Palestinian Forces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Comparison of Bank Fraud

Journal of Cybersecurity, 3(2), 2017, 109–125 doi: 10.1093/cybsec/tyx011 Research paper Research paper International comparison of bank fraud reimbursement: customer perceptions and contractual terms Ingolf Becker,1,* Alice Hutchings,2 Ruba Abu-Salma,1 Ross Anderson,2 Nicholas Bohm,3 Steven J. Murdoch,1 M. Angela Sasse,1 and Gianluca Stringhini1 1Computer Science Department, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT; 2 University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory, 15 JJ Thomson Avenue, CB3 0FD; 3Foundation for Information Policy Research *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Received 7 May 2017; accepted 17 November 2017 Abstract The study presented in this article investigated to what extent bank customers understand the terms and conditions (T&Cs) they have signed up to. If many customers are not able to understand T&Cs and the behaviours they are expected to comply with, they risk not being compensated when their accounts are breached. An expert analysis of 30 bank contracts across 25 countries found that most contract terms were too vague for customers to infer required behaviour. In some cases the rules vary for different products, meaning the advice can be contradictory at worst. While many banks allow customers to write Personal identification numbers (PINs) down (as long as they are disguised and not kept with the card), 20% of banks categorically forbid writing PINs down, and a handful stipulate that the customer have a unique PIN for each account. We tested our findings in a survey with 151 participants in Germany, the USA and UK. They mostly agree: only 35% fully understand the T&Cs, and 28% find important sections are unclear. -

OBITUARIES Picked up at a Comer in New York City

SUMMER 2004 - THE AVI NEWSLETTER OBITUARIES picked up at a comer in New York City. gev until his jeep was blown up on a land He was then taken to a camp in upper New mine and his injuries forced him to return York State for training. home one week before the final truce. He returned with a personal letter nom Lou After the training, he sailed to Harris to Teddy Kollek commending him Marseilles and was put into a DP camp on his service. and told to pretend to be mute-since he spoke no language other than English. Back in Brooklyn Al worked While there he helped equip the Italian several jobs until he decided to move to fishing boat that was to take them to Is- Texas in 1953. Before going there he took rael. They left in the dead of night from Le time for a vacation in Miami Beach. This Havre with 150 DPs and a small crew. The latter decision was to determine the rest of passengers were carried on shelves, just his life. It was in Miami Beach that he met as we many years later saw reproduced in his wife--to-be, Betty. After a whirlwind the Museum of Clandestine Immigration courtship they were married and decided in Haifa. Al was the cook. On the way out to raise their family in Miami. He went the boat hit something that caused a hole into the uniform rental business, eventu- Al Wank, in the ship which necessitated bailing wa- ally owning his own business, BonMark Israel Navy and Palmach ter the entire trip. -

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

Israel, Palestine, and the Olso Accords

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 23, Issue 1 1999 Article 4 Israel, Palestine, and the Olso Accords JillAllison Weiner∗ ∗ Copyright c 1999 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Israel, Palestine, and the Olso Accords JillAllison Weiner Abstract This Comment addresses the Middle East peace process, focusing upon the relationship be- tween Israel and Palestine. Part I discusses the background of the land that today comprises the State of Israel and its territories. This Part summarizes the various accords and peace treaties signed by Israel, the Palestinians, and the other surrounding Arab Nations. Part II reviews com- mentary regarding peace in the Middle East by those who believe Israel needs to surrender more land and by those who feel that Palestine already has received too much. Part II examines the conflict over the permanent status negotiations, such as the status of the territories. Part III argues that all the parties need to abide by the conditions and goals set forth in the Oslo Accords before they can realistically begin the permanent status negotiations. Finally, this Comment concludes that in order to achieve peace, both sides will need to compromise, with Israel allowing an inde- pendent Palestinian State and Palestine amending its charter and ending the call for the destruction of Israel, though the circumstances do not bode well for peace in the Middle East. ISRAEL, PALESTINE, AND THE OSLO ACCORDS fillAllison Weiner* INTRODUCTION Israel's' history has always been marked by a juxtaposition between two peoples-the Israelis and the Palestinians 2-each believing that the land is rightfully theirs according to their reli- gion' and history.4 In 1897, Theodore Herzl5 wrote DerJeden- * J.D. -

