US-Pakistan Counter-Terrorism Cooperation: Dynamics and Challenges Shanthie D’Souza Abstract Pakistan Is a Frontline Ally of the US in Its Global War on Terrorism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern

SOCIOLINGUISTIC SURVEY OF NORTHERN PAKISTAN VOLUME 4 PASHTO, WANECI, ORMURI Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 1 Languages of Kohistan Volume 2 Languages of Northern Areas Volume 3 Hindko and Gujari Volume 4 Pashto, Waneci, Ormuri Volume 5 Languages of Chitral Series Editor Clare F. O’Leary, Ph.D. Sociolinguistic Survey of Northern Pakistan Volume 4 Pashto Waneci Ormuri Daniel G. Hallberg National Institute of Summer Institute Pakistani Studies of Quaid-i-Azam University Linguistics Copyright © 1992 NIPS and SIL Published by National Institute of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan and Summer Institute of Linguistics, West Eurasia Office Horsleys Green, High Wycombe, BUCKS HP14 3XL United Kingdom First published 1992 Reprinted 2004 ISBN 969-8023-14-3 Price, this volume: Rs.300/- Price, 5-volume set: Rs.1500/- To obtain copies of these volumes within Pakistan, contact: National Institute of Pakistan Studies Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: 92-51-2230791 Fax: 92-51-2230960 To obtain copies of these volumes outside of Pakistan, contact: International Academic Bookstore 7500 West Camp Wisdom Road Dallas, TX 75236, USA Phone: 1-972-708-7404 Fax: 1-972-708-7433 Internet: http://www.sil.org Email: [email protected] REFORMATTING FOR REPRINT BY R. CANDLIN. CONTENTS Preface.............................................................................................................vii Maps................................................................................................................ -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 34, Number 37, September

Executive Intelligence Review EIRSeptember 21, 2007 Vol. 34 No. 37 www.larouchepub.com $10.00 Schiller Institute: Eurasian Land-Bridge Is a Reality Bailout of Bankrupt Funds Bars Mortgage Crisis Fix LaRouche Celebrates ‘This New Millennium of Ours!’ Financiers Are ‘Up to Their Eyeballs in Caymans’ Founder and Contributing Editor: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. Editorial Board: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., Muriel Mirak-Weissbach, Antony Papert, Gerald Rose, Dennis Small, Edward Spannaus, Nancy EI R Spannaus, Jeffrey Steinberg, William Wertz Editor: Nancy Spannaus Managing Editor: Susan Welsh Assistant Managing Editor: Bonnie James Science Editor: Marjorie Mazel Hecht From the Managing Editor Technology Editor: Marsha Freeman Book Editor: Katherine Notley Photo Editor: Stuart Lewis Circulation Manager: Stanley Ezrol Who’s the guy on our cover? Some among our readers who are in INTELLIGENCE DIRECTORS need of new eyeglasses, may mistake him for Alan Greenspan—and Counterintelligence: Jeffrey Steinberg, Michele they wouldn’t be too far wrong. But this cayman is actually the CEO of Steinberg Economics: Marcia Merry Baker, Paul Gallagher a hedge fund in Queen Elizabeth’s Caribbean financial center, the Cay- History: Anton Chaitkin Ibero-America: Dennis Small man Islands. See John Hoefle’s chronicle (p. 15) for the gory details. Law: Edward Spannaus Our Feature documents how the U.S. home mortgage crisis is spin- Russia and Eastern Europe: Rachel Douglas ning so far out of control, that it threatens to bring down the global fi- United States: Debra Freeman nancial system any day—and yet, the U.S. Congress refuses to act. INTERNATIONAL BUREAUS With the Executive branch hijacked by Anglo-Dutch Liberalism, there Bogotá: Javier Almario Berlin: Rainer Apel is no other branch of government that can initiate effective action at this Copenhagen: Poul Rasmussen time. -

