The Origins of Hamas: Militant Legacy Or Israeli Tool?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pragmatic Dimension of the Palestinian Hamas: a Network Perspective

Mishal 569 The Pragmatic Dimension of the Palestinian Hamas: A Network Perspective SHAUL MISHAL n the wake of the 11 September attack on the World Trade Center in INew York and President Bush’s “war on terrorism,” it is important to try to understand the cultural, political, and social dimensions of such radical Islamic groups as the Palestinian Hamas. Within political and academic circles in the Western world, it is common to portray Islamic movements in categorical terms that utilize binary classifications that mark real or imaginary social attributes rather than relational patterns.1 Much of this perception derives from the violence accompanying Islamic reli- gious fervor and the fanaticism marking some of its groups and regimes, raising fears of “a clash of civilizations” and “a threat” to Western liberal democratic values and social order.2 Hamas, an abbreviation of Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya (Is- lamic Resistance Movement), did not escape the binary perception, and has been described solely as a movement identified with Islamic funda- mentalism and suicide bombings. The objectives at the top of its agenda are the liberation of Palestine through a holy war (jihad) against Israel, establishing an Islamic state on its soil, and reforming society in the spirit of true Islam. It is this Islamic vision, combined with its nationalist claims and militancy toward Israel, that accounts for the prevailing image of Hamas as a rigid movement, ready to pursue its goals at any cost, with no limits or constraints. Islamic and national zeal, bitter opposition to the SHAUL MISHAL teaches at the Department of Political Science at Tel Aviv University, where his research focuses on Arab and Palestinian politics. -

Political Expectations and Cultural Perceptions in the Arab-Israeli Peace Negotiations

Political Psychology, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2002 Political Expectations and Cultural Perceptions in the Arab-Israeli Peace Negotiations Shaul Mishal and Nadav Morag Department of Political Science Tel Aviv University In the various Arab-Israeli peace negotiations that have taken place since the late 1970s, each party entered the process, and continues to function within it, from the vantage point of different political expectations and cultural perceptions. These differences derive from the political features and social structures of the Arab parties and the Israeli side, which range from hierarchical to networked. Israel leans toward hierarchical order, whereas the Arab parties are more networked; these differences in the social and political environments influence the negotiating culture of each party. Hierarchical states develop goal-oriented negotiating cultures, whereas networked states have process-oriented negotiating cultures. The expectations that each side has of the other side to fulfill its part of the bargain are different as well; in hierarchical states such expectations are based on contracts, whereas in networked states such expectations are based on trust. Because it is unlikely that different cultural perceptions and the gap between the parties can be significantly bridged, it may be possible to cope with mutual problems if all parties were willing to accept a reality of perceptional pluralism (i.e., negotiating asymmetric arrangements, rather then each party insisting on mutual accommodation based on its own perspective). KEY WORDS: hierarchical states, networked states, goal-oriented negotiating cultures, process-oriented negotiating cultures, contract, trust, perceptional pluralism Much of the history of Arab-Israeli peace negotiations can be described in terms of mistrust and a lack of understanding by each side with respect to the psychological and political needs of the other. -

An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis

American University International Law Review Volume 15 | Issue 5 Article 2 2000 Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem Ardi Imseis Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Imseis, Ardi. "Facts on the Ground: An Examination of Israeli Municipal Policy in East Jerusalem." American University International Law Review 15, no. 5 (2000): 1039-1069. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACTS ON THE GROUND: AN EXAMINATION OF ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ARDI IMSEIS* INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1040 I. BACKGROUND ........................................... 1043 A. ISRAELI LAW, INTERNATIONAL LAW AND EAST JERUSALEM SINCE 1967 ................................. 1043 B. ISRAELI MUNICIPAL POLICY IN EAST JERUSALEM ......... 1047 II. FACTS ON THE GROUND: ISRAELI MUNICIPAL ACTIVITY IN EAST JERUSALEM ........................ 1049 A. EXPROPRIATION OF PALESTINIAN LAND .................. 1050 B. THE IMPOSITION OF JEWISH SETTLEMENTS ............... 1052 C. ZONING PALESTINIAN LANDS AS "GREEN AREAS"..... -

