Study on Small-Scale Agriculture in the Palestinian Territories Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Practices of Irrigation Water Pricing

\J4S ILI(QQ POLICY RESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Public Disclosure Authorized Efficiency and Equity Pricing of water may affect allocation considerations by Considerations in Pricing users. Efficiency isattainable andAllocating Irrigation wheneverthe pricing method affectsthe demandfor Public Disclosure Authorized Water irrigation water. The extent to which water pricing methods can affect income Yacov Tsur redistributionis limited.To Ariel Dinar affect incomeinequality, a water pricing method must include certain forms of water quantity restrictions. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The WorldBank Agricultureand Natural ResourcesDepartment Agricultural Policies Division May 1995 POLICYRESEARCH WORKING PAPER 1460 Summary findings Economic efficiency has to do with how much wealth a inefficient allocation. But they are usually easier to given resource base can generate. Equity has to do with implement and administer and require less information. how that wealth is to be distributed in society. Economic The extent to which water pricing methods can effect efficiency gets far more attention, in part because equity income redistribution is limited, the authors conclude. considerations involve value judgments that vary from Disparities in farm income are mainly the result of person to person. factors such as farm size and location and soil quality, Tsur and Dinar examine both the efficiency and the but not water (or other input) prices. Pricing schemes equity of different methods of pricing irrigation water. that do not involve quantity quotas cannot be used in After describing water pricing practices in a number of policies aimed at affecting income inequality. countries, they evaluate their efficiency and equity. The results somewhat support the view that water In general they find that water use is most efficient prices should not be used to effect income redistribution when pricing affects the demand for water. -

CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project

CENTRE FOR EUROPEAN POLICY WORKING PAPER NO. 9 STUDIES JUNE 2003 Searching for Solutions THE NEW WALLS AND FENCES: CONSEQUENCES FOR ISRAEL AND PALESTINE GERSHON BASKIN WITH SHARON ROSENBERG This Working Paper is published by the CEPS Middle East and Euro-Med Project. The project addresses issues of policy and strategy of the European Union in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the wider issues of EU relations with the countries of the Barcelona Process and the Arab world. Participants in the project include independent experts from the region and the European Union, as well as a core team at CEPS in Brussels led by Michael Emerson and Nathalie Tocci. Support for the project is gratefully acknowledged from: • Compagnia di San Paolo, Torino • Department for International Development (DFID), London. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed are attributable only to the author in a personal capacity and not to any institution with which he is associated. ISBN 92-9079-436-4 Available for free downloading from the CEPS website (http://www.ceps.be) CEPS Middle East & Euro-Med Project Copyright 2003, CEPS Centre for European Policy Studies Place du Congrès 1 • B-1000 Brussels • Tel: (32.2) 229.39.11 • Fax: (32.2) 219.41.41 e-mail: [email protected] • website: http://www.ceps.be THE NEW WALLS AND FENCES – CONSEQUENCES FOR ISRAEL AND PALESTINE WORKING PAPER NO. 9 OF THE CEPS MIDDLE EAST & EURO-MED PROJECT * GERSHON BASKIN WITH ** SHARON ROSENBERG ABSTRACT ood fences make good neighbours’ wrote the poet Robert Frost. Israel and Palestine are certainly not good neighbours and the question that arises is will a ‘G fence between Israel and Palestine turn them into ‘good neighbours’. -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

The Absentee Property Law and Its Implementation in East Jerusalem a Legal Guide and Analysis

NORWEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCIL The Absentee Property Law and its Implementation in East Jerusalem A Legal Guide and Analysis May 2013 May 2013 Written by: Adv. Yotam Ben-Hillel Consulting legal advisor: Adv. Sami Ershied Language editor: Risa Zoll Hebrew-English translations: Al-Kilani Legal Translation, Training & Management Co. Cover photo: The Cliff Hotel, which was declared “absentee property”, and its owner Ali Ayad. (Photo by: Mohammad Haddad, 2013). This publication has been produced with the financial assistance of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position or the official opinion of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) is an independent, international humanitarian non-governmental organisation that provides assistance, protection and durable solutions to refugees and internally displaced persons worldwide. The author wishes to thank Adv. Talia Sasson, Adv. Daniel Seidmann and Adv. Raphael Shilhav for their insightful comments during the preparation of this study. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 8 2. Background on the Absentee Property Law .................................................. 9 3. Provisions of the Absentee Property Law .................................................... 14 3.1 Definitions .................................................................................................................... -