Geology of the Southern Gandghar Range and Kherimar Hills, Northern Pakistan

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Michael D. Hylland for the degree of Master of Science in Geology presented on May 3. 1990 Title: Geology of the Southern Gandghar Range and Kherimar Hills. Northern Pakistan Abstract approved: RobeS. Yeats The Gandghar Range and Kherimar Hills, located in the Hill Ranges of northern Pakistan, contain rocks that are transitional between unmetarnorphosed foreland-basin strata to the south and high-grade metamorphic and plutonic rocks to the north. The southern Gandghar Range is composed of a succession of marine strata of probable Proterozoic age, consisting of a thick basal argillaceous sequence (Manki Formation) overlain by algal limestone and shale (Shahkot, Utch Khattak, and Shekhai formations). These strata are intruded by diabase dikes and sills that may correlate with the Panjal Volcanics. Southern Gandghar Range strata occur in two structural blocks juxtaposed along the Baghdarra fault. The hanging wall consists entirely of isoclinally-folded Manki Formation, whereas the footwall consists of the complete Manki-Shekhai succession which has been deformed into tight, northeast-plunging, generally southeast (foreland) verging disharmonic folds. Phyllite near the Baghdarra fault displays kink bands, a poorly-developed S-C fabric, and asymmetric deformation of foliation around garnet porphyroblasts. These features are consistent with conditions of dextral shear, indicating reverse-slip displacement along the fault. South of the Gandghar Range, the Panjal fault brings the Gandghar Range succession over the Kherimar Hills succession, which is composed of a basal Precambrian arenaceous sequence (Hazara Formation) unconformably overlain by Jurassic limestone (Samana Suk Formation) which in turn is unconformably overlain by Paleogene marine strata (Lockhart Limestone and Patala Formation). -

Modes of Iraqi Resistance to American Occupation

Modes of Iraqi Resistance to American Occupation Jeremy Pressman University of Connecticut Department of Political Science 2005-4 About the Matthew B. Ridgway Center The Matthew B. Ridgway Center for International Security Studies at the University of Pittsburgh is dedicated to producing original and impartial analysis that informs policymakers who must confront diverse challenges to international and human security. Center programs address a range of security concerns—from the spread of terrorism and technologies of mass destruction to genocide, failed states, and the abuse of human rights in repressive regimes. The Ridgway Center is affiliated with the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) and the University Center for International Studies (UCIS), both at the University of Pittsburgh. This working paper is one of several outcomes of the Ridgway Working Group on Challenges to U.S. Foreign and Military Policy chaired by Davis B. Bobrow. Modes of Iraqi Resistance to American Occupation Jeremy Pressman, University of Connecticut Department of Political Science The United States invaded Iraq in March 2003 with a clear vision for Iraq’s future. In moving to topple Saddam Hussein, Washington foresaw the development of a stable, democratic, friendly, and non-threatening Iraq. Resistance to U.S. preferences, however, developed from day one and over time the United States was forced to modify its policies and lower its expectations. Political and military, not to mention violent, opposition to U.S. and allied officials revealed the problematic U.S. assumptions going into the war and led to repeated changes in US policy. In addition to the direct human, financial, and political costs, the long term implications of Iraqi resistance are significant. -

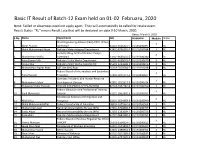

Basic IT Result of Batch 12

Basic IT Result of Batch-12 Exam held on 01-02 Februaru, 2020 Note: Failled or absentees need not apply again. They will automatically be called for retake exam. Result Status "RL" means Result Late that will be declared on date 9-10 March, 2020. Dated: March 5, 2020 S.No Name Department NIC Studentid Module Status Chief Engineering Adviser (CEA) /CFFC Office, 3 1 Abrar Hussain Islamabad 61101-5666325-7 VU191200097 RL 2 Malik Muhammad Ahsan Pakistan Meteorological Department 42401-8756355-7 VU191200184 3 RL Forestry Wing, M/O of Climate Change, 3 3 Muhammad Shafiq Islamabad 13101-3645024-5 VU191200280 RL 4 Asim Zaman Virk Pakistan Public Works Department 61101-4055043-7 VU191200670 3 RL 5 Rasool Bux Pakistan Public Works Department 45302-1434648-1 VU191200876 3 RL 6 Muhammad Asghar Khan S&T Dte GHQ Rwp 55103-7820568-7 VU191201018 3 RL Federal Board of Intermediate and Secondary 3 7 Tariq Hussain Education 37405-0231137-3 VU191200627 RL Overseas Pakistanis and Human Resource 3 8 Muhammad Zubair Development Division 42301-0211817-3 VU191200624 RL 9 Khaawaja Shabir Hussain CCD-VIII PAK PWD G-9/1 ISLAMABAD 82103-1652182-9 VU191200700 3 RL Federal Education and Professional Training 3 10 Sajid Mehmood Division 61101-1862402-9 VU191200933 RL Directorate General of Immigration and 3 11 Allah Ditta Passports 61101-6624393-9 VU191200040 RL 12 Malik Muhammad Afzal Federal Directorate of Education 38302-1075962-9 VU191200509 3 RL 13 Muhammad Asad National Accountability Bureau (KPk) 17301-6704686-5 VU191200757 3 RL 14 Sadiq Akbar National Accountability -

