The Palestinian Shahid and the Development of the Model 21St Century Islamic Terrorist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pragmatic Dimension of the Palestinian Hamas: a Network Perspective

Mishal 569 The Pragmatic Dimension of the Palestinian Hamas: A Network Perspective SHAUL MISHAL n the wake of the 11 September attack on the World Trade Center in INew York and President Bush’s “war on terrorism,” it is important to try to understand the cultural, political, and social dimensions of such radical Islamic groups as the Palestinian Hamas. Within political and academic circles in the Western world, it is common to portray Islamic movements in categorical terms that utilize binary classifications that mark real or imaginary social attributes rather than relational patterns.1 Much of this perception derives from the violence accompanying Islamic reli- gious fervor and the fanaticism marking some of its groups and regimes, raising fears of “a clash of civilizations” and “a threat” to Western liberal democratic values and social order.2 Hamas, an abbreviation of Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya (Is- lamic Resistance Movement), did not escape the binary perception, and has been described solely as a movement identified with Islamic funda- mentalism and suicide bombings. The objectives at the top of its agenda are the liberation of Palestine through a holy war (jihad) against Israel, establishing an Islamic state on its soil, and reforming society in the spirit of true Islam. It is this Islamic vision, combined with its nationalist claims and militancy toward Israel, that accounts for the prevailing image of Hamas as a rigid movement, ready to pursue its goals at any cost, with no limits or constraints. Islamic and national zeal, bitter opposition to the SHAUL MISHAL teaches at the Department of Political Science at Tel Aviv University, where his research focuses on Arab and Palestinian politics. -

The Changing Forms of Incitement to Terror and Violence

THE CHANGING FORMS OF INCITEMENT TO TERROR AND VIOLENCE: TERROR AND TO THE CHANGING FORMS OF INCITEMENT The most neglected yet critical component of international terror is the element of incitement. Incitement is the medium through which the ideology of terror actually materializes into the act of terror itself. But if indeed incitement is so obviously and clearly a central component of terrorism, the question remains: why does the international community in general, and international law in particular, not posit a crime of incitement to terror? Is there no clear dividing line between incitement to terror and the fundamental right to freedom of speech? With such questions in mind, the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs and the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung held an international conference on incitement. This volume presents the insights of the experts who took part, along with a Draft International Convention to Combat Incitement to Terror and Violence that is intended for presentation to the Secretary-General of the United Nations. The Need for a New International Response International a New for Need The THE CHANGING FORMS OF INCITEMENT TO TERROR AND VIOLENCE: The Need for a New International Response Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs המרכז הירושלמי לענייני ציבור ומדינה )ע"ר( THE CHANGING FORMS OF INCITEMENT TO TERROR AND VIOLENCE: The Need for a New International Response Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs המרכז הירושלמי לענייני ציבור ומדינה )ע"ר( This volume is based on a conference on “Incitement to Terror and Violence: New Challenges, New Responses” under the auspices of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs and the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, held on November 8, 2011, at the David Citadel Hotel, Jerusalem. -

OBITUARIES Picked up at a Comer in New York City

SUMMER 2004 - THE AVI NEWSLETTER OBITUARIES picked up at a comer in New York City. gev until his jeep was blown up on a land He was then taken to a camp in upper New mine and his injuries forced him to return York State for training. home one week before the final truce. He returned with a personal letter nom Lou After the training, he sailed to Harris to Teddy Kollek commending him Marseilles and was put into a DP camp on his service. and told to pretend to be mute-since he spoke no language other than English. Back in Brooklyn Al worked While there he helped equip the Italian several jobs until he decided to move to fishing boat that was to take them to Is- Texas in 1953. Before going there he took rael. They left in the dead of night from Le time for a vacation in Miami Beach. This Havre with 150 DPs and a small crew. The latter decision was to determine the rest of passengers were carried on shelves, just his life. It was in Miami Beach that he met as we many years later saw reproduced in his wife--to-be, Betty. After a whirlwind the Museum of Clandestine Immigration courtship they were married and decided in Haifa. Al was the cook. On the way out to raise their family in Miami. He went the boat hit something that caused a hole into the uniform rental business, eventu- Al Wank, in the ship which necessitated bailing wa- ally owning his own business, BonMark Israel Navy and Palmach ter the entire trip. -