Nablus Salfit Tubas Tulkarem

Iktaba Al 'Attara Siris Jaba' (Jenin) Tulkarem Kafr Rumman Silat adh DhahrAl Fandaqumiya Tubas Kashda 'Izbat Abu Khameis 'Anabta Bizzariya Khirbet Yarza 'Izbat al Khilal Burqa (Nablus) Kafr al Labad Yasid Kafa El Far'a Camp Al Hafasa Beit Imrin Ramin Ras al Far'a 'Izbat Shufa Al Mas'udiya Nisf Jubeil Wadi al Far'a Tammun Sabastiya Shufa Ijnisinya Talluza Khirbet 'Atuf An Naqura Saffarin Beit Lid Al Badhan Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Kafr Sur Qusin Zawata Khirbet Tall al Ghar An Nassariya Beit Iba Shida wa Hamlan Kur 'Ein Beit el Ma Camp Beit Hasan Beit Wazan Ein Shibli Kafr ZibadKafr 'Abbush Al Juneid 'Azmut Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jit Sarra Salim Furush Beit Dajan Baqat al HatabHajja Tell 'Iraq Burin Balata Camp 'Izbat Abu Hamada Kafr Qallil Beit Dajan Al Funduq ImmatinFar'ata Rujeib Madama Burin Kafr Laqif Jinsafut Beit Furik 'Azzun 'Asira al Qibliya 'Awarta Yanun Wadi Qana 'Urif Khirbet Tana Kafr Thulth Huwwara Odala 'Einabus Ar Rajman Beita Zeita Jamma'in Ad Dawa Jafa an Nan Deir Istiya Jamma'in Sanniriya Qarawat Bani Hassan Aqraba Za'tara (Nablus) Osarin Kifl Haris Qira Biddya Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Talfit Qusra Salfit As Sawiya Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Bani Zeid 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Sinjil Turmus'ayya. -

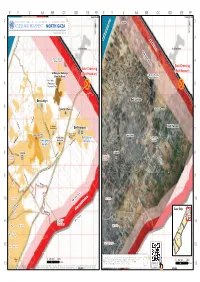

North Gaza ¥ August 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone

No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles 3 nautical miles X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF X Y Z AA BB CC DD EE FF Yad Mordekhai Yad Mordekhai 2 United Nations OfficeAs-Siafa for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs As-Siafa 2 ACCESS AND MOVEMENT - NORTH GAZA ¥ auGUST 2011 ¥ 3 3 Mediterranean Sea No-Go Zone Al-Rasheed Netiv ha-Asara Netiv ha-Asara High Risk Zone Temporary Wastewater 4 Treatment Lagoons 4 Erez Crossing Erez Crossing Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) (Beit Hanoun) Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) (Umm An-Naser) Beit Lahia 5 Wastewater 5 Treatment Plant Beit Lahiya Beit Lahiya 6 6 'Izbat Beit Hanoun 'Izbat Beit Hanoun Al Mathaf Hotel Al-Sekka Al Karama Al Karama El-Bahar Beit Lahia Main St. Arc-Med Hotel Al-Faloja Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Housing Project Beit Hanoun Madinat al 'Awda 7 v®Madinat al 'Awda 7 Beit Hanoun Jabalia Camp v® Industrial Jabalia Camp 'Arab Maslakh Zone Beit Hanoun 'Arab Maslakh Kamal Edwan Beit Lahya Beit Lahya Abu Ali Eyad Kamal Edwan Hospital Al-Naser Al-Saftawi Hospital Khalil Al-Wazeer Ahmad Sadeq Ash Shati' Camp Said El-Asi Jabalia Jabalia An Naser 8 Al-quds An Naser 8 El-Majadla Ash Sheikh Yousef El-Adama Ash Sheikh Al-Sekka Radwan Radwan Falastin Khalil El-Wazeer Al Deira Hotel Ameen El Husaini Heteen Salah El-Deen ! Al-Yarmook Saleh Dardona Abu Baker Al-Razy Palestine Stadium Al-Shifa Al-Jalaa 9 9 Hospital ! Al-quds Northern Rimal Al-Naffaq Al-Mashahra El-Karama Northern Rimal Omar El-Mokhtar Southern Rimal Al-Wehda Al-Shohada Al Azhar University Ad Daraj G Ad Daraj o v At Tuffah e At Tuffah 10 r 10 n High Risk Zone Islamic ! or Al-Qanal a University Yafa t e Haifa Jamal Abdel Naser Al-Sekka 500 meter NO-Go Zone Salah El-Deen Gaza Strip Beit Lahiya Al-Qahera Khalil Al-Wazeer J" Boundar J" y JabalyaJ" Al-Aqsa As Sabra Gaza City Beit Hanun Gaza City Marzouq GazaJ" City Northern Gaza Al-Dahshan Wire Fence Al 'Umari11 Wastewater 11 Mosque Moshtaha Treatment Plant Tal El Hawa Ijdeedeh Ijdeedeh Deir alJ" Balah Old City Bagdad Old City Rd No. -