Gaza Emergency Daily Report – 31 August 2014

Gaza Emergency Daily Report – 31 August 2014 Transport Services Logistics Cluster transportation into the Gaza Strip since activation on 30 July 2014: Total Number of Trucks 184 Total Number of Pallets 4809 Total number Organizations Supported 37 Logistics Cluster transportation into the Gaza Strip – 31 August 2014: Final Number Number of Consignor From Consignee Sector Destination of pallets Trucks Shelter Global Communities Ramallah Gaza City CHF International 30 1 Food Ministry Of Social Ministry Of Social Shelter Ramallah Gaza City 140 5 Affairs (MoSA) Affairs (MoSA) Gaza WASH Agricultural Agricultural Food Development Development Ramallah Gaza City 52 Shelter 2 Association (PARC) Association (PARC) WASH Ramallah Gaza Union of Union of Agricultural Food Agricultural Work Work Committees Nablus Gaza City 31 Shelter 1 Committees (UAWC) WASH (UAWC) Food Hebron Food Trade Ministry Of Social Hebron Gaza City 56 Shelter 2 Association Affairs (MoSA) Gaza WASH Food Social Welfare Ministry Of Social Bethlehem Gaza City 23 Shelter 1 Committee Affairs (MoSA) Gaza WASH Private donation from Ministry Of Social Shelter Bethlehem Gaza City 14 Dar Salah Affairs (MoSA) Gaza Food Earth & Human Applied Research Center for Shelter Institute- Bethlehem Gaza City 2 1 researches and Food Jerusalem(ARIJ) studies (EHCRS) Social Welfare Ministry Of Social Shelter Bethlehem Gaza City 10 Committee Affairs (MoSA) Gaza Food TOTAL 358 13 Coordination/ Information Management/ GIS The Logistics Cluster is compiling information and assessing partners’ needs to determine whether the Rafah crossing can be used on a more permanent basis to support the humanitarian community transport relief items from Egypt into the Gaza Strip. www.logcluster.org Gaza Emergency Daily Report – 31 August 2014 Logistics Gaps and Bottlenecks The Logistics Cluster continues to monitor the impact of the ceasefire on logistics access constraints and the security of humanitarian space for the transportation and distribution of relief supplies. -

Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence

Terrorism and Political Violence ISSN: 0954-6553 (Print) 1556-1836 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ftpv20 Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence Seung-Whan Choi & Benjamin Acosta To cite this article: Seung-Whan Choi & Benjamin Acosta (2018): Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence, Terrorism and Political Violence, DOI: 10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 Published online: 13 Jun 2018. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ftpv20 TERRORISM AND POLITICAL VIOLENCE https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2018.1472585 Sunni Suicide Attacks and Sectarian Violence Seung-Whan Choi c and Benjamin Acosta a,b aInterdisciplinary Center Herzliya, Herzliya, Israel; bInternational Institute for Counter-Terrorism, Herzliya, Israel; cPolitical Science, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA ABSTRACT KEY WORDS Although fundamentalist Sunni Muslims have committed more than Suicide attacks; sectarian 85% of all suicide attacks, empirical research has yet to examine how violence; Sunni militants; internal sectarian conflicts in the Islamic world have fueled the most jihad; internal conflict dangerous form of political violence. We contend that fundamentalist Sunni Muslims employ suicide attacks as a political tool in sectarian violence and this targeting dynamic marks a central facet of the phenomenon today. We conduct a large-n analysis, evaluating an original dataset of 6,224 suicide attacks during the period of 1980 through 2016. A series of logistic regression analyses at the incidence level shows that, ceteris paribus, sectarian violence between Sunni Muslims and non-Sunni Muslims emerges as a substantive, signifi- cant, and positive predictor of suicide attacks. -

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: the Most Important Events Yasser