Hamas and Fateh Neck and Neck As Palestinian Elections Near

OPINION OFFICE OF ANALYSIS RESEARCH DEPARTMENT OF STATE, WASHINGTON, DC 20520 January 19, 2005 M-05-06 Hamas and Fateh Neck and Neck As Palestinian Elections Near A just-completed Office of Research survey in the Palestinian Territories shows a much closer race at the polls than some have predicted. Among likely voters, 32 percent intend to back Fateh on the National Ballot, while 30 percent say they will support Hamas. Corruption is the leading issue among the Palestinian public, with most believing that Hamas is more qualified than Fateh to clean it up. While Hamas is seen as less able than Fateh to advance negotiations with Israel, a majority of both Fateh and Hamas supporters back a continuation of the ceasefire, ongoing talks with Israel, and a two-state solution. The survey, conducted January 13-15, indicates that eight-in-ten among the electorate are either “very likely” (53%) or “somewhat likely” (28%) to vote on the National Ballot in the January 25th elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council. Among likely voters, about a third each intend to vote for Hamas and Fateh (Table 1). Independent Palestine, led by Mustafa Bhargouti, is backed by 13 percent of likely voters. Based on these results, Fateh would gain roughly 24 of the 66 National Ballot seats, Hamas 22 seats, Independent Palestine 9 seats, with the remaining 11 split among smaller parties. These results show a closer race than other published surveys of likely voters, which have tended to place Fateh ahead at the polls by a wider margin (Appendix, Table 1). -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine

Towards Decolonial Futures: New Media, Digital Infrastructures, and Imagined Geographies of Palestine by Meryem Kamil A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (American Culture) in The University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Evelyn Alsultany, Co-Chair Professor Lisa Nakamura, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Anna Watkins Fisher Professor Nadine Naber, University of Illinois, Chicago Meryem Kamil [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2355-2839 © Meryem Kamil 2019 Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been completed without the support and guidance of many, particularly my family and Kajol. The staff at the American Culture Department at the University of Michigan have also worked tirelessly to make sure I was funded, healthy, and happy, particularly Mary Freiman, Judith Gray, Marlene Moore, and Tammy Zill. My committee members Evelyn Alsultany, Anna Watkins Fisher, Nadine Naber, and Lisa Nakamura have provided the gentle but firm push to complete this project and succeed in academia while demonstrating a commitment to justice outside of the ivory tower. Various additional faculty have also provided kind words and care, including Charlotte Karem Albrecht, Irina Aristarkhova, Steph Berrey, William Calvo-Quiros, Amy Sara Carroll, Maria Cotera, Matthew Countryman, Manan Desai, Colin Gunckel, Silvia Lindtner, Richard Meisler, Victor Mendoza, Dahlia Petrus, and Matthew Stiffler. My cohort of Dominic Garzonio, Joseph Gaudet, Peggy Lee, Michael -

The Origins of Hamas: Militant Legacy Or Israeli Tool?

THE ORIGINS OF HAMAS: MILITANT LEGACY OR ISRAELI TOOL? JEAN-PIERRE FILIU Since its creation in 1987, Hamas has been at the forefront of armed resistance in the occupied Palestinian territories. While the move- ment itself claims an unbroken militancy in Palestine dating back to 1935, others credit post-1967 maneuvers of Israeli Intelligence for its establishment. This article, in assessing these opposing nar- ratives and offering its own interpretation, delves into the historical foundations of Hamas starting with the establishment in 1946 of the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood (the mother organization) and ending with its emergence as a distinct entity at the outbreak of the !rst intifada. Particular emphasis is given to the Brotherhood’s pre-1987 record of militancy in the Strip, and on the complicated and intertwining relationship between the Brotherhood and Fatah. HAMAS,1 FOUNDED IN the Gaza Strip in December 1987, has been the sub- ject of numerous studies, articles, and analyses,2 particularly since its victory in the Palestinian legislative elections of January 2006 and its takeover of Gaza in June 2007. Yet despite this, little academic atten- tion has been paid to the historical foundations of the movement, which grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Gaza branch established in 1946. Meanwhile, two contradictory interpretations of the movement’s origins are in wide circulation. The !rst portrays Hamas as heir to a militant lineage, rigorously inde- pendent of all Arab regimes, including Egypt, and harking back to ‘Izz al-Din al-Qassam,3 a Syrian cleric killed in 1935 while !ghting the British in Palestine. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

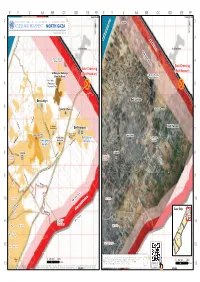

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: the Most Important Events Yasser