Using a Civil Suit to Punish/Deter Sponsors of Terrorism: Connecting Arafat & the PLO to the Terror Attacks in the Second In

Digital Commons at St. Mary's University Faculty Articles School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2014 Using a Civil Suit to Punish/Deter Sponsors of Terrorism: Connecting Arafat & the PLO to the Terror Attacks in the Second Intifada Jeffrey F. Addicott St. Mary's University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.stmarytx.edu/facarticles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey F. Addicott, Using a Civil Suit to Punish/Deter Sponsors of Terrorism: Connecting Arafat & the PLO to the Terror Attacks in the Second Intifada, 4 St. John’s J. Int’l & Comp. L. 71 (2014). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Articles by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at St. Mary's University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USING A CIVIL SUIT TO PUNISH/DETER SPONSORS OF TERRORISM: CONNECTING ARAFAT & THE PLO TO THE TERROR ATTACKS IN THE SECOND INTIFADA Dr. Jeffery Addicott* INTRODUCTION “All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing.”1 -Edmund Burke As the so-called “War on Terror” 2 continues, it is imperative that civilized nations employ every possible avenue under the rule of law to punish and deter those governments and States that choose to engage in or provide support to terrorism.3 *∗Professor of Law and Director, Center for Terrorism Law, St. Mary’s University School of Law. -

When Are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel's Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-Examined

This is a repository copy of When are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel's Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-examined. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/79021/ Version: WRRO with coversheet Article: Arielli, N (2014) When are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel's Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-examined. Journal of Military History, 78 (2). pp. 703-724. ISSN 0899- 3718 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/79021/ Paper: Arielli, N (2014) When are foreign volunteers useful? Israel's transnational soldiers in the war of 1948 re-examined. Journal of Military History, 78 (2). 703 - 724. White Rose Research Online [email protected] When are Foreign Volunteers Useful? Israel’s Transnational Soldiers in the War of 1948 Re-examined Nir Arielli Abstract The literature on foreign, or “transnational,” war volunteering has fo- cused overwhelmingly on the motivations and experiences of the vol- unteers. -

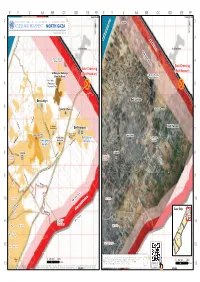

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

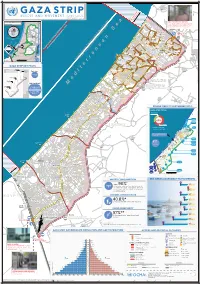

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

The Arab-Israeli Conflict and Civil Litigation Against Terrorism

SCHUPACK IN FINAL 9/8/2010 11:38:51 AM THE ARAB-ISRAELI CONFLICT AND CIVIL LITIGATION AGAINST TERRORISM ADAM N. SCHUPACK† ABSTRACT The Arab-Israeli conflict has been a testing ground for the involvement of U.S. courts in foreign conflicts and for the concept of civil litigation against terrorists. Plaintiffs on both sides of the dispute have sought to recover damages in U.S. courts, embroiling the courts in one of the world’s most contentious political disputes. Plaintiffs bringing claims against the Palestine Liberation Organization, the Palestinian Authority, material supporters of terrorism, and the Islamic Republic of Iran have been aided by congressional statutes passed precisely to enhance their ability to bring such lawsuits, whereas plaintiffs bringing suit against Israel or Israeli leaders have not had the benefit of such laws. Although the courts have sought to give effect to the congressional authorization embodied in these statutes, they have faced the resistance—at times half-hearted—of the executive branch, which regards such legislative and judicial involvement as an intrusion on its foreign policy prerogatives. Though these lawsuits have been subject to criticism and have not fully achieved the goals attributed to them, U.S. courts have largely acted within the authority given them by Congress and the executive branch in hearing the suits, and there is at least some evidence that such lawsuits constitute an effective tool in the fight against terrorism. INTRODUCTION Alisa Flatow, a twenty-year-old Brandeis University student studying in Israel, was killed on April 9, 1995, when Palestinian Copyright © 2010 Adam N. -