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: The Most Important Events Yasser Arafat Foundation 1 Early 20th Century - The total population of Palestine is estimated at 600,000, including approximately 36,000 of the Jewish faith, most of whom immigrated to Palestine for purely religious reasons, the remainder Muslims and Christians, all living and praying side by side. 1901 - The Zionist Organization (later called the World Zionist Organization [WZO]) founded during the First Zionist Congress held in Basel Switzerland in 1897, establishes the “Jewish National Fund” for the purpose of purchasing land in Palestine. 1902 - Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II agrees to receives Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement and, despite Herzl’s offer to pay off the debt of the Empire, decisively rejects the idea of Zionist settlement in Palestine. - A majority of the delegates at The Fifth Zionist Congress view with favor the British offer to allocate part of the lands of Uganda for the settlement of Jews. However, the offer was rejected the following year. 2 1904 - A wave of Jewish immigrants, mainly from Russia and Poland, begins to arrive in Palestine, settling in agricultural areas. 1909 Jewish immigrants establish the city of “Tel Aviv” on the outskirts of Jaffa. 1914 - The First World War begins. - - The Jewish population in Palestine grows to 59,000, of a total population of 657,000. 1915- 1916 - In correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, and Sharif Hussein of Mecca, wherein Hussein demands the “independence of the Arab States”, specifying the boundaries of the territories within the Ottoman rule at the time, which clearly includes Palestine. -

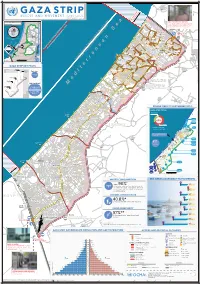

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

RESPONSES to INFORMATION REQUESTS (Rirs) Page 1 of 2

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIR's | Help 03 April 2006 JOR101125.E Jordan: The "Arab National Movement" and treatment of its members by authorities (January 1999 - March 2006) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa Information on the Arab National Movement (ANM) in Jordan was scarce among the sources consulted by the Research Directorate. The ANM is described as a Marxist political party (Political Handbook of the Middle East 2006 2006, 238) founded in Beirut in 1948 following the founding of the State of Israel (HRW Oct. 2002; CDI 23 Oct. 2002). The ANM was founded (IPS n.d.) and led by George Habash who went on to create the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PLFP) (ibid.; HRW Oct. 2002). According to the Center for Defense Information (CDI), a part of the World Security Institute (WSI), which is a research institute supported by public charity and based in Washington, DC (CDI n.d.), the ANM "spread quickly throughout the Arab World" (ibid. 23 Oct. 2002). The CDI added that the ANM was allied with Egypt's Gamal Abdul- Nasser, with whom it shared views on "a unified, free and socialist Arab world with an autonomous Palestine" (ibid.). The Political Handbook of the Middle East 2006 stated that in a 1989 Jordanian poll, the ANM was one of several political parties supporting independent political candidates (2006, 238). The most recent media report on the ANM found by the Research Directorate was from the 29 August 1999 issue of the Jerusalem-based Al-Quds newspaper, which reported that members of the ANM were part of a subcommittee to the Jordanian Opposition Parties' Coordinating Committee, made up of the 14 Jordanian opposition parties. -

Abu Al-Adib)” in Yakhluf, Yaḥyá

“Recording the History of the Palestinian Revolution: Testimony of Salim al-Za ͑nun (Abu Al-Adib)” in Yakhluf, Yaḥyá. Shahadāt ’n Tarikh al-Thawra al-Filastiniya. Ramallah: Sakher Habash Centre for Documentation and Intellectual Studies, 2010. Translated by The Palestinian Revolution.1 Recording the History of the Palestinian Revolution I want to go back to the year 1948. I’m a member of the generation that witnessed the defeat and saw the indifference that Arab regimes showed towards the catastrophe caused by the Zionist enemy. At that time I was a student in the last year of high school. When the battle started we were still not allowed to form student unions. The headmaster by orders from the British Mandate that ruled Palestine at that time didn’t allow any student activities in the school. However, we formed such unions in secret. We marched, despite the school’s headmaster, out of the school to Tal al-Menthar where the frontline with the Zionist enemy was. There, we participated with the Palestinian resistance fighters in digging trenches even though we were young at that time. The war ended. Arab states and Israel signed the first and then the second ceasefires. School resumed and we went back to studying. The political situation changed and now Egypt ruled the Gaza Strip. We became more able to be politically active than was possible during the British Mandate. I must mention one of the good things the Egyptian government did was opening the door of education for us. Instead of having the two top students in Gaza continuing their education in Rashidiya School in Jerusalem, everyone who passed high school was able to continue their education in Egypt. -