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: The Most Important Events Yasser Arafat Foundation 1 Early 20th Century - The total population of Palestine is estimated at 600,000, including approximately 36,000 of the Jewish faith, most of whom immigrated to Palestine for purely religious reasons, the remainder Muslims and Christians, all living and praying side by side. 1901 - The Zionist Organization (later called the World Zionist Organization [WZO]) founded during the First Zionist Congress held in Basel Switzerland in 1897, establishes the “Jewish National Fund” for the purpose of purchasing land in Palestine. 1902 - Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II agrees to receives Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement and, despite Herzl’s offer to pay off the debt of the Empire, decisively rejects the idea of Zionist settlement in Palestine. - A majority of the delegates at The Fifth Zionist Congress view with favor the British offer to allocate part of the lands of Uganda for the settlement of Jews. However, the offer was rejected the following year. 2 1904 - A wave of Jewish immigrants, mainly from Russia and Poland, begins to arrive in Palestine, settling in agricultural areas. 1909 Jewish immigrants establish the city of “Tel Aviv” on the outskirts of Jaffa. 1914 - The First World War begins. - - The Jewish population in Palestine grows to 59,000, of a total population of 657,000. 1915- 1916 - In correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, and Sharif Hussein of Mecca, wherein Hussein demands the “independence of the Arab States”, specifying the boundaries of the territories within the Ottoman rule at the time, which clearly includes Palestine. -

Israel: Leadership & Critical Decisions

The 30th Annual Conference of the Association for Israel Studies June 23–25, 2014 Israel: Leadership & Critical Decisions The Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel & Zionism Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Sede-Boqer Campus The 30th Annual Conference of the Association for Israel Studies June 23–25, 2014 Israel: Leadership & Critical Decisions The Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel & Zionism Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Sede-Boqer Campus BEN-GURION UNIVERSITY OF THE NEGEV CONFERENCE SPONSORS Ben-Gurion University of the Negev is one of Israel’s leading research universities and among the world leaders in many fields. It has approximately 20,000 students and 4,000 faculty members in the Faculties of Engineering Sciences; Health Sciences; Natural Sciences; the Pinchas Sapir Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences; the Guilford Glazer Faculty of Business and Management; the Joyce and Irving Goldman School of Medicine; the Kreitman School of Advanced Graduate Studies; the Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies and the Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel and Zionism's, Israel Studies Program. More than 100,000 alumni play important roles in all areas of research and development, industry, health care, the economy, society, culture and education in Israel. The University has three main campuses: The Marcus Family Campus in Beer- Sheva; the research campus at Sede Boqer and the Eilat Campus, and is home to national and multi-disciplinary research institutes: the National Institute for Biotechnology in the Negev; the National Institute of Solar Energy; the Ilse Katz Institute for Nanoscale Science and Technology; the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research; the Ben-Gurion Research Institute for the Study of Israel & Zionism, and Heksherim - The Research Institute for Jewish and Israeli Literature and Culture. -

Executive Intelligence Review, Volume 34, Number 37, September

Executive Intelligence Review EIRSeptember 21, 2007 Vol. 34 No. 37 www.larouchepub.com $10.00 Schiller Institute: Eurasian Land-Bridge Is a Reality Bailout of Bankrupt Funds Bars Mortgage Crisis Fix LaRouche Celebrates ‘This New Millennium of Ours!’ Financiers Are ‘Up to Their Eyeballs in Caymans’ Founder and Contributing Editor: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr. Editorial Board: Lyndon H. LaRouche, Jr., Muriel Mirak-Weissbach, Antony Papert, Gerald Rose, Dennis Small, Edward Spannaus, Nancy EI R Spannaus, Jeffrey Steinberg, William Wertz Editor: Nancy Spannaus Managing Editor: Susan Welsh Assistant Managing Editor: Bonnie James Science Editor: Marjorie Mazel Hecht From the Managing Editor Technology Editor: Marsha Freeman Book Editor: Katherine Notley Photo Editor: Stuart Lewis Circulation Manager: Stanley Ezrol Who’s the guy on our cover? Some among our readers who are in INTELLIGENCE DIRECTORS need of new eyeglasses, may mistake him for Alan Greenspan—and Counterintelligence: Jeffrey Steinberg, Michele they wouldn’t be too far wrong. But this cayman is actually the CEO of Steinberg Economics: Marcia Merry Baker, Paul Gallagher a hedge fund in Queen Elizabeth’s Caribbean financial center, the Cay- History: Anton Chaitkin Ibero-America: Dennis Small man Islands. See John Hoefle’s chronicle (p. 15) for the gory details. Law: Edward Spannaus Our Feature documents how the U.S. home mortgage crisis is spin- Russia and Eastern Europe: Rachel Douglas ning so far out of control, that it threatens to bring down the global fi- United States: Debra Freeman nancial system any day—and yet, the U.S. Congress refuses to act. INTERNATIONAL BUREAUS With the Executive branch hijacked by Anglo-Dutch Liberalism, there Bogotá: Javier Almario Berlin: Rainer Apel is no other branch of government that can initiate effective action at this Copenhagen: Poul Rasmussen time.