500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM on the MOON a Documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES

500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES 500 DUNAM ON THE MOON a documentary by RACHEL LEAH JONES SYNOPSIS 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N is a documentary about the Palestinian village of Ayn Hawd which was captured and depopulated by Israeli forces in the 1948 war and subsequently transformed into a Jewish artist's colony and renamed Ein Hod. It tells the story of the village's original inhabitants who, after expulsion, settled only 1.5 kilometers away in the outlying hills. Since Israeli law prevents Palestinian refugees from returning to their homes, the refugees of Ayn Hawd established a new village: “Ayn Hawd al-Jadida” (The New Ayn Hawd). Ayn Hawd al-Jadida is an unrecognized village, which means that it receives no services such as electricity, water, or an access road. Relations between the artists and the refugees are complex: unlike most Israelis, the residents of Ein Hod know the Palestinians who lived there before them, since the latter have worked as hired hands for the former. Unlike most Palestinian refugees, the residents of Ayn Hawd al-Jadida know the Israelis who now occupy their homes, the art they produce, and the peculiar ways they try to deal with the fact that their society was created upon the ruins of another. It echoes the story of indigenous peoples everywhere: oppression, resistance, and the struggle to negotiate the scars of the past with the needs of the present and the hopes for the future. Addressing the universal issues of colonization, landlessness, housing rights, gentrification, and cultural appropriation in the specific context of Israel/Palestine, 500 DUNAM ON THE M00N documents the art of dispossession and the creativity of the dispossessed. -

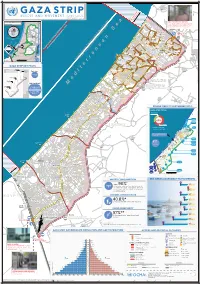

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Land Dispossession and Its Impact on Agriculture Sector and Food Sovereignty in Palestine: a New Perspective on Land Day

Land dispossession and its impact on agriculture sector and food sovereignty in Palestine: a new perspective on Land Day Inès Abdel Razek-Faoder and Muna Dajani On 30 March 1976, 37 years ago, in response to the Israeli government's announcement of a plan to expropriate thousands of dunams1 of land for "security and settlement purposes" on the lands of Galilee villages of Sakhnin and Arraba, Dair Hanna, Arab Alsawaed and other areas thousands of people took the street to protest, calling for a general strike as a peaceful mean to resisting colonization and government plans of judaization of the Galilee. Six Palestinians in Israel were killed. A month later the Koenig2 Memorandum was leaked to the press recommending, for “national interest”, “the possibility of diluting existing Arab population concentrations”. Land Day has been since then commemorated in all Palestine as a day of steadfastness and resistance. It became a symbol of the refusal of the Palestinians to leave their homeland, and to reject any form of ethnic cleansing and pressures for displacement. It is a day of attachment to freedom, on both sides of the Green Line and in all corners of the world. On this occasion, 37 years later, there is a necessity to highlight the consequences of this systematic illegal dispossession and control over the land and its natural resources on farming and agriculture. Farming has been fundamental in Palestinian identity and history, deeply rooted in the culture of land and of the struggle for freedom since the beginning of the 20th century. Predominantly an agricultural community, Palestine has been transformed from depending on its systems of self-sufficiency farming to the industrial chemical agriculture of today, all this under a brutal occupation depriving farmers of their land and water resources. -