Valid License Holders (Industrial Facilities) Sr

Valid License Holders (Industrial Facilities) Sr. Facility Attock 1 Fauji Cement Company Limited, Near Village Jhang, Tehsil Fateh Jhang, Attock 2 Pakistan Aeronautical Complex Board, (PACB), Kamra, Attock Chakwal 1 Best Way Cement Ltd., Choie Mallot Road, Kalar Kahar, Chakwal 2 DG KHAN Cement Co. Ltd., P. O. Khairpur, Kallar Kahar, Choa Saiden Shah Road, Chakwal 3 Best Way Cement Ltd., 22 Km, Kallar Kahar Choa Road, Chakwal Dera Ghazi Khan 1 D.G. Khan Cement Company Ltd., Khofli Sattai, Dera Ghazi Khan Faisalabad 1 Ibrahim Fibres Ltd., Ibrahim Centre, 15-Club Road, Faisalabad 2 Nuclear Institute for Agriculture & Biology (NIAB), P.O. Box No. 128, Jhang Road, Faisalabad, Faisalabad 3 Masood Textile Mills Ltd., 32-km Sheikhupura Road, Faisalabad, Faisalabad 4 Five Star Foods (Gourmet), 8.5 km, Chak No. 104/R.B, Jaranwala Road, Khurrianwala, Distt. Faisalabad, Faisalabad 5 Coca Cola Beverages Pakistan Limited, Faisalabad Green Field, Plot 52-60, M3 Industrial City, Sahianwala Interchange, Faisalabad 6 Mehran Bottlers (Pvt.) Ltd., Plot No. 29/A, Phase 1A, M-3 Industrial City, Sahianwala, Faisalabad Ghotki 1 Engro Fertilizer Limited, Daharki, Ghotki 2 ICS Pakistan (Pvt.) Ltd., G. T. Road Daharki, Ghotki 3 Fauji Fertilizer Company Limited, Mirpur Mathelo-65050, Ghotki Gujranwala 1 Tayyaba Industries International, 18-B/C, Trust Plaza, G.T. Road, Gujranwala 2 Coca Cola Beverages Pakistan Ltd., Khiali By-Pass Road, Gujranwala 3 PAK PIPE Steel Industries, G.T Road, Gujranwala 4 NauBahar Bottling Company (Pvt.) Ltd., 38-40/A Small Industrial Estate, Gujranwala 5 Apple Layers (Pvt) Ltd., 18km, G.T Road, Kamoke, Gujranwala Haripur 1 Tri-Pack Films Ltd., Phase IV Industrial Estate, Haripur 2 Bestway Cement Limited, Suraj Gali Road, Haripur 3 Bestway Cement Limited, Farooqia 12 K.M Taxila-Haripur Road, Haripur 4 Horizon Paper & Board Mills (Pvt.) Ltd., Plot No. -

Foialog FY07.Pdf

Request ID Requester Name Organization Received Date Closed Date Request Description 07-F-0001 Connolly, Ward - 10/2/2006 10/2/2006 All records regarding the service of the 208th Engineer Combat Battalion anytime between December 7, 1941 and January 1, 1947. 07-F-0002 Slocum, Phillip - 10/2/2006 10/2/2006 Information relating to an operation at the end of the Gulf War in April of 1991 dubbed "Operation Manly Rip". 07-F-0004 Skelley, Lynne Federal Sources, 10/2/2006 - A clearly releasable copy of Sections A through J of the awarded contract, including Inc. the statement of work, for the contract awarded from solicitation number HROO11O6ROO2. 07-F-0005 Skelley, Lynne Federal Sources, 10/2/2006 10/3/2006 A copy of Section A (the cover page) for any contract awarded to date from Inc. solicitation number EFTHQ00038615002. 07-F-0006 Skelley, Lynne Federal Sources, 10/2/2006 6/29/2007 A copy of Section A (the cover page) for any contract awarded to date from Inc. solicitation number BAA0539. 07-F-0007 Skelley, Lynne Federal Sources, 10/2/2006 1/10/2007 A clearly releasable copy of Section A (the cover page) of any contract awarded to Inc. date off of solicitation number BAAO6O6. 07-F-0008 Battle, Joyce The National 10/2/2006 - All documents from March 1 through December 31, 2003 concerned with Security Archive discussions with the United Kingdom regarding 1) the establishment of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq; and 2) the legal status of the CPA. 07-F-0009 Kurtzman, Daniel Law Offices of 10/2/2006 10/11/2006 Requesting: 1. -