1987-1993 — the Intifada: the Palestinian Resistance Mo(Ve)Ment ————————— 7

————————— 1987-1993 — The Intifada: The Palestinian Resistance Mo(ve)ment ————————— 7. 1987-1993 — The Intifada: The Palestinian Resistance Mo(ve)ment1 I. Introduction The Israeli polity saw two major structural changes during the post- colonial era: the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 and the insti- tutionalization of the dual democratic/ military regime after 1967. Despite these two tremendous transformations in terms of popula- tion, economy, territory and bureaucracies, the colonial Zionist Labor Movement (ZLM) proved strong enough to maintain its institutional structure and power. The only long-term political development occurred gradually, with the transition from a monopoly of a single ruling party to a bipartisan “left/right cartel” (see Chapter 5) made up of two Zion- ist party blocks. Although these two blocks competed for power, tribal channeling of polarized hostile feelings closed political space to new actors, while in fact both implemented similar economic policies and supported the dual regime (Ben Porath, 1982; Grinberg, 1991, 2010). The ruling Labor Alignment, in cooperation with the Histadrut and the security establishment, institutionalized the dual regime designed to maintain control of the economy and population on both sides of the Green Line separating sovereign Israel from the Occupied Territories. The Labor Movement ideology, however, was unequipped to legitimize the military occupation or reassert the state’s institutional autonomy after 1967. The Likud government elected for the first time in 1977 was able to legitimize the occupation but unable to control the economy due to the lack of state autonomy and its incapacity to articulate economic interests, which became its most critical obstacle (see Chapter 6). -

Palestinian Nonviolent Resistance to Occupation Since 1967

FACES OF HOPE A Campaign Supporting Nonviolent Resistance and Refusal in Israel and Palestine AFSC Middle East Resource series Middle East Task Force | Fall 2005 Palestinian Nonviolent Resistance to Occupation Since 1967 alestinian nonviolent resistance to policies of occupa- tion and injustice dates back to the Ottoman (1600s- P1917) and British Mandate (1917-1948) periods. While the story of armed Palestinian resistance is known, the equally important history of nonviolent resistance is largely untold. Perhaps the best-known example of nonviolent resistance during the mandate period, when the British exercised colo- nial control over historic Palestine, is the General Strike of 1936. Called to protest against British colonial policies and the exclusion of local peoples from the governing process, the strike lasted six months, making it the longest general strike in modern history. Maintaining the strike for so many months required great cooperation and planning at the local Residents of Abu Ghosh, a village west of Jerusalem, taking the oath level. It also involved the setting up of alternative institu- of allegiance to the Arab Higher Committee, April 1936. Photo: Before tions by Palestinians to provide for economic and municipal Their Diaspora, Institute for Palestine Studies, 1984. Available at http://www. passia.org/. needs. The strike, and the actions surrounding it, ultimately encountered the dilemma that has subsequently been faced again and to invent new strategies of resistance. by many Palestinian nonviolent resistance movements: it was brutally suppressed by the British authorities, and many of The 1967 War the leaders of the strike were ultimately killed, imprisoned, During the 1967 War, Israel occupied the West Bank, or exiled. -

Northern Stage Presents the Winner of the 2017 Tony Award for Best Play

NORTHERN STAGE PRESENTS THE WINNER OF THE 2017 TONY AWARD FOR BEST PLAY ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT J.T. Rogers is a multiple award-winning, internationally recognized American playwright who lives in New York. His plays include Oslo, Blood and Gifts, The Overwhelming, White People, and Madagascar. In May 2017, Rogers won the Lucille Lortel Award for Best Play, the Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding New Broadway Play, and the 2017 Drama League Award for Outstanding Production of a Play, all for Oslo. Oslo was nominated for seven 2017 Tony Awards, including Best Play, as well as two 2017 Drama Desk Awards, including Outstanding Play. It ultimately won the Tony Award for Best Play and the Drama Desk Award for Outstanding Play. In 2017, Oslo also won the Obie Award for Best New American Theatre Work. “As a playwright, I look to tell stories that are framed against great political rupture. I am obsessed with putting characters onstage who struggle with, and against, cascading world events — and who are changed forever through that struggle. While journalism sharpens our minds, the theater can expand our sense of what it means to be human. It is where we can come together in a communal space to hear ideas that grip us, surprise us — even infuriate us — as we learn of things we didn’t know. For me, that is a deeply, thrillingly, political act.” TERMS TO KNOW ● PLO: Palestine Liberation Organization. The PLO represents the world’s Palestinians (Arabs who lived in Palestine before the 1948 establishment of the State of Israel).