Community Resilience Development

Annexes Annex 1: Evaluation Terms of Reference Annex 2: The Concept of Resilience Annex 3: Bibliography Annex 4: List of Documents Reviewed Annex 5: List of people met: interviewees, focus groups, field visits Annex 6: List of field visits Annex 7: Sample of Projects for Document Review Annex 8: Maps, Vulnerability and Resilience Data Annex 9: Analysis of CRDP Project Portfolio Profile Annex 10: Vulnerability Analysis Annex 11: Universal Lessons on Gender-Sensitive Resilience-Based programming Annex 12: Field Work Calendar Annex 13: Achievements of Programme (Rounds 1-3) 1 Annex 1: Evaluation Terms of Reference 1. BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT About the CRDP The Community Resilience Development Programme (CRDP) is the result of a fruitful cooperation between the Palestinian Government through the Ministry of Finance and Planning (MOFAP, the United Nations Development Programme/Programme of Assistance to the Palestinian People (UNDP/PAPP), and the Government of Sweden. In 2012, an agreement was signed between the Government of Sweden and UNDP/PAPP so as to support a three-year programme (from 2012 to 2016), with a total amount of SEK 90,000,000, equivalent to approximately USD 12,716,858. During the same year, the UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) joined the program and provided funds for the first year with an amount of £300,000, equivalent to USD 453,172. In 2013, the government of Austria joined the programme and deposited USD 4,202,585, (a final amount of approximately $557,414 remains to be deposited) to support the programme for two years. Finally, in 2014, the Government of Norway joined the programme with a contribution of USD 1,801,298 to support the programme for two years. -

Institute for Palestine Studies | Journals

Institute for Palestine Studies | Journals Journal of Palestine Studies issue 142, published in Winter 2007 16 August–15 November 2006 by 0 Chronology 16 August–15 November 2006 Compiled by Michele K. Esposito This section is part eighty-four of a chronology begun in JPS 13, no. 3 (Spring 1984). Chronology dates reflect Eastern Standard Time (EST). For a more comprehensive overview of events related to the al-Aqsa intifada and of regional and international developments related to the peace process, see the Quarterly Update on Conflict and Diplomacy in this issue. 16 AUGUST As the quarter opens, Israel’s blockade of Gaza enters its 6th mo., allowing no goods or people out (except for very limited medical emergencies) and letting only limited food and fuel supplies and a handful of diplomats and international aid workers in; Palestinians are receiving on average 6–8 hrs./day of electricity and 2–3 hrs./day of water after Israel’s bombing of Gaza’s sole generator on 6/28. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) continues Operation Summer Rains (see Quarterly Update in JPS 141), which began on 6/28 after the capture of an IDF soldier in a Palestinian cross-border raid fr. Gaza on 6/25, making occasional ground incursions into Gaza, maintaining troops at the Dahaniyya airport site outside of Rafah. In Gaza, the IDF launches air strikes, destroying a empty Palestinian home in Gaza City, causing no injuries; sends at least 50 armored vehicles into the outskirts of Bayt Hanun, firing on residential areas, bulldozing large areas of agricultural land, ordering residents of 15 houses to surrender for ID checks, arresting 2 before withdrawing across the border. -

Statistical Handbook of Middle Eastern Countries, Palestine, Cyprus, Egypt

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/statisticalhandbOOjewi JEWISH AGENCY FOR PAI^ESTINE ECONOMIC RESEARCH INSTITUTE STATISTICAL HANDBOOK OF MIDDLE EASTERN COUNTRIES PALESTINE, CYPRUS, EGYPT, IRAQ, THE LEBANON, SYRIA, TRANSJORDAN, TURKEY JERUSALEM, 1945 DISTRIBUTOR: D. B. AARONSON, P. O. B. 1175, JERUSALEM FOREWORD TO SECOND EDITION. This Handbook went out of print shortly after its first appearance, and a second edition was decided upon in response to numerous requests. In addition to the correction of certain misprints, the present issue includes an outline table as well as a supplement contaming new figures which have meanwhile become available. These additional statistics have been given the same serial numbers as the corresponding tables in the main text. The footnote signs are likewise those of the main tables. Suggestions for improvements or amendments to be included in any later edition will be appreciated. Jerusalem, April 1945. A. B. Copyright 1 944 by ihe Economic Research Institute of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, Jerusalem. Reprinted (with additions), 1945. Printed in Palestine by Stereotypes at tbe Azriel Printing Works, Jerusalem. -' PREFACE. -5 Modern economic policy has become almost entirely dependent on re- liable information regarding the processes and tendencies of economic and social life, which has been reduced to numerical statements and relationships. The growing complexity of modern society, the close connections to be found between the priyate and public fields of economy, the degree to which Government finance is dependent on foreign trade, employment, price level and other indices of economic development — all these make it necessary for the figures and data of economic and social life to be constantly available if state and political activities are to be successfully conducted nowadays.