Pakistans Inter-Services Intelligence

Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite EINFÜHRUNG 1 Pakistans Inter-Services Intelligence 1 DAS ERSTE JAHRZEHNT 8 1.1 Die Gründungsgeschichte 8 1.2 Gründungsvater Generalmajor Walter J. Cawthorne 9 1.3 Die ISI-Führung der ersten Jahre 11 1.4 Strukturelle Konzepte: 1948-1958 11 2 DIE ZEIT DER ERSTEN GENERÄLE: 1958-1971 14 2.1 Der ISI unter Feldmarschall Ayub Khan (1958-1969) 14 2.2 General Yahya Khan (1969-1971) 20 2.3 Veränderungen in der ISI-Leitungs- und Aufgabenstruktur 23 2.4 ISI und CIA - verstärkte Kooperationen 24 2.5 Operationen in Indien: Die 60er und 70er Jahre 3 REGIERUNGSCHEF ZULFIKAR ALI BHUTTO: 1971-1977 28 3.1 Cherat – Kampfschule der Armee 28 3.2 Brennpunkt Balochistan: Die 70er Jahre 29 3.3 Die Geburt des Special Operation Bureau 3.4 Eine fatale Ernennung: Armeechef Zia-ul-Haq 32 3.5 Innenpolitische Verstrickungen 34 3.6 Der Sturz eines Regierungschefs 37 4 ZWISCHENBILANZ VON 30 JAHREN: 1948-1977 40 5 DER ISI UNTER ZIA-UL-HAQ: 1977-1988 5.1 Die ausgehenden 70er Jahre 44 5.2 Weihnachten 1979: Die Afghanistan-Option 46 5.3 Das Afghanistan-Bureau im ISI 49 5.4 Logistik und Korruption 53 5.5 Ingenieur Gulbuddin Hekmatyar 57 5.6 Das Jahr 1987: Abschied von Akhtar Rehman und Yousaf 58 6 TURBULENZEN ENDE DER ACHTZIGER JAHRE 62 6.1 Von Akhtar Rehman zu Hamid Gul 62 6.2 Die Katastrophe im Ojhri-Camp 63 6.3 Ein Flugzeugabsturz mit Folgen: Der Tod von Zia-ul-Haq 65 6.4 Desaster in Afghanistan: Jalalabad 69 7 INNENPOLITISCH SZENARIEN: 1988-1991 73 7.1 Armeechef General Mirza Aslam Beg 73 7.2 Wahlen und Regierungsbildung 76 7.3 Im ISI: Von Hamid -

Climate Change Profile of Pakistan

Climate Change Profi le of Pakistan Catastrophic fl oods, droughts, and cyclones have plagued Pakistan in recent years. The fl ood killed , people and caused around billion in damage. The Karachi heat wave led to the death of more than , people. Climate change-related natural hazards may increase in frequency and severity in the coming decades. Climatic changes are expected to have wide-ranging impacts on Pakistan, a ecting agricultural productivity, water availability, and increased frequency of extreme climatic events. Addressing these risks requires climate change to be mainstreamed into national strategy and policy. This publication provides a comprehensive overview of climate change science and policy in Pakistan. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacifi c region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to a large share of the world’s poor. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by members, including from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. CLIMATE CHANGE PROFILE OF PAKISTAN ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org Prepared by: Qamar Uz Zaman Chaudhry, International Climate Technology Expert ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2017 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Defence Services Audit Year 2014-15