Hamas Attack on Israel Aims to Capitalize on Palestinian

Selected articles concerning Israel, published weekly by Suburban Orthodox Toras Chaim’s (Baltimore) Israel Action Committee Edited by Jerry Appelbaum ( [email protected] ) | Founding editor: Sheldon J. Berman Z”L Issue 8 8 7 Volume 2 1 , Number 1 9 Parshias Bamidbar | 48th Day Omer May 1 5 , 2021 Hamas Attack on Israel Aims to Capitalize on Palestinian Frustration By Dov Lieber and Felicia Schwartz wsj.com May 12, 2021 It is not that the police caused the uptick in violence, forces by Monday evening from Shei kh Jarrah. The but they certainly ran headfirst, full - speed, guns forces were there as part of security measures surrounding blazing into the trap that was set for them. the nightly protests. When the secretive military chief of the Palestinian As the deadline passed, the group sent the barrage of Islamist movement Hamas emerged from the shadows last rockets toward Jerusalem, precipitating the Israeli week, he chose to weigh in on a land dispute in East response. Jerusalem, threatening to retaliate against Israel if Israeli strikes and Hamas rocket fire have k illed 56 Palestinian residents there were evicted from their homes. Palestinians, including 14 children, and seven Israelis, “If the aggression against our people…doesn’ t stop including one child, according to Palestinian and Israeli immediately,” warned the commander, Mohammad Deif, officials. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Israel “the enemy will pay an expensive price.” has killed dozens of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad Hamas followed through on the threat, firing from the operatives. Gaza Strip, which it governs, over a thousand rockets at Althou gh the Palestinian youth have lacked a single Israel since Monday evening. -

The Legitimacy of the Modern Militia

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2001 The Legitimacy of the Modern Militia Jonathan Huber Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Huber, Jonathan, "The Legitimacy of the Modern Militia" (2001). Honors Theses. 134. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/134 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .. The Legitimacy of the Modem Militia Jonathan Huber Honors Thesis Ouachita Baptist University April 26, 2001 Introduction On May 16, 2001, barring any last minute court appeals, Timothy MeVeigh will be executed for his role in the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. He along with thousands of other Americans who have joined private armies, known as militia, to fight the American government share a common belief that the American government is corrupt at its core and actions such as this one are at the very least patriotic. To most Americans, however, acts such as the bombing of the Oklahoma City Federal Building are not only terroristic, but demonstrate the need for the American government to crack down on these type of organizations to prevent similar atrocities. Is there any justification for the existence of militia groups in the United States, even though most Americans deplore their actions and ideals? This paper will examine the historical use of the militia in the United States and its modem adaptation of militia heritage as well as several different types of militias and recent events that have helped this topic to emerge to the forefront of current discourse. -

BPA in Memoriam G. Habash 24 Feb 08

IN MEMORIAM GEORGE HABASH (1926 – 2008) Born in LYDDA, PALESTINE Died in Exile AMMAN, JORDAN “Every Palestinian has the right to fight for his home, his land, his family and his dignity – these are his rights.” George Habash, 1998 Dr George Habash was born into a Christian merchant family in Palestine and experienced the devastating effects of the Palestinian al-Nakba (Catastrophe) when he and his family along with 750,000 fellow Palestinians were terrorised into leaving their homes and homeland by Zionist forces to make way for the artificially created Jewish state, Israel. Although he graduated in medicine and specialised in paediatrics, he eventually devoted his time to the life-long struggle for the liberation of Palestine. In 1952, he founded the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM) which aimed to unify the Arab world to confront Israel. He saw Zionism as a force that would divide the Arab world and believed that Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser would be the instrument of Arab unity that would enable a conventional war to be mounted against Israel. The Arab loss of the 1967 six-day war dashed his hopes and the ANM folded. Habash then decided that guerrilla war was the only option for the Palestinians (despite his initial criticism of Arafat’s Fedayyeen) and he formed the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). He believed that desperate people must turn to desperate acts and although the hijacking of planes brought world-wide condemnation, it also brought publicity to the Palestinian cause. “When we hijack a plane it has more effect than if we killed a hundred Israelis in battle .