all’incirca quelle di un co - dell’ospite . In un paio di giorni depone una Primavera Culturali, quest’anno si svolgerà dal 16 Rezzoaglio, Santo Stefano d’Aveto, Ne e COPIA OMAGGIO Aprile - Giugno 2010 PARCO CERTIFICATO ISO 14001 lombo), con coda lunga arrotondata, ali ap - quindicina di uova in altrettanti nidi. al 25 aprile. Il Coordinamento Aree Protette Borzonasca si sono recate a fine aprile al - puntite e affilate, becco abbastanza lungo, a Questa particolare strategia riproduttiva La Regione Liguria, al fine di valorizza - Ofiolitiche (C.A.P.O.), costituito il 23 la Riserva Naturale Regionale Monti punta, zampe gialle con due dita in avanti e provoca frequenti casi di poliandrìa : la re la fitta proposta di eventi, mostre, giugno 2001 in occasione del Convegno Rognosi, in provincia di Arezzo, dove ad due all’indietro, che gli femmina infatti si accoppia con più di un conferenze ecc . -

Organizzazione Complessiva Delle Attrezzature E Degli Impianti Pubblici E Di Interesse Pubblico Di Scala Sovracomunale (Art

PROVINCIA DI GENOVA Piano Territoriale di Coordinamento ORGANIZZAZIONE COMPLESSIVA DELLE ATTREZZATURE E DEGLI IMPIANTI PUBBLICI E DI INTERESSE PUBBLICO DI SCALA SOVRACOMUNALE (ART. 20 - 1° COMMA, LETT. E,PUNTO 2 - DELLA L.R. 36/97) AREE/IMMOBILI PER INSEDIAMENTI SCOLASTICI DI ISTRUZIONE MEDIA SUPERIORE DA MANTENERE O DA POTENZIARE (CONF) Scheda n. A6/1 Denominazione : PLESSO SCOLASTICO DI S. COLOMBANO A) ELEMENTI IDENTIFICATIVI E DESCRITTIVI superficie dell’area : ha - consistenza edificato Volume mc 2.100 c esistente : aree libere disponibili : ha - S.L.A.: mq. 634 c. LOCALIZZAZIONE caratteristiche morfologiche : PIANEGGIANTE Comune : S. COLOMBANO CERTENOLI Area di PTC : 2 - TIGULLIO caratteristiche della proprietà : COMUNE DI S. COLOMBANO CERTENOLI Località : Ambito di PTC : 2.4 - FONTANABUONA stato di conservazione degli immobili e delle aree : BUONO Attuale ISTITUTO AGRARIO MARSANO (SEZ. STACCATA) utilizzo : dotazione di servizi e attrezzature all’interno ASSENTE dell’area : Ambito 6: Comuni di: Borzonasca, Carasco, Casarza L., Castiglione Chiavarese, Chiavari, Cicagna, Cogorno, Coreglia, Favale di Malvaro, Lavagna, Leivi, Lorsica, Lumarzo, Mezzanego, Moconesi, Moneglia, Nè, Neirone, Orero, caratteristiche dell’assetto insediativo a contorno : INSEDIAMENTI AGRICOLI Portofino, Rapallo, Rezzoaglio, S. Colombano Certenoli, S. Margherita L., S. Stefano D’Aveto, Sestri L., Tribogna, condizione di accessibilità veicolare : BUONA Zoagli livello di servizio di trasporto pubblico : SUFFICIENTE RIFERIMENTI ALLA PROGRAMMAZIONE SCOLASTICA (ex L. 23/96 e D.P.R. 233/98) : ISTITUTO SOTTODIMENSIONATO AUTONOMIA IN DEROGA PER UNICITA’ DI INDIRIZZO AMBITO 6 DATI all’1.1.1998 SCHEDA A6/1 – CONSISTENZA sez. staccata Marsano POP.RES. (Circ.) = 145.853 AVVIATA A.S. 1999/2000 POP. RES. fascia d’età (14-18) = 5.269 a.s.97/98: classi -, iscr. -

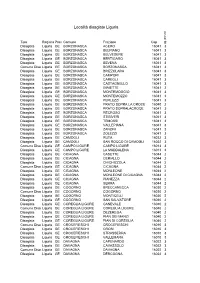

Località Disagiate Liguria

Località disagiate Liguria Tipo Regione Prov. Comune Frazione Cap gg. previsti Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA ACERO 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA BELPIANO 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA BELVEDERE 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA BERTIGARO 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA BEVENA 16041 3 Comune DisagiataLiguria GE BORZONASCA BORZONASCA 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA BRIZZOLARA 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA CAMPORI 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA CAREGLI 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA CASTAGNELLO 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA GIAIETTE 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA MONTEMOGGIO 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA MONTEMOZZO 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA PERLEZZI 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA PRATO SOPRA LA CROCE 16040 2 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA PRATO SOPRALACROCE 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA RECROSO 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA STIBIVERI 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA TEMOSSI 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA VALLEPIANA 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA ZANONI 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE BORZONASCA ZOLEZZI 16041 3 Disagiata Liguria GE CAMOGLI RUTA 16032 3 Disagiata Liguria GE CAMOGLI SAN ROCCO DI CAMOGLI 16032 3 Comune DisagiataLiguria GE CAMPO LIGURE CAMPO LIGURE 16013 3 Disagiata Liguria GE CAMPO LIGURE LA MADDALENA 16013 3 Disagiata Liguria GE CICAGNA CASETTE 16044 2 Disagiata Liguria GE CICAGNA CERIALLO 16044 2 Disagiata Liguria GE CICAGNA CHICHIZZOLA 16044 2 Comune DisagiataLiguria -

Rankings Municipality of Favale Di Malvaro

10/1/2021 Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population Demographic balance, population and familiy trends, age classes and average age, civil status and foreigners Skip Navigation Links ITALIA / Liguria / Province of Genova / Favale di Malvaro Powered by Page 1 L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Adminstat logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH ITALIA Municipalities Powered by Page 2 Arenzano Stroll up beside >> L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Fontanigorda AdminstatAvegno logo DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH Genova Bargagli ITALIA Gorreto Bogliasco Isola del Borzonasca Cantone Busalla Lavagna Camogli Leivi Campo Ligure Lorsica Campomorone Lumarzo Carasco Masone Casarza Ligure Mele Casella Mezzanego Castiglione Mignanego Chiavarese Moconesi Ceranesi Moneglia Chiavari Montebruno Cicagna Montoggio Cogoleto Ne Cogorno Neirone Coreglia Ligure Orero Crocefieschi Pieve Ligure Davagna Portofino Fascia Propata Favale di Malvaro Rapallo Recco Rezzoaglio Ronco Scrivia Rondanina Rossiglione Rovegno San Colombano Certenoli Sant'Olcese Santa Margherita Powered by Page 3 Ligure L'azienda Contatti Login Urbistat on Linkedin Santo Stefano Provinces Adminstat logo d'Aveto DEMOGRAPHY ECONOMY RANKINGS SEARCH GENOVAITALIA Savignone IMPERIA Serra Riccò LA SPEZIA Sestri Levante SAVONA Sori Tiglieto Torriglia Tribogna Uscio Valbrevenna Vobbia Zoagli Regions Abruzzo Liguria Basilicata Lombardia Calabria Marche Campania Molise Città del Piemonte Vaticano Puglia Emilia-Romagna Repubblica di Friuli-Venezia San Marino Giulia