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF DEFENCE SERVICES AUDIT YEAR 2014-15 AUDITOR-GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS iii PREFACE v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY vi AUDIT STATISTICS CHAPTER-1 Ministry of Defence Production 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Status of Compliance of PAC Directives 1 AUDIT PARAS 1.3 Recoverable / Overpayments 3 1.4 Loss to State 26 1.5 Un-authorized Expenditure 29 1.6 Mis-procurement of Stores / Mis-management of contract 33 1.7 Non-Production of Records 45 CHAPTER-2 Ministry of Defence 2.1 Introduction48 2.2 Status of Compliance of PAC Directives 48 AUDIT PARAS Pakistan Army 2.3 Recoverable / Overpayments 50 2.4 Loss to State 63 2.5 Un-authorized Expenditure 67 2.6 Mis-procurement of Stores / Mis-management of Contract 84 i 2.7 Non-Production of Auditable Records 95 Military Lands and Cantonments 2.8 Recoverable / Overpayments 100 2.9 Loss to State 135 2.10 Un-authorized Expenditure 152 Pakistan Air Force 2.11 Recoverable / Overpayments 156 2.12 Loss to State 171 2.13 Un-authorized Expenditure 173 2.14 Mis-procurement of Stores / Mis-management of contract 181 Pakistan Navy 2.15 Recoverable / Overpayments 184 2.16 Loss to State 197 2.17 Un-authorized Expenditure 198 2.18 Mis-procurement of Stores / Mis-management of contract 207 Military Accountant General 2.19 Recoverable / Overpayments 215 2.20 Un-authorized Expenditure 219 Inter Services Organization (ISO’s) 2.21 Recoverable / Overpayments 222 Annexure-I MFDAC Paras (DGADS North) Annexure-II MFDAC Paras (DGADS South) ii ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS -

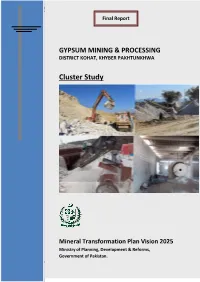

Gypsum Mining & Processing District Kohat, Khyber

Cluster Study –Gypsum Mining & Processing- Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Final Report GYPSUM MINING & PROCESSING DISTRICT KOHAT, KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA Cluster Study Mineral Transformation Plan Vision 2025 Ministry of Planning, Development & Reforms, Government of Pakistan. Cluster Based Mineral Transformation Plan V2025- Feasibility Study Page | 1 Cluster Study –Gypsum Mining & Processing- Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Contents 1. ABOUT THE STUDY.................................................................................................................................. 7 2. DESCRIPTION OF THE CLUSTER ......................................................................................................... 8 2.1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1.1. Strategic Location of the Cluster ........................................................................................ 8 2.2. Situational Analysis ....................................................................................................................... 10 2.2.1. Enterprise Base...................................................................................................................... 10 2.2.2. Products ................................................................................................................................... 16 2.2.3. Production Statistics ........................................................................................................... -

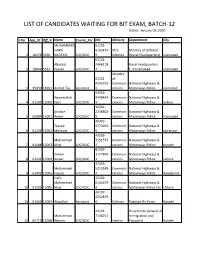

LIST of CANDIDATES WAITING for BIT EXAM, BATCH-12 Dated: January 09, 2020

LIST OF CANDIDATES WAITING FOR BIT EXAM, BATCH-12 Dated: January 09, 2020 S.No App_ID Off_Sr Name Course_For NIC Ministry Department City MUHAMMAD 61101- HARIS 0153437- M/o Ministry of Defence 1 18178 5290 NADEEM LDC/UDC 9 Defence (Naval Headquarters) Islamabad 61101- Abaid ul 2466178- Naval headquarters 2 18844 5532 hassan LDC/UDC 7 E_9 Islamabad Islamabad Ministry 61101- of 0545920- Communi National Highways & 3 35950 14991 Arshad Taj Assistant 3 cations Motorways Police Isamabad 43303- Najeebullah 9448464- Communi National Highways & 4 61209 15000 Qazi LDC/UDC 3 cations Motorways Police Sukkur 16202- Attique 2236802- Communi National Highways & 5 60984 15001 Anwar LDC/UDC 9 cations Motorways Police Islamabad 36303- Tayyab 0773203- Communi National Highways & 6 61206 15002 Mansoor LDC/UDC 5 cations Motorways Police Jarranwal 43203- Muhammad 7151573- Communi National Highways & 7 61188 15003 Afzal LDC/UDC 1 cations Motorways Police karachi 82303- Zaheer 1177840- Communi National Highways & 8 61201 15004 Anwar LDC/UDC 1 cations Motorways Police Lahore 37405- Muhammad 5210589- Communi National Highways & 9 61092 15005 Fayyaz LDC/UDC 7 cations Motorways Police Rawalpindi Hafiz 35202- Muhammad 6144679- Communi National Highways & 10 61193 15006 Nisar LDC/UDC 9 cations Motorways Police Lhr Lahore 44107- 2252879- 11 61363 15007 Attaullah Assistant 9 Defence Pakistan Air Force Karachi 42101- Directorate General of Muhammad 7146251- Immigration and 12 60719 15008 Naeem LDC/UDC 5 Interior Passports Karachi S.No App_ID Off_Sr Name Course_